Reconstructing Boundaries: Gender, War and Empire in British Cinema, 1945-1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

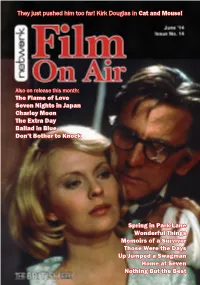

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

Look at Life on Talking Pictures TV Talking Pictures TV Are Delighted to Bring to the ‘Small Screen’ the ‘Big Screen’ Production: “Look at Life”

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 3rd May 2021 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Look at Life on Talking Pictures TV Talking Pictures TV are delighted to bring to the ‘small screen’ the ‘big screen’ production: “Look at Life”. All shot on 35mm, this iconic Rank production, made from the late 50s through to the early 60s, was a mainstay at all rank cinemas. Enjoy the cars, fashions, transport, and much more when you “Look at Life” again on Talking Pictures TV. The films will be airing throughout May. Monday 3rd May 12:10pm Tuesday 4th May 6:30pm Bank Holiday (1938) The Net (1953) Drama. Director: Carol Reed. Thriller. Director: Anthony Asquith. Stars: John Lodge, Margaret Lockwood, Stars: James Donald, Phyllis Calvert, Hugh Williams, Rene Ray, Wally Patch, Robert Beatty, Herbert Lom. A scientist Kathleen Harrison, Wilfrid Lawson and in a supersonic flight project risks his life. Felix Aylmer. A group of people encounter strange situations when they Wednesday 5th May 8:45am visit a resort to spend the weekend. The Sky-Bike (1967) Director: Charles Frend. Stars: Monday 3rd May 3pm Liam Redmond, William Lucas, Ian Ellis, Pollyanna (2002) Ellen McIntosh, Spencer Shires, Drama. Director: Sarah Harding. Della Rands, John Howard, Bill Shine, Stars: Amanda Burton, Georgina Terry David Lodge and Guy Standeven. and Kenneth Cranham. Adaptation of Young Tom builds a flying machine. the classic tale. Young orphan Pollyanna goes to stay with Aunt Polly, bringing Wednesday 5th May 12:20pm mirth and mayhem to her new home. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Spring 2011 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 65 Spring 2011 Issn 1476-6760 Christine Hallett on Historical Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Nursing Karen Nolte on the Relationship between Doctors and Nurses in Agnes Karll’s Letters Dian L. Baker, May Ying Ly, and Colleen Marie Pauza on Hmong Nurses in Laos during America’s Secret War, 1954- 1974 Elisabetta Babini on the Cinematic Representation of British Nurses in Biopics Anja Peters on Nanna Conti – the Nazis’ Reichshebammenführerin Lesley A. Hall on finding female healthcare workers in the archives Plus Four book reviews Committee news www.womenshistorynetwork.org 9 – 11 September 2011 20 Years of the Women’s History Network Looking Back - Looking Forward The Women’s Library, London Metropolitan University Keynote Speakers: Kathryn Gleadle, Caroline Bressey Sheila Rowbotham, Sally Alexander, Anna Davin Krista Cowman, Jane Rendall, Helen Meller The conference will look at the past 20 years of writing women’s history, asking the question where are we now? We will be looking at histories of feminism, work in progress, current areas of debate such as religion and perspectives on national and international histories of the women’s movement. The conference will also invite users of The Women’s Library to take part in one strand that will be set in the Reading Room. We would very much like you to choose an object/item, which has inspired your writing and thinking, and share your experience. Conference website: www.londonmet.ac.uk/thewomenslibrary/ aboutthecollections/research/womens-history-network-conference-2011.cfm Further information and a conference call will be posted on the WHN website www.womenshistorynetwork.org Editorial elcome to the spring issue of Women’s History This issue, as usual, also contains a collection of WMagazine. -

Women Spies and Code Breakers Spring 2020

OLLI Presents Women Spies and Code Breakers Spring 2020 Alan Rubin [email protected] Women Spies and Code Breakers 1840: Augusta Ada King WWI: Elizbeth Smith Freedman Code Breaker WWII: Bletchley Park Code Breakers WWII: Agnes Meyer Driscoll Code Breaker WWII: Virginia Hall Spy WWII: Madame Fourcade Spy WWII: Odette Sansom Spy Post Cold War: Amaryllis Fox: CIA Agent Week 3 • Comments from class members. • Use of Girls vs Women. • J. Edger Hoover, General Charles De Gaulle and women. • --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- • Marie-Madeleine Fourcade. • Why have we not heard about her? • Not a hero but a heroine. • Her team. • Key members of her network 3,000 strong Alliance network. • Very few were trained spies. • Nazi’s nicknamed her network Noah’s Arc. • Agents given code names of animals. • Marie-Madeleine was hedgehog. WWII French Zones General Charles De Gaulle--Marshal Philippe Petain • June 18, 1940 Appeal to French on BBC to resist the German occupiers. • Considered the beginning of the French Resistance. • De Gaulle had recently be promoted to rank of Brigadier General. • “How can I rule a country with so many chiefs?” • Marshall Petain—WWI hero. • Named Prime Minister after PM Paul Reynaud resigned. • De Gaulle opposed Petain and was forced to flee France on June 17, 1940. • Petain became head of Vichy government and pro-Nazi. • Free French Resistance movement started in Vichy area. Marie-Madeleine Fourcade • In December 1940, the operations chief of France’s largest spy The picture can't be displayed. network walked into a bar in the port city of Marseille to recruit a source. • The potential recruit was named Gabriel Rivière. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

Complete Film Noir

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 18 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) dThe idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled almost twenty years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

Download (2631Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/58603 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. A Special Relationship: The British Empire in British and American Cinema, 1930-1960 Sara Rose Johnstone For Doctorate of Philosophy in Film and Television Studies University of Warwick Film and Television Studies April 2013 ii Contents List of figures iii Acknowledgments iv Declaration v Thesis Abstract vi Introduction: Imperial Film Scholarship: A Critical Review 1 1. The Jewel in the Crown in Cinema of the 1930s 34 2. The Dark Continent: The Screen Representation of Colonial Africa in the 1930s 65 3. Wartime Imperialism, Reinventing the Empire 107 4. Post-Colonial India in the New World Order 151 5. Modern Africa according to Hollywood and British Filmmakers 185 6. Hollywood, Britain and the IRA 218 Conclusion 255 Filmography 261 Bibliography 265 iii Figures 2.1 Wee Willie Winkie and Susannah of the Mounties Press Book Adverts 52 3.1 Argentinian poster, American poster, Hungarian poster and British poster for Sanders of the River 86 3.2 Paul Robeson and Elizabeth Welch arriving in Africa in Song of Freedom 92 3.3 Cedric Hardwicke and un-credited actor in Stanley and Livingstone -

Woman of Straw Ending

Woman of straw ending In Woman of Straw (), playing the calculating nephew of Ralph in the playhouses of London's West End. It's thinly populated by stock characters, yet. I can predict the ending of stuff like “Titanic. way ahead of the film “Woman of Straw,” a forgotten British thriller starring Sean Connery. Such is the situation presented with high style in Woman of Straw, up at the end to work things out, and in this case that's Alexander Knox. Crime · Tyrannical but ailing tycoon Charles Richmond becomes very fond of his attractive Italian .. Filming Locations: Audley End House, Saffron Walden, Essex, England, UK See more». IMDb > Woman of Straw () > Reviews & Ratings - IMDb Towards the end, though, his character turns sociopathically chilling, and he hits some good. That is exactly what we have in "Woman of Straw," and you can be certain that Mr. Connery did not No wonder Mr. Connery double-crosses her in the end. I think Connery's downright creepy in WOMAN OF STRAW and I wish he (when mysteries were still that)that kept you guessing until the end. Movie Review – WOMAN OF STRAW (). for this movie, and that's the ending, which came a little too fast and seemed a little too pat to be. Crafty Tony (Sean Connery) is considering whether to bring the sexy new italian nurse Maria (Gina Lollobrigida. There are no critic reviews yet for Woman of Straw. Keep checking If you can withstand the slow start the payoff at the end is well modest. Bond films to star in another fascinating suspense film, Woman of Straw.