No Golden Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving Emergency Care in Uganda a Low-Cost Emergency Care Initiative Has Halved Deaths Due to Emergency Conditions in Two District Hospitals in Uganda

News Improving emergency care in Uganda A low-cost emergency care initiative has halved deaths due to emergency conditions in two district hospitals in Uganda. The intervention is being scaled up nationally. Gary Humphreys reports. Halimah Adam, a nurse at the Mubende countries have no emergency access In Uganda, road traffic crashes are regional referral hospital in Uganda, telephone number to call for an ambu- a matter of particular concern. “Uganda remembers the little boy well. “He was lance, and many countries have no am- has one of the highest incidences of brought into the hospital by his mother,” bulances to call. Hospitals lack dedicated road traffic trauma and deaths on the she says. “He was unconscious and emergency units and have few providers African continent,” says Joseph Ka- barely breathing.” trained in the recognition and manage- lanzi, Senior House Officer, Emergency The mother told Halimah that the ment of emergency conditions. Medicine, Makerere University College boy had drunk paraffin, mistaking it “Over half of deaths in low- and of Health Sciences. “We are faced with for a soft drink. Paraffin (kerosene) is middle-income countries are caused multiple road traffic crashes daily and poorly absorbed by the gastrointestinal by conditions that could be addressed have barely any dedicated emergency tract, but when aspirated, which can by effective emergency care,” says Dr re s p on s e .” happen when a child vomits, it causes Teri Reynolds, an expert in emergency, According to WHO’s Global status lung inflammation, preventing the lungs trauma and acute care at the World report on road safety 2018, road traffic from oxygenating the blood. -

Museveni Receives Go Forward Executive

4 NEW VISION, Tuesday, February 2, 2016 ELECTION 2016 68 Mbabazi security men defect to NRM By Eddie Ssejjoba were formerly working as private security guards Sixty-eight musclemen and in Iraq, Afghanistan and women, claiming to belong Somalia, while others are to independent presidential veteran soldiers. candidate Amama Mbabazi’s The Team Thorough private security detail have spokesman, Godfrey Kimera defected to the National Babi, said the group would be Resistance Movement (NRM) stationed in Kampala to boost camp. the party’s security during the Composed of nine women, days left to the polling day. the group, which claimed He said for some time, they to have participated in the had been persuading the clashes with NRM supporters men, contacting them one in Ntungamo district on by one, to leave the Mbabazi December 12 last year, team and they had studied yesterday evening showed their behaviour since they up at the Team Thorough renounced their membership NRM party offices on Luthuli of Go Forward. Avenue in Kampala, wearing Ssebyala, however, said they T-shirts with the inscriptions have not heard from their of Go Forward, Mbabazi’s leader, Christopher Aine, Leaders of Go Forward from Sebei region in eastern Uganda, who defected to NRM, being introduced to political pressure group. since the Ntungamo clashes. supporters of candidate Yoweri Museveni during a rally in Kassanda, Mubende district on Sunday. PPU photo Team Thorough is a group Ntungamo was the scene of mostly youthful NRM of ugly clashes between mobilisers. supporters of the NRM and One of the bodyguards’ Go Forward on December leaders, Peter Okello, read a 12, after which Aine’s name statement before journalists, featured prominently as one stating that they had come out of the perpetrators of the Museveni receives boldly to inform the public violence. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Uganda Workplace HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (WAPP)

Uganda Workplace HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (WAPP) Kyenjojo Mubende Kampala RTI International is implementing a 4-year (2003–2007) HIV prevention and impact mitigation project that seeks Masaka to stem HIV infections in Ugandan informal-sector workplaces. Funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, the program provides support for approaches that include ■ “ABC” (abstinence, being faithful, condom use) HIV prevention methods Accomplishments to date ■ Prevention of mother-to-child transmission During the past 2 years, RTI has reached nearly 530,000 ■ Reduction of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and people through project-supported programs. Informal- discrimination at the workplace sector workers reached include market vendors, boda ■ Mitigation of the impact of HIV/AIDS among informal- boda (motorcycle and bicycle) transporters, carpenters, sector workers and their families. fi shermen and fi sh processors, taxi operators, food vendors and attendants, bar and lodge attendants, shop attendants, Collaboration shoe shiners, and tea harvesters. Project-supported activities We collaborate closely with the government, national and include the following: international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and community- and faith-based organizations (CBOs and Group education on HIV/AIDS FBOs). Th e program strengthens the ability of CBOs and With its partner FBOs and CBOs, RTI has successfully FBOs to better implement HIV/AIDS activities locally. organized 850 HIV/AIDS education and awareness campaigns for informal-sector workers that include Operating in Kampala, Kyenjojo, Masaka, and Mubende/ health talks, drama, and testimonies from persons living Mityana districts, RTI’s approach is to reach a large number with HIV/AIDS, combined with dialogue sessions where of informal-sector workers with HIV prevention and participants are encouraged to ask questions and off er mitigation messages through cost-eff ective and effi cient their own perspectives on HIV prevention. -

Planned Shutdown Web October 2020.Indd

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR SEPTEMBER 2020 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED Kampala West Saturday 3rd October 2020 Mutundwe Kampala South 1 33kV Replacement of rotten vertical section at SAFARI gardens Najja Najja Non and completion of flying angle at MUKUTANO mutundwe. North Eastern Saturday 3rd October 2020 Tororo Main Mbale 1 33kV Create Two Tee-offs at Namicero Village MBALE Bubulo T/C, Bududa Tc Bulukyeke, Naisu, Bukigayi, Kufu, Bugobero, Bupoto Namisindwa, Magale, Namutembi Kampala West Sunday 4th October 2020 Kampala North 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX2 Routine Maintenance of 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX 2 Wandegeya Hilton Hotel, Nsooda Atc Mast, Kawempe Hariss International, Kawempe Town, Spencon,Kyadondo, Tula Rd, Ngondwe Feeds, Jinja Kawempe, Maganjo, Kagoma, Kidokolo, Kawempe Mbogo, Kalerwe, Elisa Zone, Kanyanya, Bahai, Kitala Taso, Kilokole, Namere, Lusanjja, Kitezi, Katalemwa Estates, Komamboga, Mambule Rd, Bwaise Tc, Kazo, Nabweru Rd, Lugoba Kazinga, Mawanda Rd, East Nsooba, Kyebando, Tilupati Industrial Park, Mulago Hill, Turfnel Drive, Tagole Cresent, Kamwokya, Kubiri Gayaza Rd, Katanga, Wandegeya Byashara Street, Wandegaya Tc, Bombo Rd, Makerere University, Veterans Mkt, Mulago Hospital, Makerere Kavule, Makerere Kikumikikumi, Makerere Kikoni, Mulago, Nalweuba Zone Kampala East Sunday 4th October 2020 Jinja Industrial Walukuba 11kV Feeder Jinja Industrial 11kV feeders upgrade JINJA Walukuba Village Area, Masese, National Water Kampala East -

SSH4A Uganda Poster 1

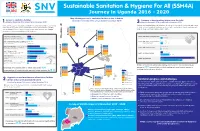

Sustainable Sanitation & Hygiene For All (SSH4A) Journey in Uganda 2016 - 2020 Map showing access to sanitation facilities in the 9 districts Access to sanitation facilities (Baseline December 2016 versus Endline November 2019) Presence of hand washing station near the toilet 1. (Baseline December 2016 versus Endline November 2019) 3.(Baseline December 2016 versus Endline November 2019) Universal access to adequate sanitation is a fundamental need, human N Having and maintaining a toilet alone is not good enough. Households also need BL 1.6% right and a key part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). EL 0.0% to have a hand washing facility near their toilet and practice hand washing with The 9 SSH4A Districts were supported by SNV through the SSH4A BL 35.9% soap to improve their hygiene and health. EL 49.2% BL 11.6% program to improve sanitation and Hygiene. BL 32.8% EL 1.3% EL 32.2% BL 36.0% BL 21.1% ZOMBO EL 34.6% EL 12.7% BL 17.4% 2016 0.15% Level 5: Environmentally safe toilets 2016 7.5% EL 10.3% Level 4: HW station running tap water (a toilet where the faecal sludge does not 2019 6.8% 2019 9.8% BL 22.1% contaminate/leak into the environment) EL 43.6% PAKWACH Level 4: Improved toilets with fly management 2016 1.2% Level 3: HW station, no contamination 2016 0.42% (an improved latrine that does not allow flies to (has running water) get out of the latrine) 2019 0.3% 2019 7.04% BL 37.6% EL 3.8% BL 54.6% Level 3: Improved toilets (a toilet that has a slab BL 34.2% 2016 23.9% BL 6.6% EL 1.7% 2016 0.32 % with one hole, a door/screen -

Newsletter Issue 18| January - June| 2018 / Mildmay Uganda Publication

Newsletter Issue 18| January - June| 2018 / Mildmay Uganda Publication BISHOP OF MITYANA DIOCESE VISITS MILDMAY UGANDA His Lordship Rt. Rev Stephen Kazimba, Bishop of Mityana Dioceses visits the Mildmay Uganda Laboratory. His Lordship Rt. Rev Stephen Kazimba, n March 22nd, 2018, His partnered with Mityana District to strength- Bishop of Mityana Diocese takes a group Lordship the Rt. Rev Stephen en health care service delivery through the photograph with the Mildmay Uganda Team Kazimba, Bishop of Mitya- Health Systems Strengthening project. during his visit. Ona diocese visited Mildmay Uganda. His Lordship was guided on a His Lordship blesses the Mildmay Uganda 30 Years tour around Mildmay Uganda hospital. Masterplan. Speaking to the Bethany Clinic team, Rt. Rev Stephen Kazimba said that dif- ferent people understand love differ- ently and pointed out that patients only understand the language of love. Speaking to the Bethany Clinic Team, Rt. Rev Stephen Kazimba explained “Patients only understand the lan- that different people understand love guage of love and you have that love of differently and pointed out that pa- God. My diocese is blessed to partner tients only understand the language Mildmay,” revealed Rt. Rev Stephen of love. Kazimba. Since 2005, Mildmay Uganda has PB Mildmay Uganda Newsletter Mildmay Uganda Newsletter 1 26th UNASNM Annual General Meeting Edith Akankwasa, Director MIHS opening the UNASNM Annual General Meeting rom 15th-18th March 2018, Mildmay Uganda “As you practice your nursing and midwifery profession Hundreds Benefit from School of Nursing and Midwifery hosted the have a sense of sacrifice and contribute positively to the 26th Uganda National Association of Students nation as stipulated in your anthem. -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

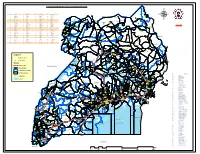

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Uganda National Roads Network

UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS NETWORK REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Musingo #" !P Kidepo a w K ± r i P !P e t Apoka gu a K m #" lo - g - L a o u k - #" g u P i #" n d Moyo!P g o i #"#" - t #"#" N i k #" KOBOKO M e g a #" #" #" l Nimule o #"!P a YUMBE #" u!P m ng m o #" e #" Laropi i #" ro ar KAABONG #" !P N m K #" (! - o - te o e om Kaabong#"!P g MOYO T c n o #" o #" L be Padibe !P - b K m !P LAMWO #" a oboko - Yu Yumbe #" om r K #" #" #" O #" Koboko #" #" - !P !P o Naam REGIONS AND STATIONS Moy n #" Lodonga Adjumani#" Atiak - #" Okora a #" Obongi #" !P #" #" a Loyoro #" p #" Ob #" KITGUM !P !P #" #" ong !P #" #" m A i o #" - #" - K #" Or u - o lik #" m L Omugo ul #" !P u d #" in itg o i g Kitgum t Maracha !P !P#" a K k #" !P #" #"#" a o !P p #" #" #" Atiak K #" e #" (!(! #" Kitgum Matidi l MARACHA P e - a #" A #"#" e #" #" ke d #" le G d #" #" i A l u a - Kitgum - P l n #" #" !P u ADJUMANI #" g n a Moyo e !P ei Terego b - r #" ot Kotido vu #" b A e Acholibur - K o Arua e g tr t u #" i r W #" o - O a a #" o n L m fe di - k Atanga KOTIDO eli #" ilia #" Rh #" l p N o r t h #"#" B ino Rhino !P o Ka Gulu !P ca #" #"#" aim ARUA mp - P #" #" !P Kotido Arua #" Camp Pajule go #" !P GULU on #" !P al im #" !PNariwo #" u #" - K b A ul r A r G de - i Lira a - Pa o a Bondo #" Amuru Jun w id m Moroto Aru #" ctio AMURU s ot !P #" n - A o #" !P A K i !P #" #" PADER N o r t h E a s t #" Inde w Kilak #" - #" e #" e AGAGO K #"#" !P a #" #" #" y #" a N o #" #" !P #" l w a Soroti e #"#" N Abim b - Gulu #" - K d ilak o b u !P #" Masindi !P i um !P Adilang n - n a O e #" -

FY 2019/20 Vote:625 Kasanda District

LG Approved Workplan Vote:625 Kasanda District FY 2019/20 Foreword The Local Government Act, CAP 243(as amended) devolves planning Powers to Local Councils in their areas of Jurisdiction. The Local Government Planning Cycle (second Budget call circular 2019) By the end of the Financial Year 2019/2020 the district expects to receive and spend19,614,574,000/= out of 18,4484,127,000was allocated to district head Quarters and 1,130,447,000/= was allocated to Lower Local Government Also requires every Higher Local Government to prepare Final Annual Workplans for Financial Year 2019/2020.Kassanda District is located in the Central Region of Uganda bordering Gomba, Kiboga, Mityana and Mubende Districts. It is comprised of three Town Council (Kassanda TC, Bukuya TC and Kiganda TC), two Counties (Kassanda County and Bukuya County) plus 3 constituencies ( kassanda south, Kassanda North and Bukuya) . Kassanda District had a population of 275,266 persons (Male=140,095 and Female= 135,171) according to National Population Housing Census 2014. The Current Population is Projected at 323,804 (Male=164,798 and Female= 159,006). Some of the areas in the district are hard to reach and others hard to stay. They include areas in Makokoto (Bbira). The District needs Transport to be able to fully implement council programmes. Many areas do not have access to hydroelectricity (Main Grid) and the road networks are poor. There¶s therefore need for the central Government to highly consider Kassanda District under various Government Programmes like Rural Electrification and road unit equipment. Uganda Road Fund is funding mainly road maintenance at the District level and community access roads at Sub County level. -

Emergency Health Fiscal and Growth Stabilization and Development

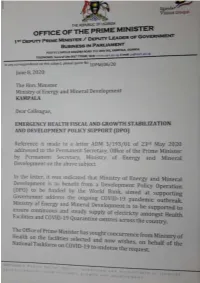

LIST OF COVID-19 QUARANTINE CENTRES IN WATER AND POWER UTILITIES OPERATION AREAS WATER S/N QUARANTINE CENTRE LOCATION POWER UTILITY UTILITY 1 MASAFU GENERAL HOSPITAL BUSIA UWS-E UMEME LTD 2 BUSWALE SECONDARY SCHOOL NAMAYINGO UWS-E UMEME LTD 3 KATAKWI ISOLATION CENTRE KATAKWI UWS-E UMEME LTD 4 BUKWO HC IV BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 5 AMANANG SECONDARY SCHOOL BUKWO UWS-E UMEME LTD 6 BUKIGAI HC III BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 7 BULUCHEKE SECONDARY SCHOOL BUDUDA UWS-E UMEME LTD 8 KATIKIT P/S-AMUDAT DISTRICT KATIKIT UWS-K UEDCL 9 NAMALU P/S- NAKAPIRIPIRIT DISTRICT NAMALU UWS-K UEDCL 10 ARENGESIEP S.S-NABILATUK DISTRICT ARENGESIEP UWS-K UEDCL 11 ABIM S.S- ABIM DISTRICT ABIM UWS-K UEDCL 12 KARENGA GIRLS P/S-KARENGA DISTRICT KARENGA UWS-K UMEME LTD 13 NAKAPELIMORU P/S- KOTIDO DISTRICT NAKAPELIMORU UWS-K UEDCL KOBULIN VOCATIONAL TRAINING CENTER- 14 NAPAK UWS-K UEDCL NAPAK DISTRICT 15 NADUNGET HCIII -MOROTO DISTRICT NADUNGET UWS-K UEDCL 16 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR UWS-N UEDCL 17 OYAM OYAM UWS-N UMEME LTD 18 PADIBE IN LAMWO DISTRICT LAMWO UWS-N UMEME LTD 19 OPIT IN OMORO OMORO UWS-N UMEME LTD 20 PABBO SS IN AMURU AMURU UWS-N UEDCL 21 DOUGLAS VILLA HOSTELS MAKERERE NWSC UMEME LTD 22 OLIMPIA HOSTEL KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD 23 LUTAYA GEOFREY NAJJANANKUMBI NWSC UMEME LTD 24 SEKYETE SHEM KIKONI NWSC UMEME LTD PLOT 27 BLKS A-F AKII 25 THE EMIN PASHA HOTEL NWSC UMEME LTD BUA RD 26 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD 27 ARCH APARTMENTS LTD KIGOWA NTINDA NWSC UMEME LTD 28 MARIUM S SANTA KYEYUNE KIWATULE NWSC UMEME LTD JINJA SCHOOL OF NURSING AND CLIVE ROAD JINJA 29 MIDWIFERY A/C UNDER MIN.OF P.O.BOX 43, JINJA, NWSC UMEME LTD EDUCATION& SPORTS UGANDA BUGONGA ROAD FTI 30 MAAIF(FISHERIES TRAINING INSTITUTE) NWSC UMEME LTD SCHOOL PLOT 4 GOWERS 31 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 2 GOWERS 32 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD ROAD PLOT 45/47 CHURCH 33 CENTRAL INN LIMITED NWSC UMEME LTD RD CENTRAL I INSTITUTE OF SURVEY & LAND PLOT B 2-5 STEVEN 34 NWSC 0 MANAGEMENT KABUYE CLOSE 35 SURVEY TRAINING SCHOOL GOWERS PARK NWSC 0 DIVISION B - 36 DR. -

Blood Screening for September 2010

September 08, 2010. TO NELEISH PATEL Founder/President - Healthcare Volunteer Inc. Dear President, RE: REPORT ON HIV/AIDS COUNSELING AND TESTING IN KIKANDWA KALWANA SUB-COUNTY HELD ON 09-08-2010: (L-R)The arrival and introduction of HVU staff and Local health volunteers in Kikandwa – Kalwana, Mubende district. (L-R)HVU Volunteers screening blood. Next picture, residents listening attentively from HVU briefing. This report is a summary of HIV testing result for the one testing event at Kikandwa trading center Kalwana sub-county Mubende district, Uganda and which held on 09th/08/2010.Testing was free for all. This Blood screening outreach event was organized and funded by Healthcare Volunteer Uganda (HVU) – under its Direct –Patient Care Program which is a sub set of the Multi –HIV/AIDS Preventive packages core program. This exercise was the second of its kind and this time around the organization used local Health Volunteers and nurses from partner health center and hospitals. So far two sub counties have had a chance, although not all the parishes/wards have been covered as of yet. Our target is to cover 5 sub counties; we have already carried out the exercise in 2 sub counties. The remaining 3 sub counties persie can as well be covered within a period of 120 days and each attracting average daily total of 154 clients. In order to realize this dream, this calls for support from well wishers and donors to help us with a support of $7800 for the whole exercise of blood screening for 120 days (for November, December, 2010 and January 2011 to be accomplished successfully.