THE CRAYON MISCELLANY, Part 1, Containing a Tour on the Prairies, by the Author of the Sketch Book, &C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dialects of Marinduque Tagalog

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS - Se�ie� B No. 69 THE DIALECTS OF MARINDUQUE TAGALOG by Rosa Soberano Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Soberano, R. The dialects of Marinduque Tagalog. B-69, xii + 244 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1980. DOI:10.15144/PL-B69.cover ©1980 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PAC IFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Ling ui6zic Ci�cle 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONA L PAPERS SER IES B - MONOGRAPHS SER IES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS EDITOR: S.A. Wurm. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. Bender, University of Hawaii J. Lynch, University of Papua New Guinea D. Bradley, University of Melbourne K.A. McElhanon, University of Texas A. Capell, University of Sydney H. McKaughan, University of Hawaii S. Elbert, University of Hawaii P. Muhlhausler, Linacre College, Oxfor d K. Franklin, Summer Institute of G.N. O'Grady, University of Victoria, B.C. Linguistics A.K. Pawley, University of Hawaii W.W. Glover, Summer Institute of K. Pike, University of Michigan; Summer Linguistics Institute of Linguistics E.C. Polom , University of Texas G. Grace, University of Hawaii e G. Sankoff, Universit de Montr al M.A.K. Halliday, University of e e Sydney W.A.L. Stokhof, National Centre for A. Healey, Summer Institute of Language Development, Jakarta; Linguistics University of Leiden L. -

Applications and Decisions

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WEST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 5446 PUBLICATION DATE: 15 March 2016 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 05 April 2016 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic -commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 29/03/2016 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e -mail. To use this service please send an e- mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS Important Information All post relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Jubilee House Croydon Street Bristol BS5 0DA The public counter in Bristol is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5 ) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. -

Geology and Mineral Resources of Douglas County

STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1069 State Office Building Portland, Oregon 97201 BU LLE TIN 75 GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES of DOUGLAS COUNTY, OREGON Le n Ra mp Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries The preparation of this report was financially aided by a grant from Doug I as County GOVERNING BOARD R. W. deWeese, Portland, Chairman William E. Miller, Bend Donald G. McGregor, Grants Pass STATE GEOLOGIST R. E. Corcoran FOREWORD Douglas County has a history of mining operations extending back for more than 100 years. During this long time interval there is recorded produc tion of gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, mercury, and nickel, plus lesser amounts of other metalliferous ores. The only nickel mine in the United States, owned by The Hanna Mining Co., is located on Nickel Mountain, approxi mately 20 miles south of Roseburg. The mine and smelter have operated con tinuously since 1954 and provide year-round employment for more than 500 people. Sand and gravel production keeps pace with the local construction needs. It is estimated that the total value of all raw minerals produced in Douglas County during 1972 will exceed $10, 000, 000 . This bulletin is the first in a series of reports to be published by the Department that will describe the general geology of each county in the State and provide basic information on mineral resources. It is particularly fitting that the first of the series should be Douglas County since it is one of the min eral leaders in the state and appears to have considerable potential for new discoveries during the coming years. -

Complex Price Dynamics in Vertically Linked Cobweb Markets in Less Developed Countries

Complex Price Dynamics in Vertically Linked Cobweb Markets in Less Developed Countries Muhammad Imran Chaudhry Karachi School for Business & Leadership Karachi, Pakistan imran.chaudhry@ksbl. edu.pk Mario J. Miranda Department of Agricultural, Environmental & Development Economics The Ohio State University Columbus, OH, USA [email protected] February 16, 2017 Abstract Advances in nonlinear dynamics have resuscitated interest in the theory of endogenous price fluctuations. In this paper, we enrich the traditional cobweb model by incorporating vertical linkages between agricultural markets, an important aspect of agricultural production in less developed countries that has been largely ignored by the existing literature on chaotic cobweb models. To this end, under sufficiently general cost and demand functions, we develop a parsimonious, dynamic model to capture mutual interdependencies between upstream and downstream markets arising from the vertically linked structure of agricultural values chains. The model is solved under the naïve expectations hypothesis to derive a system of coupled, time- delay difference equations characterizing price dynamics in vertically linked cobweb markets. Mathematical and numerical analyses reveal that vertical linkages between downstream and upstream cobweb markets have profound effects on local stability, global price dynamics and onset of chaos. We also add an empirical dimension to an otherwise theoretical literature by benchmarking moments of prices simulated by our model against actual poultry value chain price data from Pakistan. Simulated prices reproduce the stylized patterns observed in the actual price data, i.e., quasi-periodic behavior, positive first-order autocorrelation, relatively higher variation in upstream prices compared to downstream prices, low skewness and negative kurtosis. In doing so the paper addresses a major criticism of the theory of endogenous price fluctuations, most notably the failure of chaotic cobweb models to adequately replicate positively autocorrelated prices. -

Oneirohtane.Pdf

1 1 2 Πέρασαν µέρες χωρίς να στο πω το Σ’ αγαπώ, δυο µόνο λέξεις. Αγάπη µου πως θα µ΄ αντέξεις που είµαι παράξενο παιδί, σκοτεινό. Πέρασαν µέρες χωρίς να σε δω κι αν σε πεθύµησα δεν ξέρεις, κοντά µου πάντα θα υποφέρεις, σου το χα πει ένα πρωί βροχερό Θα σβήσω το φως κι όσα δεν σου χω χαρίσει σ’ ένα χάδι θα σου τα δώσω, κι ύστερα πάλι θα σε προδώσω µες του µυαλού µου το µαύρο Βυθό. Θα κλάψεις ξανά αφού µόνη θα µείνεις, κι εγώ ποιο µόνος κι από µένα, µες σε δωµάτια κλεισµένα το πρόσωπό σου θα ονειρευτώ, γιατί είµαι στ’ όνειρο µόνος µου. 2 3 Όνειρο Ήτανε ∆ηµήτρης 2001 3 4 Εισαγωγή Όλοι µας κάθε νύχτα βλέπουµε αµέτρητα όνειρα µε διάφορα περιεχόµενα. Άλλες φορές όµορφα, άλλες φορές άσχηµα, χαρούµενα, έντονα, θλιβερά, βαρετά, αγχωτικά. Έχει κανείς αναρωτηθεί τι είναι το όνειρο; Βιάστηκαν οι επιστήµονες να το εξηγήσουν. Υποθέτω θα το όριζαν σαν µια αναδροµή στο ασυνείδητο ή στο υποσυνείδητο. Να µε συγχωρέσουν αλλά έχω αντίθετη άποψη! Εγώ θα σας πω ότι το όνειρο ή µάλλον ο κόσµος των ονείρων, είναι κάτι το πραγµατικό. Ναι! Κάτι το πραγµατικό. Είναι ένας Κόσµος στον οποίον µεταφερόµαστε µε τον ύπνο... σαν να ταξιδεύει η ψυχή µας και να µπαίνει σε ένα άλλο υλικό σώµα, σε κάποια άλλη διάσταση. Ένας κόσµος στον οποίο δεν ισχύουν οι νόµοι, οι φυσικοί νόµοι που ισχύουν σε αυτόν που ζούµε όταν είµαστε ξύπνιοι! ∆εν χρειάζεται να έχεις φτερά για να πετάξεις, ούτε χρειάζεται να πονάς όταν χτυπάς. Έτσι λοιπόν η ψυχή ακούραστη πηγαίνει από το ένα σώµα στο άλλο, από την µία διάσταση στην άλλη, από κάποιους νόµους σε κάποιους άλλους. -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour -

These Eyes Before

collidethese eyes before Classic yet Modern... If you’re already familiar with Collide, you surely know that the duo’s brave, forward-looking electronic sound is deeply grounded in a fusion of diverse influences (hence the band’s chosen name). Over the years, singer kaRIN and pro- ducer Statik have proven themselves to be gifted interpreters as well as courageous innovators – consider their brooding take on the Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit”, a highlight of 2000’s landmark Chasing The Ghost, or their expansive take on Dusty Springfield’s “Son Of A Preacher Man”, from the remix set Distort, and the beloved anthem “The Lunatics are Taking Over the Asylum”, from their Vortex album. But nothing in the group’s history will sufficiently prepare you for These Eyes Before: a set of ten mainstream classics, each one completely reimagined by the imaginative pair. We don’t want to ruin all of Collide’s surprises, since part of the joy of listening to These Eyes Before is encountering familiar material with utterly refreshing arrangements. And you will be familiar with the playlist – any real music fan will be able to sing along to the tunes kaRIN and Statik have selected. Also, we don’t want to single out any highlights, because a project like this one is nothing but highlights. But we’d be remiss if we didn’t crow about the group’s flexibility, and their unerring ability to make songs of all kinds seem utterly consistent with the sound they’ve been developing for the past fifteen years. In their hands, “Space Oddity” becomes a gorgeous, jazzy, ethereal techno-rock stroll, and David Essex’s swaggering “Rock On” turns into a deliciously distorted slice of trip-hop. -

Foreign Seeds and Plants

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. DIVISION OF BOTANY. IXVENTOJIY NO. 7. FOREIGN SEEDS AND PLANTS IMPORTED JiY THE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THROUGH THE SECTION OF SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION, FOR DISTRIBUTION IN COOPERA- TION WITH THE STATE AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATIONS. NUMBERS 2701-3400. INVENTORY OF FOREIGN SEEDS AND PLANTS. INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT. The present inventoiy or catalogue of seeds and plants includes the collections of the agricultural explorers of the Section of Seed and Plant Introduction, as well as a large number of donations from mis- cellaneous sources. There are a series of new and interesting vege- tables, field crops, ornamentals, and forage plants secured by Mr. Walter T. Swingle in France, Algeria, and Asia Minor. Another important exploration was that conducted by Mr. Mark A. Carleton, an assistant in the Division of Vegetable Physiology and Pathology. The wheats and other cereals were published in Inventoiy No. 4, but notices of many of Mr. Carleton\s miscellaneous importations are printed here for the first time. The fruits and ornamentals collected by Dr. Seaton A. Knapp in Japan are here listed, together with a number of Chinese seeds from the Yangtze Valley, presented by Mr. G. D. Brill, of Wuchang. Perhaps the most important items are the series of tropical and subtropical seeds and plants secured through the indefatigable efforts of Hon. Barbour Lathrop, of Chicago. Mr. Lathrop, accompanied by Mr. David G. Fairchild, formerly in charge of the Section of Seed and Plant Introduction, conducted at his own expense an extended exploration through the West Indies, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Brazil, and Argentina, and procured many extremely valuable seeds and plants, some of which had never been previously introduced into this country. -

Stories of Classic Myths Historical Stories of the Ancient World and the Middle Ages Retold from St

Class Rnnk > 5 Copyright N? V — COPYRIGHT DEPOSITS . “,vV* ’A’ • *> / ; V \ ( \ V •;'S' ' » t >-i { ^V, •; -iJ STORIES OF CLASSIC MYTHS HISTORICAL STORIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD AND THE MIDDLE AGES RETOLD FROM ST. NICHOLAS MAGAZINE IN SIX VOLUMES STORIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD The beginnings of history: Egypt, Assyria, and the Holy Land. STORIES OF CLASSIC MYTHS Tales of the old gods, goddesses, and heroes. STORIES OF GREECE AND ROME Life in the times of Diogenes and of the Caesars. STORIES OF THE MIDDLE AGES History and biography, showing the manners and customs of medieval times. STORIES OF CHIVALRY Stirring tales of ‘‘the days when knights were bold and ladies fair.” STORIES OF ROYAL CHILDREN Intimate sketches of the boyhood and girl- hood of many famous rulers. Each about 200 pages. 50 illustrations. Full cloth, 12mo. THE CENTURY CO. STORIES OF CLASSIC MYTHS RETOLD FROM ST. NICHOLAS NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1909 Copyright, 1882, 1884, 1890, 1895, 1896, 1904, 1906, 1909, by The Century Co. < ( < i c the devinne press 93 CONTENTS Jason and Medea Frontispiece PAGE The Story of the Golden Fleece Andrew Lang 3 The . Labors of Hercules C. L B I ... ^ The Boys at Chiron’s School . Evelyn Muller 69 The Daughters of Zeus .... D . 0 . S. Lowell 75 The Story of Narcissus .... Anna M. Pratt 91 The Story of Perseus Mary A . Robinson 96 King Midas Celia Thaxter \ 04 The Story of Pegasus .... M. C. 1 1 . James Baldwin 1 Some Mythological Horses 1 Phaeton The Crane’s Gratitude .... Mary E . Mitchell 140 D^dalus and Icarus Classic Myths C. -

Elisabeth Haich

Elisabeth Haich INITIATION AUTHOR'S NOTE It is far from my intentions to want to provide a historical picture of Egypt. A person who is living in any given place has not the faintest idea of the peculiarities of his country, and he does not consider customs, language and religion from an ethnographic point of view. He takes everything as a matter of course. He is a human being and has his joys and sorrows, just like every other human being, anywhere, any place, any time; for that which is truly human is timeless and changeless. My concern here is only with the human, not with ethnography and history. That is why I have, in relating the story which follows here, intentionally used modern terms. I have avoided using Egyptian sounding words to create the illusion of an Egyptian atmosphere. The teachings of the High Priest Ptahhotep are given in modern language so that modern people may understand them. For religious symbols also, I have chosen to use modern terms so that all may understand what these symbols mean. People of today understand us better if we say 'God' than if we were to use the Egyptian term 'Ptah' for the same concept. If we say 'Ptah' everyone immediately thinks, 'Oh yes, Ptah, the Egyptian God'. No! Ptah was not an Egyptian God. On the contrary, the Egyptians called the same God whom we call God, by the name of Ptah. And to take another example, their term for Satan was Seth. The words God and Satan carry meanings for us today which we would not get from the words Ptah or Seth. -

Mascware Songbook

mascware Songbook mascware Songbook Version 1.10 20.11.2009 Dieses Songbook ist lediglich eine Ansammlung von Songs von den verschiedensten öffentlich zugänglichen Quellen des Internets zusammengetragen. Die Urheberrechte an den einzelnen Songtexten liegen bei den jeweiligen Interpreten, deren Erben, einer Plattenfirma oder wem auch immer. Meine Leistung bestand nur darin, vermeintliche Fehler zu korrigieren, die Texte zur besseren Lesbarkeit zu formatieren und um entsprechende Strumming- und Picking-Vorschläge zu ergänzen. Die Songtexte sind nur für den privaten Gebrauch oder Studium bestimmt. Die Verbreitung und kommerzielle Nutzung ist untersagt. Anregungen sind jederzeit willkommen: [email protected] ☺ © 2009 by Martin Schüle Version 1.10 1 mascware Songbook 3 Doors Down - Here Without You ............................................. 6 4 Non Blondes - What's Up ................................................... 8 Adriano Celentano - Una Festa Sui Prati ..................................... 9 America - A Horse With No Name ............................................. 10 Animals - House Of The Rising Sun .......................................... 11 Art Garfunkel - Bright eyes ................................................ 12 BAP - Verdamp lang her ..................................................... 13 Barclay James Harvest - Hymn ............................................... 14 Barry McGuire - Eve Of Destruction ......................................... 16 Beach Boys – Sloop John B ................................................. -

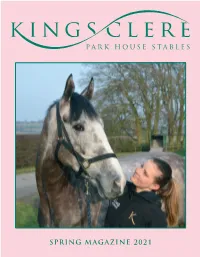

Spring Magazine 2021 Introduction P Ark House Stables Amb

P ARK HOUSE STABLES SPRING MAGAZINE 2021 INTRODUCTION P ARK HOUSE STABLES AMB t is hard to believe that twelve months have passed since we first entered a COVID-19 lockdown. 2020 is a year that few people will want to Iremember, with hardships for so many. There is, however, light at the end of the tunnel, and as spring approaches and more people are vaccinated perhaps it is time to start believing that this summer might resemble something we probably all took for granted in pre-COVID years. Never again will I complain about not finding a parking space at the racecourse or having to queue for a coffee in the Owners & Trainers bar! With the prospect of normality approaching we have embarked upon some exciting new projects for the coming season. With our absolute priority remaining to achieve the best and safest working surfaces for the horses we have replaced the Side Glance gallop with an Activetrack surface from Martin Collins. This has already proved to be a huge success, as has the building of an arena to help with the re-training of a small selection of retired racehorses at Kingsclere and to give a further training option for BOUNCE THE BLUES gleaming in the winter sun as she heads out to exercise horses who need a change from the gallops. I am delighted to report the renewal of the King Power sponsorship of Front cover: Reunited – ARCTIC VEGA and devoted groom the yard for 2021, and with this support we have been anxious to improve Shelby Joubert the facilities for our human residents as well as the equine ones.