Denominational and Linguistic Guarantees in the Canadian Constitution: Implications for Quebec Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday, October 1, 1997

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 008 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, October 1, 1997 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the followingaddress: http://www.parl.gc.ca 323 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, October 1, 1997 The House met at 2 p.m. Columbians are crying out for federal leadership and this govern- ment is failing them miserably. _______________ Nowhere is this better displayed than in the Liberals’ misman- Prayers agement of the Pacific salmon dispute over the past four years. The sustainability of the Pacific salmon fishery is at stake and the _______________ minister of fisheries sits on his hands and does nothing except criticize his own citizens. D (1400) Having witnessed the Tory government destroy the Atlantic The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesday we will now sing fishery a few years ago, this government seems intent on doing the O Canada, and we will be led by the hon. member for Souris— same to the Pacific fishery. Moose Mountain. It is a simple case of Liberal, Tory, same old incompetent story. [Editor’s Note: Members sang the national anthem] This government had better wake up to the concerns of British Columbians. A good start would be to resolve the crisis in the _____________________________________________ salmon fishery before it is too late. * * * STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS TOM EDWARDS [English] Ms. Judi Longfield (Whitby—Ajax, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I rise today to recognize the outstanding municipal career of Mr. -

Language Guarantees and the Power to Amend the Canadian Constitution

Language Guarantees and the Power to Amend the Canadian Constitution Armand L. C. de Mestral and William Fraiberg * Introduction An official language may be defined as one ordained by law to be used in the public institutions of a state; more particularly in its legislature and laws, its courts, its public administration and its public schools.1 In Canada, while language rights have historically been an issue of controversy, only a partial provision for official languages as above defined is to be found in the basic constitutional Acts. The British North America Act, in sec. 133,2 gives limited re- cognition to both Engish and French in the courts, laws, and legis- latures of Canada and Quebec. With the possible exception of Quebec, the Provinces would appear to have virtually unlimited freedom to legislate with respect to language in all spheres of public activity within their jurisdiction. English is the "official" language of Mani- toba by statute 3 and is the language of the courts of Ontario.4 While Alberta and Saskatchewan have regu'ated the language of their schools,5 they have not done so with respect to their courts and • Of the Editorial Board, McGill Law Journal; lately third law students. 'The distinction between an official language and that used in private dis- course is clearly drawn by the Belgian Constitution: Art. 23. "The use of the language spoken in Belgium is optional. This matter may be regulated only by law and only for acts of public authority and for judicial proceedings." Peaslee, A. J., Constitutions of Nations, Concord, Rumford Press, 1950, p. -

Yes, Your Tweet Could Be Considered Hate Speech,Ontario's

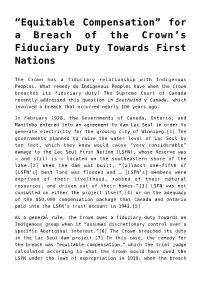

“Equitable Compensation” for a Breach of the Crown’s Fiduciary Duty Towards First Nations The Crown has a fiduciary relationship with Indigenous Peoples. What remedy do Indigenous Peoples have when the Crown breaches its fiduciary duty? The Supreme Court of Canada recently addressed this question in Southwind v Canada, which involved a breach that occurred nearly 100 years ago. In February 1928, the Governments of Canada, Ontario, and Manitoba entered into an agreement to dam Lac Seul in order to generate electricity for the growing city of Winnipeg.[1] The governments planned to raise the water level of Lac Seul by ten feet, which they knew would cause “very considerable” damage to the Lac Seul First Nation (LSFN), whose Reserve was — and still is — located on the southeastern shore of the lake.[2] When the dam was built, “[a]lmost one-fifth of [LSFN’s] best land was flooded and … [LSFN’s] members were deprived of their livelihood, robbed of their natural resources, and driven out of their homes.”[3] LSFN was not consulted on either the project itself,[4] or on the adequacy of the $50,000 compensation package that Canada and Ontario paid into the LSFN’s trust account in 1943.[5] As a general rule, the Crown owes a fiduciary duty towards an Indigenous group when it “assumes discretionary control over a specific Aboriginal interest.”[6] The Crown breached its duty in the Lac Seul dam project.[7] In this case, the remedy for the breach was “equitable compensation,” which the trial judge calculated according to what the Crown would have owed the LSFN under the laws of expropriation in 1929, when the breach occurred.[8] Mr Southwind, who was acting on behalf of the members of the LSFN, disagreed with this calculation and argued that the trial judge failed to consider the doctrine of equitable compensation in light of the constitutional principles of the honour of the Crown and reconciliation.[9] On July 16th, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled on Mr Southwind’s appeal. -

The Other Solitude

THE OTHER SOLITUDE Michel Doucet* It is a fact that New Brunswick’s two official linguistic communities don’t really know much about each other. There are many points of contact between francophones and anglophones in New Brunswick, but the two groups have not really been able to develop a real sense of understanding of each other. This is probably an overly simplistic conclusion to the relationship of the two communities in New Brunswick. Certainly from the Acadian community’s perspective, it is impossible to live in New Brunswick or in Canada and to ignore the presence of the anglophone community. The anglophone community is present in almost eveiy aspect of the francophone community’s daily life: they watch English-language television; they listen to English-language radio; they read the English press every day; they watch English-language movies; there are English expressions on the billboards all over the province, including predominant francophone regions, and English is the language of business and on the streets in many francophone areas of New Brunswick. In some cases, the presence of the English language and culture is so pervasive in the francophone community that it needs to shelter itself from them, a situation which immediately feeds into the misunderstanding between the two communities. Take, for example, the policies of many French-language schools in New Brunswick to ban the use of English during school hours. This is not well understood in the English community, while in the French community, people believe that sometimes it is necessary to adopt such policies in order to protect and preserve the French language. -

A Quebec-Canada Constitutional Law Lexicon (French to English) Wallace Schwab

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:44 a.m. Meta Journal des traducteurs Translators' Journal A Quebec-Canada Constitutional Law Lexicon (French to English) Wallace Schwab Traduction et terminologie juridiques Volume 47, Number 2, June 2002 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/008015ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/008015ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal ISSN 0026-0452 (print) 1492-1421 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Schwab, W. (2002). A Quebec-Canada Constitutional Law Lexicon (French to English). Meta, 47(2), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.7202/008015ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ A Quebec-Canada Constitutional Law Lexicon (French to English) wallace schwab Certified Translator and Terminologist, Ordre des traducteurs, terminologues et interprètes agréés du Québec, Canada INTRODUCTION This past autumn (2001) the Québec government released a landmark French1 pub- lication in the field of constitutional law; the English translation followed shortly thereafter. Québec’s Positions on Constitutional and Intergovernmental Issues2 is an exhaustive cross-referenced compilation encompassing over 60 years of constitu- tional positions (from 1936 to March 2001) taken by the Québec government. -

Mis En Cause's Brief Is in Compliance with the Requirements of the Civil Practice Regulation of the Court of Appeal

500-09-027501-188 COURT OF APPEAL OF QUÉBEC (Montréal) On appeal from a judgment of the Superior Court, District of Montréal, rendered on April 18, 2018 by the Honourable Justice Claude Dallaire. _______ No. 500-05-065031-013 S.C.M. KEITH OWEN HENDERSON APPELLANT (Plaintiff) v. PROCUREUR GÉNÉRAL DU QUÉBEC RESPONDENT (Respondent) - and - ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA MIS EN CAUSE (Mis en cause) - and - SOCIÉTÉ SAINT-JEAN-BAPTISTE DE MONTRÉAL INTERVENER (Intervener) MIS EN CAUSE’S BRIEF Dated February 20, 2019 [g] ~B~FORTUNE Montréal 514 374-0400 Québec 418 641-0101 lafortune.ca - 2 - ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Department of Justice Canada Department of Justice Canada Québec Regional Office Constitutional & Administrative Law East Tower, 9th Floor Section Public Law Sector Guy-Favreau Complex EMB - 3206 200 René-Lévesque Blvd. West 284 Wellington Street Montréal, Québec Ottawa, Ontario H2Z 1X4 K1A 0H8 Per: Me Ian Demers Per: Me Warren J. Newman, Ad. E. Me Claude Joyal, Ad. E. Tel.: 514 496-9232 Tel.: 613 952-8091 Fax: 514 283-8427 Fax: 613 941-1937 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lawyers for the Mis en cause Me Charles O’Brien Me Stephen A. Scott 1233 Island Street Suite 720 Montréal, Québec 4060 Sainte-Catherine Street West H3K 2N2 Westmount, Québec H3Z 2Z3 Tel.: 514 484-0045 Tel.: 514 807-8214 Fax: 514 484-1539 Fax: 514 807-7171 [email protected] [email protected] Lawyers for the Appellant - 3 - Me Jean-Yves Bernard, Ad. -

Constitution of Canada Pdf Download

Constitution of canada pdf download Continue Part of the series on the Constitution of Canada Constitutional History Bill of Rights (1689) Settlement Act (1701) Treaty of Paris (1763) Royal Proclamation (1763) quebec Act (1774) Constitutional Act (1791) Constitution Act (1840) (1867) Supreme Court (1875) Constitutional Act, Act, Constitutional 1886 British North American Laws (1867-1975) Statute of Westminster (1931) The Throne Act (1937) Letters Patent (1947) Canada Law (1982) Constitution Act (1982) Document List of Amendments Unsuccessful Amendments of the Constitutional Law Constitutional Discussion of the Patriarchy Charter of Rights and Freedoms of Canada Canadian Bill the Canadian Human Rights Act is the highest law in Canada. It sets out Canada's governance system and the civil rights and human rights of those who are Canadian citizens and non-Canadians. Its content is a combination of various codified acts, treaties between the Crown and indigenous peoples (both historical and modern), uncoded traditions and conventions. Canada is one of the oldest constitutional democracies in the world. According to section 52 (2) of the Constitution Act 1982, the Constitution of Canada consists of the Canadian Act 1982 (which includes the Constitutional Act of 1982), the acts and orders mentioned in its schedule (including, among other things, the Constitution Act of 1867, formerly the British North America Act, 1867), and any amendments to these documents. The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that the list is not exhaustive, and also includes a number of acts, preliminary confederations and unwritten components as well. Read more about this in the list of Canadian constitutional documents. -

The Québec National Assembly

The Québec National Assembly Magali Paquin The legislature of Québec is one of the oldest in Canada. Although it exhibits the main characteristics of a British-style legislature, its history is marked by the cleavage between anglophones and francophones and the affirmation of the Québécois identity. This unique background sets the Québec National Assembly apart from the other provincial legislatures and is reflected in its institutional framework, party dynamics and members. This paper is an overview of the principal features of the Québec National Assembly including its history, procedures and membership. 2012 CanLIIDocs 320 he history of the Québec legislature1 begins with its legislature. The new legislature was still bicameral, the Constitutional Act of 1791, which divided the with the elected Legislative Assembly in which each TBritish colony into two provinces and gave each former province was equally represented (despite an elected legislature. The legislatures of Upper and the fact that Lower Canada’s population was greater Lower Canada were structured like Westminster and than Upper Canada’s) and the Legislative Council, saw their share of conflict and experimentation. The an upper house whose members were selected by the system in Lower Canada was composed of the elected governor. The governor headed the Executive Council Legislative Assembly, the Legislative Council and a and appointed its members as well. Tensions along governor responsible for the executive function. The linguistic lines remained high. At first banned from latter was assisted by the Executive Council, whose official documents, French became acceptable again members were chosen by London. The system was in the face of political pressure in 1847. -

Quebec Bill 96 — Time for a Primer on Amending the Constitution Ian Peach*

1 Quebec Bill 96 — Time For a Primer on Amending the Constitution Ian Peach* On May 13, 2021, the Government of Quebec introduced Bill 96, “An Act Respecting French, the Official and Common Language of Quebec” in the Quebec National Assembly.1 Bill 96 is a multi-faceted, and fairly sweeping, modernization of the Charter of the French Language, com- monly known as Bill 101. It is primarily an attempt to use the power of the state to ensure that French is used more in Quebec, that more Quebecers are educated in French, and that anyone who wants to learn French has access to French lessons.2 As there is some evidence that French is being used less in Quebec than it has been in recent decades, the government wants to act to make French the “common language of Quebec,” as the Bill’s title suggests. While a num- ber of the provisions of Bill 96 may violate the rights of the English-language minority in the province, which is a matter that should be of concern to all Canadians and the Government of Canada, I want to address another issue with the constitutionality of Bill 96. Near the end of the Bill is one section that is important for its mere existence, even if its content is largely symbolic. Section 159 of the Bill would amend the Constitution of Canada to declare that Quebecers form a nation and that French is the only official language, and the common language, of that nation. Specifically, section 159 says: TheConstitution Act, 1867 (30 & 31 Victoria, c. -

Quebec's View of Rights in a Multinational Federation

UNNERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL REFLECTIONS ON CONFLICTING CONCEPTIONS OF RIGHTS AND THE ENTRENCHMENT OF THE CHARTER OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS IN CANADA QUEBEC'S VIEW OF RIGHTS IN A MULTINATIONAL FEDERATION. THE SIS PRESENTED AS PARTIAL REQUIREMENT OF THE MASTERS OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BY T AKAHITO ARAKI JULY2013 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques · Avertlssement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dana te• respect dea droits de son auteur, qui a signé la formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles :;upérleurs (SDU-522- Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que <<conformément à l' article 11 du Règlement no 8 dea études de cycles supérieure, [l'auteur] concède à l' Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de . publication ~a la totalité ou d'une partie Importante de [son) travail de recherche pour dea fins pédagogiques et non commerclalea. Plus précisément, [l'auteur) autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre dea copies de. [son) travail de recherche à dea ftna non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entrainent pas une renonciation de [la) part [de l'auteur) à [sea) droits moraux ni à [sea) droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf ententé contraire, [l'auteur) conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.~t UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL RÉFLEXIONS SUR LE CONFLIT DES CONCEPTIONS DES DROITS ET L'ENCHÂSSEMENT DE LA CHARTE CANADIENNE DES DROITS ET LIBERTÉS DANS LA CONSTITUTION CANADIENNE. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Constitutional Review in Hong Kong under the `One Country, Two Systems' Framework: An Inquiry into its Establishment, Justication and Scope LI, GUANGXIANG How to cite: LI, GUANGXIANG (2013) Constitutional Review in Hong Kong under the `One Country, Two Systems' Framework: An Inquiry into its Establishment, Justication and Scope, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6966/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Constitutional Review in Hong Kong under the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ Framework: An Inquiry into its Establishment, Justification and Scope Guangxiang Li A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Durham Law School Durham University April 2013 Constitutional Review in Hong Kong under the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ Framework: An Inquiry into its Establishment, Justification and Scope Guangxiang Li Abstract This thesis enquires into the establishment, justification and scope of constitutional review in Hong Kong against the unique constitutional order of ‘One Country, Two Systems’ established in Hong Kong after its return to China in 1997. -

N I. General Principles of Colonial Constitutiondl Law 4

VTOL. XXVI April N 4 THE EARLY PROVINCIAL CONSTITUTIONS J. E. READ The Hague I. General Principles of Colonial Constitutiondl Law The early provincial constitutions were established during the colonial regime, when the British Empire was a unitary state. It was recognized that the new settlements could not be governed effectively from Westminster and that a measure of local repre- sentative government was needed. At the same time there was no room for rival sovereignty. The colonial government had to be limited to local matters and be subordinate to the central government and parliament. There were two types of colonial constitution, prerogative and statutory. No doubt ever existed about the competence of Parliament to provide a constitution for a colony; but there was, at first, serious doubt as to the -extent of the authority of the Crown. The question arose for the first time in the case of Campbell v. Hall I after the surrender of Granada by France to Britain in 1763. After the Proclamation of October 7th, 1763, which author ized the summoning of a representative legislative assembly, and after the appointment of the governor but before he summoned an assembly, the Crown imposed a 4y2% export duty on sugar, thus placing Granada on the same - basis as the other British Leeward Islands. The action was brought by Campbell, a British planter, to recover duties paid, upon the ground that the export duty was_ illegal. Two contentions were put forward : first, that the Crown could not make laws for a conquered country ; and, second, that, before the duty was imposed, the Crown had divested itself of authority to legislate for the colony.