Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHINIOT, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE for RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 15Th, 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: CHINIOT, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 15th, 2014 Rains/Floods 2014: Chiniot District Profile September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionRajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Police Station Phone No. Population (2013 est) 1,180,200 Circles/ Circles/ Male 612,924 (52%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- SDPO City Circle 0476-332930 Tapas urban populated Female 567,276 (48%) City 0476-331520 DISTRICT 13 115 361 347 3 4 1 6 Rural 1,465,614 (78%) Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 Sadar 0476-331540 Urban 403,807 (22%) Rajoa 0346-5833304 Tehsils 3 Road Network Infrastructure UC 45 District Route Length SDPO Chanab Nagar Circle 0476-214890 Revenue Villages 361 Chiniot to Faislabad Narwala road 44 Km Chanab Nagar 0476-213175 Chiniot to Jhang Jhang- Chiniot road 123 Km Area (Sq km) 2,610.28 Police Post Chanab Nagar 0476-213176 Chiniot to Sargodha Faisalabad road 77.3 Km Registered Voters (ECP) 587,962 Chiniot to Hafizabad Lahore road 171 Km Lalian 0476-610210 Literacy Rate 10+ (PSLM 2010-11) 47% Chiniot-Lahore Lahore - Islamabad Motorway/AH1 161 KM Barrana 0300-8644435 Source: Google Maps Departmental Focal Points Kandiwal 0321-6000844 Entry-Exit Points SDPO Bhawana Circle 0476-201515 Designation Contacts 1 Lalian 4 Aminpur Commissioner, Faisalabad Division 041-9201701, 041-9201702 2 Jaisal 5 Chak 223 Bhawana 0476-201040 DCO, Chiniot 047-6330071 EDO(H) 0476-330106 3 Muhammad -

Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport

Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport A Case Report: Faisalabad, Pakistan Atta Ullah Khan assisted by Wajid Hassan Edited by M. Sohail Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University 2003 Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK © WEDC, Loughborough University, 2003 Any part of this publication, including the illustrations (except items taken from other publications where the authors do not hold copyright) may be copied, reproduced or adapted to meet local needs, without permission from the author/s or publisher, provided the parts reproduced are distributed free, or at cost and not for commercial ends, and the source is fully acknowledged as given below. Please send copies of any materials in which text or illustrations have been used to WEDC Publications at the address given above. Atta Ullah Khan assisted by Wajid Hassan (2003) Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport - A Case Report: Faisalabad, Pakistan Series Editor: M. Sohail A reference copy of this publication is also available online at: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/wedc/publications/piaqpt-pakistan ISBN Paperback 1 84380 038 1 This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of low-income countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Designed and produced at WEDC by Glenda McMahon, Sue Plummer and Rod Shaw List of maps and figures Map 1.1. Faislabad: Land use map ....................................................................4 Map 1.2. Location of Katchi Abadies ..................................................................6 Map 2.1. -

Impact of Urbanization on Political Culture a Case Study of Faisalabad City

International Journal of Educational Science and Research (IJESR) ISSN 2249-6947 Vol. 3, Issue 2, Jun 2013, 69-74 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. IMPACT OF URBANIZATION ON POLITICAL CULTURE A CASE STUDY OF FAISALABAD CITY MUGHEES AHMED1 & RAHEELAASFA2 1Chairman/Associate Professor, Department of Political Science & International Relations, Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan 2Lecturer, Department of Political Science & International Relations, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT This study proposed a model of individual voter behavior that can be applied to aggregate data at the urban area levels while accounting for differences in political preferences across rural, regions and across voters within each district. How political preferences in Faisalabad deviate from the average voterand how each candidate outfits to average voter preferences withindistrict. The voter first evaluates the candidatesto decide whether or not to cast his vote, and then choosesthe candidate who provides him with the highest value. Unobservable voters within each urban and rural area may be observed through the study of their voting behavior. In this study impact of urbanization on voting behavior of the voters of district Faisalabad is discussed. Analytical and behavioral approach is adopted in this piece of work KEYWORDS: Analytical and Behavioral Approach, Sandhilianwali, Arab Baddu Race INTRODUCTION Settlement Faisalabad is situated in central Punjab.This district consists of six sub-divisions. The people of Sandal Bar (Before1891 this area was vast tropical forest called Sandal bar) belonged to Arab Baddu race. According to census of 1891 its population was 64,610.1 The real work of colonization began in February 1892. In a letter No. 327 of 22nd July 1891, from the Revenue Secretary, Punjab Government explained as follows the principles for the distribution of the land. -

Locus of Control in Graduation Students

I N T E R N A T I O N A L J O U R N A L O F R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E P S Y C H O L O G I C A L R E S E A R C H Locus of Control in Graduation Students Locus de Control en Estudiantes de Graduación Imran Haider Zaidi , a, M. Naeem Mohsin b a MS (Clinical Psychology) Scholar G.C University, Faisalabad, Pakistan b Director Distance Learning Education G.C University, Faisalabad, Pakistan The current research focused on exploring the direction of Locus of control as well as gender difference on locus of control among graduation students in Pakistan. A 29 item Locus of Control questionnaire (Rotter, 1966) was used to measure locus of control. Key Words: Sample of (N=200) individuals (n=100) men and (n=100) women selected from different academic institutes of Faisalabad division Punjab Pakistan. Independent sample t-test Locus of control, was used for statistical analysis. This study has consistent results with the earlier graduation, students, studies. Results of this research indicate that men has internal locus of control and Punjab, Pakistan. women scored high on external locus of control. So the gender difference is significant on Locus of Control. Implications of these findings and suggestions for future researches are discussed. La presente investigación se enfoca en explorar tanto la dirección como la diferencia de género del Locus de Control entre estudiantes de graduación en Pakistán. Un cuestionario de Locus de Control de 29 ítems (Rotter, 1966) fue usado para medir el Palabras Clave: Locus de Control de la muestra (N=200,) conformada por hombres(n=100) y mujeres (n=100) seleccionados de diferentes instituciones académicas de Faisalabab en la Locus de Control, provincia de Punjab Pakistán. -

Faisalabad Division Demand of Ctis for the Year 2018-19

DEMAND OF CTIS FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 FAISALABAD DIVISION TOTAL Subject in which CTIs TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Sr. No. Name of College TEACHER Required ENROLMENT SANCTIONED RECOMMENDED WORKING 1 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Biology 367 1 1 1 2 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Botany 340 1 1 1 3 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Chemistry 786 4 4 1 4 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Computer Science 1056 2 2 1 5 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad English 3637 15 11 2 6 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Education 1129 2 2 1 7 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Mathmatics 938 4 4 1 8 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Physics 930 3 3 2 9 Govt. Islamia College for Women, Faisalabad Zoology 394 0 0 2 TOTAL 12 1 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. Biology 600 2 2 2 2 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. Comp. Science 1320 1 1 4 3 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. Commerce 371 0 0 3 4 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. English 3412 8 8 5 5 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. Fine Arts 217 0 0 4 Islamic Education /Islamic 6 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. 2574 3 3 2 studies 7 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. Mass Communication 160 0 0 3 8 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. Mathematics/Buisness Math 850 2 2 2 9 Govt. College for women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad. -

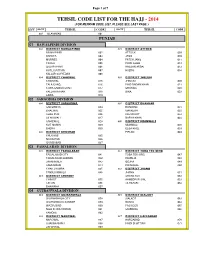

Tehsil Code List for the Hajj

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ - 2014 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Directorate General Health Services Punjab

0 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES PUNJAB. D.G.H.S Office [DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES, PUNJAB] Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. DGHS, Punjab. 1. 042 99201139-40 (PSO) 99201139-40 ( P.A ) 2. 042 Fax 99201142 99238505 3. DHS (HQ) 042 99201141 DHS (EPI) 99201143 4. 042 99202812 Fax 99200405 ADG (Dengue) (EP&C) 99203235 042 5. Fax 99203235 DHS (P&D) 6. 042 99203793 7. DHS (MIS) 042 99205510 Program Manager( NCD) 8. 042 9. DHS (Dental). 042 99203751 Director (Pharmacy) 99201145 042 10. 99204622 DHS (CDC) 11. 042 99200970 DHS (TB). 35408894 12. 042 Fax 99203750 Director (Accounts). 13. 042 99202487 Additional Director (Admn). 99200987 14. 042 Fax 99201095 36118382 Res Additional Director (EPI) 15. 042 99200535 Additional Director (Malaria ) 16. 042 99202970 A. D (F&N/NCD) 99203749 042 17. Fax. 99204190 (Micronutrient) 99204014 18. 042 36290201 Fax Addl. Director (IRMNCH) 99205330-26 19. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 1 Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. Addl. Director-I, IRMNCH 99200982 20. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 P.M Hepatitis 21. 042 99204129 Addl. Director (MS&DC) 22. 042 99203505 Usman Ghani 23. 042 99200969 Additional Director (H.E). Media Manager 24. 042 99200969 Additional Director (TB-DOTS) 25. 042 99203750 Transport Manager, TMO 26. Workshop 042 35155845 27. (Supt.TPT) Budget & Accounts Officer 28. 042 99203487 Additional Director (Homeo) Shahid (Homeo Dr) 29. 042 99204191 Litigation Officer 30. Mr.Imran Ur Rehman 042 99200983 Computer Programer 31. 042 99200990 G.M (MSD) 35758336 32. 042 35873989 99201257 33. Bacteriologist 042 99200108 PD (HIV/AIDS). -

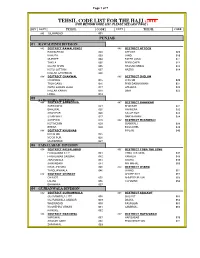

Tehsil Code List 2014

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ -2016 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Formerly Faisalabad Cattle Market Management Company 2Nd Floor, Commissioner Office, Civil Lines, Faisalabad Division

Punjab Cattle Market Management & Development Company (PCMMDC) Formerly Faisalabad Cattle Market Management Company 2nd Floor, Commissioner Office, Civil Lines, Faisalabad Division. Phone No. 041-9201767 Corrigendum Hiring of Tents & Other Services Reference to the tender for “Hiring of Tents & Other Services” uploaded on PPRA’s website dated June 15, 2021 by the Punjab Cattle Market Management & Development Company- Faisalabad Division. List of Works/Services has been revised, as per detail given below:- Sr # Item / Description 1 Tents including Peg & Rope 15x15 (Complete Job) 2 Kanat (Complete Job) Tent (Canopy) including Peg & Rope 45x45 (Complete 3 Job) 4 Chairs high back Foam with Cover 5 Table Wooden Standard size With Cover 6 Steel Water Tanks (Hamam) with stand for Hand Wash 7 Generator 100 KVA with Diesel Tent (Canopy) including Peg & Rope 60x90 (Complete 8 Job) Rate of above Items will be mentioned for Cattle Markets of Faisalabad Division, as per given below:- Model Sr. Item / Quantity Cattle Mamu Shorkot Jaranwala Samundari Chiniot Lalian # Description (Nos.) Market, Kanjan City Niamoana Tents including Peg & Rope 1 Per unit 15x15 (Complete Job) Kanat 2 (Complete Per unit Job) Punjab Cattle Market Management & Development Company (PCMMDC) Formerly Faisalabad Cattle Market Management Company 2nd Floor, Commissioner Office, Civil Lines, Faisalabad Division. Phone No. 041-9201767 Tent including Peg & Rope 3 Per unit 45x45 (Complete Job) Chairs high 4 back Foam Per unit with Cover Table Wooden 5 Standard Per unit size With Cover Steel Water Tanks 6 (Hamam) Per unit for Hand Wash Generator 7 Per unit 100 KVA 8 Diesel Per Hour Tent including Peg & Rope 9 Per unit 60x90 (Complete Job) Other terms & Conditions will remain same. -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs. -

Baseline Assessment Study Report District Jhang

BBaasseelliinnee AAsssseessssmmeenntt SSttuuddyy RReeppoorrtt District Jhang (1) Ver 2.00 Update on 10-Feb-09 Sr. # CONTENTS Page # 1 Key Counterparts in Government 3 2 Map 3 3 Summary 4 4 Situation Analysis 7 5 Table 1: Tehsils & Unions in the District 7 5 Table 2: Population Size And Growth Of Major Cities 8 Table 3: Socio Economic Indicators, Coverage (Vis-1Vis Punjab), Ranking , 6 8 MDG Targets MICS (2003-04) District-wise Data 7 Table 4: Literacy Ratio Ranking Of Punjab Districts (Age 10 years & above) 9 8 Table 4a: Population That Has Ever Attended School 9 9 Table 4b: Literacy-Population 10 Years And Older 9 10 Table 4c: Gross Enrolment Rate At The Primary Level 9 11 Table 4d: Net Enrolment Rate At The Primary Level 9 12 Table 5: Institutions by Level, Gender, Location and Sector(Public) 10 13 Table 6: Enrolment by Stage, Gender, Location and Public Sector 11 14 Table 7: Teachers by Level, Gender, Location and Sector 11 15 Table 8: Physical Facilities by Level and Gender (Public) 12 16 Table 9: Status of Public Schools by National, Provincial and District 13 Table 10: Sanctioned, Filled-in, Vacant and Contract Teacher's Posts by Level 17 13 and Gender (Public) 18 Table 11: OXFAM Project List of selected Schools 14 19 Table 12: Summary of School Baseline Survey Report (WSIP Schools) 15 20 Table 13: Summary of School Baseline Survey - Cluster Schools 17 21 Table 13a: Summary of School Councils – WSIP Schools 22 22 District Based Baseline Reports on Learning Levels 23 23 Table 14: Summary of Learning Levels WSIP Schools 25 24 Table -

DIRECTORATE of EDUCATION (COLLEGES), FAISALABAD DIVISION FAISALABAD College Wise Demand of Ctis-2020-21 (FOR FEMALE COLLEGES)

DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (COLLEGES), FAISALABAD DIVISION FAISALABAD College Wise Demand of CTIs-2020-21 (FOR FEMALE COLLEGES) Subject No. of teachers Total no. of CTIs Sr. CMIS No. of students in Open Merit Minority Disabled Name of the College Division District in which CTI is already Working required No Code the Subject (92%) Quota (5%) Quota (3%) required in Subject in the Subject 1 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad Biology 1 768 1 1 - - 2 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad Commerce 0 374 1 - 1 - 3 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad Computer Science 1 865 1 1 - - 4 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad English 8 3300 2 2 - - 5 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad Fine Arts 0 210 1 1 - - 6 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad Islamiat 3 2000 1 1 - - Mass 7 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad 0 200 1 1 - - Communication 8 331108 Govt College for Women Karkhana Bazar Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad Mathematics 2 992 1 1 - - Govt. Islamia College for Women, Eidgah Road, 9 331109 Faisalabad Faisalabad Botany 1 800 1 1 - - Faisalabad Govt. Islamia College for Women, Eidgah Road, 10 331109 Faisalabad Faisalabad Zoology 0 412 1 - - 1 Faisalabad Human Nutrition and 11 331128 Govt. Home Economics College, Faisalabad Faisalabad Faisalabad 0 84 1 1 - - Dietetics Govt.Degree College (W) 61/jb Narwala Banglow 12 331402 Faisalabad Faisalabad English 1 1100 1 1 - - Faisalabad.