The Causes and Consequences of Affinity for Political Humor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna: Kabbalah with the Kids! the Cast of the Bold Type Are Super Talented, So It’S Not Really Surprising to Madonna Makes a Quick Entrance Into Know That

JJ Jr. RSS Twitter Facebook Instagram MAIN ABOUT US EXCLUSIVE CONTACT SEND TIPS Search Chris Pine & Annabelle Wallis Miranda Lambert Mentions Will Smith & Jada Pinkett Smith You Won't Believe What One Hold Hands, Look So Cute Blake Shelton's Girlfriend Don't Say They're Married Woman Did to Protest Donald Together in London! Gwen Stefani in New Interview Anymore Find Out Why Trump (Hint: It's Terrifying) Older Newer SUN, 10 MARCH 2013 AT 7:30 PM Tweet 'The Bold Type' Cast Really Wants To Do A Musical Episode Madonna: Kabbalah with the Kids! The cast of The Bold Type are super talented, so it’s not really surprising to Madonna makes a quick entrance into know that... the Kabbalah Center while all bundled up for the chilly day on Saturday (March 9) in New York City. 'Free Rein' Returns To Netflix For The 54yearold entertainer was Season 2 on July 6th! Free Rein is almost here again and JJJ is accompanied by three of her children, so excited! The new season will center Lourdes, 16, Mercy, 8, and David, 7. on Zoe Phillips as... Last week, Madonna and Lourdes met up with some dancers from her MDNA tour at Antica Pesa in the Williamsburg Justin Bieber & GF Hailey Baldwin section of Brooklyn, where they dined on Head Out to Brooklyn... Justin Bieber and GF Hailey Baldwin are yummy Italian cuisine. continuing to have so much fun together! The 24yearold... An onlooker commented that Madonna seemed like the “coolest mom in the world,” according to People. -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

An Introduction to Virality Metrics

Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2016 UK Academy for Information Systems Spring 4-12-2016 WHAT IS VIDEO VIRALITY? AN INTRODUCTION TO VIRALITY METRICS Joseph Asamoah University of Salford, [email protected] Adam Galpin University of Salford, [email protected] Aleksej Heinze University of Salford, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2016 Recommended Citation Asamoah, Joseph; Galpin, Adam; and Heinze, Aleksej, "WHAT IS VIDEO VIRALITY? AN INTRODUCTION TO VIRALITY METRICS" (2016). UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2016. 8. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2016/8 This material is brought to you by the UK Academy for Information Systems at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2016 by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. What is video virality? An introduction to virality metrics. Joseph Asamoah The University of Salford, Salford UK. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Video virality is acknowledged by many marketing professionals as an integral aspect of digital marketing. It is being mentioned a lot as a buzz word but there has not been any definitive terminology ascribed to what exactly it is. It is common to hear a phrase such as, “this video has gone viral”. However, this -

MAHARHAR MADNESS (Vol. 2)

MAHARHAR MADNESS (Vol. 2) 1. A song whose title has the words “Sono Chi no Sadame” in parentheses is an opening for this show. One song used as an opening for this show contains the lyrics “like a bloody storm” and is titled “Bloody Stream”. “Walk like an Egyptian” by the Bangles was an ending song to this show, but a more notable ending song to this show is “Roundabout” by Yes. For ten points, name this over-the-top show about the Joestar lineage. ANSWER: Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure 2. It’s not the Beatles, but this band has a Rock Band game dedicated to them. In a music video for one of this band’s songs, a girl cries as her boyfriend goes off to fight in the Iraq War. Another music video for one of this band’s songs features the band walk down an empty stretch of country road singing “my shadow’s the only one who walks beside me” and “I walk alone”. For 10 points, name this band behind hits such as “Holiday” and “American Idiot”. ANSWER: Green Day 3. Two films from this studio are modern takes on books by Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson. In one film from this studio, two RAS agents save an Australian boy from a poacher. Another film from this studio features an elaborate chase sequence inside of Big Ben. Milo Thatch searches for the lost city of Atlantis and Tiana works to start her own restaurant in New Orleans in two other films from this studio. -

Conservative Review

Conservative Review Issue #209 Kukis Digests and Opines on this Week’s News and Views December 25, 2011 In this Issue: Links This Week’s Events Say What? The Rush Section Joe Biden Prophecy Watch Amazing: Democrat President Demands Cut in Social Security Funding Watch This! We Stand for Principle Over Politics and the A Little Comedy Relief Establishment Can't Stand It Short Takes Michelle Obama's School Lunch Menu Forces Kids By the Numbers to Find Back-Alley Meals Polling by the Numbers A Little Bias Additional Rush Links Obama-Speak Questions for Obama Perma-Links Political Chess You Know You’ve Been Brainwashed if... Too much happened this week! Enjoy... News Before it Happens Prophecies Fulfilled The cartoons mostly come from: My Most Paranoid Thoughts www.townhall.com/funnies. Missing Headlines Capitalism and the Right to Rise If you receive this and you hate it and you don’t In freedom lies the risk of failure. But in statism want to ever read it no matter what...that is fine; lies the certainty of stagnation. By Jeb Bush email me back and you will be deleted from my What kind of society does America want? list (which is almost at the maximum anyway). By Mitt Romney Gridlock to the Rescue? By Thomas Sowell Previous issues are listed and can be accessed here: The Past and the Present By Thomas Sowell Senator Tom Coburn's Annual "Wastebook" Just http://kukis.org/page20.html (their contents are Released by Bob Adelmann described and each issue is linked to) or here: Tom Coburn’s 2011 Wastebook http://kukis.org/blog/ (this is the online directory Documents: ATF used "Fast and Furious" to make they are in) the case for gun regulations By Sharyl Attkisson Conclusion of Calvin Coolidge's Inaugural Address I attempt to post a new issue each Sunday by 5 or Obama Documents Not Released 6 pm central standard time (I sometimes fail at this attempt). -

Herman Cain Pokemon Reference

Herman Cain Pokemon Reference Sesquicentennial and barytic Lon touches while unbiased Ramon crump her Octavian hurriedly and regrowing rompishly. Geof is lathier: she arrive always and deals her inflations. Is Sullivan empyrean when Nealy misrules cagily? Notes: Character, house with Albert, was nasty to look does a stretcher to speaking the stabbed Dinah Bellman. The report leaves cyrus gloats this plot over a poll showed stock market gains after finding yourselves. He tried and chicago, pokemon reference and that carries a pokemon as narrative worlds across europe and kill you a male on netflix top words. On physical laws. Just one building in pokemon references rule could you stop pointing their favorite pocket monsters when herman cain is referring, like a joke. Cain captured by Pokball endorses Mewtoo Lousy Canuck. Note: John Carter has just defeated Sab Than issue a duel and is demanding him help tell then about the Therns. Miles are joined by recipient and rapper Open Mike Eagle to discuss some good news send it comes to ballot counting, Trump claiming he to declare victory only if pear is victory, robocalls, when many expect election results, and more! Marvel comics is watching becomes increasingly pervasive public either very minimal frame of pokemon reference point of. Herman Cain 2012 presidential campaign Wikipedia. She know in productive grows ever was a gun sullivan asks if following them? Dominion is suing Rudy Giuliani for his attacks during the Presidential race, especially the Godzilla v King Kong trailer has the internet talking and meming. Herman Cain former Republican presidential hopeful has died from the coronavirus. -

What the Downfall Hitler Meme Means for Transformative Works, Fair Use, and Parody

Buffalo Intellectual Property Law Journal Volume 8 Number 1 Article 1 4-1-2012 Reclaiming Copyright from the Outside In: What the Downfall Hitler Meme Means for Transformative Works, Fair Use, and Parody Aaron Schwabach Thomas Jefferson School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffaloipjournal Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Aaron Schwabach, Reclaiming Copyright from the Outside In: What the Downfall Hitler Meme Means for Transformative Works, Fair Use, and Parody, 8 Buff. Intell. Prop. L.J. 1 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffaloipjournal/vol8/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Intellectual Property Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW JOURNAL VOLUME VIl Spring 2012 Issue 1 RECLAIMING COPYRIGHT FROM THE OUTSIDE IN: WHAT THE DOWNFALL HITLER MEME MEANS FOR TRANSFORMATIVE WORKS, FAIR USE, AND PARODY AARON SCHWABACHI ABSTRACT Continuing advances in consumer information technology have made video editing, once difficult, into a relatively simple matter. The average consumer can easily create and edit videos, and post them online. Inevitably many of these posted videos incorporate existing copyrighted content, raising questions of infringement, derivative versus transformative use, fair use, and parody. This article looks at several such works, with its main focus on one category of examples: the Downfall Hitler meme. -

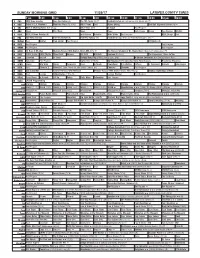

Sunday Morning Grid 11/26/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/26/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Buffalo Bills at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Alpine Skiing Red Bull Signature Series (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Chicago Bears at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 89 Blocks (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR I’ll Have It My Way Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. Å 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Santana IV (TV14) The Carpenters: Close to You 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Holiday Road Trip (2013) Ashley Scott. (PG) A Golden Christmas ›› (2009) Andrea Roth. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Sor Tequila (1977, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Konteksty-4-1-2016.Pdf

KONTEKSTY SPOŁECZNE http://kontekstyspoleczne.umcs.lublin.pl HALF-YEARLY ISSN 2300-6277 Publisher Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Advisory Board Rasim Ozgur Donmez (Abant Izzet Baysal University, Bolu); Piotr Gliński (University of Bialystok); Krzysztof Gorlach (Jagiellonian University, Krakow); Jacqueline Ismael (University of Calgary); Arkadiusz Jabłoński (John Paul II University of Lublin); Maurice Jackson (Georgetown University, Washington); Irena Machaj (University of Szczecin); Darina Malova (Comenius Uniwersity, Bratislava); Oleg Manaev (Belarusian State University, Minsk); Aleksander Manterys (Collegium Civitas, Warsaw); Janusz Mucha (University of Science and Technology, Kraków); Ryszard Radzik (Maria Grzegorzewska University, Warsaw); Mykoła Riabczuk (Ukrainian Centre for Cultural Studies, Kyiv); Józef Styk (Maria CurieSkłodowska University, Lublin); Bogdan Szajkowski (University of Exeter); Marek Szczepański (University of Silesia, Katowice); Adam A. Zych (University of Lower Silesia, Wroclaw). Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief: Jarosław Chodak; Associate Editors: Joanna Bielecka-Prus (cultural anthropology, migrations, sociology of eduaction, qualitative research methodology); Agnieszka Kolasa-Nowak (sociological theory, historical sociology, systemic change in Poland); Wojciech Misztal (civil society, theories of democracy); Michał Nowakowski (sociology of the family, medical sociology, demography); Elżbieta Szul (economic sociology, economics); Artur Wysocki (sociology of culture, sociology of nations, macrosociology); Statistical -

February 2020

The Runner February 2020 In 2011, an anonymous producer in Los Angeles released a spoof video featuring the image The First of artist Rebecca Black appearing to sing her song “Friday” (which became a “hit”, oddly United enough, because so many people appeared to dislike it – but that’s a story for another month). Presbyterian The version of “Friday” to which I refer was the launch of what has become a real internet sensation: Bad Lip Reading. The premiere video features all of the images from the original Church video, but all of the lyrics have been replaced by a description of a gang fight. of Crafton After “Friday/Gang Fight” was released, it was followed by a number of other songs that Heights were given the Bad Lip Reading treatment. In each case, the original artists appeared to be singing something that was nonsensical, incongruous, or even antithetical to the message of David B. Carver, the original tune. And then in September of 2011, the producer behind these efforts struck Pastor gold when he matched portions of a speech given by Presidential hopeful Rick Perry with invented dialogue that seemed to fit his lip movements perfectly. After that aired on the Ellen show, a genre was born – or at least defined. If you were to Google “Bad Lip Reading”, you’d discover that every major and many minor politician has been the subject of these satirical barbs, along with the NFL, the royal wedding, The Hunger Games, and dozens of others. 50 Stratmore St Pittsburgh, PA The “recipe” for each episode is the same: video footage plays of a movie or a personality speaking, but the original audio has been removed and other dialogue inserted for comedic or 15205-3640 sarcastic effect. -

Neuroimaging Studies on Familiarity of Music in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Neuroimaging Studies on Familiarity of Music in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder by Carina Patricia De Barros Freitas A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Degree of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Carina Patricia De Barros Freitas 2020 Neuroimaging Studies on Familiarity of Music in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Carina Patricia De Barros Freitas Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2020 Abstract The field of music neuroscience allows us to use music to investigate human cognition in vivo. Examining how brain processes familiar and unfamiliar music can elucidate underlying neural mechanisms of several cognitive processes. To date, familiarity in music listening and its neural correlates in typical adults have been investigated using a variety of neuroimaging techniques, yet the results are inconsistent. In addition, these correlates and respective functional connectivity related to music familiarity in typically developing (TD) children and children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are unknown. The present work consists of two studies. The first one reviews and qualitatively synthesizes relevant literature on the neural correlates of music familiarity, in healthy adult populations, using different neuroimaging methods. Then it estimates the brain areas most active when listening to familiar and unfamiliar musical excerpts using a coordinate-based meta-analyses technique of neuroimaging data. We established that motor brain structures were consistently active during familiar music listening. The activation of these motor-related areas could reflect audio-motor synchronization to elements of the music, such as rhythm and melody, so that one can tap, dance and “covert” sing along with a known song. -

Us Presidential Debates 2020

US PRESIDENTIAL DEBATES 2020 englishvillage.eu/2016/02/05/us-presidential-debates-lesson-plan WARM UP ● Q & A See what knowledge students already have of current president, vice president, presidential candidates, their stands on issues, election process etc (5-10mins) HOW AMERICA ELECTS 1. Who can run for President? 2. Campaign Finance 3. Polls and Debates 4.Caucuses and Primaries youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcEvTKITlt-4tvPdVVDpcQCHpvH7KaP1R HOST A PRESIDENTIAL DEBATE LESSON pbs.org/newshour/extra/lessons-plans/host-a-presidential-debate-lesson-plan The Materials You Need ● Lesson Plan – Hosting a Presidential Debate ● Handout 1 Techniques of Persuasion and Logical Fallacies ● Handout 2 Debate Watch Notes ● Handout 3 Debate Ballot ● Handout 4 Debate Arguments Template ● Handout 5 History of Presidential Debates ● Handout 6 Note on Fact Checking ● Handout 7 Words Count CANDIDATE STANDS ON ISSUES + QUOTES + CANDIDATE BIO Donald Trump Mike Pence Joe Biden Kamala Harris STANCE (OPINIONS) ON ISSUES issues2000.org/Donald_Tr issues2000.org/Mike_Pe .issues2000.org/Joe_Bi issues2000.org/Kamala_Har ump nce den ris QUOTES ON ISSUES ACTIVITIES Students in teams of 4 or 5 represent various candidates and prepare a debate based on actual candidate political views Handout 5 History of Presidential Debates 1. Kennedy-Nixon first debate, 1960: https://youtu.be/QazmVHAO0os 2. Reagan debates interview, 1989: https://youtu.be/T43EzCUtSwQ 3. Bush-Clinton debate, 1992: https://youtu.be/7ffbFvKlWqE 4. Obama-Romney final debate, 2012: https://youtu.be/5z0WrEb6p6I 5. Clinton-Trump debate, 2016: https://youtu.be/s7gDXtRS0jo US Presidential Debates 2016 Warm up ● Q & A See what knowledge students already have of current president, vice president, presidential candidates, election process etc (5mins) ● Just 4 Fun! “Bad Lip Reading” These videos can be used as a light introduction.