One Teacher's Search for Meaning in the Classroom A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Junk Feminism and Nuclear Wannabes

SAARA SÄRMÄ Junk Feminism and Nuclear Wannabes Collaging Parodies of Iran and North Korea ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of the School of Management of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Auditorium Pinni B 1100 of the University, Kanslerinrinne 1, Tampere, on September 5th, 2014, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE SAARA SÄRMÄ Junk Feminism and Nuclear Wannabes Collaging Parodies of Iran and North Korea Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1961 Tampere University Press Tampere 2014 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION School of Management Finland Copyright ©2014 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1961 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1446 ISBN 978-951-44-9534-2 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9535-9 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2014 Painotuote Acknowledgements The journey that has led to completion of this doctoral dissertation has been a long one. Along the way, many people have helped me, knowingly and unknowingly, to walk unafraid. One of this work’s many points of origins was in the fall of 1998 when I started my undergrad degree in Tampere. At the intro course, Osmo Apunen drew upper case IR and lower case i.r. onto the blackboard and I struggled to understand the difference. Little did I know how significant those two pairs of letters and their relationship would become in my life. I sincerely hope this dissertation does justice to the old Tampere school of IR! From the bottom of my heart, I would like to thank the two pre-examiners Christine Sylvester and Julian Reid, who approved this dissertation for publication, and Marysia Zalewski, who agreed to be my opponent at the public defense. -

Exploring Joy and Learning in Low-Income Schools Using Design-Thinking Strategies

Joel M. Croichy Exploring Joy and Learning in Low-Income Schools using Design-Thinking Strategies. M.F.A. Department of Design Thinking, 2019 Radford University I ii ABSTRACT: This study explored joy and learning in low-income schools using design-thinking strategies. The researcher gathered 29 individuals consisting of teachers, former students, parents of former students, administrators, counselors, and church members who come from and work in low-income schools. The researcher conducted a 10-minute activity with children ages 7-10, who attend Sunday school, where they created collages of images that showcased what brings them joy in general. In addition, two individuals who previously attended low-incomes schools journaled their experiences. Upon completion of the Sunday school activity and journaling, two workshops were conducted. The first workshop involved three design-thinking methods: rose, thorn, bud, affinity clustering and statement starters. The intention of these workshops was to identify patterns, positives, negatives, and possibilities associated with student learning and joy in low-income schools. The second workshop consisted of two design-thinking methods: round robin and visualize the vote, where participants shared ideas and passed them along until an unconventional solution was found. Results indicated that building a sense of safety in school and mental toughness by overcoming adversity could help provide joy, while poor conditions (lack of technology, gangs) in low-income schools leads to higher dropout rates. While eight patterns emerged from the affinity clustering exercise (e.g., positive communities, poor building conditions, lack of financial support, etc.), participants focused on creating stability in schools as the most important feature. -

Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21St Century

Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21st Century Volume 1: Literature Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21st Century Volume 1: Literature Edited by Monika Coghen Zygmunt Mazur Beata Piątek Jagiellonian University Press The publication of this volume was supported by the Faculty of Philology of the Jagiellonian University, and the Institute of English Philology, Jagiellonian University. BOARD OF REVIEWERS Teresa Bela Joelle Biele Julie Campbell Benjamin Colbert Marta Gibińska-Marzec Aleksandra Kędzierska David Malcolm Irena Przemęcka Krystyna Stamirowska-Sokołowska Lisa Vargo Anna Walczuk COVER DESIGN Marcin Klag TYPESETTING Sebastian Leśniewski TECHNICAL EDITOR Mirosław Ruszkiewicz © Copyright by Monika Coghen, Zygmunt Mazur, Beata Piątek & Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego First edition, Kraków 2010 No part of this book may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher. ISBN 978-83-233-3117-9 I WYDAWNICTWO] UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO www.wuj.pl Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Redakcja: ul. Michałowskiego 9/2, 31-126 Kraków tel. 12-631-18-81, 12-631-18-82, fax 12-631-18-83 Dystrybucja: tel. 12-631-01-97, tel./fax 12-631-01-98 tel. kom. 0506-006-674, e-mail: [email protected] Konto: PEKAO SA, nr 80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 A Bibl. Jagiell. ■ Contents Preface................................................................................................................................... 9 ELINOR SHAFFER Seven Times Seven Types of Ambiguity: William Empson and Twentieth-Century Criticism....................................................................................... 11 ROBERT REHDER Meaning and Change of Form: Eliot, Pound and Niedecker............................................ -

Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde

Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to npg - PalgraveConnect - 2013-09-11 - licensed to npg PalgraveConnect www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137276865 - Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde, Arndt Niebisch Avant-Gardes in Performance Series Editors Sarah Bay-Cheng, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Martin Harries, University of California, Irvine Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde: On the Abuse of Technology and Communication By Arndt Niebisch Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to npg - PalgraveConnect - 2013-09-11 - licensed to npg PalgraveConnect www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137276865 - Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde, Arndt Niebisch Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde On the Abuse of Technology and Communication Arndt Niebisch Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to npg - PalgraveConnect - 2013-09-11 - licensed to npg PalgraveConnect www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137276865 - Media Parasites in the Early Avant-Garde, Arndt Niebisch media parasites in the early avant-garde Copyright © Arndt Niebisch, 2012. All rights reserved. First published in 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the World, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. -

Deconstructing Bentham's Panopticon

tripleC 9(1): 62-76, 2011 ISSN 1726-670X http://www.triple-c.at Deconstructing Bentham’s Panopticon: The New Meta- phors of Surveillance in the Web 2.0 Environment Manuela Farinosi Department of Human Sciences - University of Udine, Italy [email protected] Abstract: This article reflects on the meaning of the words “control” and “privacy” in light of the intensive diffusion of user generated content on the web. It presents some results of an empirical research based on 145 essays written by Italian students. The data were analysed from a qualitative point of view to understand how young people frame the topic of control on the web 2.0. The attention is focused on the metaphors used to describe online platforms and on the social environments they mention when they speak about the impacts of online diffusion of personal content on offline life. The results show that the new control practices cannot be adequately described within the classical framework of vertical control. The traditional panoptic principle of observation has to a certain extent been transformed and the Panopticon itself is no more an effective metaphor to describe the control dynamics on the web 2.0. Keywords: Social Media, Metaphors, Surveillance, Control, Panopticon, Privacy, Social Network Sites, Web 2.0, User Generated Content Acknowledgement: This paper was presented in the conference track “Surveillance in society“ (convenors: Anders Al- brechtslund, Kees Boersma, Christian Fuchs, Peter Lauritsen), 2010 Conference of the European Association for the Stud- ies of Science and Technology (EASST), University of Trento, Italy. September 2-4, 2010. 1. -

A Self-Study of the Intersections of Curriculum, Practice, and Identity

Kutztown University Research Commons at Kutztown University Education Doctorate Dissertations Education Spring 3-26-2020 Making the Journey Personal: A Self-Study of the Intersections of Curriculum, Practice, and Identity Patricia J. Tinsman-Schaffer Kutztown University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/edddissertations Part of the Art Education Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Tinsman-Schaffer, Patricia J., "Making the Journey Personal: A Self-Study of the Intersections of Curriculum, Practice, and Identity" (2020). Education Doctorate Dissertations. 3. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/edddissertations/3 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Education at Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctorate Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: MAKING THE JOURNEY PERSONAL Making the Journey Personal: A Self-Study of the Intersections of Curriculum, Practice, and Identity A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Education Doctorate in Transformational Teaching and Learning Program of Kutztown University of Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Education Doctorate By Patricia Tinsman-Schaffer 26 March 2020 MAKING THE JOURNEY PERSONAL: A SELF-STUDY ii ©2020 Patricia Tinsman-Schaffer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Etta's Cafe and Holmes Carvery to Close with Opening of New Eatery

The independent newspaper of Washington University in St. Louis since 1878 VOLUME 140, NO. 11 MONDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2018 WWW.STUDLIFE.COM OVERTIME DRAMA HIPPO CAMPUS INDIE MAGIC No. 1 women’s Minnesota band Laura Stevenson soccer triumphs evolves sonically and others energize over Emory in to- and emotionally on Gargoyle crowd in the-wire thriller new album ‘Bambi’ KWUR show (Sports pg 6) (Cadenza, pg 9) (Cadenza, pg 10) OLYMPIC LEGACY Etta’s Cafe and Holmes RINGS CELEBRATING 1904 GAMES UNVEILED carvery to close with opening of new eatery CURRAN NEENAN other locations at the University. CONTRIBUTING REPORTER “If Holmes Lounge closes, there will absolutely be work for Etta’s Cafe and the carvery sta- the good people at the carvery tion in Holmes Lounge are both elsewhere on campus, most likely tentatively set to close with the at Parkside,” Kuebler said. opening of Parkside Cafe, an The University is exploring dif- eatery in the newly constructed ferent options for how to utilize Schnuck’s Pavilion, in the sum- the space the carvery currently mer of 2019. occupies, including transitioning Parkside Cafe will have seating the carvery into a coffee shop. for over 250 patrons and operate “It probably will continue to be from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on a place for coffee and those kinds weekdays. It will feature a rotat- of things if you’re going to study. ing menu, including a grill and It’s a beautiful place and we’re classic St. Louis foods like toasted contemplating what to do to make ravioli and St. -

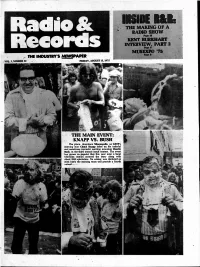

The Main Event: Knapp Vs

THE MAKING OF 1a, Radio Sr. RADIO SHO Page 10 KENT BURK INTERVIE W, PART 2 Records Page 8 MUSEXPO '7 Page 8 _ THE INDUSTRY'S NEWSPAPER VOL. 3, NUMBER 32 FRIDAY, AUGUST 15, 1975 THE MAIN EVENT: KNAPP VS. BUSH The place, downtown Minneapolis, as KSTP's morning man Chuck Knapp takes on his colorful and sometimes sarcastic morning newsman Charlie Bush. in the third annual insult contest. The event has grown so popular that this year even a local television station covered the story along with about 2000 spectators. No winner was declared so most likely the morning team will provide a fourth annual Michael Murphey's fantastic success is documented by his gold single,"Wildfire." So it's no surprise that immediately after its release, "Carolina in the Pines" 50131 is receiving heavy telephones, across-the-board airplay, and a Gavin Personal Pick. "Carolina in the Pines" Michael Murphey's sizzling follow-up to "Wildfire :A .50084 And there are eight more just like them, on Michael's "Blue Sky- Night Thu,rnIACalbum. On Epic Records - e W ORCA RIG 01975 .0 rsonat Management byJerryWeintraub, Management Three, Ltd., 400 South Beverly Drive,Beverly Hills, Cal ifomia 90212(213) 277-9633 Also available on tape. Page 3 RADIO & RECORDS R&R/Friday. August 15, 1975 RADIO GIVES RADIO NEWS AWAY how long the station's jocks STAR TREK that August is the month of Philadelphia is hosting the tan. So, they're giving away a could ride the cycle on a certain amount of gas. -Star Trek" convention for tan, obtainable in Hawaii. -

Grotesque Corporeality: Queering the Bulge in Gay Male Underwear

Grotesque Corporeality: Queering the Bulge in Gay Male Underwear by Joshua Nathaniel Williams BDes, Ryerson University, 2011 BA, Northern Kentucky University, 2004 A MRP presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Fashion Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Joshua Nathaniel Williams, 2018 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A MRP I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This creative Major Research Project (MRP) uses a practice-led research method approach to investigate a correlation between the queer body and the grotesque. The research questions attempt to explore the way queer bodies are used to transgress and subvert both heteronormative and homonormative ideologies and masculinities using grotesque humour. This project also examines the relationship between fashion and the body to resist normative values and ideals. Artistic practices combine to create a volume of work consisting of collage, underwear garments, and photographs. These creative outputs are then analyzed and discussed with a focus on Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories of the grotesque and carnivalesque, Gilles Deleuze’s theory of the Body without Organs, and queer theory. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ring around The Rose Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7426863k Author Ferrell, Elizabeth Allison Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ring around The Rose: Jay DeFeo and her Circle By Elizabeth Allison Ferrell A dissertation submitted for partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus Timothy Clark Professor Shannon Jackson Professor Darcy Grigsby Fall 2012 Copyright © Elizabeth Allison Ferrell 2012 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Ring around The Rose by Elizabeth Allison Ferrell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair From 1958 to 1966, the San Francisco artist Jay DeFeo (1929-89) worked on one artwork almost exclusively – a monumental oil-on-canvas painting titled The Rose. The painting’s protracted production isolated DeFeo from the mainstream art world and encouraged contemporaries to cast her as Romanticism’s lonely genius. However, during its creation, The Rose also served as an important matrix for collaboration among artists in DeFeo’s bohemian community. Her neighbors – such as Wallace Berman (1926-76) and Bruce Conner (1933-2008) – appropriated the painting in their works, blurring the boundaries of individual authorship and blending production and reception into a single process of exchange. I argue that these simultaneously creative and social interactions opened up the autonomous artwork, cloistered studio, and the concept of the individualistic artist championed in Cold-War America to negotiate more complex relationships between the individual and the collective. -

Encyclopedia of Media and Communication

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION The first comprehensive encyclopedia for the growing fields of media and communication studies, the Encyclopedia of Media and Communication is an essential resource for beginners and seasoned academics alike. Contributions from over fifty experts and practitioners pro- vide an accessible introduction to these disciplines’ most important concepts, figures, and schools of thought – from Jean Baudrillard to Tim Berners-Lee, and podcasting to Peircean semiotics. Detailed and up to date, the Encyclopedia of Media and Communication synthesizes a wide array of works and perspectives on the making of meaning. The appendix includes time- lines covering the historical record for each medium, from either antiquity or their inception to the present day. Each entry also features a bibliography linking readers to relevant re- sources for further reading. The most coherent treatment yet of these fields, the Encyclopedia of Media and Communication promises to be the standard reference text for the next genera- tion of media and communication students and scholars. marcel danesi is the director of and a professor in the Program in Semiotics and Commu- nication Theory at Victoria College, University of Toronto. Editor Marcel Danesi Advisory Editors Paul Cobley Derrick De Kherckhove Umberto Eco Eddo Rigotti Janet Staiger Encyclopedia of Media and Communication Edited by Marcel Danesi UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2013 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-4426-4314-7 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-4426-1169-6 (paper) Printed on acid-free paper Toronto Studies in Semiotics and Communication Editors: Marcel Danesi, Umberto Eco, Paul Perron, Peter Schultz, and Roland Posner Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Encyclopedia of media and communication / edited by Marcel Danesi. -

Blim Dissertation Revisions Draft 2

Patchwork Nation: Collage, Music, and American Identity by Richard Daniel Blim A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Mark Clague, Co-Chair Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paul A. Anderson Professor Steven M. Whiting Acknowledgements This dissertation has benefited from what I can only describe as a collage of voices of support and wisdom throughout the process. I wish to acknowledge the financial support of the Rackham Graduate School; The University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance; and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I owe a great deal to my committee for their insight and guidance from the beginning. Steven Whiting helped sharpen my theoretical approach and navigate various definitions. Paul Anderson’s comments always cut right to the heart of whatever issue of question was most daunting and pointed me in the right division, helping me to tell, as he often suggested, a bigger story. It has been my fortune to find two co-chairs who work so well together. Mark Clague and Charles Hiroshi Garrett have encouraged my interdisciplinary interests throughout my time at the University of Michigan. For the dissertation, they have pushed me to become a better scholar and writer, patiently reading sprawling drafts and helping to wrangle my ideas into shape, and tactfully impelling me to pursue bigger and bigger questions with more and more clarity and nuance. In particular, I am deeply appreciative of Mark’s energizing and provocative pep talks and willingness to entertain any question no matter how tangential it might have seen, and of Chuck’s impeccable and thoughtful comments on everything I submitted, returned with superhuman speed, and his dissertation whisperer-like ability to get me to make the inevitable cuts.