<I>Shrek</I> As Ethical Fairy Tale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

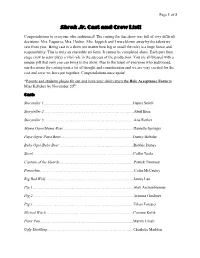

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Shrek Audition Monologues

Shrek Audition Monologues Shrek: Once upon a time there was a little ogre named Shrek, who lived with his parents in a bog by a tree. It was a pretty nasty place, but he was happy because ogres like nasty. On his 7th birthday the little ogre’s parents sat him down to talk, just as all ogre parents had for hundreds of years before. Ahh, I know it’s sad, very sad, but ogres are used to that – the hardships, the indignities. And so the little ogre went on his way and found a perfectly rancid swamp far away from civilization. And whenever a mob came along to attack him he knew exactly what to do. Rooooooaaaaar! Hahahaha! Fiona: Oh hello! Sorry I’m late! Welcome to Fiona: the Musical! Yay, let’s talk about me. Once upon a time, there was a little princess named Fiona, who lived in a Kingdom far, far away. One fateful day, her parents told her that it was time for her to be locked away in a desolate tower, guarded by a fire-breathing dragon- as so many princesses had for hundreds of years before. Isn’t that the saddest thing you’ve ever heard? A poor little princess hidden away from the world, high in a tower, awaiting her one true love Pinocchio: (Kid or teen) This place is a dump! Yeah, yeah I read Lord Farquaad’s decree. “ All fairytale characters have been banished from the kingdom of Duloc. All fruitcakes and freaks will be sent to a resettlement facility.” Did that guard just say “Pinocchio the puppet”? I’m not a puppet, I’m a real boy! Man, I tell ya, sometimes being a fairytale creature sucks pine-sap! Settle in, everyone. -

Shrek Jr. (Ages 6-18; All Youth Are Cast)

Shrek Jr. (ages 6-18; all youth are cast) Beauty is in the eye of the ogre in Shrek The Musical JR., based on the Oscar-winning DreamWorks Animation film and fantastic Broadway musical. It's a "big bright beautiful world" as everyone's favorite ogre, Shrek, leads a cast of fairytale misfits on an adventure to rescue a princess and find true acceptance. Part romance and part twisted fairy tale, Shrek JR. is an irreverently fun show with a powerful message for the whole family. Once upon a time, in a faraway swamp, there lived an ogre named Shrek. One day, Shrek finds his swamp invaded by banished fairytale misfits who have been cast off by Lord Farquaad, a tiny terror with big ambitions. When Shrek sets off with a wisecracking donkey to confront Farquaad, he's handed a task — if he rescues feisty princess Fiona, his swamp will be righted. Shrek tries to win Fiona’s love and vanquish Lord Farquaad, but a fairytale wouldn't be complete without a few twists and turns along the way. Storytellers Wonderful roles for performers with natural stage presence and big, clear voices. These characters are important for setting up the world and moving the story forward. Bold, energetic young actors. Gender: Any Shrek He may be a big, scary, green ogre to the rest of the world, but as the story reveals, he's really just a big fellow with a big heart. Excellent actor and strong singer with comedic chops. Gender: Male Fiona She may appear to be an ideal princess straight from the fairy tale books, but there is more to her than that stereotypical image. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release DATE: September 2016 CONTACT: Kori Radloff, [email protected], 402-502-4641 The Rose Theater announces the cast of Shrek The Musical Robby Stone Nik Whitcomb Lauren Krupski Brian Guehring Sue Gillespie Booton Colleen Kilcoyne Shrek Donkey Fiona Lord Farquaad Dragon Gingy (OMAHA, Nebr.) An ornery ogre, a peculiar princess, a talking donkey, a vertically- challenged villain and a love struck dragon are headed to The Rose Theater with the production of Shrek The Musical. The Broadway sensation, based on DreamWorks Animation’s 2001 blockbuster Shrek will run at The Rose, Sept. 30 through Oct. 15, 2016. The Rose is proud to announce the cast of Shrek The Musical. The cast consists of several Rose Theater favorites. Robby Stone (Honk, Peter & the Starcatcher, Big Nate, Jackie & Me) will bring the green ogre to life. Nik Whitcomb (Pete the Cat, Sherlock Holmes & the First Baker Street Irregular, Honk) plays Shrek’s sidekick Donkey. Princess Fiona will be played by Lauren Krupski (Cat in the Hat, Pete the Cat, A Christmas Story). Three Rose teaching artists will also be featured on stage: Brian Guehring (Robin Hood, Honk, Mary Poppins) as Lord Farquaad, Sue Gillespie Booton (Pete the Cat, Cat in the Hat) as Dragon, and Colleen Kilcoyne (Honk) as Gingy. Rounding out the adult cast are Jennifer Castello and Regina Palmer. Of special note, the cast includes several alumni and current participants of The Rose’s Teens ‘N’ Theater program. Shrek The Musical also features 12 youth performers who will share various roles throughout the show. = MORE = The Rose Theater t (402) 345-4849 2001 Farnam Street f (402) 344-7255 Omaha, NE 68102 www.rosetheater.org The Rose Theater announces Shrek cast Page 2 of 3 Contact: Kori Radloff, 402-502-4641 Shrek The Musical is based on the popular DreamWorks Animation movie. -

Mcdonald's® “SHREK the THIRD™” HAPPY MEAL® FACT SHEET

McDONALD’S® “SHREK THE THIRD™” HAPPY MEAL® FACT SHEET “Talk” about fun! McDonald’s “Shrek the Third” Happy Meal collection features 11 talking toys that capture the exciting personalities of the film’s main characters. Each talking character will leave young guests and their families laughing all the way home as the toys repeat signature phrases straight from the silver screen. LANGUAGES: The new Happy Meal collection marks the first fully talking toy collection for McDonald’s that is available in eight different languages that speak in children’s native language. The toys are available around the world in English, Spanish-Mexico, Spanish-Castilian/Spain, French, German, Portuguese, Mandarin and Japanese. ABOUT THE TOYS: Shrek® – Featuring an ogre-like stance, Shrek® lets out one of three signature phrases at the push of a button, including “I’m an ogre!” and “I’m on it.” Puss In Boots® – This fierce feline is a true scene-stealer. Rotate his left arm to hear suave comments such as “Fear me if you dare” and “I gotta go.” Donkey – The ultimate fairy tale sidekick, Donkey certainly loves to talk. Young guests can press Donkey’s tail to enjoy hilarious key phrases such as “Peek-a-boo,” “Are we there yet?” and “Shrek!” Gingy® – A fairy tale favorite, this pint-sized cookie character includes moveable arms and classic features. With the press of his purple gumdrop button, Gingy’s signature voice exclaims, “Not my gumdrop buttons!” and “Don’t worry.” Artie – The possible future king of Far Far Away is reluctant to take the throne. -

Mixed Metaphors and Dear Characters

Founded April 14,1975 Banned from Box Hill, 1989 - Returned to Box Hill, 1998 Run 1735 Link to SH3OnSec Homepage Date 13-Jul-08 Grand Master : Hare Teq & Chunderos MIXED METAPHORS AND FRB (Peter Hughes) Venue Headley Park DEAR CHARACTERS 01932 886 747 (h) On On Headley Park Club hashers know that trails laid by a catch up with NH4, Returners, Joint Masters: hare on a bike are characterised by and characters like Captain Hook SBJ If the proverb that “The sun being slightly too long, lacking (AKA Ancient Mariner) and Reg (Fran Ridout shines on the righteous” is true, serious shiggy and no stiles. Thus, of the River (TBR “Reg of the 07793 462 919(m) then Teq and Chunderos definitely it should have been deduced by the Pond). The hash was started early and cannot be sinners. Slotting an Portaloo pack that a trail laid from an by King Harold (AKA FRB) outdoor performance of Antony Emergent Hashbulance must be obviously worried that he would (Bob Wood) and Cleopatra, a 100th birthday 01737 842 945 (h) anticipated to have similar, but miss the banquet later. To party and a hash between the superlative, characteristics, i.e. discourage Lord Farquaad from Religious Advisor : “thundery showers” forecast, this slightly more than slightly too carping, Shrek had laid some Bonn Bugle week, without getting completely long, rather more black-top than monstrous back-checks to keep (Jo Avey) inundated, must require some form shiggy and… absolutely NO style. the pack together – which worked. 07718 903 493 (m) of divine intervention. So with Unfortunately, he relied on the Apollo and Amun Ra obviously on This might seem slightly harsh intelligence of the pack to solve Clutcher’s Mate : their side, the SH3 version of but, if writing something positive these which didn’t work quite so Hornblower Antony and Cleopatra should have about Bodyshop’s offering last well – thus the two hour trail. -

Sesiune Speciala Intermediara De Repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009

Sesiune speciala intermediara de repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009 TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 A1 A2 3:00 a.m. 3 A.M. 2001 US Lee Davis Lee Davis 04:30 04:30 2005 SG Royston Tan Royston Tan Liam Yeo 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 1941 1941 1979 US Steven Bob Gale Robert Zemeckis (Trecut, prezent, viitor) (Past Present Future) Imperfect Imperfect 2004 GB Roger Thorp Guy de Beaujeu 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - Roger Bruce Feirstein - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Spottiswoode ALCS 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales 101 Dalmatians - One Hamilton Luske - Hundred and One Hamilton S. Wolfgang Bill Peet - William 101 dalmatieni Dalmatians 1961 US Clyde Geronimi Luske Reitherman Peed EG/FR/ GB/IR/J Alejandro Claude Marie-Jose 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/ Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Claude Lelouch Danis Tanovic - Sanselme - Paul Laverty - Samira septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 US Inarritu Mira Nair SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS -

Turning Student Dreams Into Creative Careers Creative Professionals Share Insight Into “A Day in the Life” As Part of Student Voices Summit

Media Contact: Toni Robin TR/PR Public Relations 858-483-3918 [email protected] Turning Student Dreams into Creative Careers Creative Professionals Share Insight into “A Day in the Life” as part of Student Voices Summit March 30, 2017 – Los Angeles - This year’s Student Voices Summit & Screening, the culmination event for a year-long campaign engaging middle and high school students in filmmaking, advocacy and leadership in their local school district will feature an opportunity for students to gain insight into how their creative pursuits can lead to creative careers. An inspiring panel of professionals will share their stories and then meet with students for more personal conversations and questions. Featured on the “A Day in the Life” panel will be representatives from the world of film, TV, music and fashion with professionals from Dreamworks, Boeing and General Motors. In Los Angeles alone, creative industry fields produced more than 418,000 jobs from 2009 to 2015. Research also points to the fact that K-12 participation in media, architecture and product design classes is growing. Our Creative Career Mentors will share their share their stories and offer students insight into what made a vital difference in their success. The goal is to introduce young people to a variety of creative careers, to give them strategies to pursue them and to allow them to see themselves in these roles. The team of professionals features people of color, women and others who are underrepresented in this field. The “Day in the Life” panel will be moderated by Priska Neely, Arts Education Reporter, 89.3 KPCC, Southern California Public Radio. -

Nine February

MAGAZINE NINE FEBRUARY... “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema...” (BBC) FEBRUARY 2010 Issue 59 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6pm Sun 4.30-6.30pm To advertise email [email protected] INTRODUCTION Gallery 4-5 February Evenings 7 Coming Soon 21 February Films at a glance 21 February Matinees 23 Rants and Pants 38-39 SEAT PRICES: Circle £8.00 Concessions £6.50 At Table £10.00 Concessions £8.50 Royal Box (seats 6) £12.00 or for the Box £66.00 All matinees £5, £6.50, £10 (box) BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30 – 6.00 Sun 4.30 – 6.30 Disabled and flat access: through the gate on High Street (right of apartments) Some of the girls and boys you see at the Box Office and Bar: Rosie Abbott Malcolm More Julia Childs Liam Parker Nicola Darvell Hannah Pedder Lindsey Davies Izzi Robinson Holly Gilbert Amberly Rose Katie Golder Georgia Rose Beth Hannaway Diya Sagar Natalie Jones Alice Spooner Amelia Kellett Liam Stephenson Abbie Knight Tina Thorpe Bethany McKay Jack Whiting Simon Messenger Olivia Wilson Helen Miller Keymea Yazdanian Ushers: Abigail K, Ally, Billie, Charlotte, Ellie, Emma, James, Kitty, Lucy, Luisa, Lydia K, Romy, Roz, Sid Sally Thorpe In charge Alun Rees Chief projectionist (Original) (Top) Ian Dury’s New Boots and Panties album Jon Waugh 1st assistant projectionist cover loyally recreated with the young Baxter Martin Coffill Part-time assistant projectionist Jacquie Rose Chief Box Office & Bar finally growing in to those bell-bottoms. Oliver Hicks Best Boy (Bottom) A beautifully shot and underrated big Becca Ross Best Girl screen thriller.