Etd Nct4.Pdf (555Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of the American Knowledge Economy*

The Politics of the American Knowledge Economy* Nicholas Short Harvard University [email protected] August 07, 2020 Abstract The American knowledge economy (AKE) is not a mysterious transition in the organization of economic production. It is instead a politically generated consensus for producing economic prosperity in which intellectual property, and the businesses that produce it, play a leading role. The history of AKE development reveals as much and also shows that, while the legal regimes governing the AKE achieved bipartisan consensus, the AKE would not have emerged without a fundamental realignment within the Democratic Party. The history also shows that the AKE has severe distributional consequences and recent empirical work reinforces the view that the AKE is an engine of geographic, economic, and political inequality. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Characterizing Knowledge Economies 3 3 The Post-War Consensus and the American Knowledge Society 6 4 Three Geographies for American Knowledge Economy Development 10 4.1 The global knowledge economy . 11 4.2 The national industrial innovation debate . 15 4.3 The entrepreneurial states . 20 5 The American Knowledge Economy as an Engine of Inequality 23 5.1 Geographic inequality . 24 5.2 Economic inequality . 27 5.3 Political inequality . 30 6 Conclusion 31 *Thanks will go here. 1 1 Introduction For more than forty years, scholars have explored the idea first articulated by Bell (1974) and others that, starting in the 1970s, the United States transitioned from a Fordist economy rooted -

When God Collides with Race and Class: Working-Class America’S Shift to Conservatism

WHEN GOD COLLIDES WITH RACE AND CLASS: WORKING-CLASS AMERICA’S SHIFT TO CONSERVATISM Mark R. Thompson* The Knights of Columbus are . defending the values of faith and family that bind us as a nation. I appreciate your working to protect the Pledge of Allegiance, to keep us “one nation under God.” I want to thank you—I want to thank you for the defense of the traditional family. [The Family] is a most fundamental institution for our society. I appreciate the fact you’re promoting the culture of life. We’re making progress here in America. Last November, I signed a law to end the brutal practice of partial-birth abortion. This law is constitutional; this law is compassionate; this law is urgently needed; and my administration will vigorously defend it in the courts. We’ll work together to strengthen incentives for adoption and parental notification laws. My 2005 budget [sic], I proposed to more than triple federal funds for abstinence programs in schools and community-based programs above 2001 levels. I’ll continue to work with Congress to pass a comprehensive and effective ban on human cloning. Human life is a creation of God, not a commodity to be exploited by man. I look forward to . defend[ing] the sacred bond of marriage. A few activist judges have taken it upon themselves to redefine the institution of marriage by court order. I support a constitutional amendment to protect the sanctity of marriage by ensuring it is always recognized as the union of a man and woman as husband and wife. -

Lily Geismer History Department * Claremont Mckenna College * 850 Columbia Avenue * Claremont California, 91711 *[email protected]

Lily Geismer History Department * Claremont McKenna College * 850 Columbia Avenue * Claremont California, 91711 *[email protected] Academic Appointments Assistant Professor of United States History, Claremont McKenna College, 2010- Education Ph.D. History, University of Michigan, 2010 Dissertation: “Don’t Blame Us: Grassroots Liberalism in Massachusetts, 1960-1990” Dissertation Committee: Matthew Lassiter (Chair, History), Matthew Countryman (History), Regina Morantz-Sanchez (History), Anthony Chen (Sociology) B.A. History, Brown University, magna cum laude, honors in history, 2003 Publications Books: Don’t Blame Us: Suburban Liberals and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, Princeton University Press, 2015 Journal Articles: “Good Neighbors for Fair Housing: Suburban Liberalism and Racial Inequality in Metropolitan Boston,” Journal of Urban History (May 2013 vol. 39 no. 3): 454-477 “At Home in America through the Lens of Metropolitan and Political History,” Special Issue of the Journal of American Jewish History (forthcoming, 2016) Book Chapters: “Kennedy and the Liberal Consensus” in A Companion to John F. Kennedy, ed. Marc Silverstone, Wiley- Blackwell , 2014 “More Than Megachurches: Liberal Religion and Politics in the Suburbs” in Faithful Republic: Religion and Politics in the 20th Century United States, ed. Andrew Preston, Bruce Schulman, and Julian Zelizer, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015 “‘Ending Welfare as We Know It’: Bill Clinton’s Welfare Reform” in Retrieving the American Past, Pearson (forthcoming, 2016) “Urban Politics Since 1940” in The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, Oxford University Press, (forthcoming, 2016) Other Articles: “Overcoming the Gender and Political History Divide: Teaching and Studying Post-1945 United States History,” with Tamar Carroll Perspectives on History: The Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association (March 2012): 28-30. -

To Download the PDF File

http://www.thenation.com/doc.mhtml?i=20041206&s=nichols The Nation Democrats Score in the Rockies by JOHN NICHOLS [from the December 6, 2004 issue] Imagine a parallel universe where, instead of crying in their beer as the election results rolled in on November 2, Democrats were raising microbrews in toasts to their unprecedented success. Now, stop imagining and focus on the Rocky Mountain West, a region that trended so Republican in the 1990s that a popular joke suggested gays and lesbians were afraid to come out of the closet for fear of being thought to be Democrats. This year the Democrats got the last laugh. While those so-simplistic-as-to-be-useless maps of partisan breakdowns in the presidential race paint the region as hopelessly Republican--feeding the sense that wide expanses of America are lost forever to the Democratic Party--Dan Petegorsky of the Western States Center invites a closer look, which reveals that "the 'red' label on the presidential map contrasts sharply with the state-level results." On the same day that George W. Bush was winning nationally and Republicans were increasing their majorities in Congress, Democrats in the eight states of the Rocky Mountain West were winning state and local contests at a rate not seen in decades and offering valuable lessons for the national Democratic Party, organized labor and progressive activist groups that are sorely in need of new models for campaigning. "Before the pundits write this off as the year when nothing seemed to work right for the Democrats," says Montana Democratic Party executive director Brad Martin, "there is a Western story that needs to be told." Actually, there are several stories. -

How to Win a Fight with a Liberal

✭✮✭✮✭✮✭✮ How to Win a Fight with a Liberal by Daniel Kurtzman Copyright © 2007 by Daniel Kurtzman Cover and internal illustrations by Katie Olsen Cover and internal design © 2007 by Sourcebooks, Inc. Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc. Published by Sourcebooks Hysteria, an imprint of Sourcebooks Inc. P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410 (630) 961-3900 Fax: (630) 961-2168 www.sourcebooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kurtzman, Daniel. How to win a fight with a liberal / by Daniel Kurtzman. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0879-9 (trade pbk.) ISBN-10: 1-4022-0879-0 (trade pbk.) 1. Liberalism--United States--Humor. I. Title. PN6231.L47K87 2007 320.51'30973--dc22 2007010962 Printed and bound in Canada WC 10 9 8 7 6 5 ( Dedication FOR MY WIFE, LAURA, AND FOR MY PARENTS, KEN AND CARYL, AND MY BROTHER,TODD Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: What It Means to Be a Conservative 7 What Breed of Conservative Are You? 9 The Conservative Manifesto 15 Rate Your Partisan Intensity Quotient (PIQ) 17 What’s Your State of Embattlement? 20 Chapter 2: Know Your Enemy 25 The Liberal Manifesto 26 A Field Guide to the Liberal Genus 28 How to Rate a Liberal’s Partisan Intensity Quotient (PIQ) 34 Frequently Asked Questions about Liberals 37 A Glimpse into the Liberal Utopia 40 Chapter 3: Can’t We All Just Get Along? 43 A Day in the Life of Conservatives vs. -

Political Appetites: Food As Rhetoric in American Politics

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Political Appetites: Food as Rhetoric in American Politics Alison Perelman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Perelman, Alison, "Political Appetites: Food as Rhetoric in American Politics" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 907. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/907 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/907 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Appetites: Food as Rhetoric in American Politics Abstract Food is mobilized as a site of political communication. The framing of food as politically relevant is possible because food is deeply rooted in a particular cultural context; because food is symbolic of its culinary community, therefore, it can be deployed as a form of strategic messaging. For that reason food has played a role in political campaigning since the earliest American elections. However major changes to the conditions under which politics is undertaken have altered the messages sent through food. Specifically, the emergence of image-based campaigning and a taste-based notion of elitism has created an environment in which food politics is designed to demonstrate a political figure's connection to, or disconnection from, middle class American culture. This qualitative study investigates three sites--diner politics, food faux pas, and the regulation of food--where food and politics intersect. Data for this analysis consists of textual analysis of over 400 articles published in newspapers and magazines; semi-structured interviews with public health advocates, political officials, and strategists; and candidate speeches and peripheral campaign materials. -

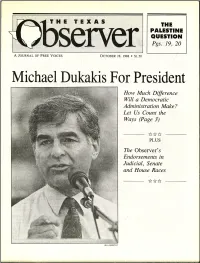

Michael Dukakis for President How Much Difference Will a Democratic Administration Make? Let Us Count the Ways (Page 3)

THE PALESTINE QUESTION Pgs. 19, 20 A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES OCTOBER 28, 1988 • $L50 Michael Dukakis For President How Much Difference Will a Democratic Administration Make? Let Us Count the Ways (Page 3) PLUS The Observer's Endorsements in Judicial, Senate and House Races *** BILL ALBRECHT -,..•- FOE . — •,' -;.:,, _. _. tii,■?.—.. -T..i VI" - - 44:10, DIALOGUE —41 u e t.• i911- '1j 1-7111 - Remembering according to the unabridged 2nd edition of , THE TEXAS Fr dib Mrs. Rosengren Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language (1959). 1 411 server Thank you and Geoffrey Rips for the tribute Of more importance is the fact that a gross to Florence Rosengren (TO, 9/16/88). The injustice, to put it mildly, is being done to A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES world may never be the way Rosengren's a relatively defenseless people, the We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to Bookstore was, but the existence of such Palestinians, with the financial backing the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We a place "radiating understanding, order, and coming from each U.S. taxpayer. (I are dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of humankind as the ferment all at the same time" was one of volunteered for the Army in World War II, foundation of democracy; we will take orders from the signs of hope that the world might serving in North Africa and Europe, because none but our own conscience, and never will we over- become so. -

THE LONG WAR of JOHN KERRY by JOE KLEIN Can a Massachusetts Brahmin Become President?

The New Yorker THE LONG WAR OF JOHN KERRY by JOE KLEIN Can a Massachusetts Brahmin become President? Posted 11-25-2002 On a rainy October morning, the day after Senator John Forbes Kerry, of Massachusetts, an- nounced that he would reluctantly vote to give President George W. Bush the authority to use lethal force against Iraq, the Senator sat in his Capitol Hill office reminiscing about another war and another speech. The war was Vietnam. The speech was one he had delivered upon graduating from Yale, in 1966. Kerry was twenty-two at the time; he had already enlisted in the Navy. As one of Yale’s champion debaters and president of the Political Union, he had been selected to deliver the Class Oration, traditionally an Ivy-draped nostalgia piece. But the speech he gave, hastily rewritten at the last moment, was anything but traditional: it was a broad, passionate criticism of American foreign policy, including the war that he would soon be fighting. I’d been trying to get a copy of this speech for several weeks, but Kerry’s staff had been un- able to find one. There seemed a parallel—at least, a convenient journalistic analogy—to his statement the day before about Iraq: two questionable wars, both of which Kerry had decid- ed to support, conditionally, even as he raised serious doubts about their propriety. Kerry bristled at the analogy. He assumed that a familiar accusation was inherent in the com- parison: that he was guilty of speaking boldly but acting politically. And it is true that from his earliest days in public life—a career that seems to have begun in prep school—even John Kerry’s closest friends have teased him about his overactive sense of destiny, his theatrical sense of gravitas, and his initials, which are the same as John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s. -

The Politics of the American Knowledge Economy

The Politics of the American Knowledge Economy Nicholas Short Harvard University [email protected] 510-206-0397 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2401-8315 April 20, 2021 Abstract The American knowledge economy (AKE) is not a foreordained transition in the organization of economic production nor is it a form of political economy shaped predominately by the political demands of highly educated workers. It is a politically generated consensus for producing economic prosperity and economic advantage over other nations in which intellectual property (IP), and the businesses that produce it, play a leading role. The history of AKE development reveals as much. In the AKE’s formative period, from 1980 to 1994, IP producers and a faction of neoliberal Democrats (the Atari Democrats), not decisive middle class voters, played a pivotal role in recongifuring institutions of American political economy to hasten the AKE transition. Their vision of AKE development inherently complicated the Democratic Party’s attitude towards rising market power and continues to shape contemporary disputes within the Party over antitrust enforcement and the validity of the AKE project itself. Short title: "The Politics of the AKE" Competing interests: The author declares none 1 1 Introduction Though many scholars now accept that, at some point in the last forty years, the United States tran- sitioned from a Fordist economy rooted in mass production to a post-Fordist “knowledge economy,” there is surprisingly little consensus about how we should define or characterize the knowledge -

[email protected]

Curriculum Vitae Elaine Ciulla Kamarck, PhD. The Brookings Institution 1755 Massachusetts Ave. NW Washington, D.C. 20036 202-238-3575 [email protected] Employment January 2013 to present: Senior Fellow and Director of the Brookings Center on Management and Leadership Dr. Kamarck leads a new center devoted to research on public sector management, leadership, institutional innovation and comparative governance. 1997-2012 Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University, Lecturer in Public Policy Dr. Kamarck is on leave from Harvard where she taught courses on Innovation in Government, Strategic Management, American Politics and Public Policy and Contemporary Issues in American Elections. She conducted research on American politics and government innovation. She is the author of The End of Government… As We Know it, a book about the contours of the post-bureaucratic state and the author of Primary Politics: How Presidential Candidates Have Shaped the Modern Nominating System, a book that covers forty years of the evolution of the American political system. She is currently finishing, How Change Happens: Understanding Success and Failure in American Politics, a book that describes the intersection of policy and politics. (Forthcoming). She has served Faculty Chair to four Kennedy School Executive Education Programs: The Ukraine Presidential Cadre Reserve Program; The North Africa Emerging Leaders Program; the Emerging Leaders Program for the Crown Prince Court of Abu Dhabi and a new global open enrollment program called simply Emerging Leaders. And she is a regular lecturer in the Senior Executives in the Federal Government Executive education session for members of the American civil service. During her time at the Kennedy School Dr. -

Elaine Kamarck's CV

Curriculum Vitae Elaine Ciulla Kamarck, PhD. The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave. NW Washington, DC 20036 Employment January 2013 - Present Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Brookings Center for Effective Public Management Dr. Kamarck leads a new center devoted to research on public sector management, leadership, institutional innovation and American politics. Faculty Chair: Emerging Leaders Executive Education Program, Harvard Kennedy School. Dr. Kamarck leads a program on governance, economic development and information and society. This is a highly popular and global course that attracts people from around the world. 1997 - 2012: Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University, Lecturer in Public Policy Dr. Kamarck taught courses on Innovation in Government, Strategic Management, American Politics and Public Policy and Contemporary Issues in American Elections. She conducted research on American politics and government innovation. She has also taught and led many Kennedy School Executive Education Programs: The Ukraine Presidential Cadre Reserve Program; The North Africa Emerging Leaders Program; the Emerging Leaders Program for the Crown Prince Court of Abu Dhabi and a new global open enrollment program called simply Emerging Leaders. And she is a regular lecturer in the Senior Executives in the Federal Government Executive education session for members of the American civil service. During her time at the Kennedy School Dr. Kamarck has taken on a variety of leadership roles in projects related to her research and to the goals of the school. She served as Principal Investigator, Strategic Issues for Intelligence Practice in the 21st Century (2003 – 2005). In that capacity she worked with the CIA and the Department of State to create and lead five executive sessions for senior Intelligence Community Analysts on the future of the intelligence community. -

Nixon's Loyalists

NIXON’S LOYALISTS INSIDE THE WAR FOR THE WHITE HOUSE, 1972 A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Frank Kusch © Copyright Frank Kusch, March, 2010. All rights reserved. i PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain or in any commercial venture shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head, the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B3 ii ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to revisit the American presidential election of 1972 via the interpretive lens of Richard Nixon‟s loyal inner circle.