Nana Akua Anyidoho: Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DPI Associated Ngos - As of September 2011

DPI Associated NGOs - As of September 2011 8Th Day Center For Justice 92St.Y A Better World AARP Abantu For Development Academia Mexicana De Derecho Internacional Academic Council On The United Nations System Academy For Future Science Academy Of Breastfeeding Medicine Academy Of Criminal Justice Sciences Academy Of Fine Arts And Literature Access To Information Programme Foundation Acronym Institute For Disarmament Diplomacy, The Action Against Hunger-Usa Action Aides Aux Familles Demunies Action Internationale Contre La Faim Adelphi University Aegis Trust Africa Faith And Justice Network Africa Genetics Association African Action On Aids African American Islamic Institute African Braille Center African Citizens Development Foundation African Human Rights Heritage African Initiative On Ageing African Medical And Research Foundation, Inc. African Peace Network African Projects/Foundation For Peace And Love Initiatives African Youth Movement Afro-Asian Peoples' Solidarity Organization AFS Inter-Cultural Programs, Inc. Aging Research Center Agudath Israel World Organization Ai. Bi. Associazione Amici Dei Bambini AIESEC International Airline Ambassadors International, Inc. Albert Schweitzer Fellowship Alcohol Education And Rehabilitation Foundation Alfabetizacao Solidaria Alianza Espiritualista Internacional All India Human Rights Association All India Women's Conference All Pakistan Women's Association Alliance For Communities In Action List of DPI-Associated NGOs – September 2011 Alliance Internationale -

MODERN DAY SLAVERY in GHANA: WHY APPLICATION..., 13 Rutgers Race & L

MODERN DAY SLAVERY IN GHANA: WHY APPLICATION..., 13 Rutgers Race & L.... 13 Rutgers Race & L. Rev. 169 Rutgers Race & the Law Review Fall 2011 Note Sainabou M. Musa a1 Copyright (c) 2011 Rutgers Race and the Law Review. All rights reserved.; Sainabou M. Musa MODERN DAY SLAVERY IN GHANA: WHY APPLICATION OF UNITED STATES ASYLUM LAWS SHOULD BE EXTENDED TO WOMEN VICTIMIZED BY THE TROKOSI BELIEF SYSTEM Introduction Imagine that it is the year 1998 and you are a slave. Although slavery, in and of itself, may arguably be the worst living condition, imagine that there are different scenarios that could make your life as a slave worse. What would they be? Would it be worse if you were a five-year-old who, for no other reason than the fact that you are a *170 virgin and related to someone who owed a favor to the gods, was subjected to a lifetime of repeated sexual and physical abuse? Maybe your life as a slave would be made worse by knowing that it was your own parents, who for all intents and purposes love you dearly, who assented to you becoming a slave? Would you despair? Or would you pray that someone does something? Let's pretend that you prayed--and that your prayers were answered: the government has outlawed slavery and has stated, quite convincingly, that anyone who forced a child to become a slave would be prosecuted. You are excited; you think, “This is it! I can soon go home and be free.” So you wait. You wait for your master to declare you free. -

7-Declaration De Dakar 12 Oct

The Dakar Commitment adopted at the 7th Consultation of Women ‘s NGOs We, Civil Society Organizations from all over Africa, comprising : the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), Africa Leadership Forum (ALF), Femme Africa Solidarité (FAS) Foundation for Community Development (FCD), FEMNET, WILDAF, ACDHRS, WAWA, MARWOPNET, ATM, EBWA, Akina Mama Wa Africa, AWA, FAWE, Equality Now, ABANTU, AAWORD, NPI, SSWC, ANSEDI, Pan African Movement, CAFOB; Building upon the important work and achievements accomplished by African women’s networks under the initiative of the African Women Committee for Peace and Development (AWCPD) and Femmes Africa Solidarité (FAS) during previous consultative meetings in Durban in June 2002, in Dakar in April 2003, in Maputo in June 200, in Addis Ababa in June 2004, in Abuja in January 2005 and in Tripoli, in July 2005, in partnership with the AU and ECA, supported by UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNHCR, UNIFEM, OSIWA and other partners. Meeting at the 7th Consultative meeting on Gender Mainstreaming in the African Union (AU) in Dakar, Senegal, prior to the 1st AU Conference of Ministers responsible for Women and Gender that will take place from the 12th to the 16th of October 2005, in order to strengthen our contribution in the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa (SDGEA). Recall the commitment of the African Heads of State to gender equality as a major goal of the AU as enshrined in Article 4 (1) of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, in particular the decision to implement and uphold the principle of gender parity both at regional and national level, as well as the Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa. -

Women Citizenship and Participatory Democracy in Developmental States in Africa: the Case of Kenya

Creating African Futures in an Era of Global Transformations: Challenges and Prospects Créer l’Afrique de demain dans un contexte de transformations mondialisées : enjeux et perspectives Criar Futuros Africanos numa Era de Transformações Globais: Desafios e Perspetivas بعث أفريقيا الغد في سياق التحوﻻت المعولمة : رهانات و آفاق Women Citizenship and Participatory Democracy in Developmental States in Africa: The Case of Kenya Felicia Yieke Women Citizenship and Participatory Democracy in Developmental States in Africa: The Case of Kenya Abstract There has been advocacy of equal rights and opportunities for women, and especially in the extension of women’s activities into the social, economic and political life. Indeed, there is a poor record of historical reflections on the relations between women and politics in African countries, at least in comparison with the abundant scientific production on the same in the Western world. Women’s access to power and active citizenship has thus been one of the main concerns of people who have been interested in a just and democratic society based on equality and social justice. However, it later became apparent that the political vote alone did not ensure women’s full access to the public sphere. This is because the majority of positions of power in education, business and politics have still been occupied by men. What this means is that women are still marginalised as far as access to democratic power is concerned. The room for expanding women’s representation and for sustaining a political focus on women’s issues has varied widely and is dependent on economic, historical and cultural factors as well as the effect of changing international norms. -

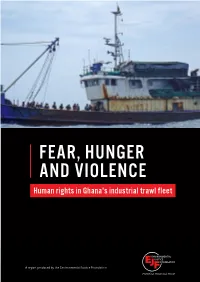

Fear, Hunger and Violence: Human

FEAR, HUNGER AND VIOLENCE Human rights in Ghana's industrial trawl fleet A report produced by the Environmental Justice Foundation 1 OUR MISSION EJF believes environmental security is a human right. EJF strives to: The Environmental Justice Foundation • Protect the natural environment and the people and wildlife (EJF) is a UK-based environmental and human that depend upon it by linking environmental security, human rights charity registered in England and rights and social need Wales (1088128). • Create and implement solutions where they are needed most – 1 Amwell Street training local people and communities who are directly affected London, EC1R 1UL to investigate, expose and combat environmental degradation United Kingdom and associated human rights abuses www.ejfoundation.org • Provide training in the latest video technologies, research and advocacy skills to document both the problems and solutions, This document should be cited as: EJF (2020) working through the media to create public and political Fear, hunger and violence: Human rights in platforms for constructive change Ghana's industrial trawl fleet • Raise international awareness of the issues our partners are working locally to resolve Our Oceans Campaign EJF’s Oceans Campaign aims to protect the marine environment, its biodiversity and the livelihoods dependent upon it. We are working to eradicate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and to create full transparency and traceability within seafood supply chains and markets. We conduct detailed investigations The material has been financed by the Swedish into illegal, unsustainable and unethical practices and actively International Development Cooperation Agency, promote improvements to policy making, corporate governance Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely and management of fisheries along with consumer activism and with the creator. -

Human Rights Violations Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People in Ghana: a Shadow Report Submitted for Co

Human Rights Violations Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People in Ghana: A Shadow Report Submitted for consideration at the 117th Session of the Human Rights Committee Geneva, June-July 2016 Submitted by: Solace Brothers Foundation The Initiative for Equal Rights Center for International Human Rights of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights Global Initiatives for Human Rights May 2016 Human Rights Violations Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People in Ghana: A Shadow Report I. Introduction This shadow report is submitted to the Human Rights Committee (“Committee”) by Solace Brothers Foundation,1 The Initiative for Equal Rights (“TIERs”)2, the Center for International Human Rights of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, and the Global Initiatives for Human Rights of Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights, in anticipation of the Committee’s consideration at its 117th Session of the Republic of Ghana’s compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“Covenant”).3 The purpose of this report is to direct the Committee’s attention to serious and ongoing violations of the Covenant rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (“LGBT”) individuals by the Republic of Ghana. In particular, this report will focus on the following violations: • Criminalisation of same-sex sexual conduct and the resulting arbitrary arrests and detentions, in violation of Articles 2(1), 9, 17, and 26 of the Covenant; • Violent attacks motivated by the victim’s real or perceived sexual orientation and a pervasive climate of homophobia, in violation of Articles 2(1), 7, 9, 17, and 26 of the Covenant; and • Discrimination in education based upon the victim’s real or perceived sexual orientation, in violation of Articles 2(1) and 26 of the Covenant. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276087553 Truncation of SOme Akan Personal Names Article in Gema Online Journal of Language Studies · February 2015 DOI: 10.17576/GEMA-2015-1501-09 CITATION READS 1 180 1 author: Kwasi Adomako University of Education, Winneba 8 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Akan loanwords in Ga-Dangme sub-family View project All content following this page was uploaded by Kwasi Adomako on 31 May 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 143 Volume 15(1), February 2015 Truncation of Some Akan Personal Names Kwasi Adomako [email protected] University of Education, Winneba, Ghana ABSTRACT This paper examines some morphophonological processes in Akan personal names with focus on the former process. The morphological processes of truncation of some indigenous personal names identified among the Akan (Asante) ethnic group of Ghana are discussed. The paper critically looks at some of these postlexical morpheme boundary processes in some Akan personal names realized in the truncated form when two personal names interact. In naming a child in a typical Akan, specifically in Asante‟s custom, a family name is given to the child in addition to his/her „God-given‟ name or day-name. We observe truncation and some phonological processes such as vowel harmony, compensatory lengthening, etc. at the morpheme boundaries in casual speech context. These morphophonological processes would be analyzed within the Optimality Theory framework where it would be claimed that there is templatic constraint that demands that the base surname minimally surfaces as disyllable irrespective of the syllable size of the base surname. -

Historicising the Women's Manifesto for Ghana

Amoah-Boampong, C./ Historicising The Women’s Manifesto for Ghana DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v29i2.2 Historicising The Women’s Manifesto for Ghana: A culmination of women’s activism in Ghana Cyrelene Amoah-Boampong Senior Lecturer Department of History University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: April 13, 2018/ Accepted: October 20, 2018 / Published: December 3, 2018 Abstract Women are one of Ghana’s hidden growth resources. Yet, Ghanaian women have been marginalized from the developmental discourse by a succession of hegemonic political administrations. At best, Ghanaian women were said to have a quiet activism, although each epoch had its own character of struggle. Bringing together history, gender and development, this article examines the historical trajectory of female agency in post- colonial Ghana. It argues that through the historisation of women’s activism, Ghanaian women’s agency and advocacy towards women’s rights and gender equality concerns rose from the era of quiet activism characterised by women’s groups whose operations hardly questioned women’s social status to contestation with the state epitomized by the creation of The Women’s Manifesto for Ghana in 2004 which played a critical role in women’s collective organisation and served as a key pathway of empowerment. Keywords: women, activism, empowerment, Women’s Manifesto, Ghana Introduction Globally, there exists gender disparities in human development. According to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, gender equality is fundamental to delivering on the promises of sustainability, peace and human progress (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2016). Ghana adopted all 17 goals set to end poverty and ensure prosperity for all. -

Abantu for Development Uganda (AFOD)

E WIPO/GRTKF/IC/12 /2 ORIGINAL: English WIPO DATE: December 7, 2007 WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION GENEVA INTERGOVERNMENTAL CO MMITTEE ON INTELLECTUAL PROPERT Y AND GENETIC RESOUR CES, TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDG E AND FOLKLORE Twelf th Session Gen eva, February 25 to 29, 2008 ACCREDITATION OF CER TAIN ORGANIZATIONS Document prepared by the Secretariat 1. The Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (“the Committee”), at its first session, held in Geneva, from April 30 to May 3, 2001, approved certain organizational and procedural matters, including according ad hoc observer status to a number of organizations that had expressed their wish to have a role in the works of the Committee (see the Report adopted by the Committee, WIPO/GRKTF/IC/1/13, paragraph 18). 2. Since then, an additional number of organizations have expressed to the Secretariat their wish to obtain the same status for the subsequent sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee. A document containing the names and other biographical details of the organizations which, before December 6, 2007, requested representation in the twelf th session of the Intergovernmental Committee is annexed to this document. The biographica l details on the organizations contained in the Annex were received from each organization. 3. The Intergovernmental Committee is invited to approve the accreditation of the organizations referred to in the Annex to this document as ad hoc observers. [An nex follows] WIPO/GRTKF/IC/12/2 -

Ghana @ 60: Governance and Human Rights in Twenty-First Century Africa

GHANA @ 60: GOVERNANCE AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AFRICA Edited by Michael Addaney & Michael Gyan Nyarko 2017 Ghana @ 60: Governance and human rights in twenty-first century Africa Published by: Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) The Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) is a publisher at the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa. PULP endeavours to publish and make available innovative, high-quality scholarly texts on law in Africa. PULP also publishes a series of collections of legal documents related to public law in Africa, as well as text books from African countries other than South Africa. This book was peer reviewed prior to publication. For more information on PULP, see www.pulp.up.ac.za Printed and bound by: BusinessPrint, Pretoria To order, contact: PULP Faculty of Law University of Pretoria South Africa 0002 Tel: +27 12 420 4948 Fax: +27 86 610 6668 [email protected] www.pulp.up.ac.za Cover: Yolanda Booyzen, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria ISBN: 978-1-920538-74-3 © 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments v Foreword vi Abbreviations and acronyms viii Contributors xii List of laws xviii List of cases xxi PART I: INTRODUCTION Governance and human rights in twenty-first 1 century Africa: An introductory appraisal 2 Michael Addaney & Michael Gyan Nyarko PART II: GHANA AT 60 – HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSOLIDATION OF GOOD GOVERNANCE IN A CHALLENGING ERA By accountants and vigilantes: The role of 2 individual actions in the Ghanaian Supreme Court 16 Kenneth NO Ghartey Electoral justice under Ghana’s -

Biography of an African Community, Culture, and Nation

Biography of an African Kwasi Konadu Community, Culture, & Nation OUR OWN WAY IN THIS PART OF THE WORLD OUR OWN WAY IN THIS PART OF Biography of an African THE WORLD Community, Culture, and Nation Duke University Press DurhamDurham and London © . All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Avenir and Arno Pro by Westester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Konadu, Kwasi, author. Title: Our own way in this part of the world : biography of an African culture, community, and nation / Kwasi Konadu. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, . | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identiers: (print) | (ebook) (ebook) (hardcover : alk. paper) (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: : Donkor, Ko, Nana, – . | HealersGhana Biography. | Traditional medicineGhana. | GhanaHistoryTo . | DecolonizationGhana. | GhanaSocial life and customs. Classication: . (ebook) | . (print) | . []dc record available at hps://lccn.loc.gov/ Cover art: Ko Dↄnkↄ carry inging the Asubↄnten Kwabena shrine at the TTakyimanakyiman Foe Festival, October . From the Dennis Michael Warren Slide Collection, Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries. To the lives and legacies of Ko Dɔnkɔ, Adowa Asabea (Akumsa), Akua Asantewaa, Ko Kyereme, Yaw Mensa, and Ko Ɔboɔ [For those] in search of past events and maers connected with our culture as well as maers about you, the [abosom, “spiritual forces,” I . .] will also let them know clearly how we go about things in our own way in this part of the world. Nana Ko Dɔnkɔ Acknowledgments ix Introduction . Libation “ Maers Connected with Our Culture” . Homelands “In Search of Past Events” .