Xenophon's Hipparchikos and the Athenian Embrace Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nicholas Victor Sekunda the SARISSA

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA ARCHAEOLOGICA 23, 2001 Nicholas Victor Sekunda THE SARISSA INTRODUCTION Recent years have seen renewed interest in Philip and Alexander, not least in the sphere of military affairs. The most complete discussion of the sarissa, or pike, the standard weapon of Macedonian footsoldiers from the reign of Philip onwards, is that of Lammert. Lammert collects the ancient literary evidence and there is little one can disagree with in his discussion of the nature and use of the sarissa. The ancient texts, however, concentrate on the most remarkable feature of the weapon - its great length. Unfor- tunately several details of the weapon remain unclear. More recent discussions o f the weapon have tried to resolve these problems, but I find myself unable to agree with many of the solutions proposed. The purpose of this article is to suggest some alternative possibilities using further ancient literary evidence and also comparisons with pikes used in other periods of history. 1 do not intend to cover those aspects of the sarissa already dealt with satisfactorily by Lammert and his predecessors'. THE PIKE-HEAD Although the length of the pike is the most striking feature of the weapon, it is not the sole distinguishing characteristic. What also distinguishes a pike from a common spear is the nature of the head. Most spears have a relatively broad head designed to open a wide flesh wound and to sever blood vessels. 1 hey are usually used to strike at the unprotected parts of an opponent’s body. The pike, on the other hand, is designed to penetrate body defences such as shields or armour. -

Companion Cavalry and the Macedonian Heavy Infantry

THE ARMY OP ALEXANDER THE GREAT %/ ROBERT LOCK IT'-'-i""*'?.} Submitted to satisfy the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in the School of History in the University of Leeds. Supervisor: Professor E. Badian Date of Submission: Thursday 14 March 1974 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH X 5 Boston Spa, Wetherby </l *xj 1 West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ. * $ www.bl.uk BEST COPY AVAILABLE. TEXT IN ORIGINAL IS CLOSE TO THE EDGE OF THE PAGE ABSTRACT The army with which Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire was "built around the Macedonian Companion cavalry and the Macedonian heavy infantry. The Macedonian nobility were traditionally fine horsemen, hut the infantry was poorly armed and badly organised until the reign of Alexander II in 369/8 B.C. This king formed a small royal standing army; it consisted of a cavalry force of Macedonian nobles, which he named the 'hetairoi' (or Companion]! cavalry, and an infantry body drawn from the commoners and trained to fight in phalangite formation: these he called the »pezetairoi» (or foot-companions). Philip II (359-336 B.C.) expanded the kingdom and greatly increased the manpower resources for war. Towards the end of his reign he started preparations for the invasion of the Persian empire and levied many more Macedonians than had hitherto been involved in the king's wars. In order to attach these men more closely to himself he extended the meaning of the terms »hetairol» and 'pezetairoi to refer to the whole bodies of Macedonian cavalry and heavy infantry which served under him on his campaigning. -

Bulletin of Ancient Macedonian Studies 2020

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Departament de Ciències de l’Antiguitat i l’Edat Mitjana Karanos BULLETIN OF ANCIENT MACEDONIAN STUDIES http://revistes.uab.cat/karanos 03 ), online ( 3521 - 2604 ISSN e 2020 (paper), 6199 - 2604 , ISSN 20 20 , 3 Vol. Karanos Bulletin of Ancient Macedonian Studies Vol. 3 (2020) President of Honor Secretary F. J. Gómez Espelosín, Marc Mendoza Sanahuja (Universitat Autònoma (Universidad de Alcalá) de Barcelona) Director Edition Borja Antela-Bernárdez, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Departament de Ciències de l’Antiguitat i l’Edat Mitjana Editorial Board 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona). Spain Borja Antela-Bernárdez Tel.: 93 581 47 87. Antonio Ignacio Molina Marín Fax: 93 581 31 14 (Universidad de Alcalá) [email protected] Mario Agudo Villanueva http://revistes.uab.cat/karanos (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) Layout: Borja Antela-Bernárdez Advisory Board F. Landucci (Università Cattolica del Printing Sacro Cuore) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona E. Carney (Clemson University) Servei de Publicacions D. Mirón (Universidad de Granada) 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona). Spain C. Rosillo (Universidad Pablo de Olavide) [email protected] F. Pownall (University of Alberta) http://publicacions.uab.cat/ W. L. Adams (University of Utah) N. Akamatis (International Hellenic University) ISSN: 2604-6199 (paper) V. Alonso-Troncoso (Universidad de A Coruña) eISSN 2604-3521 (online) A. Domínguez Monedero (Universidad Dipòsit legal: B 26.673-2018 Autónoma de Madrid) F. J. Gómez Espelosín (Universidad de Alcalá) Printed in Spain W. S. Greenwalt (Santa Clara University) Printed in Ecologic paper M. Hatzopoulos (National Hellenic Research Foundation) S. Müller (Philipps-Universität Marburg) M. Jan Olbrycht (University of Rzeszów) O. -

Alexander the Great's Cabinet

Letter from Academic Assistant I would like to start by welcoming you all to this annual session of HaydarpaşaMUN! I also would like to state that I think you are the twelve luckiest delegates of the conference since you are now allocated in our traditional World-Changing Commander’s Cabinet themed committee. In this year’s cabinet you will represent the bravest and the most sharp witted of the soldiers since you will be serving Alexander III of the Macedons as known as Alexander the Great and shall have the most adventurous battles devoted to his army. On the other hand you will further learn upon the history’s biggest mastermind and be granted the chance to rewrite it. I can guarantee you that you will have the most of fun and also the biggest academic pleasure. Therefore I would like to thank every person behind this conference by starting with our passionate and sympathetic Secretary General Zeynep Naz Coşkun and our esteemed and hardworking Crisis Team since they are the ones who will be providing you this highly prestigious committee before concluding my thanks I would also like to thank my academic trainee Zeynep Erşen for her hardworks and fellow companionship In order to conclude I can recommend you nothing but further research the topic since ancient warfare ,political structure and relations can be really hard to understand. I personally recommend the website called ancient history encyclopedia also the videos that briefly explains warfare of the era since visual explanations are more easy to understand. In case you have any questions please don’t hesitate to contact me and my trainee via m [email protected] and z[email protected] Hope to see you soon! Yağmur Zühal Tokur - Academic Assistant Zeynep Erşen - Academic Trainee Introduction Alexander the Great whom you will become companies of for these four days was not just the king of Macedonia or the leader that started Hellenistic Era. -

Joseph Roisman

-j I a Joseph Roisman ALEXANDER S VETERANS AND THE EARLY WARS OF THE SUCCESSORS JN 71019 The Fordyce W. Mitchel Memorial Lecture Se ries, sponsored by the Department of History at the University of Missouri-Columbia, began in October 2000. Fordyce Mitchel was Professor of Greek History at the University of Missouri Columbia until his death in 1986. In addition to his work on fourth-century Greek history and epigraphy, including his much-cited Lykourgan Athens: 338-322, Semple Lectures 2 (Cincinnati, 1970), Mitchel helped to elevate the ancient his tory program in the Department of History and to build the extensive library resources in that field. The lecture series was made possible by a generous endowment from his widow, Mrs. Marguerite Mitchel. It provides for a biennial series of lectures on original aspects of Greek history and society, given by a scholar of high international standing. The lectures are then revised and arc currently published by the University of Texas Press. PREVIOUS MITCHEL PUBLICATIONS: Carol G. Thomas, Finding People in Early Greece (University of Missouri Press, 2005) Mogens Herman Hansen, The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City-State Culture (University of Missouri Press, 2006) Mark Golden, Greek Sport and Social Status (University of Texas Press, 2008) ALEXANDER S VETERANS AND THE EARLY WARS OF THE SUCCESSORS by Joseph Roisman JLCU1 0 5203 dve UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS, AUSTIN Copyright 2012 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2012 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. -

Inloop Document Talanta 12-02-2015 20:35 Pagina 51

pag 51-68:inloop document Talanta 12-02-2015 20:35 Pagina 51 TALANTA XLII - XLIII (2010-2011), 51-67 ALEXANDER’S THESSALIAN CAVALRY Rolf Strootman This paper examines the organization, numbers and tactics of the Thessalian cav - alry unit in the army of Alexander the Great. It is argued that already Philip II recognized the importance of Thessaly as a recruiting ground for heavy (noble) cavalry with regard to his planned invasion of Asia, and that it was partly for this reason that Philip closely integrated Thessaly in the Argead imperial system, cul - tivating personal relations with the Thessalian noble families also as a counter - weight to the power of the traditional Macedonian noble cavalry, the hetairoi (Companions). Alexander inherited these arrangements. The Thessalians on their part joined Alexander’s expedition more enthusiastically than other Greeks because of these pre-existing bonds with the Macedonian royal family and because the promise of honor and booty agreed with the heroic mentality of the Thessalian aristocracy. Introduction Various non-Macedonian troops accompanied Alexander the Great to Asia in 334 BC 1. Among these, the contingent of Thessalian horsemen stands out. First, because Thessalians constituted by far the largest Greek unit in Alexander’s army. Second, because unlike other Greek troops the Thessalians fought in the great battles at the Granicus, at Issus and at Gaugamela. And not only did they participate actively in these battles, they were given important tactical responsi - bilities and played a crucial role on the battlefield, where invariably their task was to defend the left flank against the Persian cavalry. -

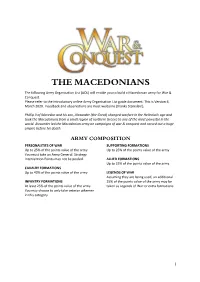

THE MACEDONIANS the Following Army Organisation List (AOL) Will Enable You to Build a Macedonian Army for War & Conquest

THE MACEDONIANS The following Army Organisation List (AOL) will enable you to build a Macedonian army for War & Conquest. Please refer to the introductory online Army Organisation List guide document. This is Version 6, March 2020. Feedback and observations are most welcome (thanks Stanislav!). Phillip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander (the Great) changed warfare in the Hellenistic age and took the Macedonians from a small region of northern Greece to one of the most powerful in the world. Alexander led the Macedonian army on campaigns of war & conquest and carved out a huge empire before his death. ARMY COMPOSITION PERSONALITIES OF WAR SUPPORTING FORMATIONS Up to 25% of the points value of the army Up to 25% of the points value of the army You must take an Army General. Strategy Intervention Points may not be pooled. ALLIED FORMATIONS Up to 25% of the points value of the army. CAVALRY FORMATIONS Up to 40% of the points value of the army. LEGENDS OF WAR Assuming they are being used, an additional INFANTRY FORMATIONS 25% of the points value of the army may be At least 25% of the points value of the army. taken as Legends of War or extra formations. You may choose to only take veteran pikemen in this category. 1 PERSONALITIES OF WAR PHILLIP OF MACEDON Mo L S Abilities SIPS ZOC Pts 9 3 +2 Army 2 15'' 190 General Equipment: As unit Formation: Personality Armour Value: As unit May move independently and has an Armour Options: May add up to 2 additional Strategy Value of 3. -

Macedonian Cavalry

Durham E-Theses The army of Alexander the great English, Stephen How to cite: English, Stephen (2002) The army of Alexander the great, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4162/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The Army of Alexander the Great Stephen English The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for degree of M.A Department of Classics and Ancient History University of Durham 2002 0 MAY 2003 J2oox( Stephen English The Army of Alexander the Great Submitted for degree of M. A. Department of Classics, University of Durham 2002 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to be an examination of the army of Alexander the Great, concentrating upon questions of organization and equipment. -

0916E5e0-343F-46F5-89B8-1611477166B1.Pdf

THE HORSEMEN OF ATHENS PUBLISHED FOR THE CENTER FOR HELLENIC STUDIES GLENN RICHARD BUGH The Horsemen of Athens PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY Copyright © 1988 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, NewJersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Guildford, Surrey ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bugh, Glenn Richard, 1948- The horsemen of Athens / Glenn Richard Bugh. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN 0—691—05530-0 (alk. paper) : i. Cavalry—Greece—Athens—History. 2. Athens (Greece)— History, Military. I. Title. U33.B84 1988 357'.!'09385—dci9 88-3210 Publication of this book has been aided by the Whitney Darrow Fund of Princeton University Press This book has been composed in Linotron Sabon Clothbound editions of Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Paperbacks, although satisfactory for personal collections, are not usually suitable for library rebinding Printed in the United States of America by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX INTRODUCTION xi ABBREVIATIONS XV 1. Aristocratic Horsemen of Archaic Athens 3 2. Cavalry of Empire 39 3. The Peloponnesian War 79 4. The Year of the Thirty Tyrants 120 5. The Athenian Cavalry in the Age of Philip of Macedon 154 6. The Horsemen of Hellenistic Athens 184 APPENDIXES 207 Appendix A: Ages of the Horsemen of the Pythais 207 Appendix B: The Hipparch to Lemnos 209 Appendix C: The Hipparcheion 219 Appendix D: Hippotoxotai and Prodromoi 221 CATALOGUS HIPPEUM 225 INDEX 263 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS (,following page z6z) FIGURE I. -

Nicholas Victor Sekunda

FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXII, PL ISSN 0860-0007 NICHOLAS VICTOR SEKUNDA HARE-HUNTING AND CAVALRY TACTICS1 It seems to have been Jacoby (FGrH 328 F 71) who first established that hamippoi were a type of Greek infantry trained to operate alongside cavalry, as the very name indicates: for it literally means 'together with the cavalry'. Jacoby thought the hamippoi to have been a Boeotian speciality. In fact the first reference to the employment of troops of this type seems to be in Herodotus (7.158) who mentions that in the army of Gelon the tyrant of Syracuse there were 2,000 cavalry accompanied by an equal number of hippodromoi psiloi or 'psiloi who run alongside the cavalry'. Psiloi is the normal Greek word used for light infantry. The context of this passage is the events of 480 ВС, leading up to the Persian invasion, which gives us a terminus ante quern for the establishment of infantry of this type in Greek armies. It is, indeed possible that Gelon himself was responsible for raising a unit of such troops for the first time. It is a well-known fact that in Greek history military innovations were most frequently implemented by totalitar- ian governments who had the adequate financial resources available to implement reform. However the uneven and gen- erally poor quality of the evidence for Greek history before the Persian wars does not allow us to reach a firm conclusion on this matter. Jacoby had restricted himself to the literary evidence alone, and I believe I was the first to identify hamippoi in the representational evidence, in Nick Sekunda, colour plates by Angus McBride, The Greeks. -

Alexander's Thessalian Cavalry

ALEXANDER’S THESSALIAN CAVALRY Rolf Strootman This paper examines the organization, numbers and tactics of the Thessalian cavalry unit in the army of Alexander the Great. It is argued that already Philip II recognized the importance of Thessaly as a recruiting ground for heavy (noble) cavalry with regard to his planned invasion of Asia, and that it was partly for this reason that Philip closely integrated Thessaly in the Argead imperial system, cultivating personal relations with the Thessalian noble families also as a counterweight to the power of the traditional Macedonian noble cavalry, the hetairoi (Companions). Alexander inherited these arrangements. The Thessalians on their part joined Alexander’s expedition more enthusiastically than other Greeks because of these pre-existing bonds with the Macedonian royal family and because the promise of honor and booty agreed with the heroic mentality of the Thessalian aristocracy. Introduction Various non-Macedonian troops accompanied Alexander the Great to Asia in 334 BC 1. Among these, the contingent of Thessalian horsemen stands out. First, because Thessalians constituted by far the largest Greek unit in Alexander’s army. Second, because unlike other Greek troops the Thessalians fought in the great battles at the Granicus, at Issus and at Gaugamela. And not only did they participate actively in these battles, they were given important tactical responsibilities and played a crucial role on the battlefield, where invariably their task was to defend the left flank against the Persian cavalry. Although the king’s army was formally a pan-Hellenic force, in practice it was a largely Macedonian army and the token units that had been sent by the southern Greek poleis in accordance with the obligations of the League of Corinth – predominantly 1 All dates are BC unless otherwise indicated. -

Alexander the Great: Lessons in Strategy

Alexander the Great This book offers a strategic analysis of one of the most outstanding military careers in history, identifying the most pertinent strategic lessons from the cam- paigns of Alexander the Great. David Lonsdale argues that since the core principles of strategy are eternal, the study and analysis of historical examples have value to the modern theorist and practitioner. Furthermore, as strategy is so complex and challenging, the remarkable career of Alexander provides the ideal opportunity to understand best practice in strategy, as he achieved outstanding and continuous success across the spectrum of warfare, in a variety of circumstances and environments. This book presents the thirteen most pertinent lessons that can be learned from his campaigns, dividing them into three categories: grand strategy, military operations, and use of force. Each of these categories provides lessons pertinent to the modern strategic environment. Ultimately, however, the book argues that the dominant factor in his success was Alexander himself, and that it was his own characteristics as a strategist that allowed him to overcome the complexities of strategy and achieve his expansive goals. This book will be of great interest to students of Strategic Studies, Military History and Ancient History. David J. Lonsdale is Lecturer in Strategic Studies at the University of Hull. He is author of two previous books. Strategy and history Series editors: Colin Gray and Williamson Murray This new series will focus on the theory and practice of strategy. Following Clausewitz, strategy has been understood to mean the use made of force, and the threat of the use of force, for the ends of policy.