ARCHITECTURE and SCULPTURE from PHASE I 2.1 the Mauryan Period in Gandhara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

192. Great Stupa at Sanchi Madhya Pradesh, India. Buddhist, Maurya

192. Great Stupa at Sanchi Madhya Pradesh, India. Buddhist, Maurya, late Sunga Dynasty. c. 300 B.C.E. – 100 C.E. Stone masonry, sandstone on dome The Great Stupa at Sanchi is the oldest stone structure in India[1] and was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE built over the relics of the Buddha It was crowned by the chatra, a parasol-like structure symbolising high rank, which was intended to honour and shelter the relics 54 feet tall and 120 feet in diameter The construction work of this stupa was overseen by Ashoka's wife, Devi herself, who was the daughter of a merchant of Vidisha. Sanchi was also her birthplace as well as the venue of her and Ashoka's wedding. In the 1st century BCE, four elaborately carved toranas (ornamental gateways) and a balustrade encircling the entire structure were added With its many tiers it was a symbol of the dharma, the Wheel of the Law. The dome was set on a high circular drum meant for circumambulation, which could be accessed via a double staircase Built during many different dynasties . An inscription records the gift of one of the top architraves of the Southern Gateway by the artisans of the Satavahana king Satakarni: o "Gift of Ananda, the son of Vasithi, the foreman of the artisans of rajan Siri Satakarni".[ o Although made of stone, they were carved and constructed in the manner of wood and the gateways were covered with narrative sculptures. They showed scenes from the life of the Buddha integrated with everyday events that would be familiar to the onlookers and so make it easier for them to understand the Buddhist creed as relevant to their lives At Sanchi and most other stupas the local population donated money for the embellishment of the stupa to attain spiritual merit. -

Unit 26 Art and Architecture

UNIT 26 ART AND ARCHITECTURE Structure Objectives Introduction Background Architecnrre 26.3.1 Residential Architecture 26.3.2 Temples and Towers 26.3.3 Stupas 26.3.4 Rock-cut Architecture Sculptural Art 26.4.1 Gandhara School 26.4.2 Mathura Art 26.4.3 Amaravati Art Let Us Sum Up Key Words Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 26.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit you will be able to : familiarise yourself with important trends of art and architectural activities between 200 B.C. to 300 A.D. learn about the techniques and styles adopted in the fields of architecture and sculpture, distinguish between the major characteristics and forms of the Gandhara, Mathura and Amravati schools of art, and learn about the impact of religious and social conditions on art and architecture of the period. 26.1 INTRODUCTION In some of the earlier Units (Nos. 3, 10, 11) we have seen how artistic forms had started emerging and to what extent they reflected the culture of a period. Works of art which were related to work processes of daily life and were not exclusively produced for a previleged group of society were many. They are found in the forms of rock paintings, terracotta figurines, toys, etc. Gradually works of art, manufactured by specialist craftsmen, came to be produced for exclusive purposes. The Mauryan period witnessed production of splendid specimens of art by the state. With the emergence of social groups who could extend substal patronage for production of specimens of art, new trends in art activities came about. -

Lotus Bud Finial Asana Pose the Great Stupa at Sanchi Sakyamuni

Resources: https://www.britannica.com/techn ology/pagoda, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/arti TITLE: Pagoda (replica) cles/i/iconography-of-the- ARTIST: Unknown buddha/, DATE: Unknown http://fsu.kanopystreaming.com/vi SIZE: Height: 3 ¾; Width: 2 ¼; Depth: 1 7/8 inches deo/great-stupa-sanchi, MEDIUM: Wood https://prezi.com/nzoahwiq3owv/t AQUISTION #: 88.1.7 odaiji-the-great-eastern-temple/, http://thekyotoproject.org/english/ ADDITIONAL WORKS BY THE ARTIST IN COLLECTION? pagodas/ YES _ NO_ UNKNOWN X Context In the third century BCE, Emperor Ashoka commissioned the first “Great Stupa” in Sanchi, India. A stupa is a large dome tomb that was created to house relics of the Buddha. The “Great Stupa” held the Buddha’s ashes and was constructed in three parts: a base, body, and decorative finial. The decorative finial is the crowning element located at the highest point of the stupa. Throughout many centuries the design of the stupa structure evolved from the rounded monument to the multi-storied structure now known as the pagoda. Constructed and adapted throughout East Asia, the common building materials consist of brick, wood, or stone. Pagodas also range in a variety of sizes. Some are towers with high reaching crowning pieces and others are short. Today any Pagoda is a pilgrimage site. The Great Stupa at Sanchi Sakyamuni Pagoda of Fogong Temple The wooden pagoda in Yingxian, China is the oldest tiered structure in the world. Built in 1056, the nine-story building is 67.31 meters high. With multiple pagoda structures located throughout the world, this was the first wooden structure completed under the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing Dynasties (1644-1912). -

The Buddha Project Part 1

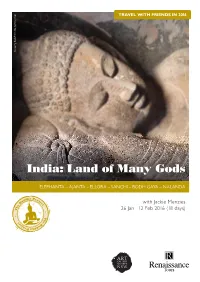

TRAVEL WITH FRIENDS IN 2016 Reclining Buddha in the Ajanta caves India: Land of Many Gods ELEPHANTA – AJANTA – ELLORA – SANCHI – BODH GAYA – NALANDA with Jackie Menzies 26 Jan– 12 Feb 2016 (18 days) India: Land of Many Gods The faith of over 300 million people, Buddhism encompasses the teachings of Siddhartha Guatama (the Buddha). Travelling through India, China, Korea and Japan immerse yourself in The Buddha Project as you follow the steps of this ancient religion. In this four part series of tours, visit heritage listed Buddhist caves, sacred temples and spiritually signifi cant sites that convey the complex heritage of this belief system. Begin the project with part one, India: Land of Many Gods, and see a nation that is home to the great religions of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. Visit Bodh Gaya, where TOUR LEADER the Buddha attained enlightenment; Ajanta, with its exquisite cave paintings; and idyllic Sanchi, fi lled with ancient monuments. This journey through India has been shaped by Jackie Menzies OAM is Emeritus Curator of Asian sites signifi cant to Buddhism, but major sites of other religions are also included. See Art at the Art Gallery of Elephanta with its superbly sculpted images; explore the vibrant sacred city of Varanasi; NSW, and has travelled widely tour the richly embellished Hindu temples of Khajuraho; and delve into the lives and through Asia. From 1979 to beliefs of India and her people. 2012 (as Head of Asian Art at AGNSW), she curated many exhibitions, and contributed At a glance… to scholarly catalogues on Asian -

Asoka's Dhamma

/ ASORA'S DIIAMMA - Ninnal C. Sinha A soka's place is second in the history of Dhamma, second only to ~he founder, Gautama Siddhartha the Buddha. Both Theravada (Southern Buddhist) and Mahayana (Northern Buddhist) traditions agree on this point that Asoka is second to Buddha. Nigrodha or Upagupta, Nagasena or Nagatjuna, both Theravada and Mahayana traditions agree, rank after Asoka. Brahmanical (Hindu) literary works extant bear testimony to Asoka being a great Buddhist. Kalhana in Rajatarangini (12th Cent. A.D.) records Asoka as having adopted the creed of Jina (= Buddha) and as the builder of numerous Stupas and Chaityas. Modem scholars, mostly European, however question the authenticity or purity of Asoka's Dhamma. Critics of Asoka notice the absence of Four Noble Truths, Eight Fold Path and Nirvana from Asoka's Edicts and point to Asoka's mention of Svaga (Svarga) or Heaven in the Edicts. Some scholars hint that Asoka's toleration policy was to accommodate Brahmanical faith while others label Asoka's Dhamma as his invention. In my submission Asoka was a Buddhist first and a Buddhist last. Asoka's own words, that is, Asoka's Edicts substantiate this finding. Inscriptions of Asoka were read and translated by pioneer scholars like Senart, Hultzsch, Bhandarkar, Barua and Woolner. I 5 cannot claim competence to improve on their work and extract mainly from the literal translation of Hultzsch (Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum: Volume I, London 1925). This ensures that I do not read my own meaning into any word of Asoka. For the same reason I use already done English translation ofPali/Sanskrit texts. -

Buddha in Art: from Symbol to Image

BUDDHA IN ART : FROM SYMBOL TO IMAGE Kalyankumar Ganguli There is a common impression about Buddhism that its impact was completely lost sight of in India long before the present age. Facts bearing to the contrary are, however, not quite rare to trace. One of the positive outcomes of the impact of Buddhism was probably the realisation of objects of veneration into techtonically formulated shapes held as images which have been used for the prupose of divination and worship. Realisation of divinities in visual form of idols and the worship of the same have been existing as a common phenQmenon among many ancient civilizations of the world. But in India there has been a marked difference in the phenomenon of image worship from the same as existing elsewhere. Here, the figure of the deity put into visual form is found to ha ve evolved as an aid in the endeavour on the part of the worshipper to attain concentration. It came to be tec\lJl.i<;;:ally known as a yantra or instrument which has been processed in order to help the worshipper to imbibe within his or her inner consciousness a complete identity with the object of veneration and full realisation of the essence of the same within one'llown inner self. In every possibility, as traditions may help in establishing, it had been through the endeavours of some thinkers owing allegiance to Buddhism that this aspect of image worship was evolved as a means of absorption and fulfilment. The realisation of this highly efficacious measure had not been accomplished all at once at a particular time. -

08-Luczanits-Engl:Layout Gandhara.Qxd 20.10.2008 17:29 Uhr Seite 72

08-Luczanits-engl:Layout Gandhara.qxd 20.10.2008 17:29 Uhr Seite 72 Christian Luczanits Early Buddhism and Gandhara Buddha Śākyamuni, who probably died, or entered parinirvāṇa, at around (cf. map 1, p. 31). These are all places in the central Ganges valley in 380 B.C.E., was born in the border region between India and Nepal where Northern India, a region that would play an important role in the history he also grew up. He lived and taught in a relatively small area in central of South Asia again and again. North India.1 This primary area of influence is defined by the main events Apparently, Buddhism had spread relatively far in a short amount of in his life: Lumbinī, the place of his birth, in the north, Bodhgāya, the time, and about 100 years after the Buddha’s death, the Maurya king place of his Awakening, in the south, Sārnāth, the place of his first ser- Aśoka was an especially effective catalyst for its propagation. In later Bud- mon, in the west, and Kuśinagara, the place of his death, in the east dhist legends, this is honoured and exalted accordingly. Thus, Aśoka had Fig. 1 Stupa 1 at Sanchi, whose core dates back to the time of Asoka 08-Luczanits-engl:Layout Gandhara.qxd 20.10.2008 17:29 Uhr Seite 73 been responsible for opening most of the nine stupas originally erected after the Buddha’s death in the core regions of Buddhism and spreading their relics even further (cf. Kuwayama, pp. 170ff.). Early Buddhism then originally manifests itself materially in the stupa, which first of all stands for a specific Buddha – or another Buddhist saint – whose relics were de- posited in its interior. -

The Locational Geography of Ashokan Inscriptions in the Indian Subcontinent

Antiquity http://journals.cambridge.org/AQY Additional services for Antiquity: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent Monica L. Smith, Thomas W. Gillespie, Scott Barron and Kanika Kalra Antiquity / Volume 90 / Issue 350 / April 2016, pp 376 - 392 DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2016.6, Published online: 06 April 2016 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0003598X16000065 How to cite this article: Monica L. Smith, Thomas W. Gillespie, Scott Barron and Kanika Kalra (2016). Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent. Antiquity, 90, pp 376-392 doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.6 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AQY, IP address: 128.97.195.154 on 07 Apr 2016 Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent Monica L. Smith1, Thomas W. Gillespie2, Scott Barron2 & Kanika Kalra3 The Mauryan dynasty of the third century BC was the first to unite the greater part of the Indian subcontinent under a single ruler, yet its demographic geography remains largely uncertain. Here, the HYDE 3.1 database of past population and land-use is used to offer insights into key aspects of Mauryan political geography through the locational analysis of the Ashokan edicts, which are the first stone inscriptions known from the subcontinent and which constitute the first durable statement of Buddhist-inspired beliefs. The known distribution of rock and pillar edicts across the subcontinent can be combined with HYDE 3.1 to generate predictive models for the location of undiscovered examples and to investigate the relationship between political economy and religious activities in an early state. -

Buddhist Heritage of the India..Pdf

Shrine, Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Buddhist sculpture and paintings are some of the gentlest and most sublime art of mankind. These are also the oldest surviving art of the historic period in the Indian subcontinent. Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl This photographic exhibition provides a comprehensive perspective of the monuments and art heritage of Buddhism, from the earliest times. It also takes us on a visual pilgrimage through the life of the Buddha: to the places of his birth, enlightenment, first sermon and final renunciation. Dhamek Stupa, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Chaitya-griha, Kushinagara, Uttar Pradesh, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Gilded statue of the Parinirvana, Kushinagara, Uttar Pradesh, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl The Buddha, 5th century AD, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Buddha in dharmachakrapravartana mudra, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, 5th century AD, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Kapilavastu, Piprawaha archaeological site, Uttar Pradesh, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Vaishali, Ananda stupa and Ashokan Pillar, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Stupa and Ashoka Pillar, Vaishali, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Angulimal Stupa, Sravasti, Uttar Pradesh, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Rajgir, Newly excavated stupa, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Stupa, Lauriya Nandangarh, Bihar, India. Photograph by Benoy K Behl Inscribed Column with Lion Capital, Lauriya Nandangarh, Bihar, India Photograph by Benoy K Behl Ashokan Edict carved on the shaft of the pillar, Lauriya Nandangarh, Bihar, India. -

South Kolkata Revised Syllabus History 2021 – 2022 Class

DELHI PUBLIC SCHOOL, (JOKA) SOUTH KOLKATA REVISED SYLLABUS HISTORY 2021 – 2022 CLASS XII FIRST PERIODIC ASSESSMENT Themes in Indian History Part-I (Units 1 – 3) • Unit 1: Bricks, Beads and Bones- The Story of the First Cities • Unit 2: Kings, Farmers and Towns- Political and Economic History • Unit 3: Kinship, Caste and Class -Social Histories SECOND PERIODIC ASSESSMENT Themes In Indian History Part I & Part-II (Units 3,4 And 6) • Unit 3: Kinship, Caste and Class -Social Histories • Unit 4: Thinkers, Beliefs and Buildings- A History of Buddhism • Unit 6: Religious Histories: The Bhakti-Sufi Tradition MIDTERM (THIRD PERIODIC ASSESSMENT) THEMES IN INDIAN HISTORY PART-II (UNITS 7, 9) • Unit7: New Architecture: Hampi • Unit 9: Kings and Chronicles -The Mughal Court • Unit 6: Religious Histories: The Bhakti-Sufi Tradition • ALONG WITH FULL Themes in Indian History Part-I (Units 1 – 4) MAP WORK: MAP 1- Mature Harappan sites • Harappa, Banawali, Kalibangan, Balakot, Rakhigarhi, Dholavira, Nageshwar, Lothal, Mohenjo-Daro, Chanhu-daro, Kot Diji. MAP 2- Mahajanapada and cities • Vajji, Magadha, Kosala, Kuru, Panchala, Gandhara, Avanti, Rajgir, Ujjain, Taxila, Varanasi. MAP 3 • Distribution of Ashokan inscriptions: Kushanas, Shakas, Satavahanas, Vakatakas, Guptas • Cities/towns: Mathura, Kanauj, Puhar, Braghukachchha, Shravasti, Rajgir, Vaishali, Varanasi, Vidisha • Pillar inscriptions- Sanchi, Topra, Meerut Pillar and Kaushambi. • Kingdom of Cholas , Cheras and Pandyas. MAP 4- Major Buddhist Sites: • Nagarjunakonda, Sanchi, Amaravati, Lumbini, -

Ashokan Inscriptions Occupy a Very Significant

04* 9? 86* rt T" •\ / Y. THEASHOKANli'" - ' -- Ss ■INSGRIBJIONS^ 1 * ■ »• • ■ I V* | * SHAHBA2GARHI IMANSEH J- - I KANDAHAR iC y KALSI 'TOPRA * ^ MEtRUi ■1NT- j •i. •: •. BAHAPUR '"^.iRAM PQR WA^'^'* rV" V/ •"•">' ALIS AR / < ,1. .. ' .*v- BAIRAT RU DEI LAURIY/^# . - ,«* J L. BHABRU NANDkrBA-NGARtH •LAURiYA ARAFWtr--r. ... .. / ; V UJ^RRA#-. • X rV"' * T' .« KAUSHAMpiA^A^ .r 9 * .yi.v' **'»' SAH/^RANl • , • ; AHRAURA#. .-4 .:KO •r »r* a rI OJJAYINI # SANCHI M I r Isr AGIRNAR (TV# : MYANMA SOPARA ARABIAN . •SHIStltlPALGARH ^ SEA '■ jaugadaV asannati *• KALI NG Ay BAY OF BENGAL . RAJULA : MANDAGIRI . : MASKI G AVI MATH UDEGOLAM PALK1GUNDU ■i NITTUR BRAHMAGIRI p™ UR JATINGA ? RAMESHWAR REFERENCES • « r ~ « £ % y. CHOLA A MAJOR ROCK EDICTS <A 8 V -J- . AN DAM A. ♦ _/{ SEA m. ■ MINOR ROCK EDICTS • PILLAR INSCRIPTIONS -u N D N O C E A -X- -l- Scanned with CamScanner .. ^ V V" /Vsliokau Inscriptions Ashokan inscriptions occupy a very significant place in the history of India. They ai;c very helpful in reconstructing the history of the Mauryan period. Undoubtedly, Ashoka was the first ruler in the history of India who spoke directly to his people through Scanned with CamScanner his inscriptions and got engraved his5 eddicts on stones. These inscriptions have been found on stones, polished stone pillars and the walls of the caves.. The inscriptions on rocks are called Rock Edicts and those, on pillars pillar Edicts. The inscriptions ■ of Ashoka have been found in India, Nepal, Pakistan ■ aiid Afghanistan. V T ■ v ; . The Ashokan inscriptions can be divided in the following categories; 1. The Rock Edicts Of Ashokan Rock Edicts the fourteen Rock Edicts are the most important.