Open Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standing Committee of Tynwald on Emoluments First Report for the Session 2020-21 Provision for an Independent Pay Body, and Other Matters

PP 2021/0014 STANDING COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON EMOLUMENTS FIRST REPORT FOR THE SESSION 2020-2021 PROVISION FOR AN INDEPENDENT PAY BODY, AND OTHER MATTERS STANDING COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON EMOLUMENTS FIRST REPORT FOR THE SESSION 2020-21 PROVISION FOR AN INDEPENDENT PAY BODY, AND OTHER MATTERS 1. There shall be a Standing Committee of the Court on Emoluments. 2. The Committee shall be chaired by the Speaker of the House of Keys and composed of the Members of the Management and Members’ Standards Committee of the Keys, and three Members of the Council elected by that Branch. 3. The Committee shall - (i) consider and report to Tynwald on - (a) the emoluments of H E Lieutenant Governor, their Honours the First and Second Deemsters and the Judge of Appeal, H M Attorney General, the High Bailiff, the Deputy High Bailiff and the Clerk of Tynwald; (b) the Tynwald Membership Pension Scheme; and (c) in addition to its consultative functions set out in paragraph 8.3 (ii) and as it thinks fit, the emoluments of Members of Tynwald; (iii) carry out its consultative functions under section 6(3) of the Payments of Members’ Expenses Act 1989, as the body designated by the Payment Of Members' Expenses (Designation of Consultative Body) Order 1989. The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald include those conferred by the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973, the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984 and by the Standing Orders of Tynwald Court. Committee Membership The Hon J P Watterson SHK (Rushen) (Chairman) Mr D J Ashford MHK (Douglas East) Miss T M August-Hanson MLC Ms J M Edge MHK (Onchan) Mr R W Henderson MLC Mrs M M Maska MLC Mr C P Robertshaw MHK (Douglas East) Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, IM1 3PW (Tel: 01624 685520) or may be consulted at www.tynwald.org.im. -

Duties of Advocates to the High Court of Justice of the Isle of Man

NOTES IN RESPECT OF TALKS TO TRAINEE MANX ADVOCATES (Talk at 5pm on 16 October 2017) DUTIES OF ADVOCATES TO THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE ISLE OF MAN C O N T E N T S Pages The Advocate’s Oath ……..………………………………………………………………………… 1 The Manx legal profession ………………………………………………………………………… 1 - 5 The Advocate’s duty to assist the court ……………………………………………………... 5 - 7 R v C ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 - 15 Seeking to withdraw from a case ………………………………………………………………. 15 - 20 Assistance to the court …………………………………………………………………………….. 20 - 24 Nigel Teare’s lecture on The Advocate and the Deemster …………………………….. 24 - 26 Concise skeleton arguments ……………………………………………………………………… 26 - 33 Geoffrey Ma’s lecture on The Practice of Law : a Vocation Survives Amidst Globalisation ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 33 - 35 Unnecessary documentation …………………………………………………………….……….. 35 – 39 A useful Indian authority ………………………………………………………………………….. 39 - 40 Other authorities ……………………………………………………………………………………… 40 - 43 Request clarification of judgment where genuinely necessary .……………………… 43 Draw up draft order …………………..…………………………………………………………….. 43 - 45 Stand up to the Deemster ….……………………………………………………………………… 45 - 46 Disclosure duties ……………………………………………………………………………………... 46 - 53 The new litigation culture: expedition, proportionality and co-operation not confrontation ………………………………………..……………………..…………………………. 53 - 63 Recusal applications ……..…………………………………………………………………………. 63 Pressure ..………….……………………………………………………………………………………. 63 - 64 Lord Neuberger’s lecture on The Future of the Bar …………………………………….… 64 – 68 Rule of Law: special duty ………………………………………………………………………….. 68 - 71 Further reading ………………………………………………………………………………………… 71 - 72 DUTIES OF ADVOCATES TO THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE ISLE OF MAN The Advocate’s Oath 1. By his or her oath an advocate swears that the advocate “will truly and honestly demean myself in the practice and knowledge of an Advocate to the best of my ability.” This oath dates back to the Attorney’s Act 1777 and focuses on two crucial elements of the practice of an advocate. -

Remuneration for Scrutiny Roles

PP 2016/0111 STANDING COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON EMOLUMENTS FIRST REPORT 2015-16 REMUNERATION FOR SCRUTINY ROLES FIRST REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON EMOLUMENTS 2015-16: REMUNERATION FOR SCRUTINY ROLES The Committee shall - (i) consider and report to Tynwald on - (a) the emoluments of H E Lieutenant Governor, their Honours the First and Second Deemsters and the Judge of Appeal, H M Attorney General, the High Bailiff, the Deputy High Bailiff and the Clerk of Tynwald; (b) the Tynwald Membership Pension Scheme; and (c) in addition to its consultative functions set out in paragraph 4.3(ii) and as it thinks fit, the emoluments of Members of Tynwald; (ii) carry out its consultative functions under section 6(3) of the Payments of Members’ Expenses Act 1989, as the body designated by the Payment of Members’ Expenses (Designation of Consultative Body) Order 1989.” The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. Committee Membership The Hon S C Rodan SHK (Garff) (Chairman) Hon R H Quayle MHK (Middle) Mr D J Quirk MHK (Onchan) Mr C R Robertshaw MHK (Douglas East) Mr D M Anderson MLC Mr D C Cretney MLC Mr J R Turner MLC Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM1 3PW (Tel 01624 685520, Fax 01624 685522) or may be consulted at www.tynwald.org.im All correspondence with regard to this Report should be addressed to the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM1 3PW. -

Joint Committee on the Emoluments of Certain Public Servants First

PP66/08 J o in t C o m m it t ee on th e E m o lu m en t s of C er t a in P u blic Ser v a n t s F ir st R epo r t fo r th e Se ssio n 2007-2008 FIRST REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE EMOLUMENTS OF CERTAIN PUBLIC SERVANTS 2007/2008 Constituted 2nd and 30th March 1965 as a Standing Joint Committee to examine the amount of expenses paid to Members and the salaries of Senior Government Officials and Crown Officers. The Keys representatives are the members of the Consultative Committee of the House. By its First Report 1992/ 93 the terms of reference were revised as follows - (i) to consider and report to the Council and Keys on - (a) the emoluments of H E Lieutenant Governor, their Honours the First and Second Deemsters and the Judge of Appeal, H M Attorney General, the High Bailiff, the Deputy High Bailiff and the Clerk of Tynwald; (b) the Tynwald Membership Pension Scheme; and (c) in addition to its consultative functions set out in paragraph (i) and as it thinks fit, the emoluments of Members of Tynwald; (ii) to carry out its consultative functions under section 6(3) of the Payments of Members’ Expenses Act 1989, as the body designated by the Payment Of Members’ Expenses (Designation of Consultative Body) Order 1989. The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. -

Item Number Item Action Required 1. OPENING of the MEETING 1.1

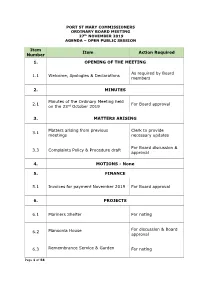

PORT ST MARY COMMISSIONERS ORDINARY BOARD MEETING 27th NOVEMBER 2019 AGENDA – OPEN PUBLIC SESSION Item Item Action Required Number 1. OPENING OF THE MEETING As required by Board 1.1 Welcome, Apologies & Declarations members 2. MINUTES Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting held 2.1 For Board approval on the 23rd October 2019 3. MATTERS ARISING Matters arising from previous Clerk to provide 3.1 meetings necessary updates For Board discussion & 3.3 Complaints Policy & Procedure draft approval 4. MOTIONS - None 5. FINANCE 5.1 Invoices for payment November 2019 For Board approval 6. PROJECTS 6.1 Mariners Shelter For noting For discussion & Board 6.2 Manxonia House approval 6.3 Remembrance Service & Garden For noting Page 1 of 58 6.4 Skate Park For noting 6.5 Public Conveniences For noting 6.6 Highways For noting 6.7 Happy Valley For noting 6.8 Boat Park For noting 6.9 Reduction in Board numbers For noting 6.10 Jetty Repair For noting 6.11 Bay Queen Exhibition For noting Mona’s Queen III Exhibition – Verbal 6.12 For noting update from the Chair For discussion & Board 6.13 Christmas approval 7. PUBLIC CORRESPONDENCE & COMMUNICATIONS 7.1 Letter of condolence For noting 7.2 Letter of thanks from Nick Watterson For noting 7.3 Tynwald Commissioner communication For noting Page 2 of 58 Communication from Manx Utilities re For Board discussion & 7.4 street light columns approval Communication from Waste 7.5 For noting Management Unit 7.6 3rd Supplemental Valuation List For noting Request from Rushen Silver Band re For Board discussion & 7.7 street collection approval Scoill Phurt le Moirrey Play Area – 7.8 Verbal item submitted by the Vice For Board discussion Chairman Correspondence from the Ministers 7.9 Watterson & Skelly regarding flood For discussion risks 7.10 Letter received from Mr Merchant For discussion 8. -

Appointment of Deemster Information Pack

APPOINTMENT OF DEEMSTER INFORMATION PACK Cabinet Office October 2019 1 Contents 1. Advertisement ............................................................................................... 3 2. Office Description .......................................................................................... 4 3. Person Specification ....................................................................................... 5 4. Selection Procedure ....................................................................................... 7 5. Main Terms and Conditions of Appointment as Deemster ................................. 8 2 1. Advertisement Appointment of Deemster The Isle of Man prides itself on its values of democracy, good government and the importance of the rule of law. The judiciary is a key component of delivering these values and to the Island’s international reputation. Applications are invited from on and off-Island candidates for the position of Deemster. This is a Crown appointment made by His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor pursuant to section 3B (1) of the High Court Act 1991. This is a full time role, however consideration will be given to job share partnerships (which would not necessarily require full-time residence on the Isle of Man) and if interested you should discuss this with the First Deemster. The Deemster will be particularly responsible for presiding over the Court of General Gaol Delivery (which is broadly equivalent to the Crown Court in England and Wales). The Deemster will also be responsible for administration, ceremonial and other duties assigned by the First Deemster. The Deemster will hold office at the pleasure of His Excellency. The appointment will be on the advice of a Selection Panel. Candidates for this position must meet the following criteria:- • A qualified advocate, barrister or solicitor of at least 10 years standing. • Relevant judicial experience either in the Isle of Man or elsewhere within the British Isles for a minimum of 3 years (full or part time) prior to taking up office. -

Report – Part 1 a M Thompson 2017 Skelly Shimmin Reduced

REPORT OF REVIEW OF THE ACTIONS OF MINISTERS SHIMMIN AND SKELLY AND WHETHER THEY KNOWINGLY FAILED TO DECLARE A CONFLICT IN RELATION TO PLANNING APPLICATION 15/00124/B PART 1 ANGELA MAIN THOMPSON O.B.E. DATED 18 FEBRUARY 2017 The Complainant APPENDIX 4: Correspondence with the Ministers ........................................................................................ 64 3 The development and lodged his paper on 20 May 2015, complainantwas included as an "interested person". 6. The appointed independent Planning Inspector, Mr Stephen Amos, held an inquiry on 17 June 2015, following a site visit on 15 June. Meary Voar Developments Ltd was represented by Mr G. Steele QC who called evidence from the architect and a town planning consultant. g,:,plainant who had provided written objections also gave evidence and the senior planning officer, Witnessc , was also questioned. 7. Before dealing with the Inspector's recommendations, it is necessary to go back to the original application made in 2011 and approved in 2012. That application was contentious and, as indicated, opposed by �,ptainant. Between the application being lodged and its consideration by the Planning Committee, the then Minister for Infrastructure, Mr David Cretney, presented to Tynwald in February 2012 a consultation document on a draft planning policy statement C'PPS") which was to have immediate effect. The purpose of the statement was to ensure that the planning system supported economic and employment growth. The Department would have regard to the development plan and, in particular, would seek proposals to be supported by evidence demonstrating that the proposed development would secure sustainable, long-term, economic growth of Island-wide benefit. -

Valedictory Ceremony on the Retirement of Judge of Appeal Geoffrey Tattersall Qc

VALEDICTORY CEREMONY ON THE RETIREMENT OF JUDGE OF APPEAL GEOFFREY TATTERSALL QC Held in Court 3 on 21 September 2017 Address by His Honour Deemster Doyle First Deemster and Clerk of the Rolls: Your Honours, Your Worships, Mr Attorney, Mr Clucas, ladies and gentlemen. This is an historic day of mixed emotions: principally sadness and joy. Sadness because we are saying goodbye to a true friend of the Island and joy because we can reflect upon Geoffrey’s impressive contribution to this Island and we can congratulate him on a job extremely well done. We can also look forward with confidence to the future under our new full-time resident Judge of Appeal who we will warmly welcome in due course and who will significantly bolster the rule of law in this jurisdiction; but back now to the present. This is the last High Court sitting in the Isle of Man of His Honour Judge of Appeal Geoffrey Frank Tattersall QC. I welcome you all, especially Geoffrey’s wife Hazel, and his daughters Victoria and Hannah, and Hannah’s husband Josh. This is also an historical moment for Hannah because I understand that she was present as a young 12 year old when Geoffrey was sworn in as the Judge of Appeal all those years ago now. Judges and lawyers like continuity, but fortunately they are not very good mathematicians so they have not yet worked out your age Hannah! Your secret is safe. Without the love and support of his family all of Geoffrey’s considerable achievements would not have been possible. -

CRIMINAL APPEALS (From the Court of General Gaol Delivery)

NOTES IN RESPECT OF TALKS TO TRAINEE MANX ADVOCATES [16 September 2019] CRIMINAL APPEALS (from the Court of General Gaol Delivery) C O N T E N T S Pages Jurisdiction..….…………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Re-hearing or review?.................................................................................... 1 Appeals against conviction....……………………………………………….……………………… 1 - 4 Appeals against sentence …………..…………………………………………………………….. 4 - 8 References on points of law..……………………………………………………………………… 8 References in respect of sentences stated by the Attorney General to be unduly lenient..………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 - 14 Appeals in respect of pre-trial rulings...……………………………………………………….. 14 - 17 Extensions of time……………………………………………………………………………………… 17 - 18 Bail pending appeal……………………………………………………………………………………. 19 Additional evidence………………………………………………………………………………………… 19 - 20 Dealing with appeals in absence of appellant……………………………………………….. 20 - 21 Costs……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 21 Leave to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ……………………. 21 – 26 Doleance and the Court of General Gaol Delivery………………………………………… 26 - 28 Further reading...……………………………………………………………………………………... 28 CRIMINAL APPEALS Jurisdiction 1. See Hafner 2007 MLR 180 (Appeal Division judgment 31 August 2007) for an outline of the statutory jurisdiction of the Appeal Division in criminal matters. The Appeal Division owes its jurisdiction to statute and it is crucial to consider the relevant statutory framework contained in the Criminal Jurisdiction -

Lawyers' Empires: the Anglicisation of the Manx Bar and Judiciary

LAWYERS' EMPIRES: THE ANGLICISATION OF THE MANX BAR AND JUDICIARY Peter W. Edge* I. INTRODUCTON The Isle of Man is a very small jurisdiction, roughly equidistant from England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. At various times in its histo- ry it has been dominated by one or other of its larger neighbours. Since 1765 it has been under the political and legal control of the British Crown, although the Isle of Man has never been absorbed into the United Kingdom. The special status of the Isle of Man as a separate territory, rather than an administrative unit such as a county, has led to it retaining its own unique laws and legal system.' Thus, there are distinct Manx courts, manned by distinctively Manx judicial officers, administering a body of law which, while often identical to English law in content, remained formally distinct and, in some areas, different in substance. This unique legal system was, after 1777, served by a local, profes- sional bar. The Manx Bar is a unified body, by which is meant that all the functions required of a legal profession are carried out by a single profession-the advocates-rather than dividing the roles between two separate professions-such as the barrister and solicitor in England. Thus, after 1777 a single professional body was responsible for providing legal advice to private individuals and state officials and arguing cases in the Manx courts. I have approached the Anglicisation of the Manx legal system from * Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Central Lancashire. Ph.D., Cambridge University, 1994; LL.B., Lancaster University, 1989. -

'WORTHY of NOTICE': the LEGAL SYSTEM and CUSTOMARY LAWS in the ISLE of MAN Jennifer Corrin*

43 'WORTHY OF NOTICE': THE LEGAL SYSTEM AND CUSTOMARY LAWS IN THE ISLE OF MAN Jennifer Corrin* Commencing with some background on Isle of Man and its history, this article gives an overview of the legal system of the Isle of Man, including the sources of law and courts. It then looks more specifically at the nature and role of customary law on the island. The article explores two examples of longstanding customary laws (legitimacy and inheritance, and treasure trove), which remained in force until relatively recently. It concludes that, whilst the Manx legal system is strongly influenced by the English common law system, it has retained its unique character, stemming from its legal heritage. L'île de Man est une dépendance de la Couronne britannique. Après un bref rappel historique de l'évolution de son statut, l'auteure propose aux lecteurs un aperçu des composantes de son système juridique actuel. Les développements portent ensuite sur la place et la portée du droit coutumier encore pregnant dans cette dépendance et plus spécifiquement sur les règles qui sont restées en vigueur jusqu'à une date relativement récente, concernant le droit de succession et la découverte, par le pur effet du hasard, d'une chose cachée ou enfouie. En guise de conclusion, l'auteure estime que si le système juridique de l'île de Man est fortement influencé par le système de la Common Law anglaise, il a néanmoins conservé un caractère unique, conséquence de son héritage juridique. I INTRODUCTION The Isle of Man is a small island marooned in the middle of the Irish sea. -

Final Report of the Select Committee on Complaints of Maladministration Made by Mrs a E S J Pilling

IvN 0012_ 102 FINAL REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON COMPLAINTS OF MALADMINISTRATION MADE BY MRS A E S J PILLING To: The Hon Noel Q Cringle, President of Tynwald, and the Hon Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled FINAL REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON COMPLAINTS OF MALADMINISTRATION MADE BY MRS AE S J PILLING I INTRODUCTION Terms of Reference of the Committee 1. At its October 2000 sitting, Tynwald Court resolved: "That, following the presentation of a petition for redress presented by Anne Elizabeth Saria Jill Pilling at Tynwald assembled at St John's on 5th July 2000, a Select Committee of three Members be appointed to consider:- (i) the circumstances surrounding the failure to make an audio recording of the High Court action between Mrs Pilling and the Department of Local Government and the Environment before Acting Deemster Michael Shorrock QC on 16th July 1998; and (ii) the application of the standardised procedure for complaints against Departments of the Isle of Man Government and Statutory Boards in respect of complaints allegedly made by Mrs Pilling between 1991 and 1993, and her complaint of the failure to record the 1998 court action; and to report." C /CMPil / mck Membership of the Committee 2.01 At the same sitting Mr L I Singer, Sir Miles Walker and Mr J N Radcliffe were appointed to serve on the Select Committee. At the sitting of the Court on 17th January 2002, Mrs H Hannan was elected to serve on your Committee in place of Sir Miles Walker who had retired at the General Election in November 2001.