Fifth Phase of an Architectural Survey In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRINGS of ARLINGTON Celebrating the Restoration of the Historical Donaldson Spring at Potomac Overlook Regional Park, May 1, 1988

SPRINGS OF ARLINGTON Celebrating the restoration of the historical Donaldson Spring at Potomac Overlook Regional Park, May 1, 1988. By Eleanor Lee Templeman What a lovely word, not only to name the most beautiful season, but to indicate water rising, or springing, from the earth! There is a certain magic in water flowing from the depths of dry soil. The surrounding dampness encourages the growth of ferns and wild flowers. Water is essential for the life of man, flora and fauna. The world's great deserts would have remained uninhabited without the oasis. From prehistoric times, springs have played an important role in the lives of humans. The Donaldson Spring in Potomac Overlook Regional Park was the site of an Indian hunting and fishing camp. There is evidence that it was also their burial ground. Pioneer families chose their home sites adjacent to springs, and many constructed stone springhouses over them. Here in the cool water were stored milk, butter and other perishables. Each spring has its individual tradition. The one which we honor today symbolizes the linking of two of the earliest local families, the Donaldsons and the Marceys, who intermarried as was the custom in rural communities. Throughout Virginia, all the most important plantation homes were estab lished adjacent to this important water supply. The abundance of springs on the hillside above the Potomac at Mount Vernon decided the house location and supplied water to the estate from the settlement of the first of the Washington family in the 1700s until a very recent date. Mount Vernon's former Director, Cecil Wall, since his retirement a few years ago, comes weekly to a flowing spring in the woods to fill his jug with the pure sweet water, refusing to drink from the municipal supply. -

Foundation Document Overview, Lyndon

Description NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RIVERBEND 189 PARK Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial R Great ive 495 r Falls Ro ad d R B Grove on the Potomac was established r s ic ll k a ya F r d Ro 190 ad Great Falls Park C&O CANAL by Congress on December 28, NATIONAL American Legion MARYLAND HISTORICAL Memorial Bridge PARK Exit 40 1973, through Public Law 93-211. C a Naval Surface Warfare Center b in Foundation Document Overview 495 (Carderock Division) Jo Washington, D.C. h Maryland n The memorial is intended to honor 738 P C M k a a thur B w O r cAr oule Clara Barton National Historic Site l d Exit 41 vard y d er o D ck President Lyndon B. Johnson and o G Clar m a Bar e ton Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove on the Potomac i o Parkw n rg a io e y ROCK n to Glen Echo Park w D n Exit 43 recognize his achievements in r i Pik CREEK v e n e u R 193 Turkey Run Park PARK District of Columbia y Parkway e preserving the nation’s environment, k Headquarters r u Exit 44 T l d a i R n 193 M.D. n o as well as his love of the land. It was l m VA. u 738 r o R a C F d a e D 495 privately funded and planned, but 123 Claude Moore Colonial Farm 123 267 was dedicated to the public as a unit Exit 45 t mi Run Little Pim G Falls Fort Marcy e Chain Bridge o of the National Park Service, serving rg WASHINGTON, e W anc 123 Exit 46 Br h a as a place where people can enjoy the 267 lf s u h D.C. -

Corridor Analysis for the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia

Corridor Analysis For The Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail In Northern Virginia June 2011 Acknowledgements The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this report: Don Briggs, Superintendent of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail for the National Park Service; Liz Cronauer, Fairfax County Park Authority; Mike DePue, Prince William Park Authority; Bill Ference, City of Leesburg Park Director; Yon Lambert, City of Alexandria Department of Transportation; Ursula Lemanski, Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program for the National Park Service; Mark Novak, Loudoun County Park Authority; Patti Pakkala, Prince William County Park Authority; Kate Rudacille, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; Jennifer Wampler, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation; and Greg Weiler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The report is an NVRC staff product, supported with funds provided through a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Region National Park Service. Any assessments, conclusions, or recommendations contained in this report represent the results of the NVRC staff’s technical investigation and do not represent policy positions of the Northern Virginia Regional Commission unless so stated in an adopted resolution of said Commission. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the jurisdictions, the National Park Service, or any of its sub agencies. Funding for this report was through a cooperative agreement with The National Park Service Report prepared by: Debbie Spiliotopoulos, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission with assistance from Samantha Kinzer, Environmental Planner The Northern Virginia Regional Commission 3060 Williams Drive, Suite 510 Fairfax, VA 22031 703.642.0700 www.novaregion.org Page 2 Northern Virginia Regional Commission As of May 2011 Chairman Hon. -

Arlington County, Virginia (All Jurisdictions)

VOLUME 1 OF 1 ARLINGTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ARLINGTON COUNTY, 515520 UNINCORPORATED AREAS PRELIMINARY 9/18/2020 REVISED: TBD FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 51013CV000B Version Number 2.6.4.6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Page SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The National Flood Insurance Program 1 1.2 Purpose of this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 1.3 Jurisdictions Included in the Flood Insurance Study Project 2 1.4 Considerations for using this Flood Insurance Study Report 2 SECTION 2.0 – FLOODPLAIN MANAGEMENT APPLICATIONS 13 2.1 Floodplain Boundaries 13 2.2 Floodways 17 2.3 Base Flood Elevations 18 2.4 Non-Encroachment Zones 19 2.5 Coastal Flood Hazard Areas 19 2.5.1 Water Elevations and the Effects of Waves 19 2.5.2 Floodplain Boundaries and BFEs for Coastal Areas 21 2.5.3 Coastal High Hazard Areas 21 2.5.4 Limit of Moderate Wave Action 22 SECTION 3.0 – INSURANCE APPLICATIONS 22 3.1 National Flood Insurance Program Insurance Zones 22 SECTION 4.0 – AREA STUDIED 22 4.1 Basin Description 22 4.2 Principal Flood Problems 23 4.3 Non-Levee Flood Protection Measures 24 4.4 Levees 24 SECTION 5.0 – ENGINEERING METHODS 27 5.1 Hydrologic Analyses 27 5.2 Hydraulic Analyses 32 5.3 Coastal Analyses 37 5.3.1 Total Stillwater Elevations 38 5.3.2 Waves 38 5.3.3 Coastal Erosion 38 5.3.4 Wave Hazard Analyses 38 5.4 Alluvial Fan Analyses 39 SECTION 6.0 – MAPPING METHODS 39 6.1 Vertical and Horizontal Control 39 6.2 Base Map 40 6.3 Floodplain and Floodway Delineation 41 6.4 Coastal Flood Hazard Mapping 51 6.5 FIRM -

Discover the Potomac Gorge

Discover the Potomac Gorge: A National Treasure n the outskirts of Washington, D.C., O the Potomac River passes through a landscape of surprising beauty and ecological significance. Here, over many millennia, an unusual combination of natural forces has produced a unique corridor known as the Potomac Gorge. This 15-mile river stretch is one of the country’s most biologically diverse areas, home to more than 1,400 plant species. Scientists have identified at least 30 distinct natural vegetation communities, several of which are globally rare and imperiled. The Gorge also supports a rich array of animal life, from rare invertebrates to the bald eagle and fish like the American shad. g g n n In total, the Potomac Gorge provides habitat to i i m m e e l l F F more than 200 rare plant species and natural . P P y y r r communities, making it one of the most important a a G G © © natural areas in the eastern United States. The heart of the Potomac Gorge is also known as Mather Gorge, named This riverside prairie at Great Falls, Virginia, results from periodic river flooding, after Stephen T. Mather, first director of the National Park Service. a natural disturbance that creates and sustains rare habitats. g g g n n n i i i e n m m m e r y e e e l l l a e l F F F P C . y e P P P e L y y y v f r r r r f a a a a e G G H G J © © © © © Flowering dogwood, a native forest understory species in our Specially adapted to withstand river The Potomac Gorge is home to Clinging precariously to the cliff’s edge, Brightly colored in its immature form, a reptile known as the region, is being decimated by an introduced fungal disease. -

46 Pola Negri in 1927

Courtesy LofC, Prints & Photo Div, LC-DIG-ggbain-37938 Pola Negri in 1927 46 ARLINGTON HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Pola Negri Slept Here? Unraveling the Mystery of a Screen Siren's Stay in Arlington BY JENNIFER SALE CRANE With Arlington having few Hollywood connections to boast of, save For rest Tucker, Warren Beatty, Shirley MacLaine, and Sandra Bullock, the story about a modest stone bungalow nestled in the Gulf Branch stream valley off of Military Road is curious indeed. According to a long-held local legend, silent film star Pola Negri once stayed there. Local accounts have varied- some say the house was rented by Negri as her "Virginia hideaway," others think it was built as Negri and Rudolph Valen tino's love nest, and played host to Hollywood-style pool parties. The cozy bungalow at 3608 N. Military Road, 1 with quite a few additions and alterations, is now home to the Gulf Branch Nature Center, established in 1966 and operated by Arlington County Department of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources. The swimming pool, filled in and planted with a garden, can still be identified by the exposed segments of its curved concrete walls. The Nature Center's connection to the early Hollywood star was investi gated in the 1970s by ComeliaB. Rose, Jr., a founding member of the Arlington Historical Society. Rose's documentation leaves a few questions unanswered. But despite the lack of unequivocal primary source evidence, the story of Pola egri and the Gulf Branch Nature Center has become an important part of the oral tradition of Arlington County. -

Natural Resources Management Plan Background…

ARLINGTON COUNTY NATURAL HERITAGE RESOURCE INVENTORY AND NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN BACKGROUND… PUBLIC SPACES MASTER PLAN (2005) “CREATE A NATURAL RESOURCE INVENTORY AND TO DEVELOP A MANAGEMENT STRATEGY FOR NATURAL RESOURCE PROTECTION” • Bring together various plans & practices to protect the County’s natural resources. • Develop a classification system of the various types of natural resources. • Define lines of authority & responsibilities among various agencies. • Create an additional GIS Layer to identify significant natural resources. NATURAL HERITAGE RESOURCE INVENTORY: LAYING THE GROUNDWORK…2005-2008 ARLINGTON’S FIRST COMPREHENSIVE NATURAL RESOURCE INVENTORY…. Partnership development… PROJECT ELEMENTS: WATER RESOURCES GEOLOGY NATIVE FLORA TREE RESOURCES INVASIVE PLANTS URBAN WILDLIFE GIS WATER RESOURCES… SPRINGS AND SEEPS STREAM MAPPING WETLANDS CONSTRUCTED WETLANDS GEOLOGICAL FEATURES… SCENIC WATERFALLS OUTCROPS HIGH VALUE EXPOSURES HISTORIC QUARRIES NATIVE FLORA… LOCALLY-RARE PLANTS NATIVE FLORA STATE-RARE PLANTS SPECIMEN PREPARATION NATIVE PLANT COMMUNITIES & TREE RESOURCES… CHAMPION TREES SIGNIFICANT TREES FOREST TYPES PLANT COMMUNITIES INVASIVE PLANTS… 500 acres of parkland mapped… GOOSEBERRY FIVE-LEAVED AKEBIA ENGLISH IVY “Invasive plants represent the greatest current threat to the natural succession of local native forests in Arlington County” URBAN WILDLIFE: LEPIDOPTERA AVIFAUNA AMPHIBIANS ODONATA REPTILES MAMMALS GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM (GIS) … Mapping Examples: Native Plant Communities Donaldson Run Park -

Arlington County, Virginia

Arlington County, Virginia Fiscal Year 2013 Annual Stormwater Management Program Report VPDES Permit No. VA0088579 2002 – 2007 Permit Cycle Submitted September 30, 2013 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 3 Watershed management overview ............................................................................................ 3 Key accomplishments ............................................................................................................... 4 Program management .............................................................................................................. 6 2 STATUS OF THE STORM WATER MANAGEMENT PROGRAM ............................. 8 A. STRUCTURAL AND SOURCE CONTROLS............................................................................... 9 B. AREAS OF NEW DEVELOPMENT AND SIGNIFICANT REDEVELOPMENT ................................ 9 Stormwater controls for new development/redevelopment ...................................................... 9 Erosion and sediment control during construction ................................................................ 10 Green building programs ....................................................................................................... 10 C. ROADWAYS ...................................................................................................................... 11 Street sweeping ...................................................................................................................... -

Corridor Analysis for the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia

Corridor Analysis For The Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail In Northern Virginia June 2011 Acknowledgements The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this report: Don Briggs, Superintendent of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail for the National Park Service; Liz Cronauer, Fairfax County Park Authority; Mike DePue, Prince William Park Authority; Bill Ference, City of Leesburg Park Director; Yon Lambert, City of Alexandria Department of Transportation; Ursula Lemanski, Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program for the National Park Service; Mark Novak, Loudoun County Park Authority; Patti Pakkala, Prince William County Park Authority; Kate Rudacille, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; Jennifer Wampler, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation; and Greg Weiler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The report is an NVRC staff product, supported with funds provided through a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Region National Park Service. Any assessments, conclusions, or recommendations contained in this report represent the results of the NVRC staff’s technical investigation and do not represent policy positions of the Northern Virginia Regional Commission unless so stated in an adopted resolution of said Commission. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the jurisdictions, the National Park Service, or any of its sub agencies. Funding for this report was through a cooperative agreement with The National Park Service Report prepared by: Debbie Spiliotopoulos, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission with assistance from Samantha Kinzer, Environmental Planner The Northern Virginia Regional Commission 3060 Williams Drive, Suite 510 Fairfax, VA 22031 703.642.0700 www.novaregion.org Page 2 Northern Virginia Regional Commission As of May 2011 Chairman Hon. -

Under the Ice Frogs and Turtles Sometimes Become Active Under the Ice and Can Be Seen Moving Slowly About

WINTER 2015-2016 CHECK OUT OUR GREAT NATURE PROGRAMS! REGISTRATION BEGINS November 16, 2015 WHAT’S HAPPENING Sign up to receive THE SNAG and to find other information about our nature and conservation programs at http://parks.arlingtonva.us GULF BRANCH NATURE CENTER LONG BRANCH NATURE CENTER FORT C.F. SMITH PARK 3608 Military Road 625 S. Carlin Springs Road 2411 N. 24th St. Arlington, VA 22207 Arlington, VA 22204 Arlington, VA 22207 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 703-228-3403 703-228-6535 703-228-7033 Some frogs hibernate at the bottom of ponds, breathing through their skin. Frogs usually lie on the bottom rather than dig into the oxygen-poor mud because they require more oxygen than the mud can supply. Painted, snapping, and other native aquatic turtles also breathe through their skin during hibernation, but maintain a much lower metabolism than frogs. Consequently, they need less oxygen and can afford to bury themselves in the mud. In more northern latitudes, where ice can cover ponds and lakes for months and oxygen can become depleted, turtles have another trick up their shell. They can switch to anaerobic respiration, meaning respiration without oxygen. They can keep this up for weeks or even months! Under the Ice Frogs and turtles sometimes become active under the ice and can be seen moving slowly about. You might also see fish and aquatic insects such as water boatmen and predacious diving beetles. Check it out — under the ice! n the summer ponds are obviously lively places. Frogs sit along the edge or float in the water while turtles bask on logs and rocks. -

Text Statement, "Parkways of the National Capital Region, 1913 to 1965," Is Attached to This Document

f/o NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 8/93} United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form INTERA&NCV RESOURCES DIVISION I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts, See i Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item b II i te b *r the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_____________________________________________________ historic name: George Washington Memorial Parkway____________________________________ other names/site number: N/A________________________________________________ 2. Location______________________________ Wq^hinntnn Mpmong] Pgtrkw^V_________________________________________________________ street & number: Turkey Run Park____________________________________[ ] not for publication city or town: McLean, VA vicinity state: Maryland. Virginia, DC counties: Montgomery, Arlington, Fairfax, DC: code: 031, 013, 059, 001 zip code: 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ «""{rneets [ ] does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered signifies*]* [ ^naiionally [ ] statewide [ ] locally. -

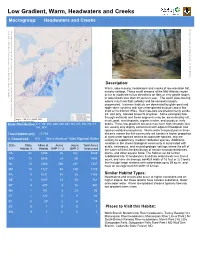

Low Gradient, Warm, Headwaters and Creeks Macrogroup: Headwaters and Creeks

Low Gradient, Warm, Headwaters and Creeks Macrogroup: Headwaters and Creeks Small Creek in Maryland, © MD DNR Ecologist or State Fish Game Agency for more information about this habitat. This map is based on a model and has had little field-checking. Contact your State Natural Heritage Description: Warm, slow-moving, headwaters and creeks of low-elevation flat, marshy settings. These small streams of the Mid-Atlantic region occur at moderate to low elevations on flats or very gentle slopes in watersheds less than 39 sq.mi in size. The warm slow-moving waters may have high turbidity and be somewhat poorly oxygenated. Instream habitats are dominated by glide-pool and ripple-dune systems with runs interspersed by pools and a few short or no distinct riffles. Bed materials are predominenly sands, silt, and only isolated amounts of gravel. Some examples flow through wetlands and these segments may be dominated by silt, Source: 1:100k NHD+ (USGS 2006), >= 1 sq.mi. drainage area muck, peat, marl deposits, organic matter, and woody or leafy State Distribution:CT, DE, DC, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, debris. These low-gradiient streams may have high sinuosity, but VA, WV are usually only slightly entrenched with adjacent floodplain and riparian wetland ecosystems. Warm water temperatures in these Total Habitat (mi): 17,704 streams means the fish community will contain a higher proportion of warmwater species relative to coolwater species, and are % Conserved: 9.0 Unit = Acres of 100m Riparian Buffer unlikely to support any resident coldwater species. Additional variation in the stream biological community is associated with State State Miles of Acres Acres Total Acres acidic, calcareous, and neutral geologic settings where the pH of Habitat % Habitat GAP 1 - 2 GAP 3 Unsecured the water will limit the distribution of certain macroinvertebrates, VA 42 7455 26 162 5449 plants, and other aquatic biota.