Levis Et Al EJN 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smoking Cessation Treatment at Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Programs

SMOKING CEssATION TREATMENT AT SUBSTANCE ABUSE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS Malcolm S. Reid, PhD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; Jeff Sel- zer, MD, North Shore Long Island Jewish Healthcare System; John Rotrosen, MD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry Cigarette smoking is common among persons with drug and alcohol n Nicotine is a highly use disorders, with prevalence rates of 80-90% among patients in sub- addictive substance stance use disorder treatment programs. Such concurrent smoking may that meets all of produce adverse behavioral and medical problems, and is associated the criteria for drug with greater levels of substance use disorder. dependence. CBehavioral studies indicate that the act of cigarette smoking serves as a cue for drug and alcohol craving, and the active ingredient of cigarettes, nicotine, serves as a primer for drug and alcohol abuse (Sees and Clarke, 1993; Reid et al., 1998). More critically, longitudinal studies have found tobacco use to be the number one cause of preventable death in the United States, and also the single highest contributor to mortality in patients treated for alcoholism (Hurt et al., 1996). Nicotine is a highly addictive substance that meets all of the criteria for drug dependence, and cigarette smoking is an especially effective method for the delivery of nicotine, producing peak brain levels within 15-20 seconds. This rapid drug delivery is one of a number of common properties that cigarette smok- ing shares with hazardous drug and alcohol use, such as the ability to activate the dopamine system in the reward circuitry of the brain. -

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D., M.P.H.; Joseph Guydish, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Jill Williams, M.D.; Marc Steinberg, Ph.D.; and Jonathan Foulds, Ph.D. Despite the high prevalence of tobacco use among people with substance use disorders, tobacco dependence is often overlooked in addiction treatment programs. Several studies and a meta-analytic review have concluded that patients who receive tobacco dependence treatment during addiction treatment have better overall substance abuse treatment outcomes compared with those who do not. Barriers that contribute to the lack of attention given to this important problem include staff attitudes about and use of tobacco, lack of adequate staff training to address tobacco use, unfounded fears among treatment staff and administration regarding tobacco policies, and limited tobacco dependence treatment resources. Specific clinical-, program-, and system-level changes are recommended to fully address the problem of tobacco use among alcohol and other drug abuse patients. KEY WORDS: Alcohol and tobacco; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use, abuse, dependence; addiction care; tobacco dependence; smoking; secondhand smoke; nicotine; nicotine replacement; tobacco dependence screening; tobacco dependence treatment; treatment facility-based prevention; co-treatment; treatment issues; treatment barriers; treatment provider characteristics; treatment staff; staff training; AODD counselor; client counselor interaction; smoking cessation; Tobacco Dependence Program at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey obacco dependence is one of to the other. The common genetic vul stance use was considered a potential the most common substance use nerability may be located on chromo trigger for the primary addiction. -

Cocaine Use Disorder

COCAINE USE DISORDER ABSTRACT Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem. Millions of Americans regularly use cocaine, and some develop a substance use disorder. Cocaine is generally not ingested, but toxicity and death from gastrointestinal absorption has been known to occur. Medications that have been used as substitution therapy for the treatment of a cocaine use disorder include amphetamine, bupropion, methylphenidate, and modafinil. While pharmacological interventions can be effective, a recent review of pharmacological therapy for cocaine use indicates that psycho-social efforts are more consistent over medication as a treatment option. Introduction Cocaine is an illicit, addictive drug that is widely used. Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem that burdens the healthcare system and that can be destructive to individual lives. It is impossible to know with certainty the extent of use but data from public health surveys, morbidity and mortality reports, and healthcare facilities show that there are millions of Americans who regularly take cocaine. Cocaine intoxication is a common cause for emergency room visits, and it is one drug that is most often involved in fatal overdoses. Some cocaine users take the drug occasionally and sporadically but as with every illicit drug there is a percentage of people who develop a substance use disorder. Treatment of a cocaine use disorder involves psycho-social interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com Pharmacology of Cocaine Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the Erthroxylum coca plant, a plant that is indigenous to South America and several other parts of the world, and is cultivated elsewhere. -

Alcohol Use Disorder

Section: A B C D E Resources References Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) Tool This tool is designed to support primary care providers (family physicians and primary care nurse practitioners) in screening, diagnosing and implementing pharmacotherapy treatments for adult patients (>18 years) with Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). Primary care providers should routinely offer medication for moderate and severe AUD. Pharmacotherapy alone to treat AUD is better than no therapy at all.1 Pharmacotherapy is most effective when combined with non-pharmacotherapy, including behavioural therapy, community reinforcement, motivational enhancement, counselling and/or support groups. 2,3 TABLE OF CONTENTS pg. 1 Section A: Screening for AUD pg. 7 Section D: Non-Pharmacotherapy Options pg. 4 Section B: Diagnosing AUD pg. 8 Section E: Alcohol Withdrawal pg. 5 Section C: Pharmacotherapy Options pg. 9 Resources SECTION A: Screening for AUD All patients should be screened routinely (e.g. annually or when indicators are observed) with a recommended tool like the AUDIT. 2,3 It is important to screen all patients and not just patients eliciting an index of suspicion for AUD, since most persons with AUD are not recognized. 4 Consider screening for AUD when any of the following indicators are observed: • After a recent motor vehicle accident • High blood pressure • Liver disease • Frequent work avoidance (off work slips) • Cardiac arrhythmia • Chronic pain • Rosacea • Insomnia • Social problems • Rhinophyma • Exacerbation of sleep apnea • Legal problems Special Patient Populations A few studies have reviewed AUD in specific patient populations, including youth, older adults and pregnant or breastfeeding patients. The AUDIT screening tool considered these populations in determining the sensitivity of the tool. -

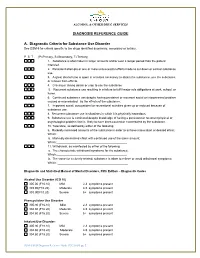

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders Second Edition WORK GROUP ON SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Herbert D. Kleber, M.D., Chair Roger D. Weiss, M.D., Vice-Chair Raymond F. Anton Jr., M.D. To n y P. G e o r ge , M .D . Shelly F. Greenfield, M.D., M.P.H. Thomas R. Kosten, M.D. Charles P. O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D. Bruce J. Rounsaville, M.D. Eric C. Strain, M.D. Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D. Grace Hennessy, M.D. (Consultant) Hilary Smith Connery, M.D., Ph.D. (Consultant) This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in August 2006. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available in the Psychiatric Practice section of the APA web site at www.psych.org. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. -

Substance Use Disorder Defined by NIDA and SAMHSA

Substance Use Disorder defined by NIDA and SAMHSA: NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) defines SUD/Addiction as: What is drug addiction? Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain. It is considered both a complex brain disorder and a mental illness. Addiction is the most severe form of a full spectrum of substance use disorders, and is a medical illness caused by repeated misuse of a substance or substances. Why study drug use and addiction? Use of and addiction to alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs cost the Nation more than $740 billion a year related to healthcare, crime, and lost productivity.1,2 In 2016, drug overdoses killed over 63,000 people in America, while 88,000 died from excessive alcohol use.3,4 Tobacco is linked to an estimated 480,000 deaths per year.5 (Hereafter, unless otherwise specified, drugs refers to all of these substances.) How are substance use disorders categorized? NIDA uses the term addiction to describe compulsive drug seeking despite negative consequences. However, addiction is not a specific diagnosis in the fifth edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)—a diagnostic manual for clinicians that contains descriptions and symptoms of all mental disorders classified by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). In 2013, APA updated the DSM, replacing the categories of substance abuse and substance dependence with a single category: substance use disorder, with three subclassifications—mild, moderate, and severe. The symptoms associated with a substance use disorder fall into four major groupings: impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and pharmacological criteria (i.e., tolerance and withdrawal). -

DSM-5 Diagnoses and New ICD-10-CM Codes

DSM-5 DiAgnoses And New ICD-10-CM Codes As Ordered in the DSM-5 Classification DSM-5 Recommended DSM-5 Recommended Disorder ICD-10-CM Code for use ICD-10-CM Code for use through September 30, 2017 beginning October 1, 2017 Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder F50.89 F50.82 Alcohol Use Disorder, Mild F10.10 F10.10 Alcohol Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained remission F10.10 F10.11 Alcohol Use Disorder, Moderate F10.20 F10.20 Alcohol Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or sustained F10.20 F10.21 remission Alcohol Use Disorder, Severe F10.20 F10.20 Alcohol Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F10.20 F10.21 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Mild F12.10 F12.10 Cannabis Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained F12.10 F12.11 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Moderate F12.20 F12.20 Cannabis Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or sustained F12.20 F12.21 remission Cannabis Use Disorder, Severe F12.20 F12.20 Cannabis Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F12.20 F12.21 remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Mild F16.10 F16.10 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Mild, In early or sustained F16.10 F16.11 remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Moderate F16.20 F16.20 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Moderate, In early or F16.20 F16.21 sustained remission Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Severe F16.20 F16.20 Phencyclidine Use Disorder, Severe, In early or sustained F16.20 F16.21 remission Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, Mild F16.10 F16.10 Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, Mild, In early or F16.10 F16.11 sustained remission Other Hallucinogen Use Disorder, -

A Review of the Use of Positive Reinforcement in Drug Courts Katherine Bascom Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine DigitalCommons@PCOM PCOM Psychology Dissertations Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers 2019 A Review of the Use of Positive Reinforcement in Drug Courts Katherine Bascom Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/psychology_dissertations Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bascom, Katherine, "A Review of the Use of Positive Reinforcement in Drug Courts" (2019). PCOM Psychology Dissertations. 509. https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/psychology_dissertations/509 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers at DigitalCommons@PCOM. It has been accepted for inclusion in PCOM Psychology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@PCOM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: POSITVE REINFORCEMENT IN DRUG COURTS Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine School of Professional and Applied Psychology A REVIEW OF THE USE OF POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT IN DRUG COURTS By Katherine Bascom © 2019 Katherine Bascom Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Psychology June 2019 DISSERTATION APPROVAL Th is is to certify th at the thesis presented to us by -----"/'-v-'-/k'-=l'--'1f1"'b"'-__..&"'-"'St;=6'-M____,___ _ ' on the ___,_9_fli ___ day of_----"-l't_._u,,_7_,__ _____, 2o_jj__, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology, has been examined and is acceptable in both scholarship and literary quality. COMMITTEE MEMBERS' SIGNATURES Chairperson Chair, Department of Clinical Psychology Dean, School of Professional & Applied Psycholog POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT IN DRUG COURTS iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee members, Dr. -

Substance Use Disorder Brochure

Substance Use Disorder & Addictioniction What is substance use disorder and addiction? Substance use disorder is using drugs or alcohol even though doing so causes problems in your life. Addiction is a physical or mental dependence on drugs or alcohol. This means when you stop using drugs or alcohol you could get sick. Addiction can also mean that you cannot stop thinking about substances. It’s bad for your health Substance use disorder affects you and those around you. Substance use disorder problems can lead to poor health, violence and arrest. It can also lead to you injuring others or even suicide. Studies show people with a substance addiction may also suffer from other mental health problems like depression. A person with a substance use disorder problem is not a bad person. They may need help from an expert. Without help, problems can get worse. Signs of a possible problem • Drinking in risky situations (while driving, swimming, etc.) • Continued use of alcohol or drugs despite personal or social problems • Obligations at work, home or school are neglected due to drinking or drug use • Legal problems related to drinking or drug use (domestic violence, assault or DUI) This page is intentionally left blank. Who offers substance use disorder services? Your Doctor: They can treat you or refer you to a specialist. Nurse Practitioner: They can be experts in substance use disorder and addiction, and can give medicine in most states. Therapist: Can provide psychotherapy, but cannot prescribe medicine. Some types of therapists are Licensed Mental Health Counselors (LMCH), and Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists (LMFT). -

Best Practices Across the Continuum of Care for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder

www.ccsa.ca • www.ccdus.ca Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder August 2018 Sheena Taha, PhD Knowledge Broker Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder This document was published by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA). Suggested citation: Taha, S. (2018). Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. © Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2018. CCSA, 500–75 Albert Street Ottawa, ON K1P 5E7 Tel.: 613-235-4048 Email: [email protected] Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada. This document can be downloaded as a PDF at www.ccsa.ca. Ce document est également disponible en français sous le titre : Pratiques exemplaires dans le continuum des soins pour le traitement du trouble lié à l’usage d’opioïdes ISBN 978-1-77178-507-5 Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 2 Method...................................................................................................................