Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 12:45:59PM Via Free Access the Dangers of ‘Warming and Replenishing’ 91

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Results Announcement for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

(GDR under the symbol "HTSC") RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Huatai Securities Co., Ltd. (the "Company") hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement contains the full text of the annual results announcement of the Company for 2020. PUBLICATION OF THE ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE ANNUAL REPORT This results announcement of the Company will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism), and the website of the Company (www.htsc.com.cn), respectively. The annual report of the Company for 2020 will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of the National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism) and the website of the Company in due course on or before April 30, 2021. DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in the annual report of the Company for 2020 as set out in this announcement. By order of the Board Zhang Hui Joint Company Secretary Jiangsu, the PRC, March 23, 2021 CONTENTS Important Notice ........................................................... 3 Definitions ............................................................... 6 CEO’s Letter .............................................................. 11 Company Profile ........................................................... 15 Summary of the Company’s Business ........................................... 27 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board ....................... 40 Major Events.............................................................. 112 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders .................................... 149 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff.............................. -

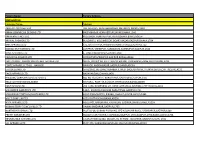

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List

LEVI STRAUSS & CO. FACTORY LIST Published : September 2014 Country Factory name Alternative factory name Address City State/Province Argentina Accecuer SA Juan Zanella 4656 Caseros Buenos Aires Avanti S.A. Coronel Suarez 1544 Olavarría Buenos Aires Best Sox S.A. Charlone 1446 Capital Federal Buenos Aires Buffalo S.R.L. Valentín Vergara 4633 Florida Oeste Buenos Aires Carlos Kot San Carlos 1047 Wilde Buenos Aires CBTex S.R.L. - Cut Avenida de los Constituyentes, 5938 Capital Federal Buenos Aires CBTex S.R.L. - Sew San Vladimiro, 5643 Lanús Oeste Buenos Aires Cooperativa de Trabajo Textiles Pigue Ltda. Altromercato Ruta Nac. 33 Km 132 Pigue Buenos Aires Divalori S.R.L Miralla 2536 Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Estex Argentina S.R.L. Superi, 3530 Caba Buenos Aires Gitti SRL Italia 4043 Mar del Plata Buenos Aires Huari Confecciones (formerly Victor Flores Adrian) Victor Flores Adrian Charcas, 458 Ramos Mejía Buenos Aires Khamsin S.A. Florentino Ameghino, 1280 Vicente Lopez Buenos Aires Ciudad Autonoma de Buenos La Martingala Av. F.F. de la Cruz 2950 Buenos Aires Aires Lenita S.A. Alfredo Bufano, 2451 Capital Federal Buenos Aires Manufactura Arrecifes S.A. Ruta Nacional 8, Kilometro 178 Arrecifes Buenos Aires Materia Prima S.A. - Planta 2 Acasusso, 5170 Munro Buenos Aires Procesadora Centro S.R.L. Francisco Carelli 2554 Venado Tuerto Santa Fe Procesadora Serviconf SRL Gobernardor Ramon Castro 4765 Vicente Lopez Buenos Aires Procesadora Virasoro S.A. Boulevard Drago 798 Pergamino Buenos Aires Procesos y Diseños Virasoro S.A. Avenida Ovidio Lagos, 4650 Rosario Santa Fé Provira S.A. Avenida Bucar, 1018 Pergamino Buenos Aires Spring S.R.L. -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”). -

The Structure and Circulation of the Elite in Late-Tang China

elite in late-tang china nicolas tackett Great Clansmen, Bureaucrats, and Local Magnates: The Structure and Circulation of the Elite in Late-Tang China he predominant paradigm describing Chinese elite society of the T first millennium ad was defined thirty years ago in carefully re- searched studies by Patricia Ebrey and David Johnson, both of whom partly built upon the foundation of earlier scholarship by Takeda Ryˆji 竹田龍兒, Moriya Mitsuo 守屋美都雄, Niida Noboru 仁井田陞, Sun Guodong 孫國棟, Mao Hanguang 毛漢光, and others.1 According to this model, a circumscribed number of aristocratic “great clans” were able to maintain their social eminence for nearly a thousand years while simultaneously coming to dominate the upper echelons of the government bureaucracy. The astonishing longevity of these families was matched in remarkability only by their sudden and complete disap- pearance after the fall of the Tang at the turn of the tenth century. In their place, a new civil-bureaucratic scholar-elite came to the fore, an elite described in enormous detail first by Robert Hartwell and Robert I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments, as well as all of the participants in the 2007 AAS panel where I first presented this paper, notably the discussants Robert Hymes and Beverly Bossler. To minimize the number of footnotes, references for epitaphs of individuals are not included in the main text and notes, but in- stead can be found in the appendix. All tables are located at the end of the article, after the appendix. 1 David Johnson, “The Last Years of a Great Clan: The Li Family of Chao chün in Late T’ang and Early Sung,” H JAS 37.1 (1977), pp. -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

The Korean Monk Sangwŏl (1911-1974) and the Rise of the Ch’Ŏnt’Ae School of Buddhism by © 2017 Yohong Roh B.A., the University of Findlay, 2014

New Wine in an Old Bottle: The Korean Monk Sangwŏl (1911-1974) and the Rise of the Ch’ŏnt’ae school of Buddhism By © 2017 Yohong Roh B.A., The University of Findlay, 2014 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Department of Religious Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Chair: Daniel Stevenson Jacquelene Brinton William R. Lindsey Date Defended: 10 July 2017 ii The thesis committee for Yohong Roh certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: New Wine in an Old Bottle: The Korean Monk Sangwŏl (1911-1974) and the Rise of the Ch’ŏnt’ae school of Buddhism Chair: Daniel Stevenson Date Approved: 10 July 2017 iii Abstract The thesis explores the diverse ways in which a new Korean Buddhist movement that calls itself the “Ch’ŏnt’ae Jong (Tiantai school)” has appropriated and deployed traditional patriarchal narratives of the Chinese Tiantai tradition to legitimize claims to succession of its modern founder, the Korean monk Sangwŏl (1922-1974). Sangwŏl began his community as early as 1945; however, at that time his community simply referred to itself as the “teaching of Sangwŏl” or “teaching of Kuinsa,” after the name of his monastery. It was not until the official change of the name to Ch’ŏnt’ae in 1967 that Korean Buddhists found a comprehensive and identifiable socio-historical space for Sangwŏl and his teaching. Key to that transition was not only his adapting the historically prominent name “Ch’ŏnt’ae,” but his retrospective creation of a lineage of Chinese and Korean patriarchs to whom he could trace his succession and the origin of his school. -

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: on the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628)

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Yungfen Ma All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma This dissertation is a study of Youxi Chuandeng’s (1554-1628) transformation of “Buddha-nature includes good and evil,” also known as “inherent evil,” a unique idea representing Tiantai’s nature-inclusion philosophy in Chinese Buddhism. Focused on his major treatise On Nature Including Good and Evil, this research demonstrates how Chuandeng, in his efforts to regenerate Tiantai, incorporated the important intellectual themes of the late Ming, especially those found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. In his treatise, Chuandeng systematically presented his ideas on doctrinal classification, the principle of nature-inclusion, and the practice of the Dharma-gate of inherent evil. Redefining Tiantai doctrinal classification, he legitimized the idea of inherent evil to be the highest Buddhist teaching and proved the superiority of Buddhism over Confucianism. Drawing upon the notions of pure mind and the seven elements found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra, he reinterpreted nature-inclusion and the Dharma-gate of inherent evil emphasizing inherent evil as pure rather than defiled. Conversely, he reinterpreted the Śūraṃgama Sūtra by nature-inclusion. Chuandeng incorporated Confucianism and the Śūraṃgama Sūtra as a response to the dominating thought of his day, this being the particular manner in which previous Tiantai thinkers upheld, defended and spread Tiantai. -

Admonitions for Women. See Applico.Tion

Index Note: Chinese names and terms are alphabetized by character. Admonitionsfor Women. See Ban Zhao Chen Zhen, 82, 85 Amazon.com, 131-133 Cheng Yi, 173n. 11 Analects (Lunyu) , 8, 14, 20, 30-31, 35, Cheng z.hi wen z.hi, 36, 52, 54, 57; and 49-50, 54, 102, 116-117, 167n. 34 other proposed titles, 17ln. 2. See Applico.tion of Equilibrium ( Zhongyong) , also Guodian manuscripts 14, 21, 117. See also Confucianism Chinese language, 3, 119, 210n. 4. SU archaeology, 3-5 also Old Chinese Aristotle. See Rhetoric Chu (state), 5, 26-27, 56, 66-67, 74, 80-87 passim, 101, 115n. 16 Bai Qi, 190n. 26 Chuci. SeeLyrics of Chu Baihu tong. See White Tiger Hall Chunqiu. See springs and Autumns Ban Gu, 114 Chunyu Kun, 7-8, 157n. 35 Ban Zhao: scholarly opinions of, 112- Chunyu fue, 70 114, 117-118; fu-shih Chen on, Cicero, 76, 86, 196n. 73 113-117 Collections of Sayings ( Yucong) , 36. See Bentham, Jeremy, 82 also Guodian manuscripts Bynner, Witter, 120-121, 125-127, Confucianism, 3, 32, 34-37, 53, 56, 130, 132 89, 131, 197n. 8; and Ban Zhao, 114; in Hu ainanz.i, 90-91, 102- Cangjie, 58-59 104, 111, 203n. 64; texts, 5, 71, Carnal Prayer Mat, 119, 194n. 52 121. See also Analects; Applico.tion Chan, Wing-tsit, 122-130 passim, of Equilibrium; Confucius; Erya; 212n. 32 Great LeaminfJ, Mencius; Ode.s; Changes (Yi), 5, 41, 82, 116, 170n. 69, Ritual &curds; Xunzi 175n. 30 Confucius, 14, 37, 49-50, 72, 84, Chao Gongwu, 191n. -

Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late

Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 ©2015 Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai All rights reserved ABSTRACT Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai This dissertation is the first focused study of images of demons and how they were created and received at the turn of the Southern Song and Yuan periods of China. During these periods, China was in a state of dynastic crisis and transition, and the presence of foreign invaders, the rise of popular culture, the development of popular religion, as well as the advancement of commerce and transportation provided new materials and incentives for painting the supernatural grotesque. Given how widely represented they are in a variety of domains that include politics, literature, theater, and ritual, the Demon Queller Zhong Kui and his demons are good case studies for the effects of new social developments on representations of the supernatural grotesque. Through a careful iconological analysis of three of the earliest extant handscroll paintings that depict the mythical exorcist Zhong Kui travelling with his demonic entourage, this dissertation traces the iconographic sources and uncovers the multivalent cultural significances behind the way grotesque supernatural beings were imagined. Most studies of paintings depicting Zhong Kui focus narrowly on issues of connoisseurship, concentrate on the painter’s intent, and prioritize political metaphors in the paintings. -

Listing of Global Companies with Ongoing Government Activity

COMPANY LINE OF BUSINESS TICKER X F ENTERPRISES, INC. PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XANTE CORPORATION COMPUTER PERIPHERAL EQUIPMENT, NEC XANTHUS LIFE SCIENCES SECURITIES CORPORATION MEDICINALS AND BOTANICALS, NSK XAUBET FRANCISCO BENITO Y QUINTAS JOSE ALBERTO PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XCELIENCE, LLC PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XCELLEREX, INC. BIOLOGICAL PRODUCTS, EXCEPT DIAGNOSTIC XEBEC FORMULATIONS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XELLIA GYOGYSZERVEGYESZETI KORLATOLT FELELOSSEGU TARSASAG PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XELLIA PHARMACEUTICALS APS PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XELLIA PHARMACEUTICALS AS PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XENA BIO HERBALS PRIVATE LIMITED MEDICINALS AND BOTANICALS, NSK XENA BIOHERBALS PRIVATE LIMITED MEDICINALS AND BOTANICALS, NSK XENON PHARMACEUTICALS PRIVATE LIMITED PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XENOPORT, INC. PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XENOTECH, L.L.C. BIOLOGICAL PRODUCTS, EXCEPT DIAGNOSTIC XEPA PHARMACEUTICALS PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XEPA-SOUL PATTINSON (MALAYSIA) SDN BHD PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XEROX AUDIO VISUAL SOLUTIONS, INC. PHOTOGRAPHIC EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES, NSK XEROX CORPORATION OFFICE EQUIPMENT XEROX CORPORATION COMPUTER PERIPHERAL EQUIPMENT, NEC XRX XEROX CORPORATION PHOTOGRAPHIC EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES X-GEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. PHARMACEUTICAL PREPARATIONS XHIBIT SOLUTIONS INC BUSINESS SERVICES, NEC, NSK XI`AN HAOTIAN BIO-ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY CO.,LTD. MEDICINALS AND BOTANICALS, NSK XIA YI COUNTY BELL BIOLOGY PRODUCTS CO., LTD. BIOLOGICAL PRODUCTS, EXCEPT DIAGNOSTIC XIAHUA SHIDA -

University of Hawai'i Library

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY THE FOUR SAINTS INTERCULTURAL EXCHANGE AND THE EVOLUTION OF THEIR ICONOGRAPHY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION (ASIAN) AUGUST 2008 By Ryan B. Brooks Thesis Committee: Poul Andersen, Chairperson Helen Baroni Edward Davis We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion (Asian). THESIS COMMITTEE ii Copyright © 2008 by Ryan Bruce Brooks All rights reserved. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee-Poul Andersen, Helen Baroni, and Edward Davis-------for their ongoing support and patience in this long distance endeavor. Extra thanks are due to Poul Andersen for his suggestions regarding the history and iconography ofYisheng and Zhenwu, as well as his help with translation. I would also like to thank Faye Riga for helping me navigate the formalities involved in this process. To the members of my new family, Pete and Jane Dahlin, lowe my most sincere gratitude. Without their help and hospitality, this project would have never seen the light of day. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my wife Nicole and son Eden for putting up with my prolonged schedule, and for inspiring me everyday to do my best. iv Abstract Images of the Four Saints, a group ofDaoist deities popular in the Song period, survive in a Buddhist context and display elements of Buddhist iconography.