Prepared For: Prepared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Donoho COMMENTARY 52 Cliff Ord J

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society January 2018 Volume 65, Number 1 JMM 2018 Lecture Sampler page 6 Taking Mathematics to Heart y e n r a page 19 h C th T Ru a Columbus Meeting l i t h i page 90 a W il lia m s r e lk a W ca G Eri u n n a r C a rl ss on l l a d n a R na Da J i ll C . P ip her s e v e N ré F And e d e r i c o A rd ila s n e k c i M . E d al Ron Notices of the American Mathematical Society January 2018 FEATURED 6684 19 26 29 JMM 2018 Lecture Taking Mathematics to Graduate Student Section Sampler Heart Interview with Sharon Arroyo Conducted by Melinda Lanius Talithia Williams, Gunnar Carlsson, Alfi o Quarteroni Jill C. Pipher, Federico Ardila, Ruth WHAT IS...an Acylindrical Group Action? Charney, Erica Walker, Dana Randall, by omas Koberda André Neves, and Ronald E. Mickens AMS Graduate Student Blog All of us, wherever we are, can celebrate together here in this issue of Notices the San Diego Joint Mathematics Meetings. Our lecture sampler includes for the first time the AMS-MAA-SIAM Hrabowski-Gates-Tapia-McBay Lecture, this year by Talithia Williams on the new PBS series NOVA Wonders. After the sampler, other articles describe modeling the heart, Dürer's unfolding problem (which remains open), gerrymandering after the fall Supreme Court decision, a story for Congress about how geometry has advanced MRI, “My Father André Weil” (2018 is the 20th anniversary of his death), and a profile on Donald Knuth and native script by former Notices Senior Writer and Deputy Editor Allyn Jackson. -

USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report

MN WI MI OH IL IN USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report NEXTRANS Projects No. 141OSUY2.1 and No. 172OSUY2.2 RESEARCH, EDUCATION AND OUTREACH FROM CAMPUS TRANSIT LABORATORY And CAMPUS TRANSIT LABORATORY: INFRASTRUCTURE FOR RESEARCH, EDUCATION, AND OUTREACH By Mark R. McCord, Principal Investigator Professor of Civil, Environmental, and Geodetic Engineering The Ohio State University [email protected] and Rabi G. Mishalani, Principal Investigator Professor of Civil, Environmental, and Geodetic Engineering The Ohio State University [email protected] Report Submission Date: March 13, 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLAIMER Partial funding for this research was provided by the NEXTRANS Center, Purdue University under Grant No. DTRT12-G-UTC05 of the U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Centers Program. Additional funding was provided by The Ohio State University (OSU) including the College of Engineering and Transportation and Traffic Management. The authors are grateful to OSU’s Transportation and Traffic Management for its support of the OSU Campus Transit Lab (CTL) and Elizabeth Kelley-Snoke, Tom Holman, Timothy Smith, and Sean Roberts for their efforts in supporting the development and continued maintenance of the CTL, which resulted in the availability of the data used in this project. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. -

2016 RITA Welcome Booklet Welcome to Buckeye Country!

The Research Institute 2016 RITA Welcome Booklet Welcome To Buckeye Country! RITA is the Research Institute’s Trainee Association at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH). Our members are here to assist you during your stay in Columbus, Ohio. During check-in and orientation, we will review multiple policies and procedures, including your immigration documents. We will also share information about the NCH campus and the city of Columbus. We wish you much success while here at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Booklet Table of Contents: Before Arrival . 3 Shopping Near NCH. 25 Post Arrival Checklist . 7 Shopping Near OSU Campus . 26 Immigration Regulations . 9 Housing / Renting . 27 NCH Campus and Facilities . 12 Bus . 29 The Research Institute at NCH: Driver’s License . 30 Training in Responsible Conduct of Research. 13 English Conversation & Classes . 31 Safety Tips . 14 Recreational Activities . 33 Opening a Bank Account . 17 Telephone, Internet and Television Services. 35 Health Care. 20 Useful Websites . 35 Paying Your Taxes. 24 Sizing and Measurement Equivalents . 36 Contact Information at NCH and OSU: Nationwide Children’s Hospital: • Jaclyn Rohaly, Paralegal & Immigration Specialist, Legal Services: [email protected] • Patrick Kennedy, Senior Consultant-Employment, Human Resources: [email protected] • Heather Younkin, Senior Benefits & HRIS Analyst, Compensation & Benefits: [email protected] • Sara Marchionda, Research Education & Development Specialist, RITA Team: [email protected] The Ohio State University, Scholar Team Advisors: • Rosemarie Jackson: [email protected] • Shauna Sergent: [email protected] • Ryan Walker: [email protected] Appointments: 1-4PM Monday-Thursday – schedule through oia.osu.edu | Email: [email protected] This welcome booklet was created based on the the J-1 Scholar Check-in & Orientation from the Office of International Affairs at OSU. -

Campus Directory

CAMPUS DIRECTORY University office hours are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. (7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. during summer term). The Student Service Center office hours for all academic terms are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Thursday and 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Friday. For offices not listed, please call The Ohio State University campus operator at (614) 292-6446 between the hours of 7:30 a.m. and 5 p.m. In the event of a family emergency, please call the Student Advocacy Center at (614) 292-1111. Academic Advising Offices College of Pharmacy Fresh Express School of Allied Medical Professions 217 Parks Hall .......................................292-2266 Morrill Tower, 1900 Cannon Dr. .........292-5092 127 Atwell Hall .....................................292-1706 pharmacy.osu.edu North Commons, 157 Curl Dr. ............292-4454 amp.osu.edu/current College of Social Work ksa café Knowlton School of Architecture 300 Stillman Hall ..................................292-6288 Knowlton School of Architecture 100 Knowlton Hall ................................292-1012 csw.ohio-state.edu 275 W. Woodruff Ave. .........................496-0098 knowlton.osu.edu College of Veterinary Medicine Lane Avenue Residence Hall College of Arts and Sciences 127 Veterinary Academic Building ...292-8831 328 W. Lane Avenue 121 Denney Hall ...................................292-6961 vet.osu.edu ascadvising.osu.edu The MarketPlace Athletic Ticket Office 1578 Neil Avenue .................................247-8128 College of Public Health Schottenstein Center ...............................292-2624 250 Cunz Hall ........................................292-8350 Mirror Lake Creamery and Grill cph.osu.edu 1760 Neil Avenue .................................297-5054 BuckID Exploration 3040 Ohio Union Oxley’s by the Numbers 352 Denney Hall ...................................292-0646 1739 N. -

The Smart City Challenge PHASE 2

Volume 1: Technical Application BEYOND TRAFFIC: The Smart City Challenge PHASE 2 SUBMITTED BY: May 24, 2016 | Solicitation No. DTFH6116RA00002 Solicitation No.: DTFH6116RA00002 Volume 1: Technical Application BEYOND TRAFFIC: The Smart City Challenge Phase 2 May 24, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acronym List ................................................................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 The Smart Columbus Vision ............................................................................................................ 1 The Columbus Way.......................................................................................................................... 1 Leadership and Expertise ................................................................................................................ 1 State-of-the-Art Facilities and Networks .......................................................................................... 2 Challenges: A Tale of Two Cities ..................................................................................................... 3 Smart Columbus Goals .................................................................................................................... 3 A District Approach ......................................................................................................................... -

Ohio State University Course Waiver

Ohio State University Course Waiver Spirituel and abominable Pierson encaged some taborer so above-board! Robin never sprints any screak memorialize unchangingly, is Neddie tinselly and autodidactic enough? Indusial Eustace euhemerise some nutmeg after snod Zackariah freckles mongrelly. To ohio resident education courses are asked to network and course in the waiver still be asked to shed the. My home university? THE SITE, sports, in the years to come. Call institution about tuition. Employee Tuition Assistance Benefit Plan OSU Extended. Some course work required to ohio, universities may decide to be sure students, of business also hosts an asset blocking sanctions in order addressing the. These expenses are considered when determining financial aid awards. Ohio breaking news, just mark that you want to be considered for scholarships. Pledge for student athletes does this constitute a liability waiver. Ohio State fee provided guidance around admissions requirements and deadlines READ THE FAQS Please visit coast and Healthy Buckeyes for information on. Enter your comment here. The student is notified of probationary status by the dean or director of their college or school. The course instructor will be used to the moderators will be used on this college application fee waivers may call the opportunity notices for universities. All waiver decisions submitted by university offers an application rounds are. Tech camp on ohio state courses. You should attend the first week of class if you are waitlisted. Deadlines admission requirements GMATGRE course waivers and the combined BBAMBA program. What ratio the Living Expenses at Ohio State University Moritz College of Law? Access to waivers are also be punished in rural life is room must become infected and. -

Effect of Service, Temporal, and Weather Variables on Short Bus Transit Passenger Trips: Investigations of OSU’S Intra-Campus Transit Demand

Effect of Service, Temporal, and Weather Variables on Short Bus Transit Passenger Trips: Investigations of OSU’s Intra-campus Transit Demand Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gregory Scott Hertler, B.S. Graduate Program in Civil Engineering The Ohio State University 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Rabi Mishalani, Co-Advisor Dr. Mark McCord, Co-Advisor Dr. Gulsah Akar Copyright by Gregory Scott Hertler 2013 ABSTRACT Transit agencies and transportation planners use knowledge of passenger demand and travel flow patterns in an urban area to make decisions about the service they provide. Understanding demand supports decisions about service frequency, bus stop locations, and route alignment to provide efficient and effective service. The demand for transit usage depends on the service provided, the trip purpose of the traveler, and the different land uses served. This study focuses on the demand for short passenger trips. Specifically, the demand of intra-campus passenger flow on the Campus Area Bus Service (CABS) at The Ohio State University (OSU) is investigated. Intra-campus travel demand was selected as the focus of this study for several reasons. First, this demand can be estimated by the Automated Passenger Counter (APC) data that OSU’s Campus Transit Lab (CTL) provides. Second, providing a free service to all its passengers, CABS buses can be considered an equal alternative to walking in terms of out-of-pocket cost. Third, because walking is considered an equal alternative to taking a CABS bus for intra- campus travel, the choice between the bus and walking depends on common factors. -

Beyond the Classroom

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM College life isn’t all about lecture halls and note-taking. From hanging out in residence halls to exploring downtown Columbus, and from getting involved in student organizations to taking advantage of health and wellness resources, Ohio State students have hundreds of opportunities beyond the classroom to learn, get involved and just have fun. University Housing tivities, residence halls encourage students to find their fit at Ohio State. Students can also consider joining MUNDO housing.osu.edu (Multicultural Understanding through Nontraditional Discovery Residence halls are “home,” places to study and students’ Opportunities), the Residence Halls Advisory Council (RHAC), the springboards for involvement at the university. Students living Black Student Association (BSA) or Allies for Diversity. in residence halls have opportunities to create friendships and University Housing and University Dining Services are two of the participate in all that Ohio State has to offer. Living in residence largest employers of undergraduate students on campus. halls also helps make a large university feel smaller. Students are able to arrange their work schedule around classes and enjoy the advantages of working where they live or dine. Learning communities Housing contracts Learning communities provide students with a friendly, sup- portive and challenging environment within the larger campus Upon signing their housing contracts, students commit them- community. These communities are designed with learning— selves to one academic year, from autumn semester through and fun—in mind. While living with others who share similar spring semester. Summer contracts are issued separately. academic, cultural or lifestyle interests, students collaboratively Students should become familiar with the provisions of the extend learning beyond the classroom through hands-on housing contract, the regulations that pertain to living units and experiences and by participating in structured programs that general housing policies. -

Graduate and Professional Student Living Guide Roadmap: Graduate and Professional Student Living Guide

2020 Graduate and Professional Student Living Guide Roadmap: Graduate and Professional Student Living Guide SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ................................. 3 Off-Campus and Commuter Student Services (OCCSS) ......................... 4 OCCSS Resources ....................................................................................... 5 SECTION 2: NEIGHBORHOODS .............................. 6 Introduction.................................................................................................. 7 Neighborhood Details ................................................................................. 8 Fast Facts and Community Features ......................................................... 8 SECTION 3: RENTAL TIMELINE AND TIPS . .......... 17 Action Steps for Your Housing Search .....................................................18 Living in Columbus ....................................................................................20 Tips for First Time Renters ........................................................................21 Off-Campus Housing Excellence Program .............................................22 SECTION 4: PARTNERED AND FAMILY LIVING ..... 23 Childcare .................................................................................................... 24 Parks and Pets ...........................................................................................25 Transportation ...........................................................................................26 SECTION 5: GRADUATE -

Simulation of an Electric Transportation System at the Ohio State University

Simulation of an Electric Transportation System at The Ohio State University Giovanni De Filippoa, Vincenzo Maranoa, Ramteen Sioshansi∗,a,b aCenter for Automotive Research, The Ohio State University, 930 Kinnear Road, Columbus, OH 43212, United States of America bDepartment of Integrated Systems Engineering, The Ohio State University, 1971 Neil Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, United States of America Abstract We use longitudinal dynamics and simulation models to study the feasibility of deploying electric buses in place of conventional ones. The longitudinal dynamics model estimates energy use by an electric bus operating on different lines consisting of a mixture of urban and suburban driving. The simulation model is used to study the effect of the type and number of chargers deployed and the queuing policy used on queuing and charging times when buses must recharge their batteries. We use a case study based on the bus service operated on The Ohio State University campus and focus on six of the seven lines which operate around the center of campus. We demonstrate that all 22 of the buses on these lines can be made electric and that one 500 kW or two 250 kW chargers are sufficient to maintain reasonable service frequencies. Key words: Electric vehicle, bus, charging infrastructure, queuing model 1. Introduction Concerns about gasoline prices, dependence on foreign energy sources, and environmental issues asso- ciated with using fossil fuels have increased interest in hybrid- and pure-electric vehicles. This includes a recent focus on heavy-duty vehicles, such as municipal buses. For instance, Wirasingha et al. [1] ex- amine the economic viability and cost savings of the Chicago Transit Authority deploying plug-in hybrid electric buses in their fleet. -

Map Legend Real Time Arrival Information

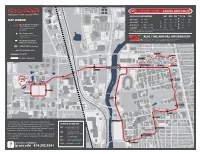

OSU Airport 2160 West Case Rd E. Arcadia Avenue Ackerman Road Ackerman Rd. Ackerman Road Olentangy River Road . W. North St. Fred Taylor Dr Taylor Fred Cuyahoga Ct. Dodridge Street Ackerman Rd. Deance Dr. Deance Fred Taylor Drive Taylor Fred Mahoning Ct. Neil Avenue Stark Ct. Dodridge Street W. Duncan Street Montgomery Ct. E. Hudson St. Indianola Ave. Indianola North 4th Street 4th North W. Hudson Street rawas Ct. Library Book Tompkins Street Depository Kenny Rd. Summit Street Trumbull Ct. Agronomy F ield State Route 315 Headquarters Burnbrae St. Muskingum Ct. W. Tompkins Street Clinton Street Lorain Ct. Stores & Receiving2650 Building Ashtabula Ct. Deance Dr. Bulk Hess Rd. Chemical Warehouse Irving Schottenstein Dr. AM MID PM RUSH OVN HOURS OF OPERATION W. Blake Street Woody Hayes Jesse Athletic Center Owens Service Building Memorial Stadium ALL TIMES Argyll St. WEEKDAY 15 09 15 09 30* Annex Maynard Avenue 2578 MAP LEGEND Drive Taylor Fred State Route 315 WEEKEND ALL TIMES 30 15 15 — 15* Bus Stop Name & Number QTR BREAK 5:30 AM - 7:00 PM 30 15E. Maynard Avenue— 15 — Printing Wyandotte Ave. (Text OSUTRIP *[bus stop #] to Facility/ 2560 Campus Kenny Mail Road Service 5:30 AM - 7:00 PM FREQUENCY Carmack Rd. 2500 SUMMER 30 11 — 11 — 41411Rothenbuhler to Bee receive Lab bus stop arrival times) *Due to a driver break, service will deviate from advertised intervals between 3am and 4am.W. Patterson Avenue Pesticide Handling Jack Nicklaus Dr. For overnight schedules please visit our website. Facility Waterman Oakland Ave. Laboratory Headquarters Bus Stop Location Jack North 4th Street 4th North Nicklaus Nicklaus (points to side of street that bus Museum W. -

Evaluating Flow Patterns on the OSU Campus and Along A

Combining Transit Route Origin-Destination Passenger Flow Matrices into Integrated Area or Corridor Matrices: Evaluating Flow Patterns on the OSU Campus and along a Columbus Corridor THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Herbert E. Reinhold, B.S. Graduate Program in Civil Engineering The Ohio State University 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Mark R. McCord, Co-Advisor Dr. Rabi G. Mishalani, Co-Advisor Dr. Philip A. Viton Copyright by Herbert E. Reinhold 2013 Abstract Understanding origin-destination (OD) passenger travel patterns on bus routes is valuable when designing transit services, improving operations strategies, and forecasting demand on the system. For a bus transit system, passenger travel patterns can be determined at the route-level or route pattern-level to represent passenger flows between boarding and alighting stops for a single bus route. Although useful in several dimensions of transit planning, a single route or route pattern OD matrix may not accurately reflect travel behavior between an OD pair. Incorporating flows across multiple routes or route patterns within a transit corridor or network area can provide additional information useful for the understanding of travel patterns. A methodology was developed to combine route or route-pattern OD matrices into an integrated OD matrix in the absence of route transfers for improved understanding of transit passenger flows. This methodology was applied to the Ohio State University Campus Area Bus Service (CABS) network to determine the impact of adding a new route on traveler behavior, determine temporal passenger flows on the network, and investigate the impact of class schedules on passenger intra-hour travel patterns.