Bengal District Gazetteers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asa

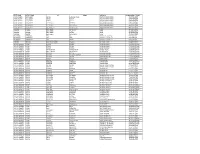

Branch Br.Name Code Address Contact No. 1 Dumka Marwarichowk ,Po- dumka,Dist - Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asanbani,Dist-Dumka, Pin-816123 VIA 7033293514 3 MAHESHPUR At+Po-Maheshpur Raj, Dist-Pakur,Pin-816106 7070896401 4 JAMA At+Po-Jama,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814162 7033293527 5 SHIKARIPARA At+Po-Shikaripara,Dist-Dumka,Pin 816118 7033293540 6 HARIPUR At+Po-Haripur,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814118 7033293526 7 PAKURIA At+Po-Pakuria,Dist-Pakur,Pin816117 7070896402 8 RAMGARH At+Po-Ramgarh,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814102 7033293536 9 HIRANPUR At+Po-Hiranpur,Dist-Pakur,Pin-816104 7070896403 10 KOTALPOKHAR PO-KOTALPOKHR, VIA- SBJ,DIST-SBJ,PIN- 816105 7070896382 11 RAJABHITA At+Po-Hansdiha] Dist-Godda] Pin-814101 7033293556 12 SAROUNI At+Po-Sarouni] Dist-Godda] Pin-814156 7033293557 13 HANSDIHA At+Po-Hansdiha,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293525 14 GHORMARA At+Po-Ghormara, Dist-Deoghar, Pin - 814120 7033293834 15 UDHWA At+Po-udhwa,Dist-Sahibganj pin-816108 7070896383 16 KHAGA At-Khaga,Po-sarsa,via-palajorihat,Pin-814146 7033293837 17 GANDHIGRAM At+Po-Gandhigram] Dist-Godda] Pin-814133 7033293558 18 PATHROLE At+po-pathrol,dist-deoghar,pin-815353 7033293830 19 FATHEPUR At+po-fatehpur,dist-Jamtara,pin-814166 7033293491 20 BALBADDA At+Po-Balbadda]Dist-Godda] Pin-813206 7033293559 21 BHAGAIYAMARI PO-SAKRIGALIGHAT,VIA-SBJ,PIN-816115 7070896384 22 MAHADEOGANJ PO-MAHADEVGANJ,VIA-SBJ,816109 7070896385 23 BANJHIBAZAR PO-SBJ AT JIRWABARI,816109 7070896386 24 DALAHI At-Dalahi,Po-Kendghata,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293519 25 PANCHKATHIA PO-PANCHKATIA,VIA BERHATE,816102 -

Bihar Military Police (BMP

FORM 1 (I) Basic Information Sl.No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s-Bihar Military Police (B.M.P- Bihar Govt. Project 12)Supaul 2. S.No. in the schedule 3. Proposed capacity /area/length/tonnage to be Plot area=283382 sq.m handled/command area/lease area/number of wells to be TotalBuilt up drilled. area=31190.65sq.m 4. New/Expansion/Modernization NEW 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. NIL 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ B 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, please specify. NO 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, please specify. YES 9. Location - Supaul Thana no.-1 Plot/Survey/Khasra No. Khata no.-339 Village - Birpur Kesra no.-1020 Tehsil- BASHAANTPUR District SUPAUL,MAUJA-BHIMNAGAR State - BIHAR 10. Nearest railway station/airport along with distance in kms. 32kmRadhupur ( railway station) 11. Nearest Town, city, district Headquarters along with 62 km. Supaul Head Quarter distance in kms. 12. Village Panchayats, Zilla Parishad, Municipal Corporation, Birpur,Bhimnagar. Local body (complete postal addresses with telephone nos. supaul to be given) 13. Name of the applicant Dhananjay kumar (Senior Architect) 14. Registered Address Kautaliya nagar patna -14 15. Address for correspondence: Bihar police Building Name cconstruction corporation Designation (Owner/Partner /CEO) Sunil kumar. Pin code ADG CUM CMD E-mail 800014 Telephone No. [email protected] Fax No. 0612-2224529 0612-2224529 16. Details of Alternative Sites examined, if any. Location of Village-District-State these sites should be shown on a topo sheet. 1 NIL 2 3 17. -

Disaster Management of India

DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN INDIA DISASTER MANAGEMENT 2011 This book has been prepared under the GoI-UNDP Disaster Risk Reduction Programme (2009-2012) DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN INDIA Ministry of Home Affairs Government of India c Disaster Management in India e ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The perception about disaster and its management has undergone a change following the enactment of the Disaster Management Act, 2005. The definition of disaster is now all encompassing, which includes not only the events emanating from natural and man-made causes, but even those events which are caused by accident or negligence. There was a long felt need to capture information about all such events occurring across the sectors and efforts made to mitigate them in the country and to collate them at one place in a global perspective. This book has been an effort towards realising this thought. This book in the present format is the outcome of the in-house compilation and analysis of information relating to disasters and their management gathered from different sources (domestic as well as the UN and other such agencies). All the three Directors in the Disaster Management Division, namely Shri J.P. Misra, Shri Dev Kumar and Shri Sanjay Agarwal have contributed inputs to this Book relating to their sectors. Support extended by Prof. Santosh Kumar, Shri R.K. Mall, former faculty and Shri Arun Sahdeo from NIDM have been very valuable in preparing an overview of the book. This book would have been impossible without the active support, suggestions and inputs of Dr. J. Radhakrishnan, Assistant Country Director (DM Unit), UNDP, New Delhi and the members of the UNDP Disaster Management Team including Shri Arvind Sinha, Consultant, UNDP. -

Adani Power (Jharkhand) Ltd

Intake Water System Detailed 2X800MW Thermal Power Plant, Godda , Jharkhand Project Project Proponent Adani Power (Jharkhand) Ltd. Report A Detail Project Report on Proposed Water Pipeline Route of 1600 (2 x 800) MW GODDA THERMAL POWER PROJECT GODDA, JHARKHAND ADANI POWER (JHARKHAND) LTD. Village - Motia, Tehsil Godda, District Godda, Jharkhand 1 Intake Water System Detailed 2X800MW Thermal Power Plant, Godda , Jharkhand Project Project Proponent Adani Power (Jharkhand) Ltd. Report Contents 1. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................ 3 1.1 Company Profile ............................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT BACKGOROUND / REQUIREMENT ............................................... 4 3. LOCATION MAP & KEY PLAN ......................................................................... 5 3.1 Jharkhand State Map ........................................................................................... 5 3.2 Godda Districts ..................................................................................................... 5 3.3 Project Site Water Intake location ................................................................ 6 3.4 Proposed Water Pipe Line Route ...................................................................... 6 4. KEY FEATURES OF THE PROJECT SITE ........................................................ 7 4.1 Site Location Details: .......................................................................................... -

STATE NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact Number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA

STATE_NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Nemam DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Panduru Panduru DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Minorpeta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Parrakalva DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Suryarao Peta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Thimmapuram Thimmapuram DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek GADHI BESHAK asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLA PAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek RAGA MAJRA asif ali 9991586053 EBT JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA Opa Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA JARIO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA ROCHO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI Badhra KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI GOPI(35) KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON SEEGON ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON HANDIA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON DHEDIYA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT RAMTEK RAIYAT JAGDISH KALME 8120828495 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT -

Cold Chain Handler

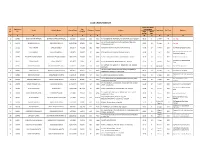

COLD CHAIN HANDLER Educational Quali. Sl. Application Age Intermediate Name Father's Name Date of Birth Category Gender Address Experience Resi. Cert. Remarks No. No. (Y/M/D) %age Marks Marks Obt. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1 164145 BIMBIT KUMAR MANDAL BHAWESH CHANDRA MANDAL 3/2/1967 51/11/3 BC1 Male AT- CHORBAD PO- AGIAMORE PS- POREYAHAT DIST- GODDA 45.78 0 1 Years NA Over Age VILL-MADANCHOKI,PO-DAVANCHAK,PS-MAHERMA,DIS- 2 163273 SHRAWAN MAHTO MAHANDRA MAHTO 25/09/1968 50/4/11 BC2 Male 50.22 10 2 Years NA Over Age GODDA,PIN-814160 3 164155 RAJIV RANJAN SARGUN DARBEY 8/8/1974 44/5/28 BC1 Male AT-KURMICHAK PO-KURMICHAK PS-GODDA M 54.00 10 2 Years SDO Old Resedential attached(2003) Experince Not Attached with Old 4 162847 LILA MIRDHA MAHADEV MIRDHA 1/9/1974 45/0/27 SC Male AT PARGODIH PO SUSNI PS DEODANR GODDA 41.89 0 NA SDO Resedential attached 5 163992 PRADEEP KUMAR MANDAL MAHENDRA PRASAD MANDAL 19/01/1975 44/0/17 BC1 Male AT+ PO- SAROUNI BAZAR,PS- GODDA(M),DIST-GODDA 58.33 10 1 Years SDO Old Resedential attached Experince From Rainbow Child 6 163011 SHYAM SAGAR YUGAL RAVIDAS 8/3/1975 43/6/2 SC Male AT+PO-BHANJPUR,PS-MAHAGAMA,DIST.- GODDA 62.00 10 2 Years SDO Clinic AT- LOCHANI PO- SANOUR PS- BASANTRAI DIST- GODDA 7 163442 MD NAYEEMUDDIN MD ABDUL MAJEED ALAM 1/20/1977 42/0/16 UR Male 60.00 10 11 Month SDO Experince Not Qualified jharkhand HATIYA CHOWK GODDA,NEAR OBC BANK,PO-GODDA,PS- 8 164141 PANKAJ YADAV SRI GULABI PRASAD YADAV 4/9/1977 41/9/27 BC2 Male 68.20 15 1 Years NA Resedential not attached GODDA,DIST-GODDA,ST-JHARKHAND Experince From Dr. -

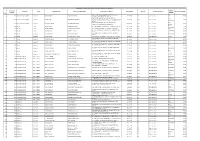

S .No. Application Number Panchayat Block Candidate Name Father's

Madhubani District-Revised List of Shortlisted Candidates of Uddeepika Application DD/IPO Panchayat Block Candidate Name Father's/ Husband Name Correspondence Address Date Of Birth Ctageory Permanent Address Percentage Of Marks Number Number S .No. PANCHAYAT-DAHIBAT MADHOPUR WEST, VILL+PO- 4906 Ahiwat Madhopur(West) Pandaul BIBHA KUMARI KAILASH PASWAN 13-Feb-86 SC Same as above 00 46.00 1 SALEMPUR, PS-PANDAUL, PIN-847234 PANCHAYAT-DAHIBHAT MADHOPUR WEST, VILL- 71G 3496 Ahiwat Madhopur(West) Pandaul MANJU DEVI CHANDRAMOHAN RAY MADHEPURA, P.O- D NATHWAN, DIST- MADHUBANI, PIN- 15-Feb-89 GEN Same as above 61.00 916592-93 2 847234 PANCHAYAT-DAHIBHAT MADHEPUR WEST, VILL- 39H 4825 Ahiwat Madhopur(West) Pandaul SUCHITA KUMARI JITENDRA KUMAR RAY 01-Nov-84 GEN Same as above 59.00 3 MADHEPURA, P.S- PANDAUL, PIN- 847234 346021 80G 4882 Akahri Ladania PUNITA DEVI BISHNU KANT ROY VILL- JHITKIYAHI, P.O- AKHARI, P.S- LADNIYA, PIN- 847232 16-Aug-90 EBC Same as above 55.00 4 722702-01 5 4013 Akahri Ladania RINKEE KUMARI PRADEEP KUMAR SAHNI VILL-PARSAHI, PO-SIDHAP, PS-LADANIA, PIN-847232 03-Jun-89 EBC Same as above 39H 59.00 VILL+P.O- AKRAHI, VIA- LADHNIYA, P.S- LADHNIYA, PIN- 816 Akahri Ladania RITA KUMARI BHARAT LAL RAY 05-Mar-90 EBC Same as above 7H 195984 63.00 6 847232 VILL- KESHULI, PO- AKAUR, PS- BENIPATTI, PINCODE- 1926 Akaur Benipatti BHAWANI DEVI MITHILESH KAMAT 11-Jan-85 EBC Same as above 2H 115821 66.00 7 847230 8 1510 Akaur Benipatti KIRAN KUMARI NAWAAL KISHOR YADAV VILL- KESHULI, P.O- AKAUR, P.S- BENIPATTI, PIN- 847230 08-Jan-81 BC Same as -

Final Report- Community Participation of Embankment Surveillance

Volume-I FINAL REPORT Submitted to: Joint Director, Flood Management Improvement Support Centre Water Resources Department 2nd Floor, Jal Sansadhan Bhawan Anisabad, Patna-800002 Tel.: 91612-2256999, 91612-2254802 JPS Associates (P) Ltd. New Delhi Acknowledgement We at JPS take opportunity to thank all the officials at WRD namely Mr. Er Indu Bhusan Kumar, Chief Engineer (Planning and Monitoring) Mr. Narendra Prasad Mandal, Additional Project Director (BAPEPS), Official in BAPEPS namely Mr. Ravi Kumar Gupta, State Project Specialist (Environment), Officials at FMISC Mr. A.K.Samaiyar (Ex-Joint Director), Mr. Sitaram Agarwal (Ex-Joint Director), Er. Anil Kumar (Deputy Director I), Mr. Dilip Kumar Singh (Ex-Deputy Director), Mr. Nagan Prasad (Joint Director), Mr. Zakauallah (Asst.Director), Mr. Mukesh Mathur (GIS Expert) and Mr. Syed Niyaz Khurram (Web Master) for their able guidance and constant support to us in the conduct of the assignment in a smooth manner. We are also thankful to WRD field officials Mr. Prakash Das (Chief Engineer), Birpur Division, Mr. Vijender Kumar (Chief Engineer) Samastipur Division, Mr. Vijender Kumar (Executive Er. Birpur Division), Mr. Vinod Kumar (Executive Er. Nirmali Division) and Mr. Mithilesh Kumar (Executive Er.) Jhanjharpur Division and all the Asst. Engineers and the Junior Divisions of all the 11 Field Divisions for their constant support and hospitality to our team of experts and field staff during the conduct of assignment at the field level. Our thanks are also due to SRC members, Mr. Sachidanand Tiwari (Embankment Expert), and Mr. Santosh Kumar (Hydrologist), Mr. Bimalendu Kumar .Sinha, Flood Management Advisor (FMISC) and Mr. S.K. -

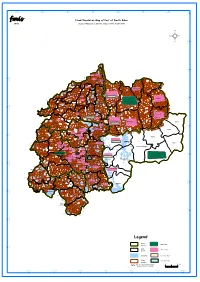

Full Page Fax Print

86°15'E 86°30'E 86°45'E 87°E 87°15'E 87°30'E 87°45'E 27°N fmis Flood Inundation Map of Part of North Bihar Bihar [Based on Radarsat-2 Satellite Image of 29th August 2008] ² 26°45'N 193 192 Lobiparas Banaili pattiBauraha Munshi piprahiGidarmari 191 26°30'N Baghi Birpur LalpurFatehpur Jhirw a 190 Bhimnagar 194 BasantpurGhauspurpatti Raniganj Barantpur Mohanpur 189 Dumri milikDubiahi Panchpanduria KataiaBhawanipurHedol wa 188 2 Dharhapatti az rakbe ch andip Samda Sitapur Lalpurgot 1 26°30'N Barhampur Piprahipatti golari BASANTPUR 87/1 85 4 3\1 Chhitauni Bishunpur chaudhary 195 187 87/2 86 84 3\2 26 Kunali Dharha Kamatpur 89/2 90 5 Bathnaha Kusahar 196 836 25 28 Bilandi Ratanpur 186 91 78 88 82 8 24 27 30/2 Kamalpur Dharhara Parsahi Basawanpatti RampurParwaha Nathpatti Parsa 181 178177 79 71 7 30/1 31 33 Harpur Balua 185 182 176 92 76 77 81 22 NIRMALI Repauli PiprahigotJagdispur Baisi Nirmali Nathbari197 198 199 184 179 73 709\2 22 29 32 Laukaha Gurdharia 183 175 93 72/1 69 38 37 35 34 Dagmara Gopalpur BaghiKarjain Shibnagar 203 200201 180169 174 75 10 16 Bahuarwa Undraha MatiariChainpur 204 173 159 119 94 74 72 /2 15 39 36 Uganipatti KorhaliChhithi hanuman nagar Gospur Thuthi205 218 167 168 160 120 118117 95 63 64 11 12\2 Sikti 21 40 Takia Parmanandpur Tengri 202 166 Kursakatta96 14 Sikrahata Simri Hariraha 206 165 162 156 121 115 97 62 65/166 67 68/1 175 13 18 20 41 Kabiahi FakirnaBaurahaSituhar Lachhminia Keola Bhimpur 208 217 174 17 19 42 43 Baisa 144 145 164 122 114 98 61 241 55 Dudhaila Siani Karhari Nonpara BerdahMotipurHarpur Gobindpur -

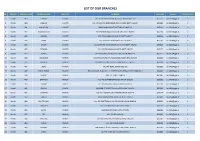

List of Our Branches

LIST OF OUR BRANCHES SR REGION BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME DISTRICT ADDRESS PIN CODE E-MAIL CONTACT NO 1 Ranchi 419 DORMA KHUNTI VILL+PO-DORMA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 2 Ranchi 420 JAMHAR KHUNTI VILL-JAMHAR,PO-GOBINDPUR RD,VIA-KARRA DISTT-KHUNTI. 835209 [email protected] 0 3 Ranchi 421 KHUNTI (R) KHUNTI MAIN ROAD,KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 210 835210 [email protected] 0 4 Ranchi 422 MARANGHADA KHUNTI VILL+PO-MARANGHADA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 5 Ranchi 423 MURHU KHUNTI VILL+PO-MURHU,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835216 [email protected] 0 6 Ranchi 424 SAIKO KHUNTI VILL+PO-SAIKO,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 7 Ranchi 425 SINDRI KHUNTI VILL-SINDRI,PO-KOCHASINDRI,VIA-TAMAR,DISTT-KHUNTI 835225 [email protected] 0 8 Ranchi 426 TAPKARA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TAPKARA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835227 [email protected] 0 9 Ranchi 427 TORPA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TORPA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 10 Ranchi 444 BALALONG RANCHI VILL+PO-DAHUTOLI PO-BALALONG,VIA-DHURWA RANCHI 834004 [email protected] 0 11 Ranchi 445 BARIATU RANCHI HOUSING COLONY, BARIATU, RANCHI P.O. - R.M.C.H., 834009 [email protected] 0 12 Ranchi 446 BERO RANCHI VILL+PO-BERO, RANCHI-825 202 825202 [email protected] 0 13 Ranchi 447 BIRSA CHOWK RANCHI HAWAI NAGAR, ROAD NO. - 1, KHUNTI ROAD, BIRSA CHOWK, RANCHI - 3 834003 [email protected] 0 14 Ranchi 448 BOREYA RANCHI BOREYA, KANKE, RANCHI 834006 [email protected] 0 15 Ranchi 449 BRAMBEY RANCHI VILL+PO-BRAMBEY(MANDER),RANCHI-835205 835205 [email protected] 0 16 Ranchi 450 BUNDU -

The Report of the Patna Iniversity Committee

CRITICISMS ON THE REPORT OF THE PATNA INIVERSITY COMMITTEE. T o D - t i < f |- 37S>-^STr-1sV'' i ' N l ^ C ¥ * l U - C . CRITICISMS ON THE REPORT OF THE PATNA UNIVEE SITY COMMITTEE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. P a g e Babu Badri Nath Upadhya, Korha, Pumea ... 1 Mr. P. Walfordj Principal, Bihar School of Engineering , 3 Rai Upendra Nath Ghosh, Bahadur, Deputy Collector in charge 6 of Orissa Canals, Revenue Division, iCuttack. Bihar Planters'Association ... ... ... 11 The National Society, Balasore ... ... 12 Mr. E. Schroder, Headmaster, Zila School, Bhagalpur , 13 Church Missionary Society, Calcutta ... ... , 16 Bihar Provincial Moslem League, Bankipore ... , 17 Ranchi Bihari Public ... ... ... 19 Bengali Settlers’ Association, Bhagalpur ... 20 Hon’ble Babu Bishun Prasad ... 22 Dr. Lakshmipati ... ... ... , 25 Mr. R. N . Gilchrist, Professor, Presidency College, Calcutta . 29 Mahamahopadhya Pandit Ganga Nath Jha 32 Hon’ble Maulvi Saiyid Muhammad Tahir ... 33 Edward Memorial Ayurvedic Pathshala, Aurangabad, Gaya , 36 Muhammadan Association, Bhagalpur ... ... 38 Moslem League, Bhagalpur ... ... • •• < 39 Patna Bar Association, Bankipore cat I 40 Fifth Bihar Provincial Conference ... ... 47, 63 Bengali Settlers' Association, Bihar and Orissa, Bankipore , 53 Commissioner, Bhagalpur Division ... ... 55 District Magistrate, Monghyr _ ' ' ^ ... 55 Commissioner, Patna Division ... 59 District Magistrate, Shahabad ... ... 59 Khan Sahib Saiyid Ahmad Ali Khan ••• I 60 Snbdivisional OfSoer, Buxar ... ... 61 Subdivisional Officer, Sasaram ... 61 District Magistrate, Gaya ... ... ... 61 Hon'ble Maharaja Sir Ravaneswar Praead Singh, Bahadnr, . 62 k .c.i j :.. of Gidhaur. Muhammadans of Chota Nagpur ,.l ... • 66 Commissioner, Orissa Division ... ... • 67 District Magistrate, Balasore ... ••• • 68, Pasgb District Magistrate, P’atna ... 71 Malthil Mahasabha, Darblianga 73, 86 Mr. S. Q. Huda ... ... 74 Calcutta Weekly Notes .. -

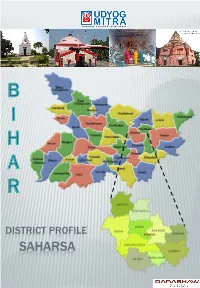

Saharsa Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE SAHARSA INTRODUCTION Saharsa is one of the thirty-eight districts of Bihar. Saharsa district became a separate district in 1954 prior to which it was a part of Kosi division. The important rivers flowing through the district are Kosi, Baghmati. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Earlier Saharsa district was within the Bhagalpur Division. Kosi Division was formed on 2nd October 1972 comprising of Saharsa, Purnia and Katihar district with its head quarters at Saharsa. Formerly it had no independent status and parts of Saharsa were included in the old districts of Munger & Bhagalpur. Ancient Times: In ancient times, Vaishali was the strongest republic in North-Bihar and beyond that lay the famous territory of Anguttarap. There was a small Janpad, named Apna, in Anguttarap and it included a portion of the district of Saharsa. Various sites of the district, now completely eroded and destroyed by the Kosi, viz. Biratpur, Budhiagarhi, Budhnaghat, Buddhadi, Pitahahi and Mathai are associated with Buddhism Both Anga and North Bihar (including Saharsa) continued to be independent till the early part of the sixth century B.C Between 320 and 1097 A.D Under the Guptas (from 320 A.D.), the entire North Bihar was consolidated as a Tirbhukti (province) with its capital at Vaishali. The extent of Saharsa during the period under review was upto the confines of Pundravardhanbhukti which included some of its present area. From the geographical point of view, Saharsa was the most strategically suited from being the Jayaskandharar (temporary Capital) of the Palas at the time when they were surrounded on all sides by enemies.