In Memoriam Dr Edwin Hatch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 30, Number 2 Fall 2019

Volume 30, Number 2 Fall 2019 Are the Canonical Gospels to Be Identified as a Genre of Greco-Roman Biography? The Early Church Fathers Say ‘No.’ F. DAVID FARNELL Job’s Eschatological Hope: The Implications of Job’s Redeemer for Social Justice JAMIE BISSMEYER And How Shall They Hear Without a Preacher? A Biblical Theology of Romans 9–11 GREGORY H. HARRIS A Dynamic Relationship: Christ, the Covenants, and Israel CORY M. MARSH Romans 7: An Old Covenant Struggle Seen through New Covenant Eyes JAY STREET The Reformation’s “Macedonian Call” to Africa—the Long Way Around DAVID BEAKLEY AND JOHANN ODENDAAL Implication and Application in Exposition, Part 2: Principles for Contemporary Application CARL A. HARGROVE TMS.edu Volume 30 Fall 2019 Number 2 The Master’s Seminary Journal CONTENTS Editorial ................................................................................................................. 181-83 Nathan Busenitz Are the Canonical Gospels to Be Identified as a Genre of Greco-Roman Biography? The Early Church Fathers Say ‘No.’ ............................................... 185-206 F.David Farnell Job’s Eschatological Hope: The Implications of Job’s Redeemer for Social Justice .......................................................................................................... 207-26 Jamie Bissmeyer And How Shall They Hear Without a Preacher? A Biblical Theology of Romans 9–11 .................................................................................................... 227-55 Gregory H. Harris A Dynamic Relationship: -

The Economic and Honorific Organization of the Corinthian Ekklēsia

Money, Meals, and Honour: The Economic and Honorific Organization of the Corinthian Ekklēsia By Richard Last A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Last 2013 Abstract Money, Meals, and Honour: The Economic and Honorific Organization of the Corinthian Ekklēsia Richard Last Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto In standard portrayals of Paul’s Corinthian ekklēsia, the Christ-group is said to have existed without the level of economic and honorific organization we know to have been rather generalized in Greco-Roman associations: it did not collect subscription fees, failed to appoint or elect temporary officers, and neglected presentation of formal honorific prizes to its service- providers (e.g., crowns, proclamations, honorific inscriptions). In contrast to ancient associations, the ekklēsia, many scholars presently maintain with very little disagreement, had “no real organization” (Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians, 298), and its members shared a “close, undifferentiated mode of social relationship” (Meeks, First Urban, 88) that is often described as ecclesiastical egalitarianism. This dissertation offers a different perspective by setting the practices of the Corinthian Christ-group alongside practices that are much more fully known from Greco-Roman associations, and asks whether the structural features (economic and honorific) we know to have been common in Greco-Roman associations might also be evidenced in the Corinthian Christ- group. My argument is that the ekklēsia was a structurally sophisticated group equipped with a common fund and a schedule for subscription fees, a “flat hierarchy” of elected temporary officers, and competition among members to perform services that would be reciprocated with crowns and other forms of formal commendation. -

Parish News June 2020

1 Parish News - June 2020 Parish News St Mary the Virgin, Saffron Walden St John, Little Walden and St James, Sewards End Part of Saffron Walden & Villages Team Ministry June 2020 FREE 2 Parish News - June 2020 Welcome to Magdalene Rose! Sam and Rachel Prior are delighted to welcome their daughter Magdalene Rose into their family. Magdalene was born on Monday 27th April 2020 at 11am, weighing 7lb 3oz. All are doing well and are very grateful for all your prayers and good wishes. Rachel and Sam write: - "Thank you all so much for your emails, cards and gifts. We are so touched by your kindness and generosity, and though we may be far apart from you, we feel you are very close. Please do continue to pray for us as we adjust to life as a family of three. We so look forward to the time when you can meet Magdalene face to face! Love, Rachel and Sam 3 Parish News - June 2020 Contents for June 2020 THE PASTORAL LETTER 5 PARISH NEWS - EDITORIAL DEADLINE The deadline for contributions for each issue is st NOTICEBOARD the 1 Sunday of the month. Hence, the dead- Calendar - Major Festivals 7 line for the July issue is Sunday 7th June and for Calling all photographers 17 the August-September issue Sunday 5th July. From the Registers 6 Friends’ visit to Lincoln - update 29 Copy to Parish Administrator: Dawn Saxon REPORTS email: [email protected] Welcome to Magdalene Rose! 2 01799 506024 St Mary’s Music News 28 Editor: Andy Colebrooke FEATURES 01799 732970 Choosing a new Rector for St Mary’s 9 Advertising: Gillian Brace Email: [email protected] -

Theologie Studieren

Albert Raffelt Theologie studieren Albert Raffelt Theologie studieren Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten und Medienkunde Reprofähige Druckvorlage durch den Autor Alle Rechte vorbehalten ± Printed in Germany Verlag Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2003 www.herder.de Umschlaggestaltung: Finken & Bumiller, Stuttgart Druck und Bindung: fgb ´ freiburger graphische betriebe 2003 www.fgb.de Gedruckt auf umweltfreundlichem, chlorfrei gebleichtem Papier ISBN 3-451-28066-3 Inhalt Einleitung ............................. 1 1 Studieren in der Informations- und Mediengesellschaft .. 7 Neue Medien und neue Kommunikationswege 7 ± Der Computer als Hilfsmittel 8 ± Das Medium ist nicht die Botschaft 9 2 Institutionen ........................... 10 Fakultäten und Fachbereiche 10 ± Bibliotheken 11 ± Buch- und Medienhandel, Antiquariatsbuchhandel 14 3 Fachbücher, Fachzeitschriften, neue Medien ± eine Typologie .......................... 17 Enzyklopädien, Lexika 17 ± Fachhandbücher 19 ± Hilfs- bücher 20 ± Textausgaben, Quelleneditionen 21 ± Hoch- schulschriften 24 ± Fachzeitschriften 26 ± Elektronische Publikationen 30 4 Literatursuche .......................... 36 Der Online-Hauptkatalog 36 ± Spezielle Online-Kata- loge 46 ± Traditionelle Kataloge 49 ± Bibliographien und bibliographische Datenbanken 54 ± Allgemeinbiblio- graphie ± Monographien, Zeitschriftentitel 55 ± Sonder- formen bibliographischer Recherche 60 ± Biographische Information, Institutionen, Adressen 61 ± Praxis der Literatursuche 62 ± Internet-Suchmaschinen 65 ± Inter- net-Fachportale 67 5 Literaturangaben, -

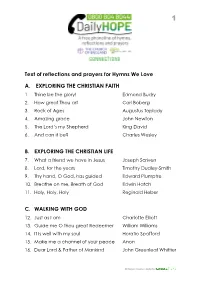

Text of Reflections and Prayers for Hymns We Love

1 Text of reflections and prayers for Hymns We Love A. EXPLORING THE CHRISTIAN FAITH 1. Thine be the glory! Edmond Budry 2. How great Thou art Carl Boberg 3. Rock of Ages Augustus Toplady 4. Amazing grace John Newton 5. The Lord’s my Shepherd King David 6. And can it be? Charles Wesley B. EXPLORING THE CHRISTIAN LIFE 7. What a friend we have in Jesus Joseph Scriven 8. Lord, for the years Timothy Dudley-Smith 9. Thy hand, O God, has guided Edward Plumptre 10. Breathe on me, Breath of God Edwin Hatch 11. Holy, Holy, Holy Reginald Heber C. WALKING WITH GOD 12. Just as I am Charlotte Elliott 13. Guide me O thou great Redeemer William Williams 14. It Is well with my soul Horatio Spafford 15. Make me a channel of your peace Anon 16. Dear Lord & Father of Mankind John Greenleaf Whittier © Steve Cramer 2020 for 2 1. THINE BE THE GLORY! Imagine the scene 2,000 years ago. Early on that first Easter Sunday morning, the followers of Jesus were devastated and hidden away, fearful of what lay ahead. All their hopes for a wonderful future seemed shattered because Jesus, their master and teacher from God, in whom they had put their faith and their hope, whom they had loved and followed, was now dead. Early that morning, the disciples Peter & John were together when suddenly Mary Magdalene arrived shouting that someone had moved Jesus’ body, but she didn’t know where. Peter and John immediately ran to the tomb and there they found the folded grave clothes where the Jesus’ body should have been. -

Ex Nihilo: the Development of the Doctrines of God and Creation in Early Christianity

Ex Nihilo: The Development of the Doctrines of God and Creation in Early Christianity Keith Norman Many men say there is one God: the Son and the Holy Ghost are only one God! I say that is a strange God anyhow—three in one, and one in three! It is a curious organization. “Father, I pray not for the world, but I pray for them which Thou hast given me.” “Holy Father, keep through Thine own name those which Thou hast given me, that they be one as we are.” John 17:9, 11. All are to be crammed into one God, according to sectarianism. It would make the biggest God in all the world. He would be a wonderfully big God—He would be a giant or a monster. .1 Joseph Smith’s caricature of the creedal mire in which orthodox Christianity has been stuck for so long, although apparently based on the sixth-century Athanasian Creed,2 is indicative of the confusion and 1. Joseph Smith, Jr., History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 7. vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1971), 6:476. (Cited hereafter as HC.) 2. The origin of this most orthodox Catholic creed is obscure; it was ascribed to Athanasius after the ninth century, although much closer to Augustine in wording and thought. The first part is as follows: “Whosoever will be saved: before all things it is necessary that he hold the Catholic Faith: Which Faith except everyone do keep whole and undefiled: without doubt he shall perish everlastingly. -

A Biblical and Theological Analysis of Tithing

A BIBLICAL AND THEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF TITHING: TOWARD A THEOLOGY OF GIVING IN THE NEW COVENANT ERA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary Wake Forest, North Carolina In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by David A. Croteau December 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © 2005 David A. Croteau This Dissertation was prepared and presented to the Faculty as a part of the requirements for the Master of Theology degree at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, Wake Forest, North Carolina. All rights and privileges normally reserved by the author as copyright holder are waived for the Seminary. The Seminary Library may catalog, display, and use this Thesis in all normal ways such materials are used, for reference and for other purposes, including electronic and other means of preservation and circulation, including on-line computer access and other means by which library materials are or in the future may be made available to researchers and library users. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A BIBLICAL AND THEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF TITHING: TOWARD A THEOLOGY OF GIVING IN THE NEW COVENANT ERA The members of the Committee approve the doctoral dissertation of David A. Croteau Dr. Andreas Kostenberger Major Professor Dr. David Beck Dr. David Jones Dr. Craig Blomberg Dr. Craig Blomberg Distinguished Professor of New Testament Denver Seminary Dr. Andreas Kostenberger Director ofPh.D.lTh.M. Studies / 7 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

All Saints Church Boyne Hill Maidenhead Parish News

ALL SAINTS CHURCH BOYNE HILL MAIDENHEAD PARISH NEWS www.allsaintsboynehill.org.uk Issue 71 25 August 2021 Dear Parishioners and Friends of All Saints, Boyne Hill, Last Thursday morning a group of people gathered at Stubbings Church to keep a Vigil of prayer for Afghanistan. Fr John Ainslie had invited people to follow the example of Pope Francis in keeping this country and its people in prayer. ‘I join in the unanimous concern for the situation in Afghanistan. I ask all of you to pray with me to the God of peace, so that the clamour of weapons might cease and solutions can be found at the table of dialogue.’ Pope Francis, 15 August during his Angelus address. Fr John offered those of us praying in the church the following suggestions which I thought you may like to use as a focus for prayer this coming week. For the ordinary people of Afghanistan. For those who now live in fear for their lives in Afghanistan for vulnerable groups, especially women and children. For the Taliban Government, that it would seek the common good with compassion and respect for human rights and build a just and compassionate society. For peace and return to normal life in this time of transition. For the helpful and constructive relations between the new regime and the international community. For the rejection of all forces of terrorism in whatever form. For UNICEF and NGO’s working in Afghanistan. For those awaiting evacuation to other countries, especially Afghans who have worked for British Forces; for the military and diplomatic personnel managing the evacuation process. -

Description and Finding Aid JOHN AMBERY COLLECTION F2060

Description and Finding Aid JOHN AMBERY COLLECTION F2060 Prepared by Lynn McIntyre July 2013 John Ambery collection JOHN AMBERY COLLECTION Dates of creation: 1842-1903 Extent: 2 files of textual material Biographical sketch: John Ambery, academic, was born in April 1828 in Manchester, England, and died in 1878 in England. He attended the Manchester Grammar School and Brasenose College, Oxford. Upon graduation, he was appointed Professor of Classics in St. Andrew's College, Bradford, England. In 1856 John Ambery left England and was appointed Lecturer in Classics at Trinity College, Toronto. Two years later he moved to the Toronto Grammar School as classical master. He also held the position of Inspector of Grammar Schools and was a member of the Council of Education. Ambery returned to Trinity in 1863, holding the dual post of Professor of Classics and Dean of Residence until 1875, when he was compelled by ill health to resign. In 1858 he married Henrietta Frederick Foster, youngest daughter of Colonel Colley Lyons Lucas Foster. They had four children: Ellen Marian, Charles Clayton, Edward Foster, and John Willis. In 1876 he was appointed to the Chair of Classics at Bishops College, Lennoxville, Quebec, In 1878 he returned to England. [Source: Biographical sketch of John Ambery by his son, Edward Foster Ambery in F2067, Irving H. Cameron fonds, Trinity College Archives.] Scope and content: The fonds consists of a letter book and an itemized list of the contents of that letter book. A significant portion of the correspondence is in regard to a letter published in The Globe on 2 February 1875. -

Money, Meals, and Honour: the Economic and Honorific Organization of the Corinthian Ekklēsia

Money, Meals, and Honour: The Economic and Honorific Organization of the Corinthian Ekklēsia By Richard Last A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Last 2013 Abstract Money, Meals, and Honour: The Economic and Honorific Organization of the Corinthian Ekklēsia Richard Last Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto In standard portrayals of Paul’s Corinthian ekklēsia, the Christ-group is said to have existed without the level of economic and honorific organization we know to have been rather generalized in Greco-Roman associations: it did not collect subscription fees, failed to appoint or elect temporary officers, and neglected presentation of formal honorific prizes to its service- providers (e.g., crowns, proclamations, honorific inscriptions). In contrast to ancient associations, the ekklēsia, many scholars presently maintain with very little disagreement, had “no real organization” (Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians, 298), and its members shared a “close, undifferentiated mode of social relationship” (Meeks, First Urban, 88) that is often described as ecclesiastical egalitarianism. This dissertation offers a different perspective by setting the practices of the Corinthian Christ-group alongside practices that are much more fully known from Greco-Roman associations, and asks whether the structural features (economic and honorific) we know to have been common in Greco-Roman associations might also be evidenced in the Corinthian Christ- group. My argument is that the ekklēsia was a structurally sophisticated group equipped with a common fund and a schedule for subscription fees, a “flat hierarchy” of elected temporary officers, and competition among members to perform services that would be reciprocated with crowns and other forms of formal commendation. -

2009-220 001 015.Pdf

.. ALGOMA CLERGY PRE DIOCESEAN George Archbold - d. 1823 p. 1824 Que. Asst. Quebec Cathedral 1823; SPG Missionary - Shores of Lake Huron .- 1830 (Coldwater). James Dougall Cameron - son of John Dugald Cameron (1777-1857) Chief Factor in Northwest Company at Whitefish & LaCloche. Mother was an Ojibway. Brother William trained under the Rev'd John West at Norway House and was ordained C of E by Bishop Stewart of Quebec in 1832. Brother Duncan was Provincial Secretary of Upper Canada 1817-1838 and merchant at York. J.D. was lay teacher at Sault Ste. Marie Oct. 1831-Spring 1832. Left Anglicans to become an Anabaptist serving the north shore of Lake Superior. William McMurray (19 Sept. 1810 Portadown, Ire . - 19 May 1894) ed. Trinity College, Toronto. d. 1833 Que. 1840 Toronto. Mission Sault Ste. Marie 1832-1840; Ancaster & Dundas (Niagara) 1840-1856; St. Mark's, Niagara-on-the-Lake 1857; Archdeacon of Niagara 1867. Hon. DCL Trinity College, Toronto. Adam El liot Travelling Missionary for The Society for Converting and Civilizing the Indians of Upper Canada and Propagating the Gospel Among the Destitute Settlers. 1835- First Communion on Ma nitoul in at Manitowaning June 1835 First Communion at Sault Ste. Marie June 1835 • Returned to Manitowaning June 1836 Charles Crosbie Brough (1794-1 873) ed. Trinity College, Dublin. Coldwater 1837-1838; Manitowaning 1838-1840; Archdeacon of London, Huron Diocese. Frederick Augustus O'Meara (7 Jan. 1814 Wexford, Ire. - ed. Trinity College, Dublin 1837 . d 1837 London, Eng. p. 1838 Que. Travelling Missionary Home District 1838- 1839; Sault Ste. Mar1e 1839-1841; Manitowaning 1841-1859; Hon. -

How Anti-Mormons Play Word Games to Attack the Latter-Day Saints

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 1992 Offenders for a Word: How Anti-Mormons Play Word Games to Attack the Latter-Day Saints Daniel C. Peterson Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Daniel C. and Ricks, Stephen D., "Offenders for a Word: How Anti-Mormons Play Word Games to Attack the Latter-Day Saints" (1992). Maxwell Institute Publications. 57. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/57 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Introduction The somewhat cryptic title of this work—Offenders for a Word—comes from the twenty-ninth chapter of the book of Isaiah, a chapter that is not only replete with prophecies of the restoration of the gospel and the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, but with predictions of the kind of opposition that would greet the latter-day work. Much of this opposition, as we are convinced and attempt to show in the pages that follow, rests upon the manipulation of language, upon illegitimate semantic games that truly make innocent people “offenders for a word.” While we are condent that our conclusions are fully justied by the evidence as well as by reason, we are aware that these conclusions may seem controversial to some of our readers. In order to avoid the possible suggestion of tendentiousness in our renderings of early Christian materials, we have generally followed standard English translations of these sources, rather than providing our own.