Ghana's Transition to Constitutional Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workshop on Strengthening the Collection and Use of International Migration Data for Development

Workshop on Strengthening the Collection and Use of International Migration Data For Development Topic: The international migration and development agenda: Implications for data collection A Presentation By Godwin O. Gyebi & Noah A. Yeboah VENUE: United Nations Conference Center Addis Ababa, Ethiopia th DATE: Tuesday, 19 November, 2014 1 Presentation Outline Over view of migration data in Ghana Enhancing the benefits of international migration for national development Data needed to evaluate policies On-going migration management programs Ghana Integrated Migration Management Approach (GIMMA) - the comprehensive database to manage international migration data. 2 Over view of migration data in Ghana • Internal and international migration continue to present both challenges and opportunities to Ghana. Either regular or irregular, migration continue to have a direct impact on the economy of Ghana over time. • Ghana has an active diaspora community, which has historically demonstrated an a strong commitment to homeland development and continue to contribute to the socio-economic development of Ghana. • In recognising this, the Ghana Medium Term Development Plan, Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (201-2013) and other programs link effective migration management to national development. 3 Ghana’s policy on migration Indeed, migration management in Ghana is carried out through a range of rights and freedoms enshrined in the 1992 constitution, Acts of Parliament and other National regulations Migration Governance in Ghana is further -

Building on Custom: Land Tenure Policy and Economic Development in Ghana

BLOCHER 6.20.DOC 6/20/2006 3:29 PM Note Building on Custom: Land Tenure Policy and Economic Development in Ghana Joseph Blocher† This Note addresses the intersection of customary and statutory land law in the land tenure policy of Ghana. It argues that improving the current land tenure policy demands integration of customary land law and customary authorities into the statutory system. After describing why and how customary property practices are central to the economic viability of any property system, the Note gives a brief overview of Ghana’s customary and statutory land law. The Note concludes with specific policy suggestions about how Ghana could better draw on the strength of its customary land sector. INTRODUCTION Land makes up nearly three quarters of the wealth of developing countries,1 and development leaders,2 businesspeople,3 and academics4 † B.A., Rice University, MPhil, Cambridge University, J.D. candidate, Yale Law School. Thanks to John Bruce, Martin Dixon, Daniel Fitzpatrick, and Gordon Woodman, and to the exceptionally able editors of the Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal, especially Raquiba Huq, Mollie Lee, and Adam Romero. The initial research for this paper was performed in Ghana with the support of the Fulbright Commission, and at the Department of Land Economy at Cambridge University with the support of the Gates Cambridge Trust. 1. HERNANDO DE SOTO, THE MYSTERY OF CAPITAL 86 (2000). 2. The World Bank’s 2002 development report was clear in its support for property rights as a prerequisite for economic growth. See THE WORLD BANK, BUILDING INSTITUTIONS FOR MARKETS 34-38 (2002) (discussing land rights). -

The Effect of Article 78 (1) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana on the Oversight Role of the Parliament of Ghana

THE EFFECT OF ARTICLE 78 (1) OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION OF GHANA ON THE OVERSIGHT ROLE OF THE PARLIAMENT OF GHANA By Michael Amoateng [B.A. Stat. and Econs. (Hons.)] A Thesis submitted to the Institute of Distance Learning Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Commonwealth Executive Master of Public Administration Institute of Distance Learning SEPTEMBER 2012 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the Commonwealth Executive Master of Public Administration and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgements have been made in the text. ……………………………………… ……………………… …………………… Student Name & ID Signature Date Certified by: ………………………………………. …………………… …………………….. Supervisor’s Name Signature Date Certified by: ……………………………….. ………………………… ……………………. Head of Depart. Name Signature Date ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to the Almighty God, my lovely and treasured better-half, Mrs. Christiana Konadu Amoateng, my shrewd and cherished daughter, Ms. Christiana Konadu Amoateng, my astute and dearest sister, Mrs. Mercy Efia Boatemaa Owusu- Agyei and my entire family for their indefatigable support and prayers for me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my profound gratitude to the Almighty God for his protection and guidance and for granting me favour and divine authority to complete this project. My astute better-half, Mrs. Christiana Konadu Amoateng deserves very special mention for her love and understanding. Particular thanks are owed to my supervisor, Mr. Samuel Kwasi Enninful for his wonderful and relentless guidance, direction and patience which brought this project to a successful completion. -

MODERN DAY SLAVERY in GHANA: WHY APPLICATION..., 13 Rutgers Race & L

MODERN DAY SLAVERY IN GHANA: WHY APPLICATION..., 13 Rutgers Race & L.... 13 Rutgers Race & L. Rev. 169 Rutgers Race & the Law Review Fall 2011 Note Sainabou M. Musa a1 Copyright (c) 2011 Rutgers Race and the Law Review. All rights reserved.; Sainabou M. Musa MODERN DAY SLAVERY IN GHANA: WHY APPLICATION OF UNITED STATES ASYLUM LAWS SHOULD BE EXTENDED TO WOMEN VICTIMIZED BY THE TROKOSI BELIEF SYSTEM Introduction Imagine that it is the year 1998 and you are a slave. Although slavery, in and of itself, may arguably be the worst living condition, imagine that there are different scenarios that could make your life as a slave worse. What would they be? Would it be worse if you were a five-year-old who, for no other reason than the fact that you are a *170 virgin and related to someone who owed a favor to the gods, was subjected to a lifetime of repeated sexual and physical abuse? Maybe your life as a slave would be made worse by knowing that it was your own parents, who for all intents and purposes love you dearly, who assented to you becoming a slave? Would you despair? Or would you pray that someone does something? Let's pretend that you prayed--and that your prayers were answered: the government has outlawed slavery and has stated, quite convincingly, that anyone who forced a child to become a slave would be prosecuted. You are excited; you think, “This is it! I can soon go home and be free.” So you wait. You wait for your master to declare you free. -

Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments Through 1996

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 constituteproject.org Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 1996 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 Table of contents Preamble . 14 CHAPTER 1: THE CONSTITUTION . 14 1. SUPREMACY OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 2. ENFORCEMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 3. DEFENCE OF THE CONSTITUTION . 15 CHAPTER 2: TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 4. TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 5. CREATION, ALTERATION OR MERGER OF REGIONS . 16 CHAPTER 3: CITIZENSHIP . 17 6. CITIZENSHIP OF GHANA . 17 7. PERSONS ENTITLED TO BE REGISTERED AS CITIZENS . 17 8. DUAL CITIZENSHIP . 18 9. CITIZENSHIP LAWS BY PARLIAMENT . 18 10. INTERPRETATION . 19 CHAPTER 4: THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 11. THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 CHAPTER 5: FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 Part I: General . 20 12. PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 13. PROTECTION OF RIGHT TO LIFE . 20 14. PROTECTION OF PERSONAL LIBERTY . 21 15. RESPECT FOR HUMAN DIGNITY . 22 16. PROTECTION FROM SLAVERY AND FORCED LABOUR . 22 17. EQUALITY AND FREEDOM FROM DISCRIMINATION . 23 18. PROTECTION OF PRIVACY OF HOME AND OTHER PROPERTY . 23 19. FAIR TRIAL . 23 20. PROTECTION FROM DEPRIVATION OF PROPERTY . 26 21. GENERAL FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS . 27 22. PROPERTY RIGHTS OF SPOUSES . 29 23. ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE . 29 24. ECONOMIC RIGHTS . 29 25. EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS . 29 26. CULTURAL RIGHTS AND PRACTICES . 30 27. WOMEN'S RIGHTS . 30 28. CHILDREN'S RIGHTS . 30 29. RIGHTS OF DISABLED PERSONS . -

The Rawlings' Factor in Ghana's Politics

al Science tic & li P Brenya et al., J Pol Sci Pub Aff 2015, S1 o u P b f l i o c DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.S1-004 l Journal of Political Sciences & A a f n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Public Affairs Research Article Open Access The Rawlings’ Factor in Ghana’s Politics: An Appraisal of Some Secondary and Primary Data Brenya E, Adu-Gyamfi S*, Afful I, Darkwa B, Richmond MB, Korkor SO, Boakye ES and Turkson GK Department of History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana Abstract Global concern for good leadership and democracy necessitates an examination of how good governance impacts the growth and development of a country. Since independence, Ghana has made giant strides towards good governance and democracy. Jerry John Rawlings has ruled the country for significant period of the three decades. Rawlings emerged on the political scene in 1979 through coup d’état as a junior officer who led the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) and eventually consolidated his rule as a legitimate democratically elected President of Ghana under the fourth republican constitution in 1992. Therefore, Ghana’s political history cannot be complete without a thorough examination of the role of the Rawlings in the developmental/democratic process of Ghana. However, there are different contentions about the impact of Rawlings on the developmental and democratic process of Ghana. This study examines the impacts of Rawlings’ administration on the politics of Ghana using both qualitative and quantitative analytical tools. -

World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems

WORLD FACTBOOK OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS Ghana by Obi N.I. Ebbe State University of New York at Brockport This country report is one of many prepared for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems under Grant No. 90-BJ-CX-0002 from the Bureau of Justice Statistics to the State University of New York at Albany. The project director for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice was Graeme R. Newman, but responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in each report is that of the individual author. The contents of these reports do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the U.S. Department of Justice. GENERAL OVERVIEW I. Political System. Ghana has a multi-party parliamentary government with an elected President who is both Chief of the executive branch and the Head of State. Ghana has a centralized government with local divisions in eleven regions. There is a single legislature in the country, consisting of the President and the National Assembly. Regional leaders report to the central government in the capital of Accra. The criminal justice system is centralized in that the government has control over the courts, prisons, judges, and police. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Inspector General of Police, and the Director of Prisons are all appointed by the government and serve the entire country. Ghana is a member of the organization for African Unity (OAU) and a member of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). It joined the British commonwealth in 1960. 2. -

Voting Pattern and Electoral Alliances in Ghana's 1996 Elections

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Afr. i. polit. sci. (1997). Vol. 2 No. 2. 38-52 Voting Pattern and Electoral Alliances in Ghana's 1996 Elections Felix K. G.Anebo* Abstract In the 1996 presidential and parliamentary elections, Ghana's two major opposi- tion political parties - the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and People's Convention Party (PCP) - which are traditionally very bitter opponents, formed an electoral alliance to defeat Rowlings and his National Democratic Congress. This paper analyses the factors that influenced the electoral alliance of the two traditional antagonists, and explains the reasons for their failure, in spite of their alliance, to win the elections. It argues, among other things, that changes in existing political alignments as well as voting patterns accounts for the electoral victory of Rowlings and his NDC in the elections. Introduction Common opposition to the Rawlings regime has made possible electoral co- operation between the country' s two major political antagonists, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and People's Convention Party (PCP). In whatever way it is viewed, the electoral alliance between the NPP and PCP into what they refer to as "The Great Alliance" is politically very significant. The two parties come from two divergent political traditions and were historically bitter enemies. The PCP traces its ancestry to Kwame Nkrumah's Convention People's Party (CPP) which in its hey days was associated with radical nationalism, Pan-Africanism and socialism. -

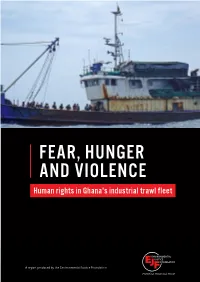

Fear, Hunger and Violence: Human

FEAR, HUNGER AND VIOLENCE Human rights in Ghana's industrial trawl fleet A report produced by the Environmental Justice Foundation 1 OUR MISSION EJF believes environmental security is a human right. EJF strives to: The Environmental Justice Foundation • Protect the natural environment and the people and wildlife (EJF) is a UK-based environmental and human that depend upon it by linking environmental security, human rights charity registered in England and rights and social need Wales (1088128). • Create and implement solutions where they are needed most – 1 Amwell Street training local people and communities who are directly affected London, EC1R 1UL to investigate, expose and combat environmental degradation United Kingdom and associated human rights abuses www.ejfoundation.org • Provide training in the latest video technologies, research and advocacy skills to document both the problems and solutions, This document should be cited as: EJF (2020) working through the media to create public and political Fear, hunger and violence: Human rights in platforms for constructive change Ghana's industrial trawl fleet • Raise international awareness of the issues our partners are working locally to resolve Our Oceans Campaign EJF’s Oceans Campaign aims to protect the marine environment, its biodiversity and the livelihoods dependent upon it. We are working to eradicate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and to create full transparency and traceability within seafood supply chains and markets. We conduct detailed investigations The material has been financed by the Swedish into illegal, unsustainable and unethical practices and actively International Development Cooperation Agency, promote improvements to policy making, corporate governance Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely and management of fisheries along with consumer activism and with the creator. -

ACCOUNTING to the PEOPLE #Changinglives #Transformingghana H

ACCOUNTING TO THE PEOPLE #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana H. E John Dramani Mahama President of the Republic of Ghana #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana 5 FOREWORD President John Dramani Mahama made a pact with the sovereign people of Ghana in 2012 to deliver on their mandate in a manner that will change lives and transform our dear nation, Ghana. He has been delivering on this sacred mandate with a sense of urgency. Many Ghanaians agree that sterling results have been achieved in his first term in office while strenuous efforts are being made to resolve long-standing national challenges. PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST This book, Accounting to the People, is a compilation of the numerous significant strides made in various sectors of our national life. Adopting a combination of pictures with crisp and incisive text, the book is a testimony of President Mahama’s vision to change lives and transform Ghana. EDUCATION The book is presented in two parts. The first part gives a broad overview of this Government’s performance in various sectors based on the four thematic areas of the 2012 NDC manifesto.The second part provides pictorial proof of work done at “Education remains the surest path to victory the district level. over ignorance, poverty and inequality. This is self evident in the bold initiatives we continue to The content of this book is not exhaustive. It catalogues a summary of President take to improve access, affordability, quality and Mahama’s achievements. The remarkable progress highlighted gives a clear relevance at all levels.” indication of the President’s committment to changing the lives of Ghanaians and President John Dramani Mahama transforming Ghana. -

Cocoa Sector in Ghana Indd.Indd

Labor practices in the cocoa sector of Ghana with a special focus on the role of children Findings from a 2001 survey of cocoa producing households Olivia Abenyega and James Gockowski Institute of Renewable Natural Resources, (KNUST) Kumasi International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) with the assistance and collaboration of: International Labor Organization (ILO) i Executive summary A baseline survey of the major cocoa-growing regions in Ghana was conducted to provide information necessary for the implementation of the Sustainable Tree Crops Program (STCP). It forms part of activities that were approved during the regional STCP imple- mentation workshop held from 22 to 26 May 2000 in Accra, Ghana. The survey was conducted in the four major producing regions of Ghana which are the Western, Brong Afaho, Ashanti, and Eastern regions. In mid-2001, accounts of slavery-like practices and trafficking involving children on cocoa plantations of Côte d’Ivoire were reported in the media. To assist in addressing this highly complex issue, the STCP solicited the expertise of the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labor (IPEC) of the International Labor Organization (ILO). Given this new context, the labor practices section of the STCP baseline survey was significantly amended and expanded to address the issue of child labor and implemented in the field from October to November 2001. The specific objectives of the survey on child labor are: • To determine the type, extent, and magnitude of child labor utilized in the cocoa sectors of Cameroon, Nigeria, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire with a particular regard to the issues raised in Articles 3(a) and 3(d) of ILO Convention 182. -

Nana Akua Anyidoho: Ghana

RIPOCA Research Notes 5-2011 P h ot o: C o l o ur b o x.c o n Nana Akua Anyidoho GHANA Review of Rights Discourse Copyright: The author(s) Ripoca Research Notes is a series of background studies undertaken by authors and team members of the research project Human Rights, Power, and Civic Action (RIPOCA). The project runs from 2008-2012 and is funded by the Norwegian Research Council (project no. 185965/S50). Research application partners: University of Oslo, University of Leeds and Harvard University. The main research output of the Ripoca Project is Human Rights, Power and Civic Action: Comparative Analyses of Struggles for Rights in Developing Societies edited by Bård A. Andreassen and Gordon Crawford and published by Routledge (Spring 2012). Project coordinators: Bård A. Andreassen and Gordon Crawford Research Notes are available on the Project’s website: http://www.jus.uio.no/smr/english/research/projects/ripoca/index.html Any views expressed in this document are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of the partner institutions. GHANA Review of Rights Discourse Nana Akua Anyidoho HUMAN RIGHTS, POWER AND CIVIC ACTION IN DEVELOPING SOCIETIES: COMPARATIVE ANALYSES (RIPOCA) Funded by Norwegian Research Council, Poverty and Peace Research Programme, Grant no.: 185965/S50 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 5 Methodology 5 Organisation of Report 6 CHAPTER ONE 7 FRAMEWORK OF LEGAL RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN PRINCIPLE 7 Legal Commitments to Human Rights in Principle 7 The Constitution 7 Other Domestic/National