Rabsel Volume -V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical & Biological Sciences Merit Ranking

Medicine&Biological Sciences 2021 Merit List of Registered Candidates for Medicine & Biological Sciences 2021 (Min. 60% marks each in Physics, Chemistry, Biology and 55% in English) Index Number School Name CID Sex Stream MATHS ENGLISH PHYSICS BIOLOGY Merit Rank Total Marks Total DZONGKHA CHEMISTRY Application Number CHEMISTRY + BIOLOGY ) + BIOLOGY CHEMISTRY Total ( ENGLISH + PHYSICS Total 1 941_2104S02065 Seisa Kokusai High School Nidup Dorji M 11504002968 SCIENCE 94 93 93 94 90 374 464 2 941_2104S00822 12200260018 UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL Ugyen Thukzom F 10701001905 SCIENCE 90 99 94 81 80 90 363 534 3 941_2104S00311 12200020001 YANGCHENPHUG HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL Rekha Chhetri F 11203002997 SCIENCE 89 93 93 73 83 91 358 522 4 941_2104S00198 12200260027 UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL Ngawang C Gyeltshen M 11407002491 SCIENCE 90 95 94 75 76 355 430 5 941_2104S00560 12200260083 UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL Tashi Lhendrup Dorji M 10101005811 SCIENCE 88 93 96 75 76 86 353 514 6 941_2104S00092 12200260036 UGYEN ACADEMY HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL Rohan Rai M 11205001712 SCIENCE 89 94 94 66 74 83 351 500 7 941_2104S01241 12200160179 NANGKOR CENTRAL SCHOOL Pema Tshomo F 10903001512 SCIENCE 87 93 88 81 82 350 431 8 941_2104S00911 12201390133 KARMA ACADEMY Tandin Choda M 11905001182 SCIENCE 91 89 92 78 78 350 428 9 941_2104S02353 12201390157 KARMA ACADEMY Sonam Tshomo F 10804001035 SCIENCE 87 92 93 79 77 349 428 10 941_2104S01380 12200620015 TENDRUK CENTRAL SCHOOL Roshan Phuyel M 11206002979 SCIENCE 92 88 90 79 78 348 -

BHUTAN BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION COMPLEX ( Livingliving Inin Harmonyharmony Withwith the the Naturenature )

BHUTAN BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION COMPLEX ( LivingLiving inin harmonyharmony withwith the the NatureNature ) A Landscape Conservation Plan: a way forward. Prepared by Nature Conservation Division, Dept. of Forestry Services, Ministry of Agriculture, with support from WWF Bhutan Program Thimphu, February 2004 Pictures: Minama Sherpa, Yogesh Tamang, NCD and WWF Bhutan Collection White Bellied Heron, cover page, Oc Thinley Namgyel. NEC (1998) The Middle Path: Bhutan’s national environment strategy. National ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN Environment Commission, Thimphu. MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE TASHICHHODZONG NEC (2000) Environmental Assessment Act, 2000. National Environment Commission, THIMPHU, BHUTAN Thimphu. Norbu UP (1998) Human-Nature Interactions and Protected Area Management: A study “Walking the Extra Mile” of the situation in Lower Kheng part of Royal Manas National Park. Unpublished M.Sc. thesis, University of Wales, Aberystwyth, UK. FOREWORD Norbu UP (1999) From Islands to a Network. Panda Quarterly Summer 1999, WWF Bhutan Programme newsletter. Bhutan Biological Conservation Complex (B2C2) is one of the most ambitious programmes Norbu UP (2002) Two Years and Beyond: Report of the biennial programme review of of Nature Conservation Division that looks at conservation at landscape- level. Through the UNDP/GEF Small Grants Programme in the Kingdom of Bhutan. UNDP/GEF Small this programme an effort is made to reinforce, and translate Nature Conservation Division’s Grants Programme, Thimphu. Vision and Strategy 2003 into a holistic and landscape- approach that would eventually Norbu UP (2003) A Report of the Assessment of ICDP Activities in Bumdeling Wildlife sustain the country’s diverse ecosystems. Sanctuary. Report prepared for Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forestry Services, Ministry of Agriculture, and Environment Sector Programme Support, Danida, Key characteristics of the programme include: focus on biodiversity conservation in Thimphu. -

25 Years a King: His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck

A KING FOR ALL TIMES In June 1999 the people of Bhutan gather to rejoice in the celebration of the Silver Jubilee of His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck On 2 June 1999, the Kingdom of Bhutan celebrating a beloved monarch, the reverence and celebrates the 25th anniversary of the reign of His loyalty that the Bhutanese people have for their Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, King of King is rare, if not unique, in the world. Bhutan. During this momentous occasion the Bhutanese people will commemorate the His Majesty the King is the only son of five outstanding achievements of His Majesty's reign children born to His Lace Majesty Jigme Dorji and pay homage to him for his efforts in Wangchuck and Queen Mother Ashi Kesang promoting their prosperity and happiness. His Choden Wangchuck. His birth on 11 November Majesty's enlightened and energetic leadership has 1955 not only ensured an heir to the throne, but won him the affection and respect of the people of augured well for a bright and secure future for Bhutan, as well as the admiration of the world. Bhutan. His education in both Buddhist and While. Bhutan is perhaps no different from other modern curricula began at the age, of seven. Later, kingdoms in he studied at St. Joseph's College in Darjeeling, India, and in London, where he experienced the His Majesty and his parents: His Late Majesty life of an ordinary student. The lessons he learnt Jigme Dorji Wangchuck and the Queen Mother abroad were brought into harmony with everything Ashi Kesang Choden Wangchuck. -

Membership Contribution of Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, 2020

Membership Contribution of Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, 2020 Membership # Name Present Address Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Type 1 10040122 10040122 Lumpsum 2 10058340 Thimphu Yearly 3 1980's Group Thimphu Lumpsum 4 Akendra Prasad Sharma DGPC Yearly 5 Am Dawa Zam Am Dawa Zam Monthly 6 Am Mekio Am Mekio Lumpsum 6000 5000 7 Anita Kumar Rai PHPA 1 Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 8 Anju Chhetri Sherubtse College Half-yearly 9 Arun Prasad Timsina PHPA-1 Monthly 100 100 100 100 10 Aum Pem Zam Aum Pem Zam Lumpsum 11 Bank of Bhutan Thimphu Lumpsum 12 Bimal Kumar Chetri Sherubtse College Half-yearly 13 Buddha Mani Khatievara Sherubtse College Half-yearly 14 Chador Phuntsho BPC, Thimphu Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 15 Chador Wangdi Samdrup Jongkhar Monthly 16 Chador Wangmo SD Eastern Bhutan Coal Company Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 17 Chang D Tshering Chang D Tshering Lumpsum 18 Cheadup RBP Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 19 Cheki Wangmo BTL, Samdrup Jongkhar Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 20 Cheki Wangmo Bhutan Alternative Dispute Resolution Center Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 21 Cheku Dorji SJI Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 22 Chencho Gyeltshen PHPA 1 Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 100 23 Chencho Tshering College of language and Culture studies Monthly 50 50 50 50 50 50 24 Chencho Tshering BPC, Thimphu Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 25 Chencho Tshering Thimphu Yearly 26 Chencho Wangmo PHPA 1 Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 27 Chesung Dorji Dewathang Hospital Monthly 100 100 100 100 100 28 Cheten Norbu DGPC Yearly 29 Cheten -

Speech of the Hon. Speaker Jigme Zangpo at the Opening Ceremony of the Seventh Session of the Second Parliament of Bhutan

Speech of the Hon. Speaker Jigme Zangpo at the Opening Ceremony of the Seventh Session of the Second Parliament of Bhutan 1. Today, on behalf of the Members of Parliament and on my own behalf, I would like to welcome and express gratitude to Your Majesty for gracing the Opening Ceremony of the Seventh Session of the Second Parliament. I would also like to welcome Her Majesty the Gyaltsuen, Members of the Royal Family, representatives from the monastic body, senior Government officials, Armed Force personnel, diplomats and the public to the ceremony. 2. As everyone is aware, this year is indeed an extraordinary and a historic one for Bhutan and the Bhutanese people. As the saying goes, “Heaven holds the trinity of the sun, moon and the stars while earth holds the trinity of the King, Ministers and the People.” Today in Bhutan, there is peace in the country with great unity among the people, government and the gracious presence of Their Majesties. Moreover, I would like to submit that it is truly unprecedented in the history of Bhutan to witness and serve under the dynamic leadership of His Majesty the King, His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo and the Gyalsey Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck in a single period. The Bhutanese people cannot be more prosperous than today. 3. I would like to submit here that it is remarkable to witness Her Majesty the Grandmother Kezang Choedon Wangchuck, Her Majesty Queen Mothers Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck, Tshering Pem Wangchuck, Tshering Yangdon Wangchuck and Sangay Choden Wangchuck, and Her Majesty the Gyaltsuen Jetsun Pema Wangchuck for having carried out royal aspirations Page 1 of 5 of His Majesty under their patronage for the welfare of the Country and the people which remain an extraordinary symbols. -

RLG470H Hindu and Buddhist Royalty

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO MISSISSAUGA Course Syllabus: Advanced Topics in Buddhism: Hindu and Buddhist Royalty (RLG 470H5F) Course hours: Friday 1-3 pm Course venue: NE 228 Instructor: Christoph Emmrich Email: [email protected] Office hours: Fridays, 12-1 pm and on appointment Office: 297A NE Phone: 416-317-2662 1 Course description In contrast to traditional scholarship, which has focussed mainly on the literary and doctrinal models underlying South and Southeast Asian kingship, this course will take these models as the ideological lens through which to explore how concrete historical Hindu and Buddhist royal families have performed their religion. In dealing with figures such as Maharaja Sayaji Rao Gaekwad III of Baroda, Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur, or King Sihanouk of Cambodia, or Buddhist royal family lines such as the Konbaung, Shaha, Chakri and Wangchuk dynasties of Bhutan, Burma, Nepal and Thailand, respectively, the course will try to understand the aesthetics and semiotics of royal pageantry, the material culture of courtly temple ritual, the role of patriarchy, militarism and nationalism, the intellectual and institutional preoccupations with doctrine, practice and the royal mission as well as the interface of religious aura and celebrity culture. The course will begin by introducing students to ancient, local and modern South and Southeast Asian cosmologies of royal power in which Hindu and Buddhist ideologies form an inextricable whole. They comprise the concept of the “wheel-turning monarch” embodied by king Aśoka, the king as Viṣṇu represented by medieval Indian monarchs, as well as contemporary models such as those elaborated by Arthur Maurice Hocart and particularly Stanley Tambiah. -

Royal Family Tree of Bhutan

The Royal Family Tree of Bhutan Yum Tima Yab Rigzin Pema Yum Bumdren alias Sithar M Lingpa (1450-1521) M Peling Say Khedrup Wangmo, Peling Say Drakpa Drakpa Kunchog Gyalsay Dawa Gyeltshen Kinga Wangchuck / M Descendant of Ache Ugyen Gyelpo Gyelpo Zangpo Sangdag Wangpo (b. 1505) Guru Choewang Choje Ngawang Tsheten Gyelmo Karma Leyzom, Descendant Choje Kuenga Phogla alias M of Guru Choewang Wangchen Gyeltshen Sanga Dungkar Choje Paro Penlop M Tamzhing Choeje Jakar Dung Khic'og Zam Galay Bac'og Choje Drekha Choje Langkha M Nim Dorji Wangzom Penlop Ugyen Phuntsho Rinchen Pemo Chogley Yeshey Zimpon Ngodrup (5th Speech Choenzo Zam Pila Gonpo Dungkar Sangay M Pala Gyeltshen Drega C'anglong Gompa Incarnation ) Wangyal M Sonam Pemo 3rd Wife Khelma Dzongpon Sharpa Kitshelpa Dorji Gangzur Zhelngo Yum Pema Dungkar Tshering Lhundzongpa Desi Jigme Yum Pema Sangay 8th Sungtrul Jakar Penlop Jakar Dung Paro Tsentop M Dungkar Jigme 2nd Wife from M M Chukpo alias M M Nob Gyeltshen M Phenkem Penchung Namgyel Tshewang Choki's Sister, M Dolma of Khuay Dorji Namgyel Choki Lhamo Tenpai Nyima Pema Tenzin Ngedup Pemo Tashigang Thinley Pem Gyeltshen Lhuntse Jang Tshewang Jemo M Kesang Doma Sangay Lhamo Tangbi Naktshang Dzongpon , Ugyen M 1st Wife, Ney Chukpo Zamo Kuenga 5th Sersang Lam Maharaja Thimphu Dungkar Ashi Trongsa Dronyer Lhuntse Zimpon Zhemgang 2nd HM Queen, Sonam Tenzin Wangdicholing Ashi Ngodrup Gongzim Kazi Zhongar Namgyel Ugyen HM Ugyen Jakar Nyerchen Penlop Thinley Jakar Dzongpon 1st HM Queen Tashigang Gyeltshen alias M Gyeltshen Dorji Thuptop Dzongpon -

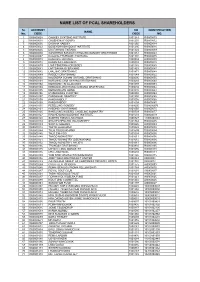

Name List of Pcal Shareholders

NAME LIST OF PCAL SHAREHOLDERS Sl. ACCOUNT CD IDENTIFICATION NAME No. CODE CODE NO. 1 1000000028 CHOKEY GYATSHO INSTITUTE 1001244 RI0000010 2 1000000030 CHUENGNAY GOMPA 1001250 RI0000012 3 1000000035 DAGANA RABDEY 1001260 RI0000014 4 1000000042 DODEYDRA BHUDDIST INSTITUTE 1001295 RI0000016 5 1000000046 DRATSHANG TSIRANG 1001324 RI0000019 6 1000000050 GANGTENG SANGAG CHHOLING GOMDEY DRATSHANG 1001051 RI0000023 7 1000000067 KAGUNG PHURSUM LHAKHANG 1001392 RI0000035 8 1000000070 KANJUR LHAKHANG 1000534 RI0000038 9 1000000072 KHAMLING LHAKHANG 1000393 RI0000040 10 1000000079 LAMI TSHERKHA DRUBDEY 1001183 RI0000045 11 1000000081 LAPTSAKHA GYERWANG 1001463 RI0000047 12 1000000082 LHALUNG DRATSHANG 1001471 RI0000048 13 1000000089 RABDEY DRATSHANG 1001549 RI0000052 14 1000000092 NALENDRA SONAM GATSHEL DRATSHANG 1000695 RI0000055 15 1000000101 NOBGANG CHULAKHANG DRATSHANG 1000693 RI0000060 16 1000000102 NORGANG TSHULAKHANG 1001093 RI0000061 17 1000000104 NOBGANG ZIMCHUNG GONGMA DRATSHANG 1000694 RI0000062 18 1000000105 NORGANG ZAI-GONG 1001030 RI0000063 19 1000000106 NYIZERGANG CHORTEN 1000803 RI0000064 20 1000000107 PANGKHAR, DROPDEY 1001500 RI0000065 21 1000000108 PARO RABDEY 1001005 RI0000066 22 1000000109 PARO RABDEY 1001009 RI0000067 23 1000000115 PESELLING GOMDEY 1000005 RI00000070 24 1000000121 RABDHEY DRATSHANG 1001060 RI0000075 25 1000000125 RANGJUNG WOESEL CHOELING MONASTRY 1000739 RI0000077 26 1000000127 RINCHENLING BUDDHIST INSTITUTE 1001558 RI0000079 27 1000000128 SAMTEN TSEMU LHAKHANG 1000827 11905000161 28 1000000134 SHA DECHENCHOLING -

List of Civil Servants Whose CV Corrections Have Been Effected in the CSIS Recently

List of Civil Servants whose CV corrections have been effected in the CSIS recently Regular or SI.NoName EID Working Agency Contract 1 Rudra Mani Dhimal 2001022 Administration & Finance Division,Secretariat Services, Ministry of Health Regular 2 Tashi Pem 2003010 Secretariat,Ministry of Finance Regular 3 Jamba 2006057 Agriculture Division,Department of Agriculture,Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Regular 4 Wangchuk 2007143 JDW National Referral Hospital,Hospital Services,Department of Medical Services,Ministry of Health Regular 5 Kezang Dawa 2008086 Menbi,RNR EC,Lhuntse Dzongkhag Regular 6 Chandra Ghalay 2008127 RNR Section,Samtse Dzongkhag Regular 7 Nim Dorji 2008182 Martshala Primary School, Samdrup Jongkhar Regular 8 Kuenzang Dorji 2008219 Thongrong Community School, Trashigang Dzongkhag Regular 9 Tashi Tshering 2008255 Denchukha Lower Secondary School, Samtse Dzongkhag Regular 10 Chhimi Rinzin 2008262 Zangkhar Primary School,Schools,Lhuntse Regular 11 Pema Dorji 2011010 MoFA Regular BAFRA Thimphu,REGIONALS,Quality Control & Quarantine Division,Bhutan Agriculture & Food 12 Jamyang Phuntsho 2101017 Regulatory Authority (BAFRA),Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Regular 13 Melam Zangpo 2101034 System & Capacity Development Division,Department of Local Governance Regular 14 Karma Penjor Dorji 2101074 Department of Hydro‐Power & Power‐System, MoEA Regular 15 Namgay Zangmo 2102002 RMS Lobeysa,Regional Division/Field,Department of Roads,Ministry of Works & Human Settlement Regular 16 Sonam 2103004 Jonkar BHU Regular 17 Shankar Rai 2103011 -

Report of Mountain Echoes 2019

FESTIVAL REPORT 2019 Presented by Jaypee Group An India-Bhutan Foundation Initiative In association with Siyahi AUGUST 22-25, 2019 Thimphu, Bhutan FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE • Mountain Echoes Festival of Art, Literature and Culture is an initiative of the India Bhutan Foundation, in association with Siyahi. The festival is presented by the Jaypee Group. • Bhutan’s annual literary Gathering was held in Thimphu from 23 to 25 AuGust 2019 at Royal University of Bhutan and Taj Tashi with the inaugural on 22nd August at India House. • Rich with words and ideas , centered on the theme Many Lives, Many Stories, showcased stories that explored and celebrated the many elements of personal, professional, mental and spiritual success. • The milestone 10th edition saw a true example of a Global audience with thousands of people from all strata of Indian, International and Bhutanese society. • The festival brouGht toGether writers, bioGraphers, historians, environmentalists, scholars, photographers, poets, musicians, artists, film-makers to enGaGe in a cultural dialoGue, share stories, create memories and spend three blissful days in the mountains. CHIEF ROYAL PATRON OF MOUNTAIN ECHOES Her Majesty the Royal Queen Mother Ashi Dorji WanGmo WanGchuck FESTIVAL DIRECTORS Namita Gokhale Pramod K.G. TsherinG Tashi Kelly Dorji FESTIVAL PRODUCER Mita Kapur FESTIVAL PARTNERS INDIA BHUTAN FOUNDATION was established in AuGust 2003 by the Royal Government of Bhutan and the Government of India with the objective of enhancinG exchanGe and interaction amonG the people of both countries through activities in the areas of education, culture, science and technoloGy. JAYPEE GROUP is a well-diversified infrastructural industrial conglomerate in India. -

EMBASSY of INDIA, THIMPHU (Education Section) Registration No Name Bhutanese Citizenship ID Card No. 20200003 Mr.Siddharth Pradh

EMBASSY OF INDIA, THIMPHU (Education Section) Registration Name Bhutanese Citizenship No ID Card No. 20200003 Mr.Siddharth Pradhan 11803002975 20200004 Ms.Tenzin Lhaden 11410008890 20200005 Ms.Pema yangzom 11505003030 20200008 Ms.Kinley Zangmo 11407000628 20200011 Mr.KARMA LEKSHAY WANGPO 10304000053 20200013 Ms.PemaTshomo 12007003074 20200014 Mr.KARMA SAMTEN DORJI 11407000600 20200019 Ms.Karma Dema 10202000438 20200024 Ms.Sangay Choden 10709005302 20200029 Mr.Karma wangchuk 10101004120 20200030 Ms.Dechen Pemo 11513006222 20200031 Ms.Jigme Wangmo 11512005448 20200033 Ms.Anisha Ghalley 11303000188 20200034 Ms.Kinley Choden 10904002963 20200035 Mr.Tshering zam 10202000439 20200037 Ms.Kezang Choden 11514001637 20200038 Ms.DIPIKA POKWAL 11804000702 20200039 Ms.Sonam Tshomo 10807001153 20200040 Ms.Kinley Om 10202000437 20200041 Ms.Sonam chokey 11705000500 20200042 Mr.Yeshi Tshering 11101000872 20200043 Ms.Legzin Wangmo 11405000748 20200044 Ms.Priyarna Gurung 11110000073 20200045 Ms.Pritam Ghalley 11204002078 20200046 Ms.Kamala Devi Rizal 11310000604 20200047 Mr.Reshi Prasad Pokhrel 11109001849 20200048 Mr.NIKITA RAI 11211001762 20200049 Mr.Sonam Tobgay 10807002319 20200050 Mr.Dhan Kumar Adhikari 20200005102 20200051 Mr.Ngawang Dorji 10808001072 20200052 Ms.Yangchen Dema 11106003859 20200053 Mrs.Tshewang Lhamo 11303003231 20200054 Ms.Gaygye Nima Tamang 10201000093 20200055 Mr.Kinley Rabgay 11704003371 20200056 Mr.Shajan Gurung 11201000367 20200057 Mr.Chimi Tenzin Wangchuk 11107001527 20200058 Mrs.Choney Zangmo 11312001321 20200059 Mrs.Sonam -

Contemporary Bhutanse Literature

འབྲུག་དང་ཧི་捱་ལ་ཡ། InternationalInternational Journal for Journal Bhutan & Himalayan for Research Bhutan & Himalayan Research Bhutan & Himalaya Research Center College of Language and Culture Studies Royal University of Bhutan P.O.Box 554, Taktse, Trongsa, Bhutan Email: [email protected] Bhutan & Himalaya Research Centre College of Language and Culture Studies Royal University of Bhutan P.O.Box 554, Taktse, Trongsa, Bhutan Email: [email protected] Copyright©2020 Bhutan and Himalaya Research Centre, College of Language and Culture Studies, Royal University of Bhutan. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this publication are those of the contributors and not necessarily of IJBHR. No parts of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without permission from the publisher. Printed at Kuensel Corporation Ltd., Thimphu, Bhutan Articles In celebration of His Majesty the King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck’s 40th birth anniversary and His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo Jigme Singye Wangchuk’s 65th birth anniversary. IJBHR Inaugural Issue 2020 i འབྲུག་དང་ཧི་捱་ལ་ཡ། International InternationalJournal for Journal for Bhutan & Himalayan Research BhutanGUEST EDITOR & Himalayan Holly Gayley UniversityResearch of Colorado Boulder, USA EDITORS Sonam Nyenda and Tshering Om Tamang BHRC, CLCS MANAGING EDITOR Ngawang Jamtsho Dean of Research and Industrial Linkages, CLCS EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bhutan & Himalaya