PROGRAM NOTES DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE (The Magic Flute) WILLIAM INTRILIGATOR, Music Director & Conductor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic Flute Synopsis

Mozart’s The Magic Flute Synopsis ACT I Three ladies in the service of the Queen of the Night save the fainting Prince Tamino from a serpent (“Zu Hülfe! zu Hülfe!”). When they leave to tell the queen, the bird catcher Papageno bounces in and boasts to Tamino that it was he who killed the creature (“Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja”). The ladies return to give Tamino a portrait of the queen’s daughter, Pamina, who they say is enslaved by the evil Sarastro, and they padlock Papageno’s mouth for lying. Tamino falls in love with Pamina’s face in the portrait (“Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön”). The queen, appearing in a burst of thunder, is grieving over the loss of her daughter; she charges Tamino with Pamina’s rescue (“Zum Leiden bin ich auserkoren”). The ladies give a magic flute to Tamino and silver bells to Papageno to ensure their safety, appointing three spirits to guide them (“Hm! hm! hm! hm!”). Sarastro’s slave Monostatos pursues Pamina (“Du feines Täubchen”) but is frightened away by the feather-covered Papageno, who tells Pamina that Tamino loves her and intends to save her. Led by the three spirits to the Temple of Sarastro, Tamino is advised by a high priest that it is the queen, not Sarastro, who is evil. Hearing that Pamina is safe, Tamino charms the animals with his flute, then rushes to follow the sound of Papageno’s pipes. Monostatos and his cohorts chase Papageno and Pamina but are left helpless by Papageno’s magic bells. Sarastro, entering in great ceremony (“Es lebe Sarastro”), promises Pamina eventual freedom and punishes Monostatos. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Franz Schubert Wolfgang

STIFTUNG MOZARTEUM SALZBURG WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 FRANZ SCHUBERT SYMPHONY NO. 5 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART PIANO CONCERTO NO. 23 ANDRÁS SCHIFF CAPPELLA ANDREA BARCA WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Vienna - once the music hub of Europe - attracted all the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 greatest composers of its day, among them Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart. This concert given by András Schiff and FRANZ SCHUBERT the Capella Andrea Barca during the Salzburg Mozart Week Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, D 485 brings together three works by these great composers, which WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART each of them created early in life at the start of an impressive Piano Concerto No. 23 in E flat major, KV 482 Viennese career. The programme opens with Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto: Piano & Conductor András Schiff “Sensitively supported by the rich and supple tone of the strings, Orchestra Cappella Andrea Barca Schiff’s pianistic virtuosity explores the length and breadth of Beethoven’s early work, from the opulent to the playful, with a Produced by idagio.production palpable delight rarely found in such measure in a pianist”, was Video Director Oliver Becker the admiring verdict of the Salzburg press. Length: approx. 100' As in his opening piece, Schiff again succeeded in Schubert’s Shot in HDTV 1080/50i symphony “from the first note to the last in creating a sound Cat. no. A 045 50045 0000 world that flooded the mind’s eye with images” Drehpunkt( Kultur). A co-production of The climax of the concert was the Mozart piano concerto. -

Beethoven to Drake Featuring Daniel Bernard Roumain, Composer & Violinist

125 YEARS Beethoven to Drake Featuring Daniel Bernard Roumain, composer & violinist TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE 87TH Annual Young People’s Concert William Boughton, Music Director Thank you for taking the NHSO’s musical journey: Beethoven to Drake Dear teachers, Many of us were so lucky to have such dedicated and passionate music teachers growing up that we decided to “take the plunge” ourselves and go into the field. In a time when we must prove how essential the arts are to a child’s growth, the NHSO is committed to supporting the dedication, passion, and excitement that you give to your students on a daily basis. We look forward to traveling down these roads this season with you and your students, and are excited to present the amazing Daniel Bernard Roumain. As a gifted composer and performer who crosses multiple musical genres, DBR inspires audience members with his unique take on Hip Hop, traditional Haitian music, and Classical music. This concert will take you and your students through the history of music - from the masters of several centuries ago up through today’s popular artists. This resource guide is meant to be a starting point for creation of your own lesson plans that you can tailor directly to the needs of your individual classrooms. The information included in each unit is organized in list form to quickly enable you to pick and choose facts and activities that will benefit your students. Each activity supports one or more of the Core Arts standards and each of the writing activities support at least one of the CCSS E/LA anchor standards for writing. -

The Compositional Influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Early Period Works

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2018 Apr 18th, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works Mary L. Krebs Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Musicology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Krebs, Mary L., "The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works" (2018). Young Historians Conference. 7. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2018/oralpres/7 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCE OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART ON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S EARLY PERIOD WORKS Mary Krebs Honors Western Civilization Humanities March 19, 2018 1 Imagine having the opportunity to spend a couple years with your favorite celebrity, only to meet them once and then receiving a phone call from a relative saying your mother was about to die. You would be devastated, being prevented from spending time with your idol because you needed to go care for your sick and dying mother; it would feel as if both your dream and your reality were shattered. This is the exact situation the pianist Ludwig van Beethoven found himself in when he traveled to Vienna in hopes of receiving lessons from his role model, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. -

The Magic Flute' and It’S Written by a Composer Called Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

I’VE NEVER BEEN TO THE OPERA BEFORE. WHAT’S IT GOING TO BE LIKE? It’s great fun! You can expect to hear lots of great music and acting. All operas tell a story with performers who act and sing on a stage in costume whilst a band of musicians (aka an orchestra) play along. The opera that you’ll be coming to see is called 'The Magic Flute' and it’s written by a composer called Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. E WASN'T MOZART AROUND A LONG TIME AGO? IS 'THE MAGIC FLUTE' A T REALLY OLD OPERA? U Yes, Mozart lived over 200 years ago and 'The Magic Flute' was first performed in 1791. However, all the costumes and the set are all brand spanking new and L of course all the people performing aren’t 200 years old! F The costumes, set, lighting and the way the performers act is what’s known as the production, all created by a team of people led by a director. You’ll be coming to see a new production of 'The Magic Flute' today. If you see another C production of 'The Magic Flute' in the future, it’ll look totally different to this one! I G IS THE WHOLE OF 'THE MAGIC FLUTE' SUNG? A Not all of it. 'The Magic Flute' is a type of German opera called a ‘singspiel’ M which means there are several moments where the performers speak instead of singing. E DOES THIS MEAN THAT THE OPERA WILL BE IN GERMAN? H Yes it does! But don’t worry. -

What's a Christian to Do with the Magic Flute? Mysticism, Misogyny

What’s a Christian To Do With The Magic Flute? Masons, Mysticism, and Misogyny in Mozart’s Last Opera The libretto of Die Zauberflöte has generally been considered to be one of the most absurd specimens of that form of literature in which absurdity is regarded as a matter of course. - Edward J. Dent, 1913 It is in its infinite richness and variety, its inexhaustible capacity for the provision of new experience that the unique greatness of The Magic Flute lies as a work of art. - Patrick Cairns (“Spike”) Hughes, 1958 Introduction Perhaps no other opera has launched as much controversy, argument, or bewilderment as The Magic Flute. For the more than 200 years since its creation, scholars, musicologists, poets, psychologists, and critics, to name only a few, have pondered over and pontificated upon the intentions of its creators, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his collaborator, Emanuel Schikaneder. This paper is presented as a very limited response to some of the questions that have historically been raised concerning the content of the opera’s libretto. The title of this presentation has been unceremoniously lifted from Connie Neal’s excellent book, What’s a Christian To Do With Harry Potter? (2001), which was written in response to the concerns of conservative Christian parents when confronted with the phenomenal success of the Harry Potter novels. In defense of Harry (and author J. K. Rowling), Neal chose passages from the books and discussed their positive, life-affirming content, outlining spiritual lessons that could be extracted from these segments. Although Mozart’s work needs no apology, some explanation of certain passages may provide enlightenment, or even edification. -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Béla Bartók Franz Schubert

JANUARY 22, 2016 – 7:30 PM WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Quartet for Flute and Strings in C Major, K. 285b Allegro Andantino Lorna McGhee flute / Erin Keefe violin / Rebecca Albers viola / Robert deMaine cello BÉLA BARTÓK Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano, Sz. 75 Allegro appassionato Adagio Allegro James Ehnes violin / Andrew Armstrong piano INTERMISSION FRANZ SCHUBERT Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano in E-flat Major, Op. 100, D. 929 Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo: Allegro moderato Allegro moderato Alexander Kerr violin / Edward Arron cello / Max Levinson piano SEASON SPONSORSHIP PROVIDED BY JAMES F. ROARK, Jr. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART color and fairness to the other players, variations (1756–1791) two and three are led respectively by the violin and Quartet for Flute and Strings in C Major, cello. De rigueur Mozart moves into the darker C K. 285b, K. Anh. 171 (1778) minor for the fourth variation. Having enriched the harmonic color there, he shifts into a slower Adagio Mozart famously complained to his father that for No. 5, perhaps the loveliest in the set. The he detested the flute, a sour declaration that concluding variation returns to C major in a spirited probably drew added venom from his unhappiness dance-like gesture with folk-like intimations. with having to ply his trade in provincial Salzburg in the employ of his formidable foe, Archbishop BÉLA BARTÓK Hieronymus Colloredo. He also griped about (1881–1945) the paltry recompense offered for the task of Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano, Sz. 75 composing several pieces commissioned by a (1921) wealthy amateur flutist named De Jean. -

Major Themes in the Magic Flute Filled with Ritual and Symbolism

Major Themes in The Magic Flute Filled with ritual and symbolism, Mozart’s final masterpiece is a playful but profound look at man's search for love and his struggle to attain wisdom and virtue. From the virtuosic arias of the Queen of the Night to the folksong-like melodies of the bird catcher Papageno, the full range of Mozart's miraculous talent is on display in this magical fairy-tale opera. That The Magic Flute is a barely veiled Masonic allegory cannot be doubted. It acts, in fact, as a kind of introduction to the secret society. Its story celebrates the main themes of masonry: good vs. evil, enlightenment vs. ignorance, and the virtues of knowledge, justice, wisdom and truth. The evocation of the four elements (earth, air, water and fire), the injunction of silence in the Masonic ritual, the figures of the bird, the serpent and the padlock as well as the ‘rule of three’ all play important roles in the plot or in the musical fabric of the opera (three ‘Ladies’, three ‘Boys’, three loud chords at the beginning of the overture signifying the three ‘knocks’ of the initiates at the temple, three temples, the three flats of E-flat Major which is the primary tonality of the work, etc.) All of these symbols and characteristics come from Egyptian lore and the various original texts of Masonry; hence the opera’s libretto is set in Egypt, although many productions eschew that specification. Sources: operapaedia.org & sfopera.com Definition of Freemasonry (the Masonic order) Freemasonry is a fraternal organization that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. -

Idomeneo Synopsis

Idomeneo Synopsis Background Helen, the beautiful wife of King Menelaus of Greece, was carried off by Paris, son of King Priam of Troy, triggering the Trojan War. Agamemnon, Menelaus's brother, rallied the other Greek kings and joined forces to lay siege to the city of Troy. One of Agamemnon's allies was King Idomeneo of Crete, whose army helped to deliver a victory over the Trojans. After ten long years of war, Idomeneo is finally on his way home. Some of his forces have already returned, bringing back Trojan captives including Priam's daughter, Princess Ilia. The ship carrying Ilia was hit by a storm and sank, but she was rescued from the waves by Idomeneo's son, Idamante. Upon his own return from war, Agamemnon was murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus; Elettra's brother, Orestes, took revenge on the unfaithful by killing them both. Elettra fled from their home in Argos, and is now taking refuge in Crete. ACT I Island of Crete, c. 1200 B.C. At the palace, Ilia is grieving for her father and brothers who were killed by the Greek army in the siege on Troy. But while she hates Idomeneo, she has fallen in love with his son, Idamante, who has ruled Crete in his father's absence ("Padre, germani, addio!"-Father, brothers, farewell!). Although Idamante proclaims his love for her, Ilia, cannot bring herself to admit her feelings for him ("Non ho colpa"-I am not guilty). As a gesture of goodwill, Idamante releases the Trojan captives; they join the Cretans in rejoicing this newfound peace ("Godiam la pace"-Let us enjoy peace). -

Mozart's Operas, Musical Plays & Dramatic Cantatas

Mozart’s Operas, Musical Plays & Dramatic Cantatas Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebotes (The Obligation of the First and Foremost Commandment) Premiere: March 12, 1767, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Apollo et Hyacinthus (Apollo and Hyacinth) Premiere: May 13, 1767, Great Hall, University of Salzburg Bastien und Bastienne (Bastien and Bastienne) Unconfirmed premiere: Oct. 1768, Vienna (in garden of Dr Franz Mesmer) First confirmed performance: Oct. 2, 1890, Architektenhaus, Berlin La finta semplice (The Feigned Simpleton) Premiere: May 1, 1769, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Mitridate, rè di Ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus) Premiere: Dec. 26, 1770, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan Ascanio in Alba (Ascanius in Alba) Premiere: Oct. 17, 1771, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan Il sogno di Scipione (Scipio's Dream) Premiere: May 1, 1772, Archbishop’s Residence, Salzburg Lucio Silla (Lucius Sillus) Premiere: Dec. 26, 1772, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan La finta giardiniera (The Pretend Garden-Maid) Premiere: Jan. 13, 1775, Redoutensaal, Munich Il rè pastore (The Shepherd King) Premiere: April 23, 1775, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Thamos, König in Ägypten (Thamos, King of Egypt) Premiere (with 2 choruses): Apr. 4, 1774, Kärntnertor Theatre, Vienna First complete performance: 1779-1780, Salzburg Idomeneo, rè di Creta (Idomeneo, King of Crete) Premiere: Jan. 29, 1781, Court Theatre (now Cuvilliés Theatre), Munich Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) Premiere: July 16, 1782, Burgtheater, Vienna Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom) Composed: 1784, but the opera was never completed *Not performed during Mozart’s lifetime Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario) Premiere: Feb. 7, 1786, Palace of Schönbrunn, Vienna Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) Premiere: May 1, 1786, Burgtheater, Vienna Don Giovanni (Don Juan) Premiere: Oct. -

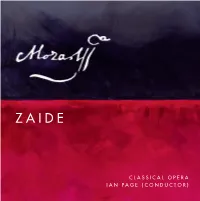

Classical Opera Ian Page (Conductor)

ZAIDE CLASSICAL OPERA IAN PAGE (CONDUCTOR) 7586_CO_Zaide_BOOKLET_FINAL.indd 1 13/06/2016 10:15 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 - 1791) ZAIDE, K.344 Libretto by Johann Andreas Schachtner (1731 - 1795) ZAIDE SOPHIE BEVAN soprano Performance material: New Mozart Edition (NMA) By kind permission of Bärenreiter-Verlag GOMATZ ALLAN CLAYTON tenor Kassel · Basel · London · New York · Praha Recorded at the Church of St. Augustine, Kilburn, London, UK from 10 to 13 March 2016 ALLAZIM JACQUES IMBRAILO baritone Produced and engineered by Andrew Mellor Assistant engineer: Claire Hay SULTAN SOLIMAN STUART JACKSON tenor Post-production by Andrew Mellor and Claire Hay Design by gmtoucari.com Cover image by Debbie Coates OSMIN DARREN JEFFERY bass-baritone Photographs by Benjamin Ealovega German language coaches: Johanna Mayr and Rahel Wagner VORSINGER JONATHAN McGOVERN baritone Harpsichord technician: Malcolm Greenhalgh ZARAM DARREN JEFFERY Orchestra playing on period instruments at A = 430 Hz We are extremely grateful to George and Efthalia Koukis for supporting this recording. SKLAVEN PETER AISHER, ROBIN BAILEY, We are also grateful to the following people for their generous support: Kate Bingham and Jesse Norman, Sir Vernon and Lady SIMON CHALFORD GILKES, Ellis, John Warrillow and Pamela Parker, Kevin Lavery, Pearce and Beaujolais Rood, John Chiene and Carol Ferguson, and all ED HUGHES, STUART LAING, the other individuals who supported this project. NICK MORTON, DOMINIC WALSH Special thanks to: Mark Braithwaite, Anna Curzon, Geoff Dann, Chris Moulton, Verena Silcher, Alice Bellini, Léa Hanrot, Simon Wall and TallWall Media. THE ORCHESTRA OF CLASSICAL OPERA Leader: Bjarte Eike IAN PAGE conductor 2 MOZART / ZAIDE MOZART / ZAIDE 3 zaide7586_CO_Zaide_BOOKLET_FINAL.indd booklet FINALEsther.indd 2 2-3 09/06/2016 15:58:54 zaide booklet FINALEsther.indd 3 09/06/201613/06/2016 15:58:54 10:15 ZAIDE, K.344 ACT ONE Page 1 [Overture – Entr’acte from Thamos, König in Ägypten, K.345] 3’23 32 2 No. -

Idomeneo” on Crete “

“Idomeneo” on Crete by Heather Mac Donald The humanists who created the first operas out to be his son, Idamante, whom, in Cam- in late sixteenth-century Florence hoped to re- pra’s opera, the king does indeed sacrifice be- capture the emotional impact of ancient Greek fore going mad. Such a dark ending no longer tragedy. It would take nearly another 200 years, suited Enlightenment tastes, however, and in however, for the most powerful aspect of Attic Mozart’s libretto, by the Salzburg cleric Giam- drama— the chorus—to reach its full potential battista Varesco, the gods grant Idomeneo a on an opera stage. That moment arrived with last-minute reprieve from his vow and rule is Mozart’s 1781 opera Idomeneo, re di Creta. This amicably passed from father to son. September, Opera San José performed Idome- The delight that Mozart must have had in neo’s sublime choruses with thrilling clarity and composing for the Mannheimers is palpable force, in a striking new production of the op- in Idomeneo’s dynamic score. And it is in the era that wedded a philanthropist’s archeologi- opera’s nine choruses that the orchestral writ- cal passion with his love for Mozart. San José’s ing reaches its pinnacle. In the celebrations Idomeneo was a reminder of the breadth of classi- of the Trojan War’s end—“Godiam la pace” cal music excellence in the United States, as well (“Let us savor peace”) and “Nettuno s’onori” as of the value of philanthropy guided by love. (“Let Neptune be honored”)—the strings In 1780, the twenty-four-year-old Mozart re- skitter jubilantly through complex rhythms ceived his most prestigious commission yet: to and rapid volume changes, while the winds compose an opera for the Court of Bavaria to embroider fleet counterpoint around the open Munich’s Carnival season.