Sewickley Creek Watershed Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTICES Obtain a Permit from the Department Prior to Cultivating, DEPARTMENT of AGRICULTURE Propagating, Growing Or Processing Hemp

1831 NOTICES obtain a permit from the Department prior to cultivating, DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE propagating, growing or processing hemp. General Permit Standards and Requirements for K. Hemp has been designated a controlled plant in Hemp Pennsylvania and its propagation, cultivation, testing, transportation, warehousing and storage, processing, dis- Recitals. tribution and sale is of a statewide concern. This Notice amends and replaces the previous Notice L. This General Permit establishes rules and require- ‘‘General Permit Standards and Requirements for Hemp’’ ments for the distribution and sale of hemp planting published in the December 5, 2020 Pennsylvania Bulletin materials, and for the propagation, cultivation, testing, (50 Pa.B. 6906, Saturday, December 5, 2020). transportation, warehousing, storage, and processing of hemp as authorized by the Act. A. The Act relating to Controlled Plants and Noxious Weeds (‘‘Act’’) (3 Pa.C.S.A. § 1501 et seq.) authorizes the M. This General Permit does not and may not abrogate Department of Agriculture (Department) through the the provisions of the act related to industrial hemp Controlled Plant and Noxious Weed Committee (Commit- research, at 3 Pa.C.S.A. §§ 701—710, including, permit- tee) to establish a controlled plant list and to add plants ted growers must still submit fingerprints to the Pennsyl- to or remove plants from the controlled plant list vania State Police for the purpose of obtaining criminal (3 Pa.C.S.A. § 1511(b)(3)(ii)(iii)). history record checks. The Pennsylvania State Police or its authorized agent shall submit the fingerprints to the B. The Act provides for publication of the noxious weed Federal Bureau of Investigation for the purpose of verify- and the controlled plant list and additions or removals or ing the identity of the applicant and obtaining a current changes thereto to be published as a notice in the record of any criminal arrests and convictions. -

Stormwater Management Plan Phase 1

Westmoreland County Department of Planning and Development Greensburg, Pennsylvania Act 167 Scope of Study for Westmoreland County Stormwater Management Plan June 2010 © PHASE 1 – SCOPE OF STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3 Purpose6 ................................................................................................................... 3 Stormwater7 Runoff Problems and Solutions ........................................................ 3 Pennsylvania8 Storm Water Management Act (Act 167) ................................... 4 9 Act 167 Planning for Westmoreland County ...................................................... 5 Plan1 Benefits ........................................................................................................... 6 Stormwater1 Management Planning Approach ................................................. 7 Previous1 County Stormwater Management Planning and Related Planning Efforts ................................................................................................................................. 8 II. GENERAL COUNTY DESCRIPTION ........................................................................... 9 Political1 Jurisdictions .............................................................................................. 9 NPDES1 Phase 2 Involvement ................................................................................. 9 General1 Development Patterns ........................................................................ -

April 17, 2004 (Pages 2049-2154)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 34 (2004) Repository 4-17-2004 April 17, 2004 (Pages 2049-2154) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2004 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "April 17, 2004 (Pages 2049-2154)" (2004). Volume 34 (2004). 16. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2004/16 This April is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 34 (2004) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 34 Number 16 Saturday, April 17, 2004 • Harrisburg, Pa. Pages 2049—2154 Agencies in this issue: The Governor The General Assembly The Courts Delaware River Basin Commission Department of Banking Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Education Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Labor and Industry Department of Public Welfare Department of Transportation Environmental Quality Board Executive Board Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Legislative Reference Bureau Liquor Control Board Milk Marketing Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Regional Port Authority Public School Employees’ Retirement Board Detailed list of contents appears inside. PRINTED ON 100% RECYCLED PAPER Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): No. 353, April 2004 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN reau, 647 Main Capitol Building, State & Third Streets, (ISSN 0162-2137) Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publication and effectiveness of Com- monwealth Documents). -

SEWICKLEY CREEK TMDL Westmoreland County

DRAFT SEWICKLEY CREEK TMDL Westmoreland County For Mine Drainage Affected Segments Prepared by: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection December 31, 2008 1 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................................................. 3 Directions to the Sewickley Creek.............................................................................................. 3 Watershed Characteristics........................................................................................................... 3 Segments addressed in this TMDL............................................................................................. 4 Clean Water Act Requirements .................................................................................................. 4 Section 303(d) Listing Process ................................................................................................... 5 Basic Steps for Determining a TMDL........................................................................................ 6 AMD Methodology..................................................................................................................... 6 TMDL Endpoints........................................................................................................................ 8 TMDL Elements (WLA, LA, MOS) .......................................................................................... 9 Allocation Summary.................................................................................................................. -

Code of Federal Regulations GPO Access

4±4±97 Friday Vol. 62 No. 65 April 4, 1997 Pages 16053±16464 Briefings on how to use the Federal Register For information on briefings in Washington, DC, see announcement on the inside cover of this issue Now Available Online Code of Federal Regulations via GPO Access (Selected Volumes) Free, easy, online access to selected Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) volumes is now available via GPO Access, a service of the United States Government Printing Office (GPO). CFR titles will be added to GPO Access incrementally throughout calendar years 1996 and 1997 until a complete set is available. GPO is taking steps so that the online and printed versions of the CFR will be released concurrently. The CFR and Federal Register on GPO Access, are the official online editions authorized by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register. New titles and/or volumes will be added to this online service as they become available. http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr For additional information on GPO Access products, services and access methods, see page II or contact the GPO Access User Support Team via: ★ Phone: toll-free: 1-888-293-6498 ★ Email: [email protected] federal register 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 65 / Friday, April 4, 1997 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES PUBLIC Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, General online information 202±512±1530 (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), 1±888±293±6498 by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Single copies/back copies: Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Paper or fiche 512±1800 Register Act (49 Stat. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

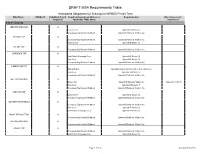

DRAFT MS4 Requirements Table

DRAFT MS4 Requirements Table Anticipated Obligations for Subsequent NPDES Permit Term MS4 Name NPDES ID Individual Permit Impaired Downstream Waters or Requirement(s) Other Cause(s) of Required? Applicable TMDL Name Impairment Adams County ABBOTTSTOWN BORO No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) BERWICK TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) BUTLER TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CONEWAGO TWP No South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CUMBERLAND TWP No Willoughby Run Appendix E-Organic Enrichment/Low D.O., Siltation (5) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) GETTYSBURG BORO No Stevens Run Appendix E-Nutrients, Siltation (5) Unknown Toxicity (5) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) HAMILTON TWP No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) MCSHERRYSTOWN BORO No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) MOUNT PLEASANT TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) NEW OXFORD BORO No -

Southwestern Pennsylvania Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permittees

Southwestern Pennsylvania Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permittees ALLEGHENY COUNTY Municipality Stormwater Watershed(s) River Watershed(s) Aleppo Twp. Ohio River Ohio River Avalon Borough Ohio River Ohio River Baldwin Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Peters Creek Monongahela River Sawmill Run Ohio River Baldwin Township Sawmill Run Ohio River Bellevue Borough Ohio River Ohio River Ben Avon Borough Big Sewickley Creek Ohio River Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Bethel Park Borough Peters Creek Monongahela River Chartiers Creek Ohio River Sawmill Run Ohio River Blawnox Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Brackenridge Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Bull Creek Allegheny River Braddock Hills Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Turtle Creek Monongahela River Bradford Woods Pine Run Allegheny River Borough Connoquenessing Creek Beaver River Big Sewickley Creek Ohio River Brentwood Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Sawmill Run Ohio River Bridgeville Borough Chartiers Creek Ohio River Carnegie Borough Chartiers Creek Ohio River Castle Shannon Chartiers Creek Ohio River Borough Sawmill Run Ohio River ALLEGHENY COUNTY Municipality Stormwater Watershed(s) River Watershed(s) Cheswick Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Churchill Borough Turtle Creek Monongahela River Clairton City Monongahela River Monongahela River Peters Creek Monongahela River Collier Township Chartiers Creek Ohio River Robinson Run Ohio River Coraopolis Borough Montour Run Ohio River Ohio River Ohio River Crescent Township -

February 14, 2004 (Pages 819-938)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 34 (2004) Repository 2-14-2004 February 14, 2004 (Pages 819-938) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2004 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "February 14, 2004 (Pages 819-938)" (2004). Volume 34 (2004). 7. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2004/7 This February is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 34 (2004) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 34 Number 7 Saturday, February 14, 2004 • Harrisburg, Pa. Pages 819—938 Agencies in this issue: The Governor The General Assembly The Courts Department of Agriculture Department of Banking Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Education Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Labor and Industry Department of Revenue Department of Transportation Environmental Hearing Board Executive Board Fish and Boat Commission Historical and Museum Commission Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Pennsylvania Municipal Retirement Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Public School Employees’ Retirement Board State Board of Nursing State Police Detailed list of contents appears inside. PRINTED ON 100% RECYCLED PAPER Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): No. 351, February 2004 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN reau, 647 Main Capitol Building, State & Third Streets, (ISSN 0162-2137) Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publication and effectiveness of Com- monwealth Documents). -

October 11, 2003 (Pages 5061-5162)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 33 (2003) Repository 10-11-2003 October 11, 2003 (Pages 5061-5162) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2003 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "October 11, 2003 (Pages 5061-5162)" (2003). Volume 33 (2003). 41. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2003/41 This October is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 33 (2003) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 33 Number 41 Saturday, October 11, 2003 • Harrisburg, Pa. Pages 5061—5162 Agencies in this issue: The Governor The General Assembly The Courts Delaware River Basin Commission Department of Agriculture Department of Banking Department of Community and Economic Development Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Education Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Revenue Environmental Hearing Board Executive Board Fish and Boat Commission Housing Finance Agency Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Liquor Control Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Public School Employees’ Retirement Board Detailed list of contents appears inside. PRINTED ON 100% RECYCLED PAPER Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): No. 347, October 2003 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN reau, 647 Main Capitol Building, State & Third Streets, (ISSN 0162-2137) Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publication and effectiveness of Com- monwealth Documents). -

Volume 33 Number 29 Saturday, July 19, 2003 • Harrisburg, Pa. Pages 3467—3590

Volume 33 Number 29 Saturday, July 19, 2003 • Harrisburg, Pa. Pages 3467—3590 Agencies in this issue: The Governor The General Assembly The Courts Department of Banking Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Revenue Department of State Executive Board Fish and Boat Commission Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Legislative Reference Bureau Milk Marketing Board Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Regional Port Authority Securities Commission Turnpike Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. PRINTED ON 100% RECYCLED PAPER Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): No. 344, July 2003 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- reau, 647 Main Capitol Building, State & Third Streets, (ISSN 0162-2137) Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publication and effectiveness of Com- monwealth Documents). Subscription rate $82.00 per year, postpaid to points in the United States. Individual copies $2.50. Checks for subscriptions and individual copies should be made payable to ‘‘Fry Communications, Inc.’’ Postmaster send address changes to: Periodicals postage paid at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Orders for subscriptions and other circulation matters FRY COMMUNICATIONS should be sent to: Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin 800 W. Church Rd. Fry Communications, Inc. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055-3198 Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin (717) 766-0211 ext. 2340 800 W. Church Rd. (800) 334-1429 ext. 2340 (toll free, out-of-State) Mechanicsburg, PA 17055-3198 (800) 524-3232 ext. -

Westmoreland County Natural Heritage Inventory, 1998

WESTMORELAND COUNTY NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY Prepared for: The Westmoreland County Department of Planning and Development 601 Courthouse Square Greensburg, PA 15601 Prepared by: Western Pennsylvania Conservancy 209 Fourth Ave. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222 September 1998 This project was funded by the Keystone Recreation Park and Conservation Fund Grant Program administered by the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation and the Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation. Printed on recycled paper PREFACE The Westmoreland County Natural Heritage Inventory identifies and maps Westmoreland County’s most significant natural places. The study investigated plant and animal species and natural communities that are unique or uncommon in the county; it also explored areas important for general wildlife habitat and scientific study. The inventory does not confer protection on any of the areas listed here. It is, however, a tool for informed and responsible decision-making. Public and private organizations may use the inventory to guide land acquisition and conservation decisions. Local municipalities and the County may use it to help with comprehensive planning, zoning and the review of development proposals. Developers, utility companies and government agencies alike may benefit from access to this environmental information prior to the creation of detailed development plans. Although the inventory was conducted using a tested and proven methodology, it is best viewed as a preliminary report rather than the final word on the subject of Westmoreland County’s natural heritage. Further investigations could potentially uncover previously unidentified Natural Heritage Areas. Likewise, in-depth investigations of sites listed in this report could reveal features of further or greater significance than have been documented here.