Reform of Public Water Utilities Report of the Proceedings of a World Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design and Production of Drinking-Water Supply Network

OUR EXPERT ASSESSMENT DESIGN AND PRODUCTION OF A DRINKING-WATER SUPPLY NETWORK Especially committed to fighting water related diseases and unsanitary conditions, SOLIDARITES INTERNATIONAL (SI) has been involved in the field of access to drinking water and sanitation for almost 35 years. The annual number of deaths caused by these diseases has risen to 2.6 million, making it one of the world’s leading causes of death; amongst these victims, 1.8 million children, aged less than 15, still succumb... Today, when more than a billion people are still deprived of access to drinking water and permanently exposed to water-related diseases, the right to drinking water remains a vital concern in developing countries. In this regard, drinking-water supply networks represent quite a relevant technical solution for supplying water to refugees, as well as to dense populations and areas with high population growth. In order to further advance technical and socioeconomic diagnoses, SOLIDARITES INTERNATIONAL has led many projects, sometimes lasting years, in partnership with institutions and legitimate operators from the water sector. Hydraulic components and civil engineering relating to rehabilitation, growth and the construction of infrastructure are inseparable from the accompanying social measures, which involve placing sustainability, with the concerted management of water services and the participation of the community, at the heart of the process. Repairing, renovating or building a drinking-water network is a relevant ANALYSING AND ADAPTING technical response when the humanitarian emergency situation requires the re-establishment of the water supply and following the very first emergency TO COMPLEX measures (tanks, mobile treatment units). -

Water Supply Asset Management Plan November 2012 8.12 8.1 8.10 8.9 8.8 8.7 8.6 8.5 8.4 8.2 8.1 8

Greater Wellington Water Water Supply Asset Management Plan November 2012 Table of Contents 1. Executive summary 5 1.1 Overview 5 1.2 Asset valuation 5 1.3 Levels of service 5 1.4 Future demand 5 November 2012 1.5 Financial forecast 6 1.7 Asset management practises 6 2. Introduction 8 2.1 Asset management plan development and review process 8 2.2 Objectives of plan 8 2.3 Relationship with other plans and regulations 8 3. Business overview and activities 10 3.1 Overview of the wholesale water supply network 10 3.2 Organisational structure 13 3.3 Rationale for Greater Wellington involvement 13 3.4 Significant effects of the water supply activity 13 3.5 Key issues for activity 13 4. Levels of service 16 4.1 Identifying key stakeholders and their requirements 16 4.2 Design and consultation to define the desired service level 17 4.3 Define the current levels of service the organisation delivers 18 4.4 Measure and report to community on level of service achieved 18 5. Population and demand 20 ASSET MANAGEMENT PLAN SUPPLY WATER 5.1 Historic demand for wholesale water 20 5.2 Summer peak demand 22 5.3 Future demand drivers for wholesale water 22 5.4 Forecast demand 23 5.5 Demand management planning 24 5.6 Demand management strategies 24 6. System capacity 27 6.1 Existing system capacity 27 6.2 Meeting future demand 27 7. Risk management 30 7.1 Risk assessment of physical infrastructure 30 7.2 Asset criticality 30 7.3 Key risk mitigation measures 30 8. -

Preparing for Smart Cities Infrastructure the Mi.Net System’S Seamless Communication Capabilities Are Key to Iot, P

HELPING UTILITIES IMPLEMENT IoT-enabled Technologies ThaT provide acTionable daTa To learn more about IoT-enabled solutions, call 1.844.4.H2O.DATA Preparing for smart cities infrastructure The Mi.Net System’s seamless communication capabilities are key to IoT, p. 8 Experts weigh in on approaches and trends for building a smart water utility, p. 4 What an Internet- of-Things (IoT) driven water network looks like, p. 6 Table of Contents Common Utility Challenges How IoT and Data Are Helping Utilities ioT, or “internet of Things,” is a nexus of technologies incorporating sensor-based data gathering and next-generation networking. The smart technology platform harnesses this ioT networking through the deployment of smart devices a pUblicaTion of mueller WaTer prodUcTs using advanced wireless technologies for remote monitoring and management of water networks. This allows utilities Learn more to tackle problems facing the industry today, such as an aging workforce and the need for real-time water quality about the monitoring. below are five common challenges utilities face that can be addressed with data-driven solutions. impact of IoT In This Issue Challenge Data-Driven Solutions and data Call 1.844.4.H2O.DATA 3 Common Utility Challenges Traditionally, utilities replaced parts of their water mains or distribution networks (1.844.442.6328) to arrange for How IoT and Data are Helping Utilities without having access to information about the condition of the pipes. in many new cutting-edge technologies incorporate sensor- a customized presentation Aging cases, entire lengths of pipe were in good condition, with only parts of them needing based data gathering Infrastructure immediate replacement. -

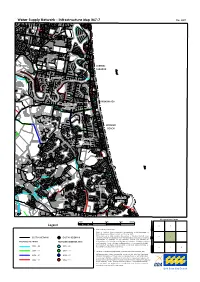

Water Supply Network - Infrastructure Map IM7-7 Dec 2007

SOUTHPORTSOUTHPORT Water Supply Network - Infrastructure Map IM7-7 Dec 2007 E BENOWABENOWA SURFERSSURFERS PARADISEPARADISE BUNDALLBUNDALL BROADBEACHBROADBEACH BROADBEACHBROADBEACH WATERSWATERS CLEARCLEAR ISLANDISLANDISLAND WATERSWATERS MERMAIDMERMAID BEACHBEACH MERMAIDMERMAID WATERSWATERS MIAMIMIAMI ROBINAROBINA BURLEIGHBURLEIGH WATERSWATERS BURLEIGHBURLEIGH STEPHENSSTEPHENS HEADSHEADS Adjoining Maps Series 1000 0 1000 2000 3000 m Legend 4 5 © Gold Coast City Council 2007 Based on Cadastral Data provided with the permission of the Department of Natural Resources and Water (current as at October 2007). While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this data, the Gold Coast 6 7 EXISTING NETWORK EXISTING RESERVIOR City Council makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all PROPOSED NETWORK PROPOSED RESERVOIR SITES responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or 2002 - 06 2002 - 06 incomplete in any way and for any reason. 8 9 10 2007 - 11 2007 - 11 © The State of Queensland (Department of Natural Resources and Water) 2007 While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this data, the Department 2012 - 21 2012 - 21 of Natural Resources and Water makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and 2022 - 51 2022 - 51 all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason. -

Moving Towards Sustainable and Resilient Smart Water Grids

Challenges 2014, 5, 123-137; doi:10.3390/challe5010123 OPEN ACCESS challenges ISSN 2078-1547 www.mdpi.com/journal/challenges Concept Paper Moving Towards Sustainable and Resilient Smart Water Grids Michele Mutchek 1 and Eric Williams 2,* 1 Department of Civil, Environmental & Sustainable Engineering, Arizona State University, Engineering G-Wing, 501 E Tyler Mall, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Golisano Institute for Sustainability, Rochester Institute of Technology, 111 Lomb Memorial Drive, Sustainability Hall, Rochester, NY 14623, USA * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-585-475-7211; Fax: +1-585-475-5455. Received: 5 October 2013; in revised form: 26 February 2014 / Accepted: 5 March 2014 / Published: 21 March 2014 Abstract: Urban water systems face sustainability and resiliency challenges including water leaks, over-use, quality issues, and response to drought and natural disasters. Information and communications technology (ICT) could help address these challenges through the development of smart water grids that network and automate monitoring and control devices. While progress is being made on technology elements, as a system, the smart water grid has received scant attention. This article aims to raise awareness of the systems-level idea of smart water grids by reviewing the technology elements and their integration into smart water systems, discussing potential sustainability and resiliency benefits, and challenges relating to the adoption of smart water grids. Water losses and inefficient use stand out as promising areas for applications of smart water grids. Potential barriers to the adoption of smart water grids include lack of funding for research and development, economic disincentives as well as institutional and political structures that favor the current system. -

A Framework for Identifying the Critical Region in Water Distribution Network for Reinforcement Strategy from Preparation Resilience

sustainability Article A Framework for Identifying the Critical Region in Water Distribution Network for Reinforcement Strategy from Preparation Resilience Mingyuan Zhang 1,* , Juan Zhang 1 , Gang Li 2 and Yuan Zhao 1 1 Department of Construction Management, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116000, China; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (Y.Z.) 2 School of Civil Engineering, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116000, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 October 2020; Accepted: 4 November 2020; Published: 6 November 2020 Abstract: Water distribution networks (WDNs), an interconnected collection of hydraulic control elements, are susceptible to a small disturbance that may induce unbalancing flows within a WDN and trigger large-scale losses and secondary failures. Identifying critical regions in a water distribution network (WDN) to formulate a scientific reinforcement strategy is significant for improving the resilience when network disruption occurs. This paper proposes a framework that identifies critical regions within WDNs, based on the three metrics that integrate the characteristics of WDNs with an external service function; the criticality of urban function zones, nodal supply water level and water shortage. Then, the identified critical regions are reinforced to minimize service loss due to disruptions. The framework was applied for a WDN in Dalian, China, as a case study. The results showed the framework efficiently identified critical regions required for effective WDN reinforcements. In addition, this study shows that the attributes of urban function zones play an important role in the distribution of water shortage and service loss of each region. -

Strategic Evaluation on Environment and Risk Prevention Under Structural and Cohesion Funds for the Period 2007-2013

Strategic Evaluation of Environment and Risk Prevention – Executive Summary STRATEGIC EVALUATION ON ENVIRONMENT AND RISK PREVENTION UNDER STRUCTURAL AND COHESION FUNDS FOR THE PERIOD 2007-2013 Contract No. 2005.CE.16.0.AT.016. National Evaluation Report for Latvia Executive Summary Directorate General Regional Policy A report submitted by in association with Mrs. Evija Brante Mr. Stijn Vermoote ELLE ECOLAS nv Skolas street 10-8 Lange Nieuwstraat 43, Riga, LV-1010 2000 Antwerp Estonia Belgium TEL +371 724.24.11 TEL +32/3/233.07.03 [email protected] [email protected] Date: November 10th, 2006 GHK Brussels Rue de la Sablonnière, 25 B-1000 Brussels Tel: +32 (0)2 275 0100; Fax : +32 (2) 2750109 GHK London 526 Fulham Road London, United Kingdom SW6 5NR Tel: +44 20 7471 8000; Fax: +44 20 7736 0784 www.ghkint.com GHK, ECOLAS, IEEP, CE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTMENT PRIORITIES IN LATVIA 1.1 PART 1: CURRENT SITUATION 1.1.1 State of the environment Water supply Available groundwater resources from the deep aquifer are abundant, with up to 4% of the resource currently being consumed, the total daily consumption being 1,4 million m³ of water. Water use in Latvia during 1990 – 2002 has decreased more than two times. Appropriate drinking water is being provided for only around 40% of the population. Most inhabitants in urban areas are provided with access to the centralised water supply network, however, much of this network is in bad technical condition and consumers may receive water of lower quality than that achieved by treatment. -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: 84065-UA INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$300 MILLION AND A PROPOSED CLEAN TECHNOLOGY FUND LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$50.00 MILLION TO UKRAINE FOR A SECOND URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT Sustainable Development Department Europe and Central Asia Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 16, 2014) Currency Unit = UAH 8.34 UAH = US$1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADSCR Annual Debt Service Coverage Ratio KfW Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau ACS Automatic Calling System Minregion Ministry of Regional Development, Construction, Housing and Communal Services BOD Biological Oxygen Demand MoE Ministry of Economic Development and Trade CO2eq CO2 equivalent MoF Ministry of Finance CPMU Central Project Management Unit MWH Megawatt Hours CPS Country Partnership Strategy NPV Net Present Value CSO Civil Society Organization NRW Non-Revenue Water CTF Clean Technology Fund O&M Operations and Maintenance DB Design-Build OCCR Operating Cost Coverage Ratio EBITDA ORAF Operational Risk Assessment Framework EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and PAP Project Affected Persons Development EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return P-RAMS Procurement Risk Assessment Module -

WATER DISTRIBUTION NETWORK REHABILITATION: Selection and Scheduling of Pipe Rehabilitation Alternatives

WATER DISTRIBUTION NETWORK REHABILITATION: Selection and Scheduling of Pipe Rehabilitation Alternatives Yehuda Kleiner A thesis subrnitted in conformity rith the requirernents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Civil Engineering University of Toronto @ copyright by Yehuda Kleiner 199 7 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 .canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 335, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KiA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfoxm, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïIm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts f?om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être Unprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Kleiner, Yehuda, 199 7. Water distribution nehvork rehabilitation: srlection and scliedding of pipe rehabilitation afrernatives.A thesis subrnitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree cf Doctor of Philosophy. Graduate Department of Civil engineering. University of Toronto. The most expensive cornponent of a water supply system is the distribution network. -

WSP) • Poorer, Dispersed, and Less Organized Communities Tend to Be Excluded; to Conceptualize a More Comprehensive Approach to PPP in the Rural Context

The Water and Sanitation Program is an ImprovingPrivate Water Operator Utility Services ModelsFebruary Forfor 200 international partnership for improving water The PoorCommunity Through Delegated Water Supply and sanitation sector policies, practices, and Management capacities to serve poor people Field Note Rural Water Supply Series A global review of private operator experiences in rural areas Private Operator Models for Community Water Supply Poor cost recovery and the ‘feast or famine’ project approach to funding have hurt the sustainability of rural water supply and impeded scaling up coverage. This Field Note highlights findings from a global review of private operator experiences in rural areas. The current rural water supply paradigm may be best described as ‘feast or famine’ project-based funding linked with community management of the installed infrastructure. a significant advantage over international Summary firms, as the scale of operations decreases. As more and more small towns come under In cities and towns, private firms and individuals receive contracts to build, improved local private sector management regimens, it is expected that PPP in the operate, and maintain municipal water supplies as an alternative to day-to- disperse rural context will expand as well. day management by local government or user organizations. A literature review has uncovered a wide variety of approaches from around the world The current rural water supply paradigm for establishing such Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) in rural areas as well. may be best described as ‘feast or famine’ project-based funding linked with Within the past seven years, several authors have completed reviews on community management of the installed private operators managing rural water supplies and other public services. -

Morphogenesis of Urban Water Distribution Networks: a Spatiotemporal Planning Approach for Cost-Efficient and Reliable Supply

entropy Article Morphogenesis of Urban Water Distribution Networks: A Spatiotemporal Planning Approach for Cost-Efficient and Reliable Supply Jonatan Zischg * , Wolfgang Rauch and Robert Sitzenfrei Unit of Environmental Engineering, University of Innsbruck, Technikerstraße 13, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] (W.R.); [email protected] (R.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-512-507-62160 Received: 26 July 2018; Accepted: 13 September 2018; Published: 14 September 2018 Abstract: Cities and their infrastructure networks are always in motion and permanently changing in structure and function. This paper presents a methodology for automatically creating future water distribution networks (WDNs) that are stressed step-by-step by disconnection and connection of WDN parts. The associated effects of demand shifting and flow rearrangements are simulated and assessed with hydraulic performances. With the methodology, it is possible to test various planning and adaptation options of the future WDN, where the unknown (future) network is approximated via the co-located and known (future) road network, and hence different topological characteristics (branched vs. strongly looped layout) can be investigated. The reliability of the planning options is evaluated with the flow entropy, a measure based on Shannon’s informational entropy. Uncertainties regarding future water consumption and water loss management are included in a scenario analysis. To avoid insufficient water supply to customers during the transition process from an initial to a final WDN state, an adaptation concept is proposed where critical WDN components are replaced over time. Finally, the method is applied to the drastic urban transition of Kiruna, Sweden. -

Urbanization and Water Privatization in the South Author(S): Karen Bakker Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

Archipelagos and Networks: Urbanization and Water Privatization in the South Author(s): Karen Bakker Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 169, No. 4 (Dec., 2003), pp. 328-341 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3451572 . Accessed: 17/08/2011 16:56 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal. http://www.jstor.org The GeographicalJournal, Vol. 169, No. 4, December2003, pp. 328-341 Archipelagosand networks: urbanization and water privatization in the South KARENBAKKER Departmentof Geography,University of BritishColumbia, 1984 WestMall, Vancouver,BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 E-mail:[email protected] Thispaper was accepted for publication in February2003 This paper examines the interrelationship between urbanization and water supply privatization in cities in the global South. The purpose of the paper is not to evaluate the impacts of privatization; rather, the paper analyses the differences in pathways and modes of water supply privatization, focusing on urban and contrasting with rural areas.