Occupational Health Risks and the Worker's Right to Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource Guide for Right to Know Training

A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR RIGHT TO KNOW TRAINING ~NEW~~~ IERSlY DEPARTMENT OF Division of Epidemiology, HIAI.lH Environmental and Occupational Health Services A BETIER STATE OF HEALTH Christine Todd Whitman Len Fishman Governor Commissioner of Health A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR RIGHT TO KNOW TRAINING Prepared by: Karen Miles, Ph.D., CHES Juanita Bynum, M.Ed., CHES William E. Parkin, D.V.M., Dr.P.H., Assistant Commissioner Division of Epidemiology, EnvironmenW and Occupational Health Services Kathleen O'Leary, M.S., Director Occupational Health Service Richard Willinger, J.D., M.P.H., Manager Right to Know Program JUNE 1994 ..A Resource Guide For Right to Know Training" was written by Karen Miles, Ph.D., CHES, former Coordinator of the Education and Outreach Project in the Right to Know Program, New Jersey Department of Health. This Guide was developed to assist public employees who conduct Right to Know education and training at their facility by providing background information on occupational health principles, the New Jersey Worker and Community Right to Know Act, and the Public Employees Occupational Safety and Health Act. The Resource Guide was edited by Juanita Bynum, M.Ed., CHES, Coordinator of the Education and Outreach Project of the Right to Know Program and Nancy Savage, Education and Outreach Project to reflect the August 2, 1993 and Januacy 3, 1994 amendments to the Right to Know regulations. Special thanks are extended to Richard Willinger, Program Manager, Right to Know Program, and Kathleen O'Leacy, Service Director, Occupational Health Service, who reviewed and edited the Guide, and to Eva McGovern and Cynthia McCoy for their assistance. -

Medical Ethics and Law (Questions and Answers) Prof. Mahmoud

EXAM QUESTIONS & ANSWERS LEGAL MEDICINE & MEDICAL ETHICs Prepared & Selected by Prof. Mahmoud Khraishi 1. You are a resident in the emergency department. An irate parent comes to you furious because the social worker has been asking him about striking his child. The child is a 5-year-old boy who has been in the emergency department four times this year with several episodes of trauma that did not seem related. Today, the child is brought in with a child complaint of “slipping into a hot bathtub” with a bum wound on his legs. The parent threatens to sue you and says “How dare you think that about me? I love my son!” What should you do? a. Admit the child to remove him from the possibly dangerous environment. b. Call the police. c. Ask the father yourself if there has been any abuse. d. Explain to the parents that the next time this happens you will have to call child protective services. e. Report the family to child protective services. Answer: (e) Report the family to child protective services. Comment: Although, in general, it is better to address issues directly with patients and their families, this is not the case when you strongly suspect child abuse. Reporting of child abuse is mandatory even based on suspicion alone. Although it is frightening to be confrontational with the family, the caregiver is legally protected even if there turns out to be no abuse as long as the report was made honestly and without malice. You do not have the authority to remove the child from the custody of the parents. -

Student Registration Information Training Forms to Be

First Name Last Name By placing my name here, I agree to be responsible for the content of this page. Your SSI Training Center will record your training progress. Upon successful completion of your SSI program, you will be issued an SSI certification that is internationally recognized and available anywhere with internet access. Your SSI Training Forms will be maintained at your registered SSI Training Center. If you change your SSI Training Center, then you will need to complete a new set of Training Forms. Student Registration Information First Name Last Name Date of Birth (DD/MM/YY) Mailing Address Email Address Phone Training Forms to be Completed ❏ Student Registration Student profile in MySSI created: Yes No Student Master ID (MID) _____________ Digital Kit(s) Issued: Yes No ❏ Privacy Policy Permanently valid. Needs to be completed once with each Training Center or if a formal request to have their personal information deleted from all SSI databases is submitted. ❏ Diver Medical Statement and Questionnaire Valid for 1 year. The addition of the Physician’s Approval Form is required if a “YES” is answered to any condition on the Diver Medical Questionnaire. If a student becomes Ill or Injured or has a significant medical condition change within 12 months that would conflict with their current Medical Statement & Questionnaire, they must complete a new form before continuing with any SSI training. ❏ Assumption of Risk/Liability Release (not to be used within the European Union) Valid for 1 year. The addition of the Youth Addendum Form is also required for all students under the age of 18 years old and it must be signed by a parent/guardian. -

Major League Baseball Players, Big Data, and the Right to Know

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 28 Article 9 Issue 1 Fall Major League Baseball Players, Big Data, and the Right to Know: The Duty of Major League Baseball Teams to Disclose Health Modeling Analysis to Their lP ayers Michael Hattery Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Privacy Law Commons Repository Citation Michael Hattery, Major League Baseball Players, Big Data, and the Right to Know: The Duty of Major League Baseball Teams to Disclose Health Modeling Analysis to Their Players, 28 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 257 (2017) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol28/iss1/9 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HATTERY 28.1 FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/9/18 11:39 AM COMMENTS MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PLAYERS, BIG DATA, AND THE RIGHT TO KNOW: THE DUTY OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL TEAMS TO DISCLOSE HEALTH MODELING ANALYSIS TO THEIR PLAYERS MICHAEL HATTERY* I. INTRODUCTION The big data frontier has brought with it nearly innumerable legal concerns, ranging from traditional privacy rights to messy and flawed data collection, as well as differing interests between those engaging in predictive modeling and those who are being used as data points.1 Major League Baseball teams are pioneers in the usage of big data, measuring players at a scale unseen in most other sectors of business.2 For Major League Baseball teams, players, and especially pitchers, are huge financial assets that come with significant risk of injury and depreciation. -

Patient and Visitor Guide Preparing for Your Stay

About NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital www.nyp.org NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, based in New York City, is one of the nation’s largest and most comprehensive hospitals, with some 2,600 beds. In 2013, there were more than 2 million inpatient and outpatient visits to the Hospital, including close to 15,000 deliveries and more than 310,000 emergency NewYork-Presbyterian department visits. Sloane Hospital for Women More than 6,500 affiliated physicians and 20,000 staff provide state-of-the-art inpatient, ambulatory, and preventive care in all areas of medicine at six campuses: Maternity Services NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian/Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, NewYork-Presbyterian/The Allen Hospital, NewYork-Presbyterian/Westchester Division, and NewYork-Presbyterian/Lower Manhattan Hospital. Patient and Visitor Guide NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital ranks consistently among the top hospitals in the nation, according to U.S. News & World Report. One of the most prestigious Preparing For Your Stay health care institutions in the world, the Hospital is committed to excellence in patient care, research, education, and community service. NewYork-Presbyterian has academic affiliations with two of the nation’s leading medical colleges: Weill Cornell Medical College and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. www.nyp.org (212) 305-5904 (212) Administration Services Patient (212) 305-3101 (212) Information Patient (212) 305-3270 (212) Records Medical (212) 305-5437 305-5437 (212) Information General (877) 843-2229 (877) Pediatrics Prenatal for Center (212) 305-3388 (212) Department Admitting Important Phone Numbers Phone Important Welcome Welcome to Sloane Hospital for Women, a special part of NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center. -

Patient Handbook

Patient Handbook Welcome to Redlands Community Hospital Redlands Community Hospital is committed to focus on our “Patient’s-First” philosophy, and only a insuring an optimal patient experience for both you few are mentioned in this guide. We ask that you take and your family. This booklet is filled with important a moment to read our Mission, Vision, and Values information to help make your experience with us found on page 23 as we go through great steps to both stress free and pleasant. implement them with every encounter we have with you and your family. If you have any concerns or Inside you will find information from how to order questions, please “Speak Up” and let us know so that meals to appointing someone to make medical we may immediately address them for you. decisions regarding your care. Here at Redlands Community Hospital we have many programs that Table of Contents Phone Numbers and Hospital Hours General Information: . 2-4 Main Hospital Number: • Social Services (909) 335-5500 • How To Identify Your Care Team Rapid Response Team: • Interpreter Services Dial 2000 • Pastoral Care Services and Chapel • Patient Experience Liaison To Place a Local Outside Call: • Billing Inquiries Dial 9, then the phone number . • Financial Assistance To Direct Dial a Patients Room: • Smoking Policy Dial (909) 335-5502 then enter the • Patient Password room number • Personal Belongings • Visitation Information Desk: • Our C .A R. .E . Channel 42 Extension 5545 • Our C .A R. .E . Channel 44 General Visiting Hours: • Free WiFi Service/Charging Stations Are Available 10 a .m . - 8 p .m . -

Patients' Rights to Access Their Medical Records: an Argument for Uniform Recognition of a Right of Access in the United States and Australia

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 21, Issue 4 1997 Article 7 Patients’ Rights to Access their Medical Records: An Argument for Uniform Recognition of a Right of Access in the United States and Australia Hayley Rosenman∗ ∗ Copyright c 1997 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Patients’ Rights to Access their Medical Records: An Argument for Uniform Recognition of a Right of Access in the United States and Australia Hayley Rosenman Abstract This Note addresses the issue of a patient’s right to access her own medical records in the United States and Australia. Part I discusses the background of a right of patient access to medical records through case law in the United States. Part I gives a historical perspective on US and Australian legislation regarding access to medical records. Part II reviews commentary both for and against access in the United States and in Australia. Part II focuses on legal arguments from the recent decision concerning patient access to medical records by the Australian courts in Breen v. Williams. Further, Part II also briefly examines jurisprudence with respect to access rights in Canada and the United Kingdom. Part III argues that the United States and Australia should follow the international trend and grant access to medical records through legislation. Finally, this Note concludes that a right of access would not only be fairer to patients and improve the physician- patient relationship, but also would facilitate transnational legal actions where medical records are required but the countries’ laws differ on the right of access. -

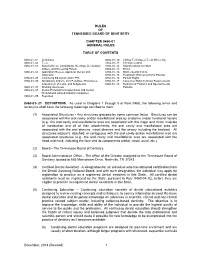

0460-01.20141229.Pdf

RULES OF TENNESSEE BOARD OF DENTISTRY CHAPTER 0460-01 GENERAL RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS 0460-01-.01 Definitions 0460-01-.10 Clinical Techniques-Teeth Whitening 0460-01-.02 Fees 0460-01-.11 Infection Control 0460-01-.03 Board Officers, Consultants, Meetings, Declaratory 0460-01-.12 Unprofessional Conduct Orders, and Screening Panels 0460-01-.13 Ethics 0460-01-.04 Application Review, Approval, Denial, and 0460-01-.14 Mobile Dental Clinics Interviews 0460-01-.15 Treatment of Nursing Home Patients 0460-01-.05 Continuing Education and C.P.R. 0460-01-.16 Patient Rights 0460-01-.06 Disciplinary Actions, Civil Penalties, Procedures, 0460-01-.17 Consumer Right-To-Know Requirements Assessment of Costs, and Subpoenas 0460-01-.18 Restraint of Pediatric and Special Needs 0460-01-.07 Working Interviews Patients 0460-01-.08 Dental Professional Corporations and Dental Professional Limited Liability Companies 0460-01-.09 Repealed 0460-01-.01 DEFINITIONS. As used in Chapters 1 through 5 of Rule 0460, the following terms and acronyms shall have the following meanings ascribed to them: (1) Associated Structures - Any structures grouped by some common factor. Structures can be associated with the oral cavity and/or maxillofacial area by anatomic and/or functional factors (e.g., the oral cavity and maxillofacial area are associated with the major and minor muscles of mastication and all of their attachments; the oral cavity and maxillofacial area are associated with the oral pharynx, nasal pharynx and the airway including the trachea). All structures adjacent, attached, or contiguous with the oral cavity and/or maxillofacial area are associated structures (e.g., the oral cavity and maxillofacial area are associated with the head and neck, including the face and its components orbital, nasal, aural, etc.). -

You Have the Right to Know

123456789 123456789 The following three agencies work together to imple- 123456789 123456789 123456789 123456789 ment the Worker and Community Right to Know Act: 123456789HOW TO OBTAIN INFORMATION LOCALLY New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services You can obtain copies of the Right to Know Survey, Right to Know Program YOU HAVE THE PO Box 368 Community Right to Know Survey, and Hazardous Trenton, NJ 08625-0368 Substance Fact Sheets from your designated Right to (609) 984-2202 Know county agency listed below: RIGHT TO www.state.nj.us/health/eoh/rtkweb Atlantic ................................. (609)645-5971 Ext. 4295 Enforces all provisions of the RTK Act in public work- Bergen................................. (201)634-2786 KNOW places and RTK labeling in private workplaces. The Burlington ............................ (609)265-5521 Ext. 5521 Program prepares Hazardous Substance Fact Sheets, Camden............................... (856)374-6046 the RTK brochure, and other materials to increase Cape May ............................ (609)463-6413 awareness of hazardous chemicals and help employ- Cumberland ........................ (856)453-2156 ers comply with the RTK Act. Printed materials are Essex ................................... (973)497-9401 available upon request. Many are translated into Spanish. Gloucester........................... (856)307-4805 New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Hudson ................................ (201)223-1133 Office of Pollution Prevention and Right to Know Hunterdon ........................... (908)788-1110 PO Box 405 Mercer ................................. (609)278-7165 Trenton, NJ 08625-0405 Middlesex ............................ (732)745-8480 (609) 292-6714 Monmouth ........................... (732)431-7456 www.nj.gov/dep/opppc/crtk/ Morris .................................. (973)631-5485 Ocean .................................. (732)341-9700 Ext. 7477 Enforces the community provisions of the RTK Act in the private sector (except for labeling). -

Outline of Coverage Cherry Gulch Link HDHP $4200

Outline of Coverage Cherry Gulch Link HDHP $4200 Outline of Coverage | 2020 Benefit Plan Year December 1, 2020 – December 31, 2021 Benefit Accrual Period Calendar Year Deductible In-Network: Individual $4,200 Family $8,400 *Copayments and coinsurance do not accumulate to deductible. Out-of-Network: Individual $8,400 Family $16,800 In-Network: Individual $4,200 Family $8,400 Annual Out-of-Pocket Maximum Out-of-Network: Individual $8,400 Family $16,800 Coinsurance In-Network: 0% Out-of-Network: 0% Copayments are in addition to deductible and coinsurance. Once the Out-of-Pocket Copayment Maximum is satisfied; deductible, coinsurance and copayments do not apply. Deductible and coinsurance apply to all services as noted below. There is no lifetime maximum benefit limit for this plan. This is only a summary of benefits. Benefits and general provisions described herein are subject to the terms of the Member Guide and Group Contract. Prior Authorization is not a guarantee of payment but is recommended for some services, supplies, treatments, and prescription drugs to help the Member identify potential expenses, payment reductions, or claim denials that may occur if these proposed services are not Medically Necessary or not a Covered Medical Expense. Refer to your Member Guide. The member is responsible for the above deductible and the following copays and coinsurance: Services In-Network: Out-of-Network: Preventive Care Preventive Health Care Services for health care screenings or preventive purposes submitted with a routine diagnosis will be covered at 100% of the Allowable Fee. This 0% after Deductible means that these Benefits are not subject to the Deductible, Coinsurance, Copayments, or Annual Out-of- Pocket Maximum when services are provided by an In-Network (Out of network-Well Child Care visits provider. -

Unions' Right to Information About Occupational Health Hazards Under the National Labor Relations Act*

COMMENT Unions' Right to Information About Occupational Health Hazards Under the National Labor Relations Act* Michelle C. Mentzert Recent union efforts to gain disclosure of the identity of workplace chemicals under the NLRA section 8(a)(5) duty to supply information have been met with a number of employer defenses, including trade se- crecy. After a criticalanalysis of a trilogy of recent Boardopinions in this area, the authorproposes first, that health hazardinformation be consid- eredpresumptively relevant to unions' representationalfunctions,and sec- ond, that employers be requiredthoroughly to substantiateclaims of trade secrecy before unions are required to bargain over methods of disclosure to protect that secrecy. The identity of chemicals to which workers are exposed should always be obtainablein some manner or another. I INTRODUCTION A. The Importance of Being Informed The issue of workers' right to know about occupational health hazards has received much legislative' and administrative2 attention in * The author wishes to thank Professor Jan Vetter and Larry Drapkin for their advice and assistance in the preparation of this comment. t J.D., 1984, University of California (Berkeley), B.A., 1977, Wesleyan University. 1. At least seven state legislatures have passed some form of worker right-to-know law since 1980: California, CAL. LAB. CODE §§ 6360-6399.9 (West 1982); Connecticut, CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 31-40c (West 1972); Maine, ME. REV. STAT. ANN. tit. 26, § 1701-1707 (1974); Michi- gan, MICH. COMp. LAWS ANN. § 408.1011 (1967); New York, N.Y. LAB. LAW § 875-883 (McKin- ney 1977); West Virginia, W. VA. CODE § 21-3-18 (1982); Wisconsin, WIs. -

Family-Centered Care in the NICU

A Quality Improvement Tool Kit for the PAIRED Initiative Family-Centered Care in the NICU The Family-Centered Care PAIRED Initiative tool kit is intended to provide guidance to hospitals and neonatal providers in the development of individualized policies and protocols related to promoting family-centered care. It is not to be construed as a standard of care; rather it is a collection of resources that may be adapted by local institutions in order to develop standardized approaches to family-centered care. The tool kit will be updated as additional resources become available. Suggested Citation: Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative. (2021). Family-Centered Care in the NICU: A Quality Improvement Tool Kit for the PAIRED Initiative Acknowledgements: The FPQC gratefully acknowledges and thanks the Florida Department of Health for support of this initiative. The creation of this tool kit would not have been possible without the volunteer members of our Infant Health Subcommittee, including the members of the PAIRED Advisory Committee listed in this tool kit. Funding: This quality improvement (QI) initiative is funded in part by the Florida Department of Health with funds from the Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grant from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. Contact: Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative The Chiles Center Phone: (813) 974-5865 University of South Florida College of Public Fax: (813) 974-8889 Health E-mail: [email protected] 3111 East Fletcher Avenue Website: FPQC.org Tampa, FL 33613-4660 Copyright: © 2021 Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative. All Rights Reserved. The material in this tool kit may be reproduced and disseminated in any media in its original format, for informational, educational and non-commercial purposes only.