Bilateral Pleural Effusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleural Effusion and Ventilation/Perfusion Scan Interpretation for Acute Pulmonary Embolus

ventricular function by radionuclide angiography during exercise in normal subjects 33. Verani MS. Myocardial perfusion imaging versus two-dimensional echocardiography: and patients with chronic coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983;1:1518- comparative value in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. J NucÃCardiol 1529. 1994;1:399-414. 29. Adam WE. Tarkowska A, Bitter F, Stauch M, Geffers H. Equilibrium (gated) 34. Foster T, McNeill AJ, Salustri A, et al. Simultaneous dobutamine stress echocardiog radionuclide ventriculography. Cardiovasc Radial 1979;2:161-173. raphy and technetium-99m SPECT in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. 30. Hurwitz RA, TrêvesS, Kuroc A. Right ventricular and left ventricular ejection fraction J Am Coll Cardiol I993;21:1591-I596. in pediatrie patients with normal hearts: first pass radionuclide angiography. Am 35. Marwick TH, D'Hondt AM, Mairesse GH, Baudhuin T, Wijins W, Detry JM, Meiin Heart J 1984;107:726-732. 31. Freeman ML, Palac R, Mason J, et al. A comparison of dobutamine infusion and JA. Comparative ability of dobutamine and exercise stress in inducing myocardial ischemia in active patients. Br Heart J 1994:72:31-38. supine bicycle exercise for radionuclide cardiac stress testing. Clin NucÃMed 1984:9:251-255. 36. Senior R, Sridhara BS, Anagnostou E, Handler C, Raftery EB, Lahiri A. Synergistic 32. Cohen JL, Greene TO, Ottenweller J, Binebaum SZ, Wilchfort SD, Kim CS. value of simultaneous stress dobutamine sestamibi single-photon-emission computer Dobutamine digital echocardiography for detecting coronary artery disease. Am J ized tomography and echocardiography in the detection of coronary artery disease. -

Chylothorax After Left Side Pneumothorax Surgery Managed by OK-432 Pleurodesis: an Effective Alternative

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 77 (2014) 653e655 www.jcma-online.com Case Report Chylothorax after left side pneumothorax surgery managed by OK-432 pleurodesis: An effective alternative Sheng-Yang Huang a, Chou-Ming Yeh b, Chia-Man Chou a,c,*, Hou-Chuan Chen a a Division of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, ROC b Taichung Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taichung, Taiwan, ROC c National Yang-Ming University School of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC Received June 13, 2013; accepted September 23, 2013 Abstract Chylothorax, a relatively rare complication of thoracic surgery, mostly occurs on the right side. We present a 16-year-old male who received thoracoscopic surgery for left spontaneous pneumothorax. Chylothorax developed on the postoperative 2nd day and resolved after diet control on the 4th day. Unfortunately, chylothorax recurred 2 weeks later. Chest drainage and nil per os with total parental nutrition were given but in vain. Thereafter, chemical pleurodesis with OK-432 was performed. Chylothorax resolved on the next day. The relevant literature is reviewed and possible pathogenesis clarified. Copyright © 2014 Elsevier Taiwan LLC and the Chinese Medical Association. All rights reserved. Keywords: chylothorax; pleurodesis; pneumothorax 1. Introduction 2. Case Report Postoperative chylothorax is infrequent but potentially A 16-year-old male patient had the history of left chest pain life-threatening and time-consuming to manage. Associated for 5 days. -

Section 8 Pulmonary Medicine

SECTION 8 PULMONARY MEDICINE 336425_ST08_286-311.indd6425_ST08_286-311.indd 228686 111/7/121/7/12 111:411:41 AAMM CHAPTER 66 EVALUATION OF CHRONIC COUGH 1. EPIDEMIOLOGY • Nearly all adult cases of chronic cough in nonsmokers who are not taking an ACEI can be attributed to the “Pathologic Triad of Chronic Cough” (asthma, GERD, upper airway cough syndrome [UACS; previously known as postnasal drip syndrome]). • ACEI cough is idiosyncratic, occurrence is higher in female than males 2. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • Afferent (sensory) limb: chemical or mechanical stimulation of receptors on pharynx, larynx, airways, external auditory meatus, esophagus stimulates vagus and superior laryngeal nerves • Receptors upregulated in chronic cough • CNS: cough center in nucleus tractus solitarius • Efferent (motor) limb: expiratory and bronchial muscle contraction against adducted vocal cords increases positive intrathoracic pressure 3. DEFINITION • Subacute cough lasts between 3 and 8 weeks • Chronic cough duration is at least 8 weeks 4. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS • Respiratory tract infection (viral or bacterial) • Asthma • Upper airway cough syndrome (postnasal drip syndrome) • CHF • Pertussis • COPD • GERD • Bronchiectasis • Eosinophilic bronchitis • Pulmonary tuberculosis • Interstitial lung disease • Bronchogenic carcinoma • Medication-induced cough 5. EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF THE COMMON CAUSES OF CHRONIC COUGH • Upper airway cough syndrome: rhinitis, sinusitis, or postnasal drip syndrome • Presentation: symptoms of rhinitis, frequent throat clearing, itchy -

Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism M Riedel

309 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.2003.007955 on 10 June 2004. Downloaded from REVIEW Diagnosing pulmonary embolism M Riedel ............................................................................................................................... Postgrad Med J 2004;80:309–319. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.007955 Objective testing for pulmonary embolism is necessary, embolism have a low long term risk of subse- quent VTE.2 5–7 because clinical assessment alone is unreliable and the consequences of misdiagnosis are serious. No single test RISK FACTORS AND RISK has ideal properties (100% sensitivity and specificity, no STRATIFICATION risk, low cost). Pulmonary angiography is regarded as the The factors predisposing to VTE broadly fit Virchow’s triad of venous stasis, injury to the final arbiter but is ill suited for diagnosing a disease vein wall, and enhanced coagulability of the present in only a third of patients in whom it is suspected. blood (box 1). The identification of risk factors Some tests are good for confirmation and some for aids clinical diagnosis of VTE and guides decisions about repeat testing in borderline exclusion of embolism; others are able to do both but are cases. Primary ‘‘thrombophilic’’ abnormalities often non-diagnostic. For optimal efficiency, choice of the need to interact with acquired risk factors before initial test should be guided by clinical assessment of the thrombosis occurs; they are usually discovered after the thromboembolic event. Therefore, the likelihood of embolism and by patient characteristics that risk of VTE is best assessed by recognising the may influence test accuracy. Standardised clinical presence of known ‘‘clinical’’ risk factors. estimates can be used to give a pre-test probability to However, investigations for thrombophilic dis- orders at follow up should be considered in those assess, after appropriate objective testing, the post-test without another apparent explanation. -

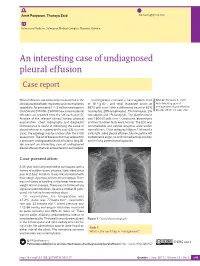

An Interesting Case of Undiagnosed Pleural Effusion Case Report

Amit Panjwani, Thuraya Zaid [email protected] Pulmonary Medicine, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Manama, Bahrain. An interesting case of undiagnosed pleural effusion Case report Pleural effusions are commonly encountered in the Investigations revealed a haemoglobin level Cite as: Panjwani A, Zaid T. clinical practise of both respiratory and nonrespiratory of 16.4 g⋅dL−1, and total leukocyte count of An interesting case of specialists. An estimated 1–1.5 million new cases in 8870 cells⋅mm−3 with a differential count of 62% undiagnosed pleural effusion. the USA and 200 000–250 000 new cases of pleural neutrophils, 28% lymphocytes, 7% monocytes, 2% Breathe 2017; 13: e46–e52. effusions are reported from the UK each year [1]. eosinophils and 1% basophils. The platelet count Analysis of the relevant clinical history, physical was 160 000 cells⋅mm−3. Creatinine, electrolytes examination, chest radiography and diagnostic and liver function tests were normal. The ECG was thoracentesis is useful in identifying the cause of unremarkable and cardiac enzymes were within pleural effusion in majority of the cases [2]. In a few normal limits. Chest radiograph (figure 1) showed a cases, the aetiology may be unclear after the initial mild, right-sided pleural effusion, blunting of the left assessment. The list of diseases that may account for costophrenic angle, no shift of mediastinal position a persistent undiagnosed pleural effusion is long [3]. and no lung parenchymal opacities. We present an interesting case of undiagnosed pleural effusion that was encountered in our hospital. R Case presentation A 33-year-old male presented to our hospital with a history of sudden-onset, pleuritic, right-sided chest pain of 2 days’ duration. -

PICTORIAL REVIEW Thoracic Involvement in Connective

JBR–BTR, 2015, 98: 3-19. PICTORIAL REVIEW THORACIC INVOLVEMENT IN CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASES: RADIO- LOGICAL PATTERNS AND FOLLOW-UP G. Serra1, A.-L. Brun1, P. Ialongo2, M.-L. Chabi1, P.A. Grenier1 Connective tissue diseases (CTDs) are a heterogeneous group of idiopathic inflammatory diseases involving various organs. A thoracic involvement is frequent, and chest-CT represents the imaging technique of reference in its assess- ment. Pulmonary abnormalities related to CTDs are various; although several disease-specific aspects have been described, the two most clinically relevant complications are represented by interstitial lung disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension. The early identification of a thoracic involvement, with the adoption of specific therapies, can significantly change patient’s prognosis. The aim of this article is to review the most common typical and atypical CT features of thoracic involvement occurring in CT, especially focusing on interstitial lung disease. Key-word: Connective tissue, diseases – Lung, interstitial disease – Hypertension, pulmonary. Connective tissue diseases (CTDs) at the time of diagnosis of CTD, or chronic inflammation in the alveolar are a heterogeneous group of in- more commonly manifest later in the walls. The patients usually response flammatory diseases derived from course of the disease (5, 6). well to corticosteroid therapy and an immunologic deregulation affect- The most common histopatholog- have a good prognosis. However pa- ing various organs. A thoracic in- ic patterns of ILD seen in the setting tients with OP associated with CTD volvement (pulmonary, pleural or of CTDs are non specific interstitial seem to have a greater tendency to mediastinal) can be frequently pneumonia (NSIP), usual interstitial develop fibrosis and a higher mortal- found; its frequency and expression pneumonia (UIP), organizing pneu- ity than patients with cryptogenic depends on the type of disease, and monia (OP), diffuse alveolar damage OP (5, 6). -

Diagnosis of Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension After Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Early View Review Diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism Fredrikus A. Klok, Francis Couturaud, Marion Delcroix, Marc Humbert Please cite this article as: Klok FA, Couturaud F, Delcroix M, et al. Diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J 2020; in press (https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00189-2020). This manuscript has recently been accepted for publication in the European Respiratory Journal. It is published here in its accepted form prior to copyediting and typesetting by our production team. After these production processes are complete and the authors have approved the resulting proofs, the article will move to the latest issue of the ERJ online. Copyright ©ERS 2020 Diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism Fredrikus A. Klok, Francis Couturaud F2, Marion Delcroix M3, Marc Humbert4-6 1 Department of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands 2 Département de Médecine Interne et Pneumologie, Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire de Brest, Univ Brest, EA 3878, CIC INSERM1412, Brest, France 3 Department of Respiratory Diseases, University Hospitals and Respiratory Division, Department of Chronic Diseases, Metabolism & Aging, KU Leuven – University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium 4 Université Paris-Saclay, Faculté de Médecine, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France 5 Service de Pneumologie et Soins Intensifs Respiratoires, Hôpital Bicêtre, AP-HP, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France 6 INSERM UMR S 999, Hôpital Marie Lannelongue, Le Plessis Robinson, France Corresponding author: Frederikus A. Klok, MD, FESC; Department of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands; Albinusdreef 2, 2300RC, Leiden, the Netherlands; Phone: +31- 715269111; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is the most severe long-term complication of acute pulmonary embolism (PE). -

Chylothorax As Rare Manifestation of Pleural Involvement in Waldenström Macroglobulinemia: Mechanisms and Management

210 Lymphology 49 (2016) 210-217 CHYLOTHORAX AS RARE MANIFESTATION OF PLEURAL INVOLVEMENT IN WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA: MECHANISMS AND MANAGEMENT G. Leoncini, C.C. Campisi, G. Fraternali Orcioni, F. Patrone, F. Ferrando, C. Campisi Unit of Thoracic Surgery (GL), Unit of General & Lymphatic Surgery - Microsurgery and Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics (DISC) (CCC,CC), Unit of Pathology (GFO), Unit of Internal Medicine and Medical Oncology and Department of Internal Medicine (DIMI) (FP,FF), IRCCS San Martino University Hospital - National Institute for Cancer Research, and University School of Medicine and Pharmaceutics, Genoa, Italy ABSTRACT increase of IgM level. Pleuropulmonary involvement is reported to be rare (from 0 Here we report the clinical, pathological, to 5% of cases), and it usually occurs during and immunological features of a rare case of the late phase of the disease (3,4). In such a Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) with scenario, chylothorax is rarely observed in pleural infiltrations. An atypical chylothorax, WM patients; indeed only seven cases have successfully treated by videothoracoscopy, been reported in the literature (5-11). We represented the main clinical feature of this report the case of a 66-year old man with the case of low-grade lymphoplasmacytic main clinical presentation of pleural lymphoma. Pleuropulmonary manifestations infiltrations with right chylothorax following are rare (from 0 to 5% of cases) in WM, with immunochemotherapy. An extra-bone chylothorax observed in just seven patients marrow involvement was suggested by both worldwide. In addition to describing this pleural fluid examination and multiple uncommon clinical presentation, we investi- pleural biopsies in parallel with a marked gate hypothetical pathogenetic mechanisms decrease of bone marrow (BM) participation causing chylothorax and through an up-to- (tumor cells in BM from 70% to 8%). -

Management of Malignant Pleural Effusions an Official ATS/STS/STR Clinical Practice Guideline David J

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY DOCUMENTS Management of Malignant Pleural Effusions An Official ATS/STS/STR Clinical Practice Guideline David J. Feller-Kopman*, Chakravarthy B. Reddy*, Malcolm M. DeCamp, Rebecca L. Diekemper, Michael K. Gould, Travis Henry, Narayan P. Iyer, Y. C. Gary Lee, Sandra Z. Lewis, Nick A. Maskell, Najib M. Rahman, Daniel H. Sterman, Momen M. Wahidi, and Alex A. Balekian; on behalf of the American Thoracic Society, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society of Thoracic Radiology THIS OFFICIAL CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE WAS APPROVED BY THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY OCTOBER 2018, THE SOCIETY OF THORACIC SURGEONS JUNE 2018, AND THE SOCIETY OF THORACIC RADIOLOGY JULY 2018 Background: This Guideline, a collaborative effort from the MPE; 3) using either an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) or American Thoracic Society, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and chemical pleurodesis in symptomatic patients with MPE and Society of Thoracic Radiology, aims to provide evidence-based suspected expandable lung; 4) performing large-volume recommendations to guide contemporary management of patients thoracentesis to assess symptomatic response and lung expansion; with a malignant pleural effusion (MPE). 5) using either talc poudrage or talc slurry for chemical pleurodesis; 6) using IPC instead of chemical pleurodesis in patients with Methods: A multidisciplinary panel developed seven questions nonexpandable lung or failed pleurodesis; and 7) treating using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, and IPC-associated infections with antibiotics and not removing the Outcomes) format. The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, catheter. Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach and the Evidence to Decision framework was applied to each question. Recommendations Conclusions: These recommendations, based on the best available were formulated, discussed, and approved by the entire panel. -

Respiratory Function Changes After Asbestos Pleurisy

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.35.1.31 on 1 January 1980. Downloaded from Thorax, 1980, 35, 31-36 Respiratory function changes after asbestos pleurisy P H WRIGHT, A HANSON, L KREEL, AND L H CAPEL From the Cardiothoracic Institute, London Chest Hospital, East Ham Chest Clinic, London, and the Division of Radiology, Clinical Research Centre, Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow ABSTRACT Six patients with radiographic evidence of diffuse pleural thickening after industrial asbestos exposure are described. Five had computed tomography of the thorax. All the scans showed marked circumferential pleural thickening often with calcification, and four showed no significant evidence of intrapulmonary fibrosis (asbestosis). Lung function testing showed reduc- tion of the inspiratory capacity and the single-breath carbon monoxide transfer factor (TLco). The transfer coefficient, calculated as the TLCO divided by the alveolar volume determined by helium dilution during the measurement of TLco, was increased. Pseudo-static compliance curves showed markedly more negative intrapleural pressures at all lung volumes than found in normal people. These results suggest that the circumferential pleural thickening was preventing normal lung expansion despite abnormally great distending pressures. The pattern of lung function tests is sufficiently distinctive for it to be recognised in clinical practice, and suggests that the lungs are held rigidly within an abnormal pleura. The pleural thickening in our patients may have been related to the condition described as "benign asbestos pleurisy" rather than the copyright. interstitial fibrosis of asbestosis. Malignant pleural effusion associated with meso- necessary in many of these early cases, and opera- thelioma or bronchial carcinoma is a recognised tion notes recorded the presence of marked http://thorax.bmj.com/ complication of asbestos exposure. -

Occupational Lung Diseases

24 Occupational lung diseases Introduction i Occupational diseases are often thought to be Key points uniquely and specifically related to factors in the work environment; examples of such diseases are • Systematic under-reporting and the pneumoconioses. However, in addition to other difficulties in attributing causation both contribute to underappreciation of the factors (usually related to lifestyle), occupational burden of occupational respiratory exposures also contribute to the development or diseases. worsening of common respiratory diseases, such • Work-related exposures are estimated as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), to account for about 15% of all adult asthma and lung cancer. asthma cases. • Boththe accumulation of toxic dust in the Information about the occurrence of occupational lungs and immunological sensitisation respiratory diseases and their contribution to to inhaled occupational agents can morbidity and mortality in the general population is cause interstitial lung disease. provided by different sources of varying quality. Some • Despite asbestos use being phased European countries do not register occupational out, mesothelioma rates are forecast diseases and in these countries, information about to continue rising owing to the long latency of the disease. the burden of such diseases is completely absent. • The emergence of novel occupational In others, registration is limited to cases where causes of respiratory disease in compensation is awarded, which have to fulfil specific recent years emphasises the need for administrative or legal criteria as well as strict continuing vigilance. medical criteria; this leads to biased information and underestimation of the real prevalence. Under- reporting of occupational disease is most likely to occur in older patients who are no longer at work but whose condition may well be due to their previous job. -

Acute Pulmonary Embolism in Patients with and Without COVID-19

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Acute Pulmonary Embolism in Patients with and without COVID-19 Antonin Trimaille 1,2 , Anaïs Curtiaud 1, Kensuke Matsushita 1,2 , Benjamin Marchandot 1 , Jean-Jacques Von Hunolstein 1 , Chisato Sato 1,2, Ian Leonard-Lorant 3, Laurent Sattler 4 , Lelia Grunebaum 4, Mickaël Ohana 3 , Patrick Ohlmann 1 , Laurence Jesel 1,2 and Olivier Morel 1,2,* 1 Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg University Hospital, 67000 Strasbourg, France; [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (K.M.); [email protected] (B.M.); [email protected] (J.-J.V.H.); [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (P.O.); [email protected] (L.J.) 2 INSERM (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research), UMR 1260, Regenerative Nanomedicine, FMTS, 67000 Strasbourg, France 3 Radiology Department, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg University Hospital, 67000 Strasbourg, France; [email protected] (I.L.-L.); [email protected] (M.O.) 4 Haematology and Haemostasis Laboratory, Centre for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg University Hospital, 67000 Strasbourg, France; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (L.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Introduction. Acute pulmonary embolism (APE) is a frequent condition in patients with Citation: Trimaille, A.; Curtiaud, A.; COVID-19 and is associated with worse outcomes. Previous studies suggested an immunothrombosis Matsushita, K.; Marchandot, B.; instead of a thrombus embolism, but the precise mechanisms remain unknown.