Management of the Coconut Bug in Avocados

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avocado Production in Home Gardens Revised

AVOCADO PRODUCTION IN HOME GARDENS Author: Gary S. Bender, Ph.D. UCCE Farm Advisor Avocados are grown in home Soil Requirements gardens in the coastal zone of A fine sandy loam with good California from San Diego north drainage is necessary for long life to San Luis Obispo. Avocados and good health of the tree. It is (mostly Mexican varieties) can better to have deep soils, but also be grown in the Monterey – well-drained shallow soils are Watsonville region, in the San suitable if irrigation is frequent. Francisco bay area, and in the Clay soils, or shallow soils with “banana-belts” in the San Joaquin impermeable subsoils, should not Valley. Avocados are grown successfully in be planted to avocados. Mulching avocados frost-free inland valleys in San Diego County with a composted greenwaste (predominantly and western Riverside County, but attention chipped wood) is highly beneficial, but should be made to locating the avocado tree manures and mushroom composts are usually on the warmest microclimates on the too high in salts and ammonia and can lead to property. excessive root burn and “tip-burn” in the leaves. Manures should never be added to Climatic Requirements the soil back-fill when planting a tree. The Guatemalan races of avocado (includes varieties such as Nabal and Reed) are more Varieties frost-tender. The Hass variety (a Guatemalan/ The most popular variety in the coastal areas Mexican hybrid which is mostly Guatemalan) is Hass. The peel texture is pebbly, peel is also very frost tender; damage occurs to the color is at ripening, and it has excellent flavor fruit if the winter temperature remains at 30°F and peeling qualities. -

Propagation Experiments with Avocado, Mango, and Papaya

Proceedings of the AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE 1933 30:382-386 Propagation Experiments with Avocado, Mango, and Papaya HAMILTON P. TRAUB and E. C. AUCHTER U. S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C. During the past year several different investigations relative to the propagation of the avocado, mango and papaya have been conducted in Florida. In this preliminary report, the results of a few of the different experiments will be described. Germination media:—Avocado seeds of Gottfried (Mex.) during the summer season, and Shooter (Mex.) during the fall season; and Apple Mango seeds during the summer season, were germinated in 16 media contained in 4 x 18 x 24 cypress flats with drainage provided in the bottom. The eight basic materials and eight mixtures of these, in equal proportions in each case, tested were: 10-mesh charcoal, 6-mesh charcoal, pine sawdust, cypress sawdust, sand, fine sandy loam, carex peat, sphagnum peat, sand plus loam, carex peat plus sand, sphagnum peat plus sand, carex peat plus loam, sand plus coarse charcoal, loam plus coarse charcoal, cypress sawdust plus coarse charcoal, and carex peat plus sand plus coarse charcoal. During the rainy summer season, with relatively high temperature and an excess of moisture without watering, 10-mesh charcoal, and the mixture of carex peat plus sand plus charcoal proved most rapid, but for the drier, cooler fall season, when watering was necessary, the mixture of cypress sawdust plus charcoal was added to the list. During the rainy season the two charcoal media, sphagnum peat, sand plus charcoal, cypress sawdust plus charcoal, and carex peat plus sand plus charcoal gave the highest percentages of germination at the end of 6 to 7 weeks, but during the drier season the first three were displaced by carex peat plus sand, and sphagnum peat plus sand. -

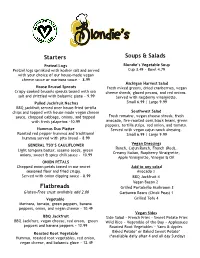

Starters Flatbreads Soups & Salads

Starters Soups & Salads Pretzel Logs Blondie’s Vegetable Soup Pretzel logs sprinkled with kosher salt and served Cup 3.49 ~ Bowl 4.79 with your choice of our house-made vegan cheese sauce or marinara sauce ~ 8.99 Michigan Harvest Salad House Brussel Sprouts Fresh mixed greens, dried cranberries, vegan Crispy cooked brussels sprouts tossed with sea cheese shreds, glazed pecans, and red onions. salt and drizzled with balsamic glaze ~ 9.99 Served with raspberry vinaigrette. Pulled Jackfruit Nachos Small 6.99 | Large 9.99 BBQ jackfruit served over house-fried tortilla chips and topped with house-made vegan cheese Southwest Salad sauce, chopped cabbage, onions, and topped Fresh romaine, vegan cheese shreds, fresh with fresh jalapeños ~10.99 avocado, fire-roasted corn,black beans, green peppers, tortilla strips, red onion, and tomato. Hummus Duo Platter Served with vegan cajun ranch dressing. Roasted red pepper hummus and traditional Small 6.99 | Large 9.99 hummus served with pita bread ~ 8.99 GENERAL TSO’S CAULIFLOWER Vegan Dressings Ranch, Cajun Ranch, French (Red), Light tempura batter, sesame seeds, green Creamy Italian, Raspberry Vinaigrette, onions, sweet & spicy chili sauce – 10.99 Apple Vinaigrette, Vinegar & Oil ONION PETALS Chopped onion petals tossed in our secret Add to any salad seasoned flour and fried crispy. Avocado 2 Served with onion dipping sauce – 8.99 BBQ Jackfruit 4 Vegan Bacon 2 Flatbreads Grilled Portobello Mushroom 3 Gluten-Free crust available add 2.00 Garbanzo Beans (Chick Peas) 1 Vegetable Grilled Tofu 4 Marinara, -

Avocado Production in California Patricia Lazicki, Daniel Geisseler and William R

Avocado Production in California Patricia Lazicki, Daniel Geisseler and William R. Horwath Background Avocados are native to Central America and the West Indies. While the Spanish were familiar with avocados, they did not include them in the mission gardens. The first recorded avocado tree in California was planted in 1856 by Thomas White of San Gabriel. The first commercial orchard was planted in 1908. In 1913 the variety ‘Fuerte’ was introduced. This became the first important commercial variety, due to its good taste and cold tolerance. Despite its short season and Figure 1: Area of bearing avocado trees in California since erratic bearing it remained the industry 1925 [4,5]. standard for several decades [3]. The black- skinned ‘Hass’ avocado was selected from a seedling grown by Robert Hass of La Habra in 1926. ‘Hass’ was a better bearer and had a longer season, but was initially rejected by consumers already familiar with the green-skinned ‘Fuerte’. However, by 1972 ‘Hass’ surpassed ‘Fuerte’ as the dominant variety, and as of 2012 accounted for about 95% of avocados grown in California [3]. By the early 1930s, California had begun to export avocados to Europe. Figure 2: California avocado production (total crop and Research into avocados’ nutritional total value) since 1925 [4,5]. benefits in the 1940s — and a shortage of [1,3] fats and oils created by World War II — in the early 1990s . The state’s crop lost over [5] contributed to an increased acceptance of the half its value between 1990 and 1993 (Fig. 2) . fruit [3]. However, acreage expansion from 1949 Aggressive marketing, combined with acreage to 1965 depressed markets and led to slightly reduction, revived the industry for the next [1,3] decreased plantings through the 1960s (Fig. -

Physico-Chemical, Morphological and Technological Properties of the Avocado (Persea Americana Mill

Ciência e Agrotecnologia, 44:e001420, 2020 Food Science and Technology http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-7054202044001420 eISSN 1981-1829 Physico-chemical, morphological and technological properties of the avocado (Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass) seed starch Propriedades físico-químicas, morfológicas e tecnológicas do amido do caroço de abacate (Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass) Jéssica Franco Freitas Macena1 , Joiciana Cardoso Arruda de Souza1, Geany Peruch Camilloto2 , Renato Souza Cruz2* 1Universidade Federal da Bahia/UFBA, Salvador, BA, Brasil 2Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana/UEFS, Feira de Santana, BA, Brasil *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received in January 17, 2020 and approved in April 14, 2020 ABSTRACT Avocado seeds (Persea americana Mill) are a byproduct of fruit processing and are considered a potential alternative source of starch. Starch is widely used as a functional ingredient in food systems, along with additives such as salt, sugars, acids and fats. This study aimed to perform the physicochemical, morphological and technological characterization of starch from avocado seeds and to evaluate the consistency of gels when salt, sugar, acid and fat are added. Extraction yield was 10.67% and final moisture 15.36%. The apparent amylose content (%) was higher than other cereal and tuber starches. XRD standards confirmed the presence of type B crystallinity, typical of fruits and tubers, with a crystallinity degree of 56.09%. The swelling power increased with increasing temperature (above 70 °C). Avocado seed starch (ASS) presented a syneresis rate of 42.5%. Viscoamylography showed that ASS is stable at high temperatures. TPA analysis showed that ASS gels with different additives and concentrations varied significantly (p<0.05) from the control sample, mainly in the hardness and gumminess profiles. -

Greensheet-March-1-2021.Pdf

Volume 37 Ι Issue 5 Ι March 1, 2021 IN THIS ISSUE, YOU’LL FIND: Nominations for Hass Avocado Board Now Open CAC Releases Updated 2021 Crop Volume and Harvest Projections COVID Vaccines Available for Agricultural Workers in San Diego County New Website Provides Employers with COVID-19 Compliance Assistance How Textural Stratification of Soil Impacts Irrigation Spring Is Ideal For ProGibb LV Plus® Application Point-of-Sale Data Reveals Marketing Program’s Success in Building Demand for Avocados Market Trends Crop Statistics Weather Outlook Calendar For a listing of industry events and dates for the coming year, please visit: http://www.californiaavocadogrowers.com/commission/industry-calendar CAC Finance Committee Web/Teleconference March 4 March 4 Time: 9:00am – 9:55am Location: Web/Teleconference CAC Board Web/Teleconference Meeting March 4 March 4 Time: 10:00am – 12:30pm Location: Web/Teleconference Nominations for Hass Avocado Board Now Open The Hass Avocado Board, comprised of 12 members, is now accepting nominations. HAB plays an important role in promoting consumption of Hass avocados across the United States. HAB board members attend four meetings a year and by sharing their expertise play an important decision-making role concerning HAB policies, research, promotional programs and direction. The term for new members and alternates begins November 1, 2021, with those newly elected being officially seated at the board meeting on December 1, 2021. HAB mailed board nomination announcements to all eligible producers and importers on March 1. The timeline for the remainder of the process is as follows: • March 30 — Deadline for receipt of nomination forms Page 1 of 13 • April 26 — Ballots mailed to producers and importers • May 24 — Deadline for receipt of ballots • June 7 — Nominations results announced by board with two nominees for each position in industry preference provided for consideration to the USDA Secretary of Agriculture Complete information is provided on the HAB website. -

The REAL Food Pyramid Has Been Created As a Meal Planning Guide for Individuals with Eating Disorders

The R.E.A.L. Food Pyramid This information is designed to provide you with a guideline for healthy eating. If you have a special condition or are under medical supervision, you should discuss your eating plan with your doctor. The Recovery from Eating Disorders for Life Food Pyramid The REAL Food Pyramid has been created as a meal planning guide for individuals with eating disorders. It is ideal if it is used in collaboration with a dietitian, as every person is unique, and there may be foods or amounts that need to be adjusted for you. Carbohydrates Choose a variety of whole grains and carbohydrate foods for dietary fibre, thiamine, folate and iodine. Carbohydrate is needed to stabilise your blood glucose level, and provide fuel for your muscles and your brain. Not eating enough carbohydrate can lead to tiredness, fatigue, dizziness, irritability, and low blood glucose levels. It can also precipitate binge eating, particularly at mid-afternoon (around 3-4 pm) when blood glucose levels naturally drop and cravings commonly kick in. Good sources of carbohydrates include: cereals, rice, oats, bread, noodles, potato, quinoa, pasta, cous cous, tortillas. Protein Protein rich foods provide iron, zinc, vitamin B12 and omega-3. Protein is needed for growth and repair of body tissues and plays an important role in all functions of your body. If you are vegetarian, it is important to replace animal proteins with iron -rich substitutes. Good sources of protein include: meat, chicken, fish, eggs, cheese, tofu, chickpeas, lentil, baked beans, ham, nuts, kidney beans. entre for C linical Developed in conjunction with dieticians Susan Hart and Caitlin McMaster C nterventions This document is for information purposes only. -

CINDI Dietary Guide

EUR/00/5018028 EUROPEAN HEALTH21 TARGET 11 HEALTHIER LIVING By the year 2015, people across society should have adopted healthier patterns of living (Adopted by the WHO Regional Committee for Europe at its forty-eighth session, Copenhagen, September 1998) ABSTRACT The WHO Regional Office for Europe is committed to promoting an integrated approach to health promotion and disease prevention. These dietary guidelines provide information that health professionals can relay to their clients to help them prevent disease and promote health. This guide demonstrates that a healthy diet is based mainly on foods of plant origin, rather than animal origin. It also focuses on the need to provide information on the link between health and diet for the most vulnerable groups in society, notably people with low incomes. Just as the quality of air and water is vital, the quantity and quality of food eaten are crucial for human health. A healthy variety of safe food, produced in a sustainable way, is one of the best ways to support a healthy society. Within this context, this document presents twelve steps to healthy eating. Keywords DIET NUTRITION POLICIES NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS EATING GUIDELINES CINDI food pyramid posters are available from: WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8, 2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark ISBN 92 890 1183 1 © World Health Organization – 2000 All rights in this document are reserved by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. The document may nevertheless be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced or translated into any other language (but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes) provided that full acknowledgement is given to the source. -

113 Comparative Study of the Constituents of the Fruits Pulps And

JJC Jordan Journal of Chemistry Vol. 12 No.2, 2017, pp. 113-125 Comparative Study of the Constituents of the Fruits Pulps and Seeds of Canarium ovatum, Persea americana and Dacryodes edulis Omolara O. OLUWANIYI, Friday O. NWOSU and Chinelo M. OKOYE Department of Industrial Chemistry, University of Ilorin, P.M.B 1515, Ilorin, Nigeria Received on May 7, 2017 Accepted on Oct. 2, 2017 Abstract This work was carried out to evaluate and compare the nutritional and phytochemical composition of three pears commonly consumed as food/snacks in Nigeria. The nutritional and phytochemical composition of the pulps and seeds of African pear (Dacryodes edulis), avocado pear (Persea americana) and Pili nut (Canarium ovatum) were determined using standard methods. The amino acid composition of the fruit pulps was also determined using an amino acid analyzer while the fatty acid composition of the oils extracted from the seeds and pulps was determined using GC-MS. The results show that all three species are good sources of food nutrients. Crude fibre (46.33%) and carbohydrate (54.23%) were more abundant in the African pear seed while Pili nut was found to contain the highest level of fat (45.29%). The avocado pear seed had the highest ash (3.50%) and the lowest protein content (1.33%). Tannin was more abundant in the avocado pear seed (0.76mg/100g) and least in the African pear seed (0.24mg/100g); saponin occurred most in avocado pear pulp (0.88mg/100g) and least in avocado pear seed (0.52mg/100g) while phytates were found more in Pili nut (0.58mg/100g). -

California Avocado Varieties: Past, Present and Future (?)

California Avocado Varieties: Past, Present and Future (?) Mary Lu Arpaia, Eric Focht, Rodrigo Iturrieta The UC Riverside team working to develop new varieties and understand avocado genetics Eric Focht Rodrigo Iturrieta Mary Lu Arpaia The past and current challenges do we need additional varieties? Mary Lu Arpaia Botany and Plant Sciences, UCR The industry has been dominated by 2 varieties over the last 100 years Fuerte (1920 – 1970’s) Hass (1970’s – present) Alejandro Le Blanc FUERTE Brought from Atlixco, Mexico in 1911 Popenoe, CAS, 1919 FUERTE • The leading variety from 1920’s to 1970’s • Adapted to a wide variety of climates, especially cold • Known for high fruit quality (Winter-Spring) • Large spreading tree • Recognized to have erratic or severe alternate bearing The rise of Hass It took a long time Facts about Hass . Chance find in La Habra Heights in 1926 and patented in 1935 . High fruit quality when harvested at proper maturity . Considered interesting but black skin considered a flaw as compared to leading variety Fuerte . Did not overtake Fuerte in importance until the planting boom of the mid-1970’s . Now worldwide leading variety and major variety marketed in US Rudolph and Elizabeth Hass Other varieties…. Pinkerton, Reed, Zutano, Bacon, Sharwil etc…. The contributions of B. O. Bergh B. O. Bergh oversaw an active program B.O. Bergh from the 1950’s through 1994. Based on industry input he set out to develop a “green-skinned” Hass. This resulted in the release of ‘Gwen’ in 1984. In a second wave, ~60,000 seedlings, primarily derived from ‘Gwen’, ‘Whitsell’, ‘Hass’ and ‘Pinkerton’, were planted. -

The Aims and Accomplishments of the California Avocado Society

California Avocado Society 1948 Yearbook 33:135-136 The Aims and Accomplishments of the California Avocado Society A.W. Christie (Presented at Annual Meeting, June 5, 1948) When the Directors were arranging the program for this annual meeting, one of them insisted that I make a brief presentation on the aims and accomplishments of the Society. For those who have been members for years, this is hardly necessary, but for those present whose interest in the avocado is quite recent, it may not be amiss. Why I should be on this spot is not clear, unless it be that I have been a director longer than any other member of the board. The director who put me on this spot promised to outline my speech for me, but failed to do so, probably because he recently acquired a new wife. The California Avocado Society was organized in 1915 "to promote the advancement and general welfare of the avocado, and other subtropical fruits, as a horticultural industry." This society is the oldest and most widely known organization concerned with the avocado. While primarily Californian, its membership and recognition are world- wide. In 1947 we had 805 members, of which 44 were in other states of the union, and 54 were in 14 different foreign countries. The international aspect of the Society is illustrated by the pilgrimages in 1938 and again in 1948 to Atlixco, Mexico, the home of the parent Fuerte tree, as well as exploration trips by certain society directors and members to study avocados in their native homes in Mexico and Guatemala. -

The Hass Avocado H

California Avocado Society 1945 Yearbook 30: 27-31 The Hass Avocado H. B. Griswold There is a growing group within the California Avocado industry who believe that the Hass avocado is now our number two variety and that in tonnage it is destined to eventually exceed all other varieties excepting only the Fuerte. This group points out that the Hass season compliments the Fuerte season making possible a two variety coverage of the year as in the orange industry. Its paramount appeal to the grower is its heavy and precocious production. This fact coupled with its excellent eating and shipping quality, long season and medium size make it a profitable fruit for the entire industry. The Fuerte is the only old variety that continues to grow in importance. Of the others only the Nabal and Anaheim have continued to be planted in a limited amount for certain special areas. Many new varieties have been experimented with in the past ten years but of these only the Hass and the MacArthur are now gaining in favor. The Hass is gaining acceptance in a wide area, possibly being suited to all avocado districts. This makes the Hass the "runner up" to the Fuerte for top rating and unless some new yet undeveloped variety makes a spectacular rise the Hass will eventually command the second largest tonnage in the California avocado industry. The parent Hass tree, a Guatemalan seedling, is on the R. G. Hass place at 430 West Road, La Habra Heights. It was one of three hundred sprouted seeds obtained from A.