Playing Guqin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur Gmbh the World's Oldest Accordion

MADE IN GERMANY Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH The world’s oldest accordion manufacturer | Since 1852 Our “Weltmeister” brand is famous among accordion enthusiasts the world over. At Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH, we supply the music world with Weltmeister solo, button, piano and folklore accordions, as well as diatonic button accordions. Every day, our expert craftsmen and accordion makers create accordions designed to meet musicians’ needs. And the benchmark in all areas of our shop is, of course, quality. 160 years of instrument making at Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH in Klingenthal, Germany, are rooted in sound craftsmanship, experience and knowledge, passed down carefully from master to apprentice. Each new generation that learns the trade of accordion making at Weltmeister helps ensure the longevity of the company’s incomparable expertise. History Klingenthal, a centre of music, is a small town in the Saxon Vogtland region, directly bordering on Bohemia. As early as the middle of the 17th century, instrument makers settled down here, starting with violin makers from Bohemia. Later, woodwinds and brasswinds were also made here. In the 19th century, mouth organ ma- king came to town and soon dominated the townscape with a multitude of workshops. By the year 1840 or thereabouts, this boom had turned Klingenthal into Germany’s largest centre for the manufacture of mouth organs. Production consolidation also had its benefits. More than 30 engineers and technicians worked to stre- Accordion production started in 1852, when Adolph amline the instrument making process and improve Herold brought the accordion along from Magdeburg. quality and customer service. A number of inventions At that time the accordion was a much simpler instru- also came about at that time, including the plastic key- ment, very similar to the mouth organ, and so it was board supported on two axes and the plastic and metal easily reproduced. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

TV Show Knows What's in Your Fridge Is Food for Thought

16 | Wednesday, June 17, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY YOUTH ometimes you have to travel didn’t enjoy traditional Chinese to appreciate your own. music that much until he pursued his Sometimes, waking up in a music studies in the United States. foreign land gives you a pre- When leaving China, he took with Scious insight into your own country. him the hulusi, a kind of Chinese Fang Songping is a musician and wind instrument made from a has traveled but when he was at gourd, and played it recreationally home with his pipa-player father, in the college. The exotic sound of Fang Jinlong, he preferred Western the instrument won him lots of fans rock. and requests to perform on stage. It was hulusi, the gourd-like Then he started researching about instrument, that really changed his traditional Chinese music and com- life. He happened to bring it to Los bining elements of it into his own Angeles, while studying music there. compositions. In 2015, he returned His classmates were fascinated to China and started his career as an when he played music with it, and a indie musician. new horizon opened up before him. Now, Fang Songping works as the According to a recent report on music director of a popular reality traditional Chinese music, young show, Gems of Chinese Poetry, Chinese people are turning their which centers on traditional Chi- attention to traditional arts. More nese arts, such as poetry, music, and more are listening to traditional dance and paintings. He composed Chinese music. eight original instrumental pieces, The report was released on June inspired by traditional Chinese cul- 2, under the guidance of the China ture, like music, chess, calligraphy Association of Performing Arts, by and paintings. -

Singapore Chinese Orchestra Instrumentation Chart

Singapore Chinese Orchestra Instrumentation Chart 王⾠威 编辑 Version 1 Compiled by WANG Chenwei 2021-04-29 26-Musician Orchestra for SCO Composer Workshop 2022 [email protected] Recommendedabbreviations ofinstrumentnamesareshown DadiinF DadiinG DadiinA QudiinBb QudiinC QudiinD QudiinEb QudiinE BangdiinF BangdiinG BangdiinA XiaodiinBb XiaodiinC XiaodiinD insquarebrackets ˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ 2Di ‹ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ [Di] ° & ˙ (Transverseflute) & ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ¢ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ b˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ s˙ounds 8va -DiplayerscandoubleontheXiaoinForG(samerangeasDadiinForG) -ThischartnotatesmiddleCasC4,oneoctavehigherasC5etc. #w -WhileearlycompositionsmightdesignateeachplayerasBangdi,QudiorDadi, -8va=octavehigher,8vb=octavelower,15ma=2octaveshigher 1Gaoyin-Sheng composersareactuallyfreetochangeDiduringthepiece. -PleaseusethetrebleclefforZhonghupartscores [GYSh] ° -Composerscouldwriteonestaffperplayer,e.g.Di1,Di2andspecifywhentousewhichtypeofDi; -Pleaseusethe8vbtrebleclefforZhongyin-Sheng, (Sopranomouthorgan) & ifthekeyofDiislefttotheplayers'discretion,specifyatleastwhetherthepitchshould Zhongyin-GuanandZhongruanpartscores w soundasnotatedor8va. w -Composerscanrequestforamembranelesssound(withoutdimo). 1Zhongyin-Sheng -WhiletheDadiandQudicanplayanother3semitonesabovethestatedrange, [ZYSh] theycanonlybeplayedforcefullyandthetimbreispoor. -ForeachkeyofDi,thesemitoneabovethelowestpitch(e.g.Eb4ontheDadiinG)sounds (Altomouthorgan) & w verymuffledduetothehalf-holefingeringandisunsuitableforloudplaying. 低⼋度发⾳ ‹ -Allinstrumentsdonotusetransposednotationotherthantranspositionsattheoctave. -

Three Millennia of Tonewood Knowledge in Chinese Guqin Tradition: Science, Culture, Value, and Relevance for Western Lutherie

Savart Journal Article 1 Three millennia of tonewood knowledge in Chinese guqin tradition: science, culture, value, and relevance for Western lutherie WENJIE CAI1,2 AND HWAN-CHING TAI3 Abstract—The qin, also called guqin, is the most highly valued musical instrument in the culture of Chinese literati. Chinese people have been making guqin for over three thousand years, accumulating much lutherie knowledge under this uninterrupted tradition. In addition to being rare antiques and symbolic cultural objects, it is also widely believed that the sound of Chinese guqin improves gradually with age, maturing over hundreds of years. As such, the status and value of antique guqin in Chinese culture are comparable to those of antique Italian violins in Western culture. For guqin, the supposed acoustic improvement is generally attributed to the effects of wood aging. Ancient Chinese scholars have long discussed how and why aging improves the tone. When aged tonewood was not available, they resorted to various artificial means to accelerate wood aging, including chemical treatments. The cumulative experience of Chinese guqin makers represent a valuable source of tonewood knowledge, because they give us important clues on how to investigate long-term wood changes using modern research tools. In this review, we translated and annotated tonewood knowledge in ancient Chinese books, comparing them with conventional tonewood knowledge in Europe and recent scientific research. This retrospective analysis hopes to highlight the practical value of Chinese lutherie knowledge for 21st-century instrument makers. I. INTRODUCTION In Western musical tradition, the most valuable musical instruments belong to the violin family, especially antique instruments made in Cremona, Italy. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music -

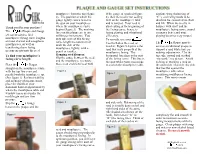

Thank You for Your Purchase! the ® Plaque and Gauge Set Can Be Used to Find Mouthpiece Facing Curve Lengths on Most Clarinet A

mouthpiece from the top (figure If the gauge is crooked (figure airplane wing (balancing of 2). The position at which the 4), then the reed is not sealing “C”), each wing needs to be ® gauge lightly comes to rest is well on the mouthpiece table identical for consistent air-flow MADE IN USA the spot on your mouthpiece and is warped. Your reed is and lift. When the reed is in Thank you for your purchase! where the mouthpiece curve also leaking at the beginning of balance with itself and the begins (figure 3). The marking the facing curve, hence, is mouthpiece facing curve, sound The ® Plaque and Gauge lines on the plaque are in one losing playing and vibrational resonates better and your set can be used to find millimeter increments. You efficiency. playing becomes very natural. mouthpiece facing curve lengths may take note of this facing To remedy, use your ® on most clarinet and saxophone curve length measurement or Tool to flatten the reed, as The ® Plaque may be mouthpieces, as well as mark the side of the transferring those facing needed. Figure 5 depicts a flat used as a traditional plaque to mouthpiece, lightly, with a reed that seals properly at the support a reed while you are measurements onto the reed. pencil or marker. mouthpiece facing. The making adjustments. Use the To find your mouthpiece’s Gauging reed flatness: horizontal line depicts the start top side, curved end marked facing curve length: Slip the gauge between the reed of the facing curve. This line is “tip work,” see picture. -

Bishop Scott Boys' School

BISHOP SCOTT BOYS’ SCHOOL (Affiliated to CBSE, New Delhi) Affiliation No.: 330726, School Campus: Chainpur, Jaganpura, By-Pass, Patna 804453. Phone Number: 7061717782, 9798903550. , Web: www.bishopscottboysschool.com Email: [email protected] STUDY COURSE MATERIAL ENGLISH SESSION-2020-21 CLASS- IX Ch 2- The Sound of Music. Part I - (Evelyn Glennie Listens to Sound without Hearing It) By Deborah Cowley Part I. Word meanings. 1. Profoundly deaf: absolutely deaf. 2. specialist: a doctor specializing in a particular part of the body. 3. Deteriorated: worsened, reduces. 4. Urged: requested. 5. coveted: much desired 6. replicating: making a copy of something 7. yearning – longing, having a desire for something 8. devout: believing strongly in a religion and obeying its laws and following its practices Summary. Evelyn Glennie is a multi – percussionist. She has attained mastery over almost a thousand musical instruments despite being hearing – impaired. She learnt to feel music through the body instead of hearing it through the ears. When Evelyn was eleven years old, it was discovered that she had lost her hearing power due to nerve damage. The specialist advised that she wear hearing aids and be sent to a school for the deaf. On the contrary, Evelyn was determined to lead a normal life and follow her interest in music. Although she was discouraged by her teachers, her potential was noticed by master percussionist, Ron Forbes. He guided Evelyn to feel music some other way than to hear it through her ears. This worked well for Evelyn and she realized that she could sense different sounds through different parts of her body. -

Video Competition 2020

VIDEO COMPETITION 2020 ABOUT: The United States International Music Competition is organized by the United States International Music Foundation affiliated with the Chinese Music Teachers’ Association of Northern California, a non-profit organization. This competition provides young musicians with an opportunity to exhibit their talents and reward their hard work, as well as to encourage them to appreciate cross-cultural exchanges . ELIGIBILITY: Contestants of all nationalities.No Age Limit. Past First Place winners may not compete in an age group that they have won previously. However, they may elect to compete in another age-appropriate group. INSTRUMENT CATEGORIES: Piano (Solo, Duet, and Concerto), Violin, Viola, Cello, Classical Chamber Ensembles (Western Instruments), Vocal (Solo and Ensemble), Marimba, and Traditional Chinese Instruments categories are held annually. Harp and Classical Guitar are also included in the 2020 competition categories. AGE GROUPS: Eligibility for each group will be determined by the contestant’s age as of June 1, 2020. Each instrument category has different age groups. Category & Piano Violin Viola Cello Vocal Age groups A Age 9 or under Age 9 or under Age 14 or under Age 11 or under Age 9 or under B Age 11 or under Age 13 or under Age 18 or under Age 14 or under Age 12 or under C Age 14 or under Age 18 or under Age 19 or above Age 18 or under Age 14 or under D Age 18 or under Age 19 or above Age 19 or above Age 18 or under E Age 19 or above Age 19 or above Piano Duet Category -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin.