Land Guards, State Subordination and Human Rights in Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MODERN DAY SLAVERY in GHANA: WHY APPLICATION..., 13 Rutgers Race & L

MODERN DAY SLAVERY IN GHANA: WHY APPLICATION..., 13 Rutgers Race & L.... 13 Rutgers Race & L. Rev. 169 Rutgers Race & the Law Review Fall 2011 Note Sainabou M. Musa a1 Copyright (c) 2011 Rutgers Race and the Law Review. All rights reserved.; Sainabou M. Musa MODERN DAY SLAVERY IN GHANA: WHY APPLICATION OF UNITED STATES ASYLUM LAWS SHOULD BE EXTENDED TO WOMEN VICTIMIZED BY THE TROKOSI BELIEF SYSTEM Introduction Imagine that it is the year 1998 and you are a slave. Although slavery, in and of itself, may arguably be the worst living condition, imagine that there are different scenarios that could make your life as a slave worse. What would they be? Would it be worse if you were a five-year-old who, for no other reason than the fact that you are a *170 virgin and related to someone who owed a favor to the gods, was subjected to a lifetime of repeated sexual and physical abuse? Maybe your life as a slave would be made worse by knowing that it was your own parents, who for all intents and purposes love you dearly, who assented to you becoming a slave? Would you despair? Or would you pray that someone does something? Let's pretend that you prayed--and that your prayers were answered: the government has outlawed slavery and has stated, quite convincingly, that anyone who forced a child to become a slave would be prosecuted. You are excited; you think, “This is it! I can soon go home and be free.” So you wait. You wait for your master to declare you free. -

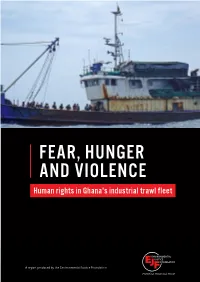

Fear, Hunger and Violence: Human

FEAR, HUNGER AND VIOLENCE Human rights in Ghana's industrial trawl fleet A report produced by the Environmental Justice Foundation 1 OUR MISSION EJF believes environmental security is a human right. EJF strives to: The Environmental Justice Foundation • Protect the natural environment and the people and wildlife (EJF) is a UK-based environmental and human that depend upon it by linking environmental security, human rights charity registered in England and rights and social need Wales (1088128). • Create and implement solutions where they are needed most – 1 Amwell Street training local people and communities who are directly affected London, EC1R 1UL to investigate, expose and combat environmental degradation United Kingdom and associated human rights abuses www.ejfoundation.org • Provide training in the latest video technologies, research and advocacy skills to document both the problems and solutions, This document should be cited as: EJF (2020) working through the media to create public and political Fear, hunger and violence: Human rights in platforms for constructive change Ghana's industrial trawl fleet • Raise international awareness of the issues our partners are working locally to resolve Our Oceans Campaign EJF’s Oceans Campaign aims to protect the marine environment, its biodiversity and the livelihoods dependent upon it. We are working to eradicate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and to create full transparency and traceability within seafood supply chains and markets. We conduct detailed investigations The material has been financed by the Swedish into illegal, unsustainable and unethical practices and actively International Development Cooperation Agency, promote improvements to policy making, corporate governance Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely and management of fisheries along with consumer activism and with the creator. -

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI, GHANA COLLEGE OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY FINGERPRINTING AND CRIMINAL IDENTIFICATION – A CASE STUDY OF ASHANTI REGIONAL CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION DEPARTMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY, FACULTY OF BIOSCIENCE, COLLEGE OF SCIENCE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN FORENSIC SCIENCE BY FRANK OSAE OTCHERE (BSc. Human Resource Management) JUNE, 2019 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor materials which to a substantial extent have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgment is made in the thesis. Frank Osae Otchere ……………………… ………………… (PG1142517) Signature Date Certified by: Dr. Caleb Kesse Frempong ……………………… ………………… (Supervisor) Signature Date Prof. (Mrs.) Antonia Y. Tetteh ……………………… ………………… (Head of Department) Signature Date i DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to the Almighty God, my wife, Mrs. Philomena Osae Otchere (Esq.), and my father, Mr. Emmanuel Osae Otchere. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foremost, I am grateful to God for seeing me through my entire years of graduate school education. He has been the wind beneath my wings. His grace and mercy has brought me this far and I am grateful. My deepest appreciation goes to my supervisor, Dr. Caleb Firempong for his guidance and constructive criticisms that helped me stay focused from the beginning of this research work to the end. -

Nana Akua Anyidoho: Ghana

RIPOCA Research Notes 5-2011 P h ot o: C o l o ur b o x.c o n Nana Akua Anyidoho GHANA Review of Rights Discourse Copyright: The author(s) Ripoca Research Notes is a series of background studies undertaken by authors and team members of the research project Human Rights, Power, and Civic Action (RIPOCA). The project runs from 2008-2012 and is funded by the Norwegian Research Council (project no. 185965/S50). Research application partners: University of Oslo, University of Leeds and Harvard University. The main research output of the Ripoca Project is Human Rights, Power and Civic Action: Comparative Analyses of Struggles for Rights in Developing Societies edited by Bård A. Andreassen and Gordon Crawford and published by Routledge (Spring 2012). Project coordinators: Bård A. Andreassen and Gordon Crawford Research Notes are available on the Project’s website: http://www.jus.uio.no/smr/english/research/projects/ripoca/index.html Any views expressed in this document are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of the partner institutions. GHANA Review of Rights Discourse Nana Akua Anyidoho HUMAN RIGHTS, POWER AND CIVIC ACTION IN DEVELOPING SOCIETIES: COMPARATIVE ANALYSES (RIPOCA) Funded by Norwegian Research Council, Poverty and Peace Research Programme, Grant no.: 185965/S50 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 5 Methodology 5 Organisation of Report 6 CHAPTER ONE 7 FRAMEWORK OF LEGAL RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN PRINCIPLE 7 Legal Commitments to Human Rights in Principle 7 The Constitution 7 Other Domestic/National -

Human Rights Violations Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People in Ghana: a Shadow Report Submitted for Co

Human Rights Violations Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People in Ghana: A Shadow Report Submitted for consideration at the 117th Session of the Human Rights Committee Geneva, June-July 2016 Submitted by: Solace Brothers Foundation The Initiative for Equal Rights Center for International Human Rights of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights Global Initiatives for Human Rights May 2016 Human Rights Violations Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People in Ghana: A Shadow Report I. Introduction This shadow report is submitted to the Human Rights Committee (“Committee”) by Solace Brothers Foundation,1 The Initiative for Equal Rights (“TIERs”)2, the Center for International Human Rights of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, and the Global Initiatives for Human Rights of Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights, in anticipation of the Committee’s consideration at its 117th Session of the Republic of Ghana’s compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“Covenant”).3 The purpose of this report is to direct the Committee’s attention to serious and ongoing violations of the Covenant rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (“LGBT”) individuals by the Republic of Ghana. In particular, this report will focus on the following violations: • Criminalisation of same-sex sexual conduct and the resulting arbitrary arrests and detentions, in violation of Articles 2(1), 9, 17, and 26 of the Covenant; • Violent attacks motivated by the victim’s real or perceived sexual orientation and a pervasive climate of homophobia, in violation of Articles 2(1), 7, 9, 17, and 26 of the Covenant; and • Discrimination in education based upon the victim’s real or perceived sexual orientation, in violation of Articles 2(1) and 26 of the Covenant. -

Ghana @ 60: Governance and Human Rights in Twenty-First Century Africa

GHANA @ 60: GOVERNANCE AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AFRICA Edited by Michael Addaney & Michael Gyan Nyarko 2017 Ghana @ 60: Governance and human rights in twenty-first century Africa Published by: Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) The Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) is a publisher at the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa. PULP endeavours to publish and make available innovative, high-quality scholarly texts on law in Africa. PULP also publishes a series of collections of legal documents related to public law in Africa, as well as text books from African countries other than South Africa. This book was peer reviewed prior to publication. For more information on PULP, see www.pulp.up.ac.za Printed and bound by: BusinessPrint, Pretoria To order, contact: PULP Faculty of Law University of Pretoria South Africa 0002 Tel: +27 12 420 4948 Fax: +27 86 610 6668 [email protected] www.pulp.up.ac.za Cover: Yolanda Booyzen, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria ISBN: 978-1-920538-74-3 © 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments v Foreword vi Abbreviations and acronyms viii Contributors xii List of laws xviii List of cases xxi PART I: INTRODUCTION Governance and human rights in twenty-first 1 century Africa: An introductory appraisal 2 Michael Addaney & Michael Gyan Nyarko PART II: GHANA AT 60 – HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSOLIDATION OF GOOD GOVERNANCE IN A CHALLENGING ERA By accountants and vigilantes: The role of 2 individual actions in the Ghanaian Supreme Court 16 Kenneth NO Ghartey Electoral justice under Ghana’s -

Ghana's Technology Needs Assessment

GHANA’S CLIMATE CHANGE TECHNOLOGY NEEDS AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT REPORT UNDER THE UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE VERSION 1(January 2003) TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE........................................................................................................................................................... IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................................V 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................... IX 2.0 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER IMPLEMENTATION PLAN................................................................1 2.1 ENERGY SECTOR....................................................................................................................................1 2.1.1 OVERVIEW.................................................................................................................................................1 2.1.2 ENERGY EFFICIENT TECHNOLOGIES ..........................................................................................................2 2.1.3 RENEWABLE ENERGY TECHNOLOGIES ......................................................................................................7 2.1.4 SOLAR PHOTOVOLTAIC TECHNOLOGIES ....................................................................................................9 2.1.5 SMALL AND MINI HYDRO........................................................................................................................15 -

Data Collection Survey on Intelligent Transport Systems (Its) in African Region

REPÚBLICA DE HONDURAS SECRETARÍA DE INFRAESTRUCTURA Y SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON INTELLIGENT TRANSPORT SYSTEMS (ITS) IN AFRICAN REGION FINAL REPORT MARCH 2021 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) PADECO CO., LTD. 6R ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. JR 21-008 REPÚBLICA DE HONDURAS SECRETARÍA DE INFRAESTRUCTURA Y SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON INTELLIGENT TRANSPORT SYSTEMS (ITS) IN AFRICAN REGION FINAL REPORT MARCH 2021 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) PADECO CO., LTD. ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. Data Collection Survey on Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) in African Region Final Report Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY page CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES OF THE SURVEY 1.1 Outline of the Survey .................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1.3 Outline of the Survey .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.4 Study Period ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Outline of the Report ................................................................................................................. -

Ghana 2018 Crime & Safety Report

Ghana 2018 Crime & Safety Report According to the current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication, Ghana has been assessed as a “Level 1: Exercise normal precautions” country. However, some areas of the country, including parts of Accra, have increased risk due to crime. Overall Crime and Safety Situation U.S. Embassy Accra does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The American Citizen Services (ACS) Unit cannot recommend a particular individual or location and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. The U.S. Department of State has assessed Accra as being a CRITICAL-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. Please review OSAC’s Ghana-specific page for original analytic reports, consular alerts, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. The Republic of Ghana is a developing country in West Africa. It comprises 10 regions, and the capital is Accra. Tourism can be found in most of the regions, but infrastructure is lacking. Despite a short era of economic growth between 2000 and 2009, the country remains vulnerable to external economic pressures. Crime Threats Street crime is a serious problem throughout the country and is especially acute in Accra and other larger cities. Pickpocketing, purse snatching, and various scams are the most common forms of crime encountered by visitors. U.S. travelers have experienced these crimes in crowded areas. Victims of opportunistic and violent crime are more likely to be targeted based on perceived affluence and/or perceived vulnerability. -

Ghana: State Treatment of LGBTQI+ Persons

Ghana: State treatment of LGBTQI+ persons March 2021 © Asylos and ARC Foundation, 2021 This publication is covered by the Creative Commons License BY-NC 4.0 allowing for limited use provided the work is properly credited to Asylos and ARC Foundation and that it is for non-commercial use. Asylos and ARC Foundation do not hold the copyright to the content of third-party material included in this report. Reproduction or any use of the images/maps/infographics included in this report is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder(s). This report was produced with the kind support of the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Feedback and comments Please help us to improve and to measure the impact of our publications. We would be extremely grateful for any comments and feedback as to how the reports have been used in refugee status determination processes, or beyond, by filling out our feedback form: https://asylumresearchcentre.org/feedback/. Thank you. Please direct any comments or questions to [email protected] and [email protected] Cover photo: © M Four Studio/shutterstock.com 2 Contents 2 CONTENTS 3 EXPLANATORY NOTE 5 BACKGROUND ON THE RESEARCH PROJECT 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 FEEDBACK AND COMMENTS 7 WHO WE ARE 7 LIST OF ACRONYMS 8 RESEARCH TIMEFRAME 9 SOURCES CONSULTED 9 1. LEGAL CONTEXT 13 1.1 CONSTITUTION 13 1.2 CRIMINAL CODE 16 1.3 OTHER RELEVANT LEGISLATION AFFECTING LGBTQI+ PERSONS 20 2. LAW IN PRACTICE 24 2.1 ARRESTS OF LGBTQI+ PERSONS 26 2.1.1 Arrests of gay men 29 2.1.2 Arrests of lesbian women 31 2.1.3 Arrests of cross-dressers 32 2.2 PROSECUTIONS UNDER LAWS THAT ARE DEPLOYED AGAINST LGBTQI+ COMMUNITY BECAUSE OF THEIR PERCEIVED DIFFERENCE 33 2.3 CONVICTIONS UNDER LAWS THAT ARE DEPLOYED AGAINST LGBTQI+ COMMUNITY BECAUSE OF THEIR PERCEIVED DIFFERENCE 36 3. -

INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL TIMBER COUNCIL ITTC(LI)/7 8 October 2015

Distr. GENERAL INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL TIMBER COUNCIL ITTC(LI)/7 8 October 2015 Original: ENGLISH FIFTY-FIRST SESSION 16-21 November 2015 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia PROGRESS REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ITTO THEMATIC PROGRAMMES (Item 13 of the Provisional Agenda) ITTC(LI)/7 Page 1 List of Acronyms ATIBT International Association for Tropical Timber Technologies BWP Biennial Work Programme CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CFME Community Forest Management and Enterprises CFPI Chinese Forest Products Index Mechanism CIRAD International Agronomic Research Cooperation Centre for Development CORPIAA Regional Indigenous Peoples Coordinating Council CTFT Technical Centre for Tropical Forestry DDD Directorate for Sustainable Development, Democratic Republic of Congo DIAF Directorate of Forest Inventory and Management, Democratic Republic of Congo FFPRI Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute FLEGT Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade of the European Union IDE Industrial Development and Efficiency INAB National Institute of Forests, Guatemala ITTC International Tropical Timber Council ITTO International Tropical Timber Organization IUFRO International Union of Forest Research Organizations IWCS Internal Wood Control System JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency MECNT Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism, Democratic Republic of Congo MoU Memorandum of Understanding MP Monitoring Protocol NOL No Objection Letter NTFP Non Timber Forest Products OLMS Online Monitoring System PSC Project Steering Committee -

The Incidence of Domestic Violence Against Women and Children

Online-ISSN 2411-2933, Print-ISSN 2411-3123 March 2017 The Incidence of Domestic Violence Against Women and Children: An Analysis of Reported Cases Within the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit (Dovvsu) At The Asokwa Police Station in Kumasi-Ghana Dr. Francess Dufie Azumah1 (Corresponding author) Department of Sociology and Social Work Faculty of Social Science Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology KNUST-GHANA Nachinaab John Onzaberigu2 Department of Sociology and Social Work Faculty of Social Science Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology KNUST-GHANA MENSAH MANFRED3 Department of Sociology and Social Work Faculty of Social Science Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology KNUST-GHANA Abstract The incidence of domestic violence is a source of great worry to society at large. Victims are suffering while perpetrators seem to be enjoying the act. While children and women are been abused at homes and domestic settings, authorities responsible to protect and safeguard themselves show gross reluctant in their operations and measures to help victims of domestic violence. This is an act serious violation of human right calls for empirical investigation on reported cases of domestic violence against women with the domestic violence and victims support unit at the Asokwa Police station in Kumasi-Ghana. The study sought to identify the major causes of domestic violence at victims’ home, the effects of domestic violence on women and children and ways to curb domestic violence against women and children. The study adopted a case study design where data was collected through questionnaire and victims’ records on reported domestic violence. The study revealed that domestic violence has negative effects on victims as respondents indicated that they suffered from injuries, guilt, anger, depression/anxiety, shyness, nightmares, disruptiveness, irritability, and problems getting along with others.