Aspects of Foraging in Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) Inferred from Nuclear 18S Ribosomal DNA (18S Rdna) Sequences

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 25 (2002) 535–544 www.academicpress.com Phylogenetic analysis of anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) inferred from nuclear 18S ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) sequences Peter H.H. Weekers,a,* Gopal Murugan,a,1 Jacques R. Vanfleteren,a Denton Belk,b and Henri J. Dumonta a Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium b Biology Department, Our Lady of the Lake University of San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78207, USA Received 20 February 2001; received in revised form 18 June 2002 Abstract The nuclear small subunit ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) of 27 anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) belonging to 14 genera and eight out of nine traditionally recognized families has been sequenced and used for phylogenetic analysis. The 18S rDNA phylogeny shows that the anostracans are monophyletic. The taxa under examination form two clades of subordinal level and eight clades of family level. Two families the Polyartemiidae and Linderiellidae are suppressed and merged with the Chirocephalidae, of which together they form a subfamily. In contrast, the Parartemiinae are removed from the Branchipodidae, raised to family level (Parartemiidae) and cluster as a sister group to the Artemiidae in a clade defined here as the Artemiina (new suborder). A number of morphological traits support this new suborder. The Branchipodidae are separated into two families, the Branchipodidae and Ta- nymastigidae (new family). The relationship between Dendrocephalus and Thamnocephalus requires further study and needs the addition of Branchinella sequences to decide whether the Thamnocephalidae are monophyletic. Surprisingly, Polyartemiella hazeni and Polyartemia forcipata (‘‘Family’’ Polyartemiidae), with 17 and 19 thoracic segments and pairs of trunk limb as opposed to all other anostracans with only 11 pairs, do not cluster but are separated by Linderiella santarosae (‘‘Family’’ Linderiellidae), which has 11 pairs of trunk limbs. -

Black Oystercatcher

Alaska Species Ranking System - Black Oystercatcher Black Oystercatcher Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Haematopus bachmani Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 08 April 2019 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5 ADF&G: Species of Greatest Conservation Need IUCN: Audubon AK: S Rank: S2S3B,S2 USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 11 Action -40 to 40 -4 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Suspected stable (ASG 2019; Cushing et al. 2018), but data are limited and do not encompass this species' entire range. We therefore rank this question as Unknown. Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Habitat is dynamic and subject to change as a result of geomorphic and glacial processes. For example, numbers expanded on Middleton Island after the 1964 earthquake (Gill et al. 2004). Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -2 Uncertain. The global population is estimated at 11,000 individuals, of which 45%-70% breed in Alaska (ASG 2019). -

Black Oystercatcher Diet and Provisioning 2014 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Black Oystercatcher Chick Diet and Provisioning 2014 Annual Report Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KEFJ/NRDS—2015/749 ON THIS PAGE Nest camera captures a black oystercatcher provisioning chick on Natoa Island. Photograph Courtesy: NPS/Kenai Fjords National Park ON THE COVER Black oystercatchers at nest in Aialik Bay, Kenai Fjords National Park Photograph by: NPS/Katie Thoresen Black Oystercatcher Diet and Provisioning 2014 Annual Report Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KEFJ/NRDS—2015/749 Sam Stark1, Brian Robinson2 and Laura M. Phillips1 1National Park Service Kenai Fjords National Park PO Box 1727 Seward, AK 99664 2 University of Alaska, Fairbanks Department of Biology and Wildlife PO Box 756100 Fairbanks, AK 99775 January 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Carcinization in the Anomura–Fact Or Fiction? II. Evidence from Larval

Contributions to Zoology, 73 (3) 165-205 (2004) SPB Academic Publishing bv, The Hague Carcinization in the Anomura - fact or fiction? II. Evidence from larval, megalopal and early juvenile morphology Patsy+A. McLaughlin Rafael Lemaitre² & Christopher+C. Tudge² ¹, 1 Shannon Point Marine Center, Western Washington University, 1900 Shannon Point Road, Anacortes, 2 Washington 98221-908IB, U.S.A; Department ofSystematic Biology, NationalMuseum ofNatural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, U.S.A. Keywords: Carcinization, Anomura, Paguroidea, Lithodidae, Paguridae, Lomisidae, Porcellanidae, larval, megalopal and early juvenile morphology, pleonal tergites Abstract Existing hypotheses 169 Developmental data 170 Results 177 In this second carcinization in the Anomura ofa two-part series, From hermit to king, or king to hermit? 179 has been reviewed from early juvenile, megalopal, and larval Analysis by Richter & Scholtz 179 perspectives. Data from megalopal and early juvenile develop- Questions of asymmetry- 180 ment in ten ofthe Lithodidae have genera provided unequivo- Pleopod loss and gain 18! cal evidence that earlier hypotheses regarding evolution ofthe Uropod loss and transformation 182 king crab erroneous. of and pleon were A pattern sundering, - Polarity or what constitutes a primitive character decalcification has been traced from the megalopal stage through state? 182 several early crabs stages in species ofLithodes and Paralomis, Semaphoronts 184 with evidence from in other supplemental species eight genera. Megalopa/early juvenile characters and character Of major significance has been the attention directed to the states 185 inmarginallithodidsplatesareofnotthehomologoussecond pleomere,with thewhichadult whenso-calledseparated“mar- Cladistic analyses 189 Lomisoidea 192 ginal plates” ofthe three megalopal following tergites. -

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds

CHAPTER 1 General introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds, sometimes referred to as waders, are birds that rely on coastal beaches, shorelines, estuaries and mudflats, or inland lakes, lagoons and the like for part of, and in some cases all of, their daily and annual requirements, i.e. food and shelter, breeding habitat. They are of the suborder Charadrii and include the curlews, snipe, plovers, sandpipers, stilts, oystercatchers and a number of other species, making up a diverse group of birds. Within Australia, shorebirds account for 10% of all bird species (Lane 1987) and in New South Wales (NSW), this figure increases marginally to 11% (Smith 1991). Of these shorebirds, 45% rely exclusively on coastal habitat (Smith 1991). The majority, however, are either migratory or vagrant species, leaving only five resident species that will permanently inhabit coastal shorelines/beaches within Australia. Australian resident shorebirds include the Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus neglectus), Hooded Plover (Charadrius rubricollis), Red- capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus), Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris) and Sooty Oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus) (Smith 1991, Priest et al. 2002). These species are generally classified as ‘beach-nesting’, nesting on sandy ocean beaches, sand spits and sand islands within estuaries. However, the Sooty Oystercatcher is an island-nesting species, using rocky shores of near- and offshore islands rather than sandy beaches. The plovers may also nest by inland salt lakes. Shorebirds around the globe have become increasingly threatened with the pressure of predation, competition, human encroachment and disturbance and global warming. Populations of birds breeding in coastal areas which also support a burgeoning human population are under the highest threat. -

Introduction

BlackOystercatcher — BirdsofNorthAmericaOnline Page1of2 From the CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY and the AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS'UNION. species or keywords Search Home Species Subscribe News & Info FAQ Already a subscriber? Sign in Don'thave a subscription? Subscribe Now Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani Order CHARADRIIFORMES –Family HAEMATOPODIDAE Issue No.155 Authors:Andres, Brad A.,and Gary A.Falxa • Articles • Multimedia • References Articles Introduction Welcome to the Birds of North America Online! Welcome to BNA Online, the leading source of life history information for North American breeding birds.This free, Distinguishing Characteristics courtesy preview is just the first of 14articles that provide detailed life history information including Distribution, Migration, Distribution Habitat, Food Habits, Sounds, Behavior and Breeding.Written by acknowledged experts on each species, there is also a comprehensive bibliography of published research on the species. Systematics Migration A subscription is needed to access the remaining articles for this and any other species.Subscription rates start as low as $5USD for 30days of complete access to the resource.To subscribe, please visit the Cornell Lab of Ornithology E-Store. Habitat Food Habits If you are already a current subscriber, you will need to sign in with your login information to access BNA normally. Sounds Subscriptions are available for as little as $5for 30days of full access!If you would like to subscribe to BNA Online, just Behavior visit the Cornell Lab of Ornithology E-Store. Breeding Introduction Demography and Populations Conservation and Management Appearance Measurements Priorities for Future Research Acknowledgments About the Author(s) Black Oystercatcher in flight, Pt.Pinos, Monterey, California, 18February 2007. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/155/articles/introduction 11/14/2015 BlackOystercatcher — BirdsofNorthAmericaOnline Page2of2 Fig.1.Distribution of the Black Oystercatcher. -

Crabs and Their Relatives of British Columbia by Josephine Hart 1984 British Columbia Provincial Museum Handbook 40

Crabs and their relatives of British Columbia by Josephine Hart 1984 British Columbia Provincial Museum Handbook 40. Victoria, British Columbia. 267 pp. Extracted from the publication (now out of print) SECTION MACRURA Superfamily Thalassinidea Key to Families 1. Shrimp-like. Integument soft and pleura on abdomen large. Live in burrows……………………………………………………………………………..……….……Axiidae 1. Shrimp-like. Integument soft and pleura small. Live in burrows………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 2. Rostrum distinct, ridged and setose. Eyestalks cylindrical and cornea terminal. Chelipeds subchelate and subequal…………………………………………………………………….Upogebiidae 2. Rostrum minute and smooth. Eyestalks flattened with mid-dorsal corneal pigment or cylindrical without dark pigment. Chelipeds chelate and unequal in size and shape.......Callianassidae Family AXIIDAE The thin-shelled shrimp-like animals in this family are all burrowers and are found from shallow subtidal habitats to great depths. Recently Pemberton, Risk and Buckley (1976) determined that one species found off Nova Scotia makes burrows more than 2.5 m into the substrate. Obviously in abyssal regions the collection of these animals under such circumstances in particularly haphazard. Thus the number of specimens obtained is few and often these are damaged. Four species of this family are known to occur in the waters off British Columbia. All have one or two small hollow knobs of apparently unknown function on the mid-dorsal ridge of the carapace. These species have been assigned to the genera Axiopsis, Calastacus and Calocaris. The definitions of these genera were made when few species had been studied and recent discoveries indicate that the criteria used are not satisfactory. New genera will have to be created and the taxonomy of the Family revised. -

Black Oystercatcher Foraging Hollenberg and Demers 35

Black Oystercatcher foraging Hollenberg and Demers 35 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) foraging on varnish clams (Nuttallia obscurata) in Nanaimo, British Columbia Emily J. R. Hollenberg 1 and Eric Demers 2 1 4063905 Quadra St., Victoria, B.C., V8X 1J1; email: [email protected] 2 Corresponding author: Biology Department, Vancouver Island University, 900 Fifth St., Nanaimo, B.C., V9R 5S5; email: [email protected] Abstract: In this study, we investigated whether Black Oystercatchers (Haematopus bachmani) feed on the recently intro duced varnish clam (Nuttallia obscurata), and whether they selectively feed on specific size classes of varnish clams. Sur veys were conducted at Piper’s Lagoon and Departure Bay in Nanaimo, British Columbia, between October 2013 and February 2014. Foraging oystercatchers were observed, and the number and size of varnish clams consumed were recor ded. We also determined the density and size of varnish clams available at both sites using quadrats. Our results indicate that Black Oystercatchers consumed varnish clams at both sites, although feeding rates differed slightly between sites. We also found that oystercatchers consumed almost the full range of available clam sizes, with little evidence for sizeselective foraging. We conclude that Black Oystercatchers can successfully exploit varnish clams and may obtain a significant part of their daily energy requirements from this nonnative species. Key Words: Black Oystercatcher, Haematopus bachmani, varnish clam, Nuttallia obscurata, foraging, Nanaimo. Hollenberg, E.J.R. and E. Demers. 2017. Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) foraging on varnish clams (Nuttallia obscurata) in Nanaimo, British Columbia. British Columbia Birds 27:35–41. Campbell et al. -

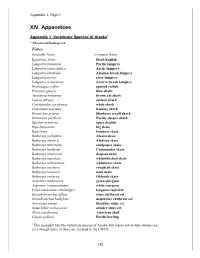

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

The Transport of Marine Life Across the Ocean on Tsunami Marine Debris 東日本大震災による津波にともなう漂着瓦礫がもたらした 海洋無脊椎動物の越境移動について

The Transport of Marine Life Across the Ocean on Tsunami Marine Debris 東日本大震災による津波にともなう漂着瓦礫がもたらした 海洋無脊椎動物の越境移動について Saturday, May 20, 2017 James T. Carlton (Williams College, USA) John Chapman Oregon State University Jonathan Geller Moss Landing Marine Laboratories Jessica Miller Oregon State University Gregory Ruiz Smithsonian Environmental Research Center Our first “meeting” (encounter) in North America with Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris (JTMD): June 5, 2012, in Oregon • On the morning of Tuesday, June 5, 2012 • 451 days (14 1/2 months) after March 11, 2011 …….. • Morning beach walkers reported that a “large dock” had floated ashore near Newport, Oregon Port of Misawa, built 2008 7,000 km journey across the Pacific Ocean 2.2 meters 20 meters 5.8 meters The dock attracted much public attention, with more than 20,000 visitors in the summer of 2012 Mediterranean mussel Wakame Mytilus galloprovincialis Undaria pinnatifida 10s of 1000s of mussels dense layers of seaweed Inside the dock: the Japanese seastar (starfish) Asterias amurensis Examples of coastal organisms on “Misawa 1”: Landed Agate Beach, Oregon, June 4, 2012 Sea urchin Temnotrema sculptum Sea cucumber Havelockia Seastar Asterias Shore crab versicolor Semibalanus amurensis Hemigrapsus Megabalanus ECHINODERMS sanguineus cariosus rosa Crab BARNACLES Sea squirts Oedignathus Styela sp. inermis Oyster128 different species of Crassostrea Jassa marmorata, Jingle shell Japanese animals andKelp plants Ampithoe valida, gigas Anomia crossed the oceanUndaria to Halichondria Caprella spp. Cytaeum pinnatifida and 3 other AMPHIPODS (chinensis) North Americaand 29 species other species SPONGES BRYOZOANS: on ”Misawaof algae1” Chiton Clam Tricellaria, Mopalia Hiatella orientalis Cryptosula HYDROIDS spp. , seta Snail Mussels: (8 species) Watersipora Mitrella Mytilus galloprovincialis, moleculina M. -

AFRICAN Black OYSTERCATCHER

1 1 2 2 3 3 4 African Black Oystercatcher 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 8 Between 8 9 9 10 10 11 the tides 11 12 Text by Phil Hockey 12 13 13 14 he African Black Oystercatcher’s 14 15 15 first entry into the scientific ‘led- 16 16 17 ger’ happened only 141 years 17 18 T 18 19 ago, when a specimen collected at the 19 20 Cape of Good Hope was described by 20 21 21 22 Bonaparte. Bonaparte named the bird 22 23 moquini after the French botanist, 23 24 24 25 Horace Benedict Alfred Moquin Tandon, 25 26 director of the Toulouse Botanical 26 27 27 28 Gardens. Its first entry into the litera- 28 29 29 ture, however, predates this by more 30 30 31 than 200 years. 31 32 32 33 In 1648, Étienne de Flacourt, the 33 34 Governor-General of Madagascar, 34 35 35 36 visited Saldanha Bay. He wrote: ‘There 36 37 are birds like blackbirds, with a very shrill 37 38 38 39 and clear cry, as large as partridges, with 39 40 40 a long sharp beak and red legs: they are 41 41 42 very good to eat and when young they 42 43 43 44 taste like Woodcock’. The first descrip- 44 45 tions of the bird’s biology date from the 45 46 46 47 late 19th century – much of what was 47 48 written then was culled from knowledge 48 49 49 50 of the European Oystercatcher, and much 50 51 51 of it was wrong! 52 52 53 Now, at the end of the 20th century, it 53 54 54 55 seems as though this striking bird may 55 56 be moving from a confused past into an 56 57 57 58 uncertain future.