Australian Rules Football Cheer Squads of the Eighties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channel 7'S Return to WAFL

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WAFL ROUND 1 MARCH 20, 2015 $3.00 Sharks and Royals SHOWCASE ChannelChannel 7’s7’s returnreturn toto WAFLWAFL Subiaco team poster Collectables Entertainment THE TLC GROUP THE LIFTING COMPANY www.TheLiftingCompany.com.au Lifting,There Rigging is andAlways Height a Safety Solution Specialists Specialists in Lifting, Rigging and Height Safety Equipment TLC SURFACE TREATMENT www.TLCSurfaceTreatment.com.au Protective Coating Applicators Perth’s Industrial Spray Painting & Sandblasting Specialists TLC FABRICATION www.TheLiftingCompany.com.au Engineering, Design & Fabrication THE LIFTING COMPANY Professionals in Fabrication www.TheLiftingCompany.com.au There is Always a Solution Proud sponsors of the Perth Demons Football Club Ph: (08) 9353 4333 www.theTLCgroup.com.au CONTENTS 3 Every Week 6 ..................Collectables 7 ..................Tipping 7 ..................Tweets of the Week 20-22 .......WAFC 23 ...............Club Notes 24 ...............Stats 25 ...............Scoreboards and ladders 26 ...............Fixtures Features 4-5 .............WAFL back on Channel 7 8 ..................Entertainment 14-15 ...........Subiaco team poster Game time 9 ..................Game previews 10-11 .............South Fremantle v West Perth 12-13 ...........Swan Districts v Perth 16-17 ...........Subiaco v Claremont 18-19 ...........East Fremantle v East Perth CONTENTS 4 Channelbiggest 7 again provide Publisher This publication is proudly produced for the WA Football Commission by LEADING into the They take back the broadcast rights from the Media Tonic. 1978 WAFL season, ABC who were the stand along broadcasters of the Phone 9388 7844 WAFL from 1987 up until the end of last season. Fax 9388 7866 the biggest pre-season Channel 7 first broadcast the WAFL in 1961. Sales: [email protected] football story involved Editor They aired about a quarter of a match in the Tracey Lewis Channel 7 Perth. -

What's Inside?

What’s Inside? 2017 YEARLY PLANNER PLAYERS EVERY ISSUE DAY ROUND EVENT GAME LOCATION TIME Sat, 18th Round 1 EFFC v CFC East Fremantle Oval 2.15pm MEET MESSAGE FROM Sat, 25th Round 2 CFC BYE 8 THE PLAYERS 4 THE PRESIDENT MARCH Sat, 1st Round 3 PFC v CFC Lathlain Park 1.40pm *7MATE WINMAR MAKING MESSAGE FROM 16 Fri, 7th Round 4 Fathering Project EPFC v CFC Leederville Oval 7.10pm 17 5 THE CEO HIS THIRD START Fri, 14th Round 5 Easter SFFC v CFC Fremantle Oval 4.15pm APRIL Laurie, the MESSAGE FROM HARRIS HAS THE MIDAS Sat, 22nd Round 6 ANZAC CFC v SFC East Fremantle Oval 2.15pm 18 drought buster 6 THE COACH TOUCH Sat, 29th Round 7 SDFC v CFC Steele Blue Oval 2.15pm LEE HAS EYES DISTRICT APRIL Sat, 6th Round 8 CFC v PTFC Fremantle Oval 2.15pm 19 ON A FLAG 24 SCHOOL CLINIC Sat, 13th Round 9 CFC v PFC Fremantle Oval 7.10pm MAY Sat, 20th Round 10 Men’s Health WPFC v CFC HBF Arena Joondalup 2.15pm CLAREMONT MORABITO HOPING 25 WOMEN’S Sat, 27th State Round CFC BYE 20 FOR A MAY START 13 FOOTBALL NEWS Sat, 3rd Round 11 WA Round CFC BYE Sat, 10th Opening Day 1.45pm LE FANU ABOUT OUR 21 CONTINUES HIS Sat, 10th Round 12 Count me in Round CFC v EFFC Claremont Oval 2.15pm 26 2017 SPONSORS FOOTBALL MURPHY REMAINS AT THE JUNE Sat, 17th Round 13 CFC v SDFC Claremont Oval 2.15pm JOURNEY HELM COACHES Sat, 24th Proudie’s Day Sat, 24th Round 14 CFC v WPFC Claremont Oval 2.15pm CLUB AWARDS BRADLEY’S Sat, 1st Round 15 PTFC v CFC Bendigo Bank Stadium 2.15pm 7 SAGE ADVICE Sat, 8th Round 16 NAIDOC Round CFC v SFFC Claremont Oval 1.40pm *7MATE ED & SHIRLEY Sat,15th Round 17 SFC v CFC Esperance 2.15pm JULY 23 HONOURED CONDON AND WHITE Sat, 22nd Round 18 CFC BYE 12 ARE ON BOARD 22 Sat, 29th Round 19 CFC v EPFC Claremont Oval 2.15pm KEN CASELLAS Sat, 5th Round 20 PFC v CFC Lathlain Park 2.15pm 14 TALKS TO THE CLAREMONT SALUTES A Sat, 12th CFC Ladies Day 1.40pm *7MATE COACHES. -

AFL D Contents

Powering a sporting nation: Rooftop solar potential for AFL d Contents INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................................1 AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE ...................................................................................... 3 AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL TEAMS SUMMARY RESULTS ........................4 Adelaide Football Club .............................................................................................................7 Brisbane Lions Football Club ................................................................................................ 8 Carlton Football Club ................................................................................................................ 9 Collingwood Football Club .................................................................................................. 10 Essendon Football Club ...........................................................................................................11 Fremantle Football Club .........................................................................................................12 Geelong Football Club .............................................................................................................13 Gold Coast Suns ..........................................................................................................................14 Greater Western Sydney Giants .........................................................................................16 -

The Heart Still Beats True

Issue 5, July 2018 HEARTBEAT A newsletter for past players and officials of the West Perth Football Club The heart still beats true Inside this Issue Page Welcome 1 Where Are They Now? 2 Heading West 4 1957 team flashback 8 Mel is recognised 9 Welcome to the July 2018 those past players who Father and son in focus 12 issue of HeartBeat. may have sired future My first game 14 club champions, we take a In this edition, we catch look at the father-son and Obituaries 16 up with former captain- grandfather -grandson coach Bob Spargo and rules as they stand. players Brendon Fewster and Howard Collinge. Finally, if you back yourself to name the We’ll also look back on a player in the above big night at the Australian photograph, feel free to Does your heart beat true? Football Hall of Fame for drop us a line at Mel Whinnen and, for all [email protected] career, and recognise other past players who have passed away more recently. Where are they now? – Howard Collinge I started my junior football in the West Perth zone and landed in the Falcons Colts at age sixteen, alongside a bunch of skinny talented guys like Craig Turley, Dean Laidley, Paul Mifka and Darren Bewick. I progressed to the Reserves to play alongside great athletes like John Gastev, Peter Cutler and James Waddell. They all went on to great careers at West Perth and beyond. I took a different path. I was a Falcons fan, for sure. Les Fong was a secret hero of mine for many reasons. -

Reporter Stirling Vincent 10062021

Thursday, June 10, 2021 perthnow.com.au/community-news Council staff bid to stop ASHESmemorials to loved ones TEST Kristie Lim she wanted more time to did not have the informa- discuss whether ashes tion on-hand at the meet- CITY of Vincent officers could be allowed to be ing. want to stop people scat- scattered in public places. Cr Ashley Wallace said tering the ashes of their “In Wales, they have for- more time was needed to loved ones on council ests where you can put consider whether a ban on land. your loved one in an orga- scattering of ashes would The proposal is part of a nic cardboard box and be a good idea or not. review of the City’s bury them in a forest Infrastructure and memorials in public plac- where there are no environment executive es and reserves policy. plaques,” she said. director Andrew Murphy Council officers say “I do think that our per- said some people might people can instead use the ceptions of what we do not like ashes being scat- Metropolitan Cemeteries with our loved ones are tered in public areas. Board’s “specialised facil- changing and if it is orga- The policy will be dealt Turtley awesome ities”. nic and not upsetting the with by the council before However the council environment, I don’t have December 31. Ten gorgeous baby turtles have been has pushed back, voting at a problem with it.” The City of Bayswater released into a suburban lake. its May 18 meeting to defer She also asked officers has a memorial seat policy Picture: Catherine advertising the proposed about whether there were which does not allow ash- FULL STORY P3 Ehrhardt policy for comment. -

President's Welcome Since Inception in 1934, the Swan Districts Football

1934—2016 HALL of FAME Index Swan Districts Football Club: Hall of Fame Bob Bryant � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2 Stan Nowotny � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 20 Ted Holdsworth � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3 Ron Boucher � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 21 Lal Mosey � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 Keith Narkle � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 22 Tom Moiler � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Garry Sidebottom � � � � � � � � � � � 23 John (Jack) Murray � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Don Langsford � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 24 Joe Pearce � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 7 John Todd � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 25 Duggan Anderson � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 Don Holmes � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 26 Tim Barker � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9 Travis Edmonds � � � � � � � � � � � � � 27 John Cooper � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 Ron Jose � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Joe Lawson � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 Keith Slater � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 13 Stan Moses � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 14 Ken Bagley � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 15 Fred Castledine � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 Tony Nesbit � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 Haydn Bunton � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 18 28 Bill Walker � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 19 President’s Welcome Peter Hodyl Since inception in 1934, the Swan Districts Football Club has been etched deep in Western Australian Football history. Significant achievements and events highlighted by Premierships, Sandover Medals and breathtaking displays by our champions have resulted -

S E a S O N G U I

21 2021 20 21 SEASON GUIDE 21 2021 2021 2021 20 2 | 2021 SEASON GUIDE 2021 FIXTURES ROUND DATE VS LOCATION TIME 1 Sat, April 3 Swan Districts Steel Blue Oval 2:10pm 2 Sat, April 10 South Fremantle Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 3 Sat, April 17 Perth Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 4 Sat, April 24 Peel Thunder David Grays Arena 2:10pm 5 Sat, May 1 West Perth Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 6 Sat, May 8 Subiaco Leederville Oval 2:10pm 7 Sat, May 22 East Fremantle New Choice Homes Park 2:10pm 8 Sat, May 29 East Perth Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 9 Sat, June 5 West Coast Revo Fitness Stadium 12:10pm 10 Sat, June12 Peel Thunder Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 11 BYE 12 Sat, June 26 West Perth Provident Financial Oval 2:10pm 13 Sat, July 3 Swan Districts Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 14 Sat, July 10 South Fremantle Fremantle Community Bank 2:10pm Oval 15 Sat, July 17 East Fremantle Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 16 BYE 17 Sun, August 1 East Perth Leederville Oval 2:10pm 18 Sat, August 7 Subiaco Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm 19 Sat, August 14 Perth Mineral Resources Park 2:10pm 20 Sat, August 21 West Coast Revo Fitness Stadium 2:10pm TBC WAFL FINALS TBC GRAND FINAL CLAREMONTFC.COM.AU | 3 As a club let’s all be COMMITTED to the 1% er’s that make big things happen. “The little things,” are the cru- cial details that determine the outcomes of life. -

Use of Lathlain Park for Playing of Competitive Football Matches

12.4 Use of Lathlain Park for playing of competitive football matches Location Lathlain Reporting officer Robert Cruickshank Responsible officer Robert Cruickshank Voting requirement Simple majority Attachments 1. West Coast Eagles - Development Application - Engagement and Communication Overview [12.4.1 - 5 pages] Recommendation That Council: 1. Notes the Communications and Engagement Overview contained at Attachment 1, to be implemented upon the receipt of a development application from Indian Pacific Limited (West Coast Eagles Football Club) for the playing of competitive football matches at Lathlain Park. 2. Requests that the Chief Executive Officer presents a further report to Council following the community consultation period to consider the public submissions received and its recommendation to the WAPC on the development application. 3. Notes the legal advice received. Purpose The purpose of this report is to note the legal advice and advice from the Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC) on the playing of competitive football matches at Lathlain Park, and for Council to note the intended actions arising from this. In brief As a consequence of the 2020 Marsh Community Series preseason competition AFL game fixture at Mineral Resources Park on Thursday 27th February 2020, queries were raised by Elected Members and members of the community relating to the playing of competitive AFL football matches by the West Coast Eagles within their lease area at Lathlain Park (Mineral Resources Park, MRP). As background to this, advice from the West Coast Eagles prior to lease commencement, was that no AFL matches would be played at Lathlain Park. Legal advice was subsequently sought by the Town in respect to the (Indian Pacific Limited) lease permitted use provisions. -

Lives & Breathes His Way To

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WAFL ROUND 3 AprIL 1, 2017 $3.00 Jones lives300 & breathes games his way to » Game previews » Entertainment » Collectables CONTENTS 3 Every Week 6 Collectables 7 Tipping 7 Tweets of the Week 20-22 WAFC 23 Club Notes 25 Stats 26 Scoreboards and ladders 27 Fixtures Features 4-5 Jones lives and breathes his way to 300 games 8 Entertainment Game time 9 Game previews 10-11 Perth v Claremont 12-13 Peel v South Fremantle 14-15 East Perth v Swan Districts 16-17 West Perth v Subiaco 18 West Coast v St Kilda 18 CONTENTS Port Adelaide v Fremantle 4 Jones lives and300 breathes his way to Publisher games This publication is proudly produced for the WA Football Commission by Media Tonic. Phone 9388 7844 Fax 9388 7866 Sales: [email protected] Editor Tracey Lewis Email: [email protected] Photography Andrew Ritchie, Duncan Watkinson, Showcase photgraphix Design/Typesetting Jacqueline Holland Direction Design and Print Printing Data Documents www.datadocuments.com.au Cover Clint Jones - by Duncan Watkinson The Football Budget is printed on Gloss 90gsm paper, which is sourced from a sustainably managed forest and uses manufacturing processes of the highest environmental standards. Bouncedown is printed by an Environmental Accredited printer. The magazine is 100% recyclable. WAFL admission prices $15 – Adult* $12 – Concession* Free – Children 15 and under *Includes a copy of Football Budget Find us on Copyright © No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system without the permission of the publisher. Opinions expressed in the Football Budget are not necessarily those of the WAFC. -

BEATTY PARK LEISURE CENTRE CONSERVATION PLAN Vincent

BEATTY PARK LEISURE CENTRE CONSERVATION PLAN Vincent Street, North Perth September 2007 for the Town of Vincent Job No. 04183 With Robin Chinnery, Historian Cover Image: Original entrance to the Beatty Park Leisure Centre. Image courtesy Town of Vincent. Page i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Town of Vincent commissioned this Conservation Plan to assist them in conserving and developing the Beatty Park Leisure Centre to assure its future. Apart from being a very important part of the Town and State’s heritage, it is the Town of Vincent’s most significant trading enterprise. A separate conservation plan will be commissioned for the remainder of the park. The pool and spectator stands were developed in 1962 for the VII th British Empire and Commonwealth Games and substantial additions were made in 1993-4, changing the focus of the venue towards leisure rather than a venue for training elite athletes. The whole of the place is a busy working facility and there is a need to upgrade the 1962 facilities in particular. The Town is considering a major refurbishment and upgrade of the stands and pool area to meet with contemporary standards and expectations, and this prospect precipitated the need for a conservation plan. The 1962 structure is under- utilised with, for example, only a fraction of the stand seating being used, and there are some re-planning possibilities to consider to make the operation as a whole perform better, which may give rise to the consideration of alternative uses for some of the spaces under the 1962 stands. As the place is included in the Register of Heritage Places and registered as Beatty Park and Beatty Park Leisure Centre , the Conservation Plan is intended to assist the Town of Vincent and the Heritage Council of Western Australia to assess the impact of proposed change on cultural heritage values and the conservation of the place. -

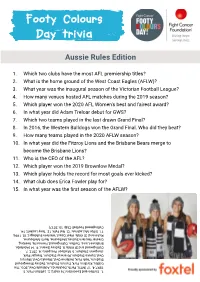

Aussie Rules Edition

Footy Colours Day trivia Aussie Rules Edition 1. Which two clubs have the most AFL premiership titles? 2. What is the home ground of the West Coast Eagles (AFLW)? 3. What year was the inaugural season of the Victorian Football League? 4. How many venues hosted AFL matches during the 2019 season? 5. Which player won the 2020 AFL Women’s best and fairest award? 6. In what year did Adam Treloar debut for GWS? 7. Which two teams played in the last drawn Grand Final? 8. In 2016, the Western Bulldogs won the Grand Final. Who did they beat? 9. How many teams played in the 2020 AFLW season? 10. In what year did the Fitzroy Lions and the Brisbane Bears merge to become the Brisbane Lions? 11. Who is the CEO of the AFL? 12. Which player won the 2019 Brownlow Medal? 13. Which player holds the record for most goals ever kicked? 14. What club does Erica Fowler play for? 15. In what year was the first season of the AFLW? Collingwood Football Club; 15. 2017) 15. Club; Football Collingwood 11. Gillon McLachlan; 12. Nat Fyfe; 13. Tony Lockett; 14. 14. Lockett; Tony 13. Fyfe; Nat 12. McLachlan; Gillon 11. Richmond, St Kilda, West Coast, Western Bulldogs); 10. 1996; 1996; 10. Bulldogs); Western Coast, West Kilda, St Richmond, Greater Western Sydney, Melbourne, North Melbourne, Melbourne, North Melbourne, Sydney, Western Greater Brisbane Lions, Carlton, Collingwood, Fremantle, Geelong, Geelong, Fremantle, Collingwood, Carlton, Lions, Brisbane Collingwood and St Kilda; 8. Sydney Swans; 9. 14 (Adelaide, (Adelaide, 14 9. Swans; Sydney 8. -

25968 Dsr Ar

2004/2005 Annual Report Hon. Mark McGowan BA LLB MLA Minister for Sport and Recreation In accordance with Section 62 of the Financial Administration and Audit Act 1985, I hereby submit for your information and presentation to Parliament the annual report of the Department of Sport and Recreation for the period 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2005. Ron Alexander Director General Department of Sport and Recreation 246 Vincent Street LEEDERVILLE WA 6007 2 Department of Sport and Recreation • 2004/2005 Annual Report Contents Highlights ........................................................................ 4 Corporate Overview ......................................................... 5 Director General’s Report ............................................... 12 Sport and Recreation Portfolio Structure ......................... 13 The Year in Review ......................................................... 14 Business Management, Legislation and Compliance ....... 36 Statutory Reporting ........................................................ 40 Corporate Legislation and Compliance ........................... 45 Sponsors ....................................................................... 46 Grants to Sport and Recreation Organisations ................. 47 Community Sporting and Recreation Facilities Fund Approvals (CSRFF) ................................................ 55 Independent Audit Opinion – Financial Statements .......... 61 Financial Statements ...................................................... 62 Independent Audit Opinion – Performance