Microbial Metabolite Urolithin B Inhibits Recombinant Human Monoamine Oxidase a Enzyme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Vitro Bioaccessibility, Human Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Hepatoprotective Potential of Chebulic Ellagitannins: a Case of Padma Hepatenr Formulation

Article In Vitro Bioaccessibility, Human Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Hepatoprotective Potential of Chebulic Ellagitannins: A Case of Padma Hepatenr Formulation Daniil N. Olennikov 1,*, Nina I. Kashchenko 1,: and Nadezhda K. Chirikova 2,: Received: 28 August 2015 ; Accepted: 30 September 2015 ; Published: 13 October 2015 1 Laboratory of Medical and Biological Research, Institute of General and Experimental Biology, Siberian Division, Russian Academy of Science, Sakh’yanovoy Street 6, Ulan-Ude 670-047, Russia; [email protected] 2 Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, North-Eastern Federal University, 58 Belinsky Street, Yakutsk 677-027, Russian; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-9021-600-627; Fax: +7-3012-434-243 : These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Chebulic ellagitannins (ChET) are plant-derived polyphenols containing chebulic acid subunits, possessing a wide spectrum of biological activities that might contribute to health benefits in humans. The herbal formulation Padma Hepaten containing ChETs as the main phenolics, is used as a hepatoprotective remedy. In the present study, an in vitro dynamic model simulating gastrointestinal digestion, including dialysability, was applied to estimate the bioaccessibility of the main phenolics of Padma Hepaten. Results indicated that phenolic release was mainly achieved during the gastric phase (recovery 59.38%–97.04%), with a slight further release during intestinal digestion. Dialysis experiments showed that dialysable phenolics were 64.11% and 22.93%–26.05% of their native concentrations, respectively, for gallic acid/simple gallate esters and ellagitanins/ellagic acid, in contrast to 20.67% and 28.37%–55.35% for the same groups in the non-dialyzed part of the intestinal media. -

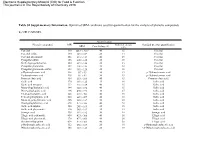

Table 2 of Supporting Information

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Food & Function. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2016 Table S1 Supplementary Information. Optimized SRM conditions used for quantification for the analysis of phenolic compounds by UPLC-MS/MS. Quantification Phenolic compound MW Collision energy Standard used for quantification SRM Cone voltage (v) (eV) Catechol 110 108.9 90.9 40 15 Catechol Catechol sulfate 190 189 109 20 15 Catechol Catechol glucuronide 286 285 123 40 15 Catechol Pyrogallol sulfate 206 205 125 20 15 Catechol Methyl pyrogallol sulfate 220 219 124 20 25 Catechol Pyrogallol glucuronide 302 301 125 20 10 Catechol Pyrogallol glucuronide-sulfate 382 381 125 20 10 Catechol p-Hydroxybenzoic acid 138 137 93 30 15 p-Hydroxybenzoic acid Hydroxybenzoic acid 138 137 93 30 15 p-Hydroxybenzoic acid Protocatechuic acid 154 153 109 40 15 Protocatechuic acid Gallic acid 170 169 125 35 10 Gallic acid Gallic acid hexoside 332 331 169 40 15 Gallic acid Mono-O-galloylquinic acid 344 343 191 40 15 Gallic acid Di-O-galloylquinic acid 496 495 191 40 25 Gallic acid Tri-O-galloylquinic acid 648 647 495 40 15 Gallic acid Tetra-O-galloylquinic acid 630 629 477 40 15 Gallic acid Mono-O-galloylshikimic acid 326 325 169 40 20 Gallic acid Di-O-galloylshikimic acid 478 477 325 40 20 Gallic acid Gallic acid sulphate 250 249 169 35 15 Gallic acid Gallic acid glucuronide 346 345 169 35 15 Gallic acid Syringic acid 198 197 182 30 10 Syringic acid Ellagic acid arabinoside 434 433 300 40 30 Ellagic acid Ellagic acid glucuronide -

Concentrations of Blood Serum and Urinal Ellagitannin Metabolites Depend Largely on the Post-Intake Time and Duration of Strawberry Phenolics Ingestion in Rats

Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci., 2019, Vol. 69, No. 4, pp. 379–386 DOI: 10.31883/pjfns/111866 http://journal.pan.olsztyn.pl Original article Section: Nutritional Research Concentrations of Blood Serum and Urinal Ellagitannin Metabolites Depend Largely on the Post-Intake Time and Duration of Strawberry Phenolics Ingestion in Rats Ewa Żary-Sikorska1*, Monika Kosmala2, Joanna Milala2, Bartosz Fotschki3, Katarzyna Ognik4, Jerzy Juśkiewicz3 1Department of Microbiology and Food Technology, Faculty of Agriculture and Biotechnology University of Science and Technology, Kaliskiego 7, 85–796 Bydgoszcz, Poland 2Institute of Food Technology and Analysis, Łódź University of Technology, Stefanowskiego 4/10, 90–924 Łódź, Poland 3Department of Biological Functions of Food, Institute of Animal Reproduction and Food Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Tuwima 10, 10–748 Olsztyn, Poland 4Department of Biochemistry and Toxicology, Faculty of Biology, Animal Sciences and Bioeconomy, University of Life Sciences, Akademicka 13, 20–950 Lublin, Poland Key words: strawberry, ellagitannins, metabolites, urine, serum, rat The different duration of a strawberry phenolic fraction intake and different post-intake time were experimental factors affecting the concentrations of ellagitannin metabolites in the urine and blood serum of rats. For four days, the animals were gavaged once a day as follows: group C (water, days 1–4), group F1–4 (fraction, days 1–4), group F1–3 (fraction, days 1–3; water, day 4), group F1–2 (fraction, days 1, 2; water, days 3, 4), group F3–4 (water, days 1, 2; fraction, days 3, 4), and group F4 (water, days 1–3; and fraction, day 4). The daily dosage of the fraction gavaged to one rat was 20 mg/kg of body weight. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Kim Ohanna

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO KIM OHANNA PIMENTA INADA EFFECT OF TECHNOLOGICAL PROCESSES ON PHENOLIC COMPOUNDS CONTENTS OF JABUTICABA (MYRCIARIA JABOTICABA) PEEL AND SEED AND INVESTIGATION OF THEIR ELLAGITANNINS METABOLISM IN HUMANS. RIO DE JANEIRO 2018 Kim Ohanna Pimenta Inada EFFECT OF TECHNOLOGICAL PROCESSES ON PHENOLIC COMPOUNDS CONTENTS OF JABUTICABA (MYRCIARIA JABOTICABA) PEEL AND SEED AND INVESTIGATION OF THEIR ELLAGITANNINS METABOLISM IN HUMANS. Tese de Doutorado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências de Alimentos, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências de Alimentos Orientadores: Profa. Dra. Mariana Costa Monteiro Prof. Dr. Daniel Perrone Moreira RIO DE JANEIRO 2018 DEDICATION À minha família e às pessoas maravilhosas que apareceram na minha vida. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Primeiramente, gostaria de agradecer a Deus por ter me dado forças para não desistir e por ter colocado na minha vida “pessoas-anjo”, que me ajudaram e me apoiaram até nos momentos em que eu achava que ia dar tudo errado. Aos meus pais Beth e Miti. Eles não mediram esforços para que eu pudesse receber uma boa educação e para que eu fosse feliz. Logo no início da graduação, a situação financeira ficou bem apertada, mas eles continuaram fazendo de tudo para me ajudar. Foram milhares de favores prestados, marmitas e caronas. Meu pai diz que fez anos de curso de inglês e espanhol, porque passou anos acordando cedo no sábado só para me levar no curso que eu fazia no Fundão. Tinha dia que eu saía do curso morta de fome e quando eu entrava no carro, tinha uma marmita com almoço, com direito até a garrafa de suco. -

Ellagitannin–Lipid Interaction by HR-MAS NMR Spectroscopy

molecules Article Ellagitannin–Lipid Interaction by HR-MAS NMR Spectroscopy Valtteri Virtanen * , Susanna Räikkönen, Elina Puljula and Maarit Karonen Natural Chemistry Research Group, Department of Chemistry, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland; [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (E.P.); maarit.karonen@utu.fi (M.K.) * Correspondence: vtjvir@utu.fi; Tel.: +358-29-450-3205 Abstract: Ellagitannins have antimicrobial activity, which might be related to their interactions with membrane lipids. We studied the interactions of 12 different ellagitannins and pentagalloylglucose with a lipid extract of Escherichia coli by high-resolution magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. The nuclear Overhauser effect was utilized to measure the cross relaxation rates between ellagitannin and lipid protons. The shifting of lipid signals in 1H NMR spectra of ellagitannin–lipid mixture due to ring current effect was also observed. The ellagitannins that showed interaction with lipids had clear structural similarities. All ellagitannins that had interactions with lipids had glucopy- ranose cores. In addition to the central polyol, the most important structural feature affecting the interaction seemed to be the structural flexibility of the ellagitannin. Even dimeric and trimeric ellagitannins could penetrate to the lipid bilayers if their structures were flexible with free galloyl and hexahydroxydiphenoyl groups. Keywords: E. coli; HR-MAS-NMR; interaction; lipid membrane; tannins; UPLC-DAD-MS Citation: Virtanen, V.; Räikkönen, S.; Puljula, E.; Karonen, M. 1. Introduction Ellagitannin–Lipid Interaction by HR-MAS NMR Spectroscopy. Tannins are a group of specialized plant metabolites, which, when included in the di- Molecules 2021, 26, 373. etary feed of ruminants, have been shown to induce many beneficial effects such as increas- https://doi.org/10.3390/ ing their effective amino acid absorption, lowering their methane production, and acting as molecules26020373 anthelmintics [1–6]. -

Berry Flavonoids and Phenolics: Bioavailability and Evidence of Protective Effects

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (2010), 104, S67–S90 doi:10.1017/S0007114510003958 q The Authors 2010 https://www.cambridge.org/core Berry flavonoids and phenolics: bioavailability and evidence of protective effects Daniele Del Rio1, Gina Borges2 and Alan Crozier2* . IP address: 1Human Nutrition Unit, Department of Public Health, University of Parma, Via Volturno 39, 43100 Parma, Italy 2Plant Products and Human Nutrition Group, School of Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Graham Kerr 170.106.202.8 Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK (Received 25 January 2010 – Accepted 24 February 2010) , on 24 Sep 2021 at 06:36:04 Berries contain vitamin C and are also a rich source of phytochemicals, especially anthocyanins which occur along with other classes of phenolic compounds, including ellagitannins, flavan-3-ols, procyanidins, flavonols and hydroxybenzoate derivatives. This review examines studies with both human subjects and animals on the absorption of these compounds, and their glucuronide, sulphate and methylated metabolites, into the cir- culatory system from the gastrointestinal tract and the evidence for their localisation within the body in organs such as the brain and eyes. The involvement of the colonic microflora in catabolising dietary flavonoids that pass from the small to the large intestine is discussed along with the potential fate and role of the resultant phenolic acids that can be produced in substantial quantities. The in vitro and in vivo bioactivities of these , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at polyphenol metabolites and catabolites are assessed, and the current evidence for their involvement in the protective effects of dietary polyphenols, within the gastrointestinal tract and other parts of the body to which they are transported by the circulatory system, is reviewed. -

Inhibitory Activities of Selected Sudanese Medicinal Plants On

Mohieldin et al. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2017) 17:224 DOI 10.1186/s12906-017-1735-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Inhibitory activities of selected Sudanese medicinal plants on Porphyromonas gingivalis and matrix metalloproteinase-9 and isolation of bioactive compounds from Combretum hartmannianum (Schweinf) bark Ebtihal Abdalla M. Mohieldin1,2, Ali Mahmoud Muddathir3* and Tohru Mitsunaga2 Abstract Background: Periodontal diseases are one of the major health problems and among the most important preventable global infectious diseases. Porphyromonas gingivalis is an anaerobic Gram-negative bacterium which has been strongly implicated in the etiology of periodontitis. Additionally, matrix metalloproteinases-9 (MMP-9) is an important factor contributing to periodontal tissue destruction by a variety of mechanisms. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the selected Sudanese medicinal plants against P. gingivalis bacteria and their inhibitory activities on MMP-9. Methods: Sixty two methanolic and 50% ethanolic extracts from 24 plants species were tested for antibacterial activity against P. gingivalis using microplate dilution assay method to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The inhibitory activity of seven methanol extracts selected from the 62 extracts against MMP-9 was determined by Colorimetric Drug Discovery Kit. In search of bioactive lead compounds, Combretum hartmannianum bark which was found to be within the most active plant extracts was subjected to various chromatographic (medium pressure liquid chromatography, column chromatography on a Sephadex LH-20, preparative high performance liquid chromatography) and spectroscopic methods (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)) to isolate and characterize flavogalonic acid dilactone and terchebulin as bioactive compounds. Results: About 80% of the crude extracts provided a MIC value ≤4 mg/ml against bacteria. -

Generating a Qnoael with Confidence Levels from Disparate Literature

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Pharmacy College of Pharmacy 2018 USING THE QBEST EQUATION TO EVALUATE ELLAGIC ACID SAFETY DATA: GENERATING A QNOAEL WITH CONFIDENCE LEVELS FROM DISPARATE LITERATURE Cynthia Rose Dickerson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3572-9374 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2018.394 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dickerson, Cynthia Rose, "USING THE QBEST EQUATION TO EVALUATE ELLAGIC ACID SAFETY DATA: GENERATING A QNOAEL WITH CONFIDENCE LEVELS FROM DISPARATE LITERATURE" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Pharmacy. 94. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pharmacy_etds/94 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Pharmacy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Pharmacy by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

"Ellagic Acid, an Anticarcinogen in Fruits, Especially in Strawberries: a Review"

FEATURE Ellagic Acid, an Anticarcinogen in Fruits, Especially in Strawberries: A Review John L. Maasl and Gene J. Galletta2 Fruit Laboratory, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, MD 20705 Gary D. Stoner3 Department of Pathology, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, OH 43699 The various roles of ellagic acid as an an- digestibility of natural forms of ellagic acid, Mode of inhibition ticarcinogenic plant phenol, including its in- and the distribution and organ accumulation The inhibition of cancer by ellagic acid hibitory effects on chemically induced cancer, or excretion in animal systems is in progress appears to occur through the following its effect on the body, occurrence in plants at several institutions. Recent interest in el- mechanisms: and biosynthesis, allelopathic properties, ac- lagic acid in plant systems has been largely a. Inhibition of the metabolic activation tivity in regulation of plant hormones, for- for fruit-juice processing and wine industry of carcinogens. For example, ellagic acid in- mation of metal complexes, function as an applications. However, new studies also hibits the conversion of polycyclic aromatic antioxidant, insect growth and feeding in- suggest that ellagic acid participates in plant hydrocarbons [e.g., benzo (a) pyrene, 7,12- hibitor, and inheritance are reviewed and hormone regulatory systems, allelopathic and dimethylbenz (a) anthracene, and 3-methyl- discussed in relation to current and future autopathic effects, insect deterrent princi- cholanthrene], nitroso compounds (e.g., N- research. ples, and insect growth inhibition, all of which nitrosobenzylmethylamine and N -methyl- N- Ellagic acid (C14H6O8) is a naturally oc- indicate the urgent need for further research nitrosourea), and aflatoxin B1 into forms that curring phenolic constituent of many species to understand the roles of ellagic acid in the induce genetic damage (Dixit et al., 1985; from a diversity of flowering plant families. -

The Use of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.) Phenolic Compounds As Potential Natural Prevention Against Ibds

15 The Use of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Phenolic Compounds as Potential Natural Prevention Against IBDs Sylvie Hollebeeck, Yvan Larondelle, Yves-Jacques Schneider and Alexandrine During Institut des Sciences de la Vie, UCLouvain, Louvain-la-Neuve Belgium 1. Introduction Phenolic compounds (PCs) are plant secondary metabolites that are integral part of the “normal” human diet. The daily intake of PCs depends on the diet but is commonly evaluated at ca. 1g/day for people who eat several fruits and vegetables per day (Scalbert & Williamson, 2000). PCs may be interesting to prevent the development of inflammatory diseases, more particularly in the gastrointestinal tract, where their concentration may reach levels of up to several hundred µM (Scalbert & Williamson, 2000). Many studies have indeed reported on anti-inflammatory properties of different PCs (see (Calixto et al., 2004; Rahman et al., 2006; Romier et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2009), for reviews). Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) belongs to the Punicaceae family, which includes only two species. More than 500 cultivars of Punica granatum exist with specific characteristics such as fruit size, exocarp and aril color, etc. Originating from the Middle East, pomegranate is now widely cultivated throughout the world, and also widely consumed. Pomegranate has been used for centuries in the folk medicine of many cultures. As described in the review of Lansky et al. (2007), the bark and the roots are believed to have anthelmintic and vermifuge properties, the fruit peel has been used as a cure for diarrhea, oral aphthae, and as a powerful astringent, the juice as a blood tonic, and the flowers as a cure for diabetes mellitus. -

Isolation of Ellagitannin Monomer and Macrocyclic Dimer from Castanopsis Carlesii Leaves

HETEROCYCLES, Vol. 86, No. 1, 2012 381 HETEROCYCLES, Vol. 86, No. 1, 2012, pp. 381 - 389. © 2012 The Japan Institute of Heterocyclic Chemistry Received, 9th June, 2012, Accepted, 20th July, 2012, Published online, 24th July, 2012 DOI: 10.3987/COM-12-S(N)29 ISOLATION OF ELLAGITANNIN MONOMER AND MACROCYCLIC DIMER FROM CASTANOPSIS CARLESII LEAVES Yong-Lin Huang,a,b Takashi Tanaka,*,a Yosuke Matsuo,a Isao Kouno,a Dian-Peng Li,b and Gen-ichiro Nonakac aGraduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki University, 1-14 Bunkyo-Machi, Nagasaki 852-8521, Japan; [email protected] bGuangxi Key Laboratory of Functional Phytochemicals Research and Utilization, Guangxi Institute of Botany, Guilin 541006, China c Usaien Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd., 1-4-6 Zaimoku, Saga 840-0055, Japan Abstract – In a phytochemical and chemotaxonomical investigation of Castanopsis species (Fagaceae), new monomeric and dimeric ellagitannins, named carlesiins A (1) and B (2), were isolated from fresh leaves of Castanopsis carlesii along with 55 known compounds. Carlesiin A was identified as 1-O-galloyl-4,6-(S)-tergalloyl-β-D-glucose. Carlesiin B is a macrocyclic ellagitannin dimer with a symmetrical structure composed of two tergalloyl and two glucopyranose moieties. Their structures were elucidated based on spectroscopic and chemical evidence. INTRODUCTION The species in the Castanopsis (Fagaceae) genus are evergreen trees that are found in East Asia, sometimes as the dominant species in a forest. These trees are often used as forestry or ornamental trees, and the wood is an important construction material. There are about 120 species in the genus, but the chemical compositions of only a few species have been studied. -

Formulation Strategies to Improve Oral Bioavailability of Ellagic Acid

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 7 April 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202004.0100.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3353; doi:10.3390/app10103353 Review Formulation strategies to improve oral bioavailability of ellagic acid Guendalina Zuccari 1,*, Sara Baldassari 1, Giorgia Ailuno 1, Federica Turrini 1, Silvana Alfei 1, and Gabriele Caviglioli 1 1 Department of Pharmacy, Università di Genova, 16147 Genova, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39 010 3352627 Featured Application: An updated description of pursued approaches for efficiently resolving the low bioavailability issue of ellagic acid. Abstract: Ellagic acid, a polyphenolic compound present in fruits and berries, has recently been object of extensive research for its antioxidant activity, which might be useful for the prevention and treatment of cancer, cardiovascular pathologies, and neurodegenerative disorders. Its protective role justifies numerous attempts to include it in functional food preparations and in dietary supplements not only to limit the unpleasant collateral effects of chemotherapy. However, ellagic acid use as chemopreventive agent has been debated because of its poor bioavailability associated to low solubility, limited permeability, first pass effect, and interindividual variability in gut microbial transformations. To overcome these drawbacks, various strategies for oral administration including solid dispersions, micro-nanoparticles, inclusion complexes, self- emulsifying systems, polymorphs have been proposed. Here, we have listed an updated description of pursued micro/nanotechnological approaches focusing on the fabrication processes and the features of the obtained products, as well as on the positive results yielded by in vitro and in vivo studies in comparison to the raw material.