The Diffcult Heritage of Non-Sites of Memory. Contested Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miriam Weiner Archival Collection

THE MIRIAM WEINER ARCHIVAL COLLECTION BABI YAR (in Kiev), Ukraine September 29-30, 1941 From the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kiev-and-babi-yar "On September 29-30, 1941, SS and German police units and their auxiliaries, under guidance of members of Einsatzgruppe C, murdered a large portion of the Jewish population of Kiev at Babi Yar, a ravine northwest of the city. As the victims moved into the ravine, Einsatzgruppen detachments from Sonderkommando 4a under SS- Standartenführer Paul Blobel shot them in small groups. According to reports by the Einsatzgruppe to headquarters, 33,771 Jews were massacred in this two-day period. This was one of the largest mass killings at an individual location during World War II. It was surpassed only by the massacre of 50,000 Jews at Odessa by German and Romanian units in October 1941 and by the two-day shooting operation Operation Harvest Festival in early November 1943, which claimed 42,000-43,000 Jewish victims." From Wikipedia.org https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babi_Yar According to the testimony of a truck driver named Hofer, victims were ordered to undress and were beaten if they resisted: "I watched what happened when the Jews—men, women and children—arrived. The Ukrainians[b] led them past a number of different places where one after the other they had to give up their luggage, then their coats, shoes and over- garments and also underwear. They also had to leave their valuables in a designated place. There was a special pile for each article of clothing. -

Sept. 19, 2019 Attorney General Phil Weiser to Address Hatred and Extremism at Holocaust Remembrance Ceremony

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Melanie Avner, [email protected], 720-670-8036 Attorney General Phil Weiser to Address Hatred and Extremism at Holocaust Remembrance Ceremony Sept. 22 Denver, CO (Sept. 19, 2019) – Attorney General Phil Weiser will give a special address on confronting hate and extremism at the Mizel Museum’s annual Babi Yar Remembrance Ceremony on Sunday, September 22 at 10:00 a.m. at Babi Yar Memorial Park (10451 E. Yale Ave., Denver). The event commemorates the Babi Yar Massacre and honors all victims and survivors of the Holocaust. “The rise in anti-Semitism and other vicious acts of hatred in the U.S. and around the world underscore the need to confront racism and bigotry in our communities,” said Weiser. “We must honor and remember the victims of the Holocaust, learning from the lessons of the past in order to combat intolerance and hate in the world today.” Weiser’s grandparents and mother survived the Holocaust; his mother is one of the youngest living survivors. She was born in the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, and she and her mother were liberated the next day by the Second Infantry Division of the U.S. Army. Nearly 34,000 Jews were executed at the Babi Yar ravine on the outskirts of Kiev in Nazi-occupied Ukraine on September 29-30, 1941. This was one of the largest mass murders at an individual location during World War II. Between 1941 and 1943, thousands more Jews, Roma, Communists and Soviet prisoners of war also were killed there. It is estimated that some 100,000 people were murdered at Babi Yar during the war. -

Collaboration and Resistance—The Ninth Fort As a Test Case

Aya Ben-Naftali Director, Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust Collaboration and Resistance: The Ninth Fort as a Test Case The Ninth Fort is one of a chain of nine forts surrounding the city of Kovno, Lithuania. In connection with the Holocaust, this location, like Ponary, Babi Yar, and Rumbula, marks the first stage of the Final Solution—the annihilation of the Jewish people. The history of this site of mass slaughtering is an extreme case of the Lithuanians’ deep involvement in the systematic extermination of the Jews, as well as an extraordinary case of resistance by prisoners there. 1. Designation of the Ninth Fort as a Major Killing Site The forts surrounding Kovno were constructed between 1887 and 1910 to protect the city from German invasion. The Ninth Fort, six kilometers northwest of the city, was considered the most important of them. In the independent Republic of Lithuania, it served as an annex of the central prison of Kovno and had a capacity of 250 prisoners. Adjacent to the fort was a state-owned farm of eighty-one hectares, where the prisoners were forced to work the fields and dig peat.1 The Ninth Fort was chosen as the main regional execution site in advance. Its proximity to the suburb of Vilijampole (Slobodka), where the Kovno ghetto had been established, was apparently the main reason. In his final report on the extermination of Lithuanian Jews, Karl Jäger, commander of Einsatzkommando 3 and the Security Police and SD in Lithuania, noted the factors that informed his choice of killing sites (Exekutionsplatze): …The carrying out of such Aktionen is first of all an organizational problem. -

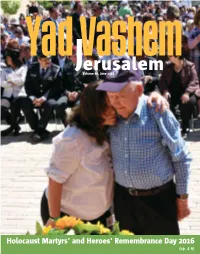

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Poland Study Guide Poland Study Guide

Poland Study Guide POLAND STUDY GUIDE POLAND STUDY GUIDE Table of Contents Why Poland? In 1939, following a nonaggression agreement between the Germany and the Soviet Union known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was again divided. That September, Why Poland Germany attacked Poland and conquered the western and central parts of Poland while the Page 3 Soviets took over the east. Part of Poland was directly annexed and governed as if it were Germany (that area would later include the infamous Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz- Birkenau). The remaining Polish territory, the “General Government,” was overseen by Hans Frank, and included many areas with large Jewish populations. For Nazi leadership, Map of Territories Annexed by Third Reich the occupation was an extension of the Nazi racial war and Poland was to be colonized. Page 4 Polish citizens were resettled, and Poles who the Nazis deemed to be a threat were arrested and shot. Polish priests and professors were shot. According to historian Richard Evans, “If the Poles were second-class citizens in the General Government, then the Jews scarcely Map of Concentration Camps in Poland qualified as human beings at all in the eyes of the German occupiers.” Jews were subject to humiliation and brutal violence as their property was destroyed or Page 5 looted. They were concentrated in ghettos or sent to work as slave laborers. But the large- scale systematic murder of Jews did not start until June 1941, when the Germans broke 2 the nonaggression pact with the Soviets, invaded the Soviet-held part of Poland, and sent 3 Chronology of the Holocaust special mobile units (the Einsatzgruppen) behind the fighting units to kill the Jews in nearby forests or pits. -

Timeline-Of-The-Holocaust.Pdf

The Holocaust, 1933 – 1945 Educational Resources Kit Timeline of the Holocaust: 1933 – 1945 1933 January 30 Adolf Hitler appointed Chancellor of Germany March 22 Dachau concentration camp opens April 1 Boycott of Jewish shops and businesses April 7 Laws for Reestablishment of the Civil Service barred Jews from holding civil service, university, and state positions April 26 Gestapo established May 10 Public burnings of books written by Jews, political dissidents, and others not approved by the state July 14 Law stripping East European Jewish immigrants of German citizenship 1934 August 2 Hitler proclaims himself Führer und Reichskanzler (Leader and Reich Chancellor). Armed forces must now swear allegiance to him 1935 May 31 Jews barred from serving in the German armed forces September 15 "Nuremberg Laws": anti-Jewish racial laws enacted; Jews no longer considered German citizens; Jews could not marry Aryans; nor could they fly the German flag November 15 Germany defines a "Jew": anyone with three Jewish grandparents; someone with two Jewish grandparents who identifies as a Jew 1936 March 3 Jewish doctors barred from practicing medicine in German institutions March 7 Germans march into the Rhineland, previously demilitarized by the Versailles Treaty June 17 Himmler appointed the Chief of German Police July Sachsenhausen concentration camp opens October 25 Hitler and Mussolini form Rome-Berlin Axis 1937 July 15 Buchenwald concentration camp opens Simon Wiesenthal Center-Museum of Tolerance Library & Archives For more information contact -

The Shoah in Ukraine in the Framework of Holocaust Studies

Ray Brandon, Wendy Lower, eds.. The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010. 392 pp. $25.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-253-22268-8. Reviewed by Stefan Rohdewald Published on H-Judaic (May, 2013) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) The volume originated in a workshop at the and the slaughter at Babi Yar seem to be “singular United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in episodes” or “most extreme examples” of the 1999. As explained in the introduction, the book pogroms of 1941 and the wave of mass shootings aims at contributing to a shift in the scholarly dis‐ (p. 5). The introduction gives a comprehensive course from the Holocaust in the Soviet Union to sketch of the topic, including a nod to Ukrainian the Holocaust in Ukraine, following the example rescue efforts, reflected in the recognition of 2,185 of research on the Shoah in Poland, Romania, and Righteous among the Nations from Ukraine by Hungary. The introduction thus discusses the Jews Yad Vashem by January 1, 2007. of Ukraine without forgetting to stress that they Dieter Pohl begins the series of contributions did not constitute a homogeneous community. by giving a survey of the Holocaust under German Jews are included in a Ukrainian framework, military and then civil administration as well as which should hinder the characterization of Jews the involvement of Ukrainian police, concentrat‐ as “external” victims, which is quite common in ing on the upper strata of the actors. He shows the Ukrainian context, as in most national con‐ how the mass killings in the framework of Ger‐ texts. -

Memorializing Babyn Yar

Linköping University - Department of Social and Welfare Studies (ISV) Master´s Thesis, 30 Credits – MA in Ethnic and Migration Studies (EMS) ISRN: LiU-ISV/EMS-A--19/06--SE Memorializing Babyn Yar: Politics of Memory and Commemoration of the Holocaust in Ukraine Galyna Kutsovska Supervisor: Peo Hansen TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations and Acronyms......................................................................................... vi Explanation of Definitions and Terminology ...........................................................................vii List of Illustrations.................................................................................................................. viii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 Background: The Holocaust – a Politically Charged Topic in Soviet Historical Culture ...... 1 Research Questions and Purpose ............................................................................................ 3 Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of Case Study ............................................................................................................ -

A Literature of Conscience: Yevtushenko's Post-Stalin Poetry

A Literature of Conscience: Yevtushenko’s Post-Stalin Poetry by Amy Kathleen Safarik A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Russian Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2008 ©Amy Kathleen Safarik 2008 ISBN 978-0-494-43798-8 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract The tradition of civic poetry occupies a unique place in the history of Russian literature. The civic poet (grazhdanskii poet) characteristically addresses socio-political issues and injustices relevant to the era in opposition to the established authority. This often comes out of a sense of responsibility to the nation. During the Thaw period (1953-63), an interval of relative artistic freedom that followed decades of severe artistic control, Y. Yevtushenko (1932- )was among the first poets who dared to speak critically about the social and political injustices that occurred during Stalin‘s dictatorship. At that time, his civic-oriented poetry focused primarily on the reassessment of historical, social, and political values in the post-Stalin era. The aim of the present study is to evaluate Yevtushenko‘s position within the tradition of civic poets and to illustrate his stylistic ability to combine lyrical intimacy and autobiographic experiences with national and international issues in the genre of civic poetry. I approach the subject using a methodology of close examination: a formal and structural analysis of select poems in the original Russian. -

Violins of Hope: Teacher's Guide

Teacher’s Guide sponsors: Dominion Energy WINDSOR Charitable Foundation FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview of Music During the Holocaust 1 Politics & Propaganda 1 Resistance 3 Responses 5 Memory 7 Violins of Hope Amnon Weinstein 9 James Grymes 10 About Violins of Hope: Instruments of Hope 10 and Liberation in Mankind’s Darkest Hour Introduction to Violin Descriptions 11 The Feivel Wininger Violin 12 The Haftel Violin 13 The Auschwitz Violin 14 Violin from Lyon, France 15 You Can Make a Difference 18 The Holocaust: A Glossary 19 Holocaust History Timeline 22 Works Cited 30 Adapted from the Violins of Hope: Teacher’s Guide to Accompany Violins of Hope Program developed by Danielle Kahane-Kaminsky, Tennessee Holocaust Commission, December 2017. Overview of Music During the Holocaust During the Holocaust, music played many different roles. From the rise of Nazi power in Germany to the end of World War II, governments and individuals used music for a variety of reasons. Here are four prominent main themes of music during Nazi Germany and the Holocaust: • Politics and Propaganda • Resistance • Responses • Memory Source: http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/ Politics & Propaganda For the Nazis, music was not only a source of national pride, but also a tool for propaganda to influence German society. They felt music had a unique significance and power to seduce and sway the masses. Shortly after the Third Reich gained power in 1933, orchestras and conservatories were nationalized and funded by the state, and popular performers were recruited to serve as propaganda outlets for the Reich. The Nazi Party made widespread use of music in its publicity, and music featured prominently at rallies and other public events. -

The Nazi Massacre of Roma in Babi Yar in Soviet and Ukrainian Historical Culture

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Baltic Worlds. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Kotljarchuk, A. (2015) Representing genocide. The Nazi massacre of Roma in Babi Yar in Soviet and Ukrainian Historical culture. Baltic Worlds, (28 maj) Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-31450 A scholarly journal from the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Södertörn University, Stockholm. search start by Andrej what's up Kotljarchuk PhD in History, Associate about Professor at the Department countries of History and Contemporary Studies at essays Södertörn University. interviews Participate in the ongoing features international project about the genocide of the Roma in reviews Ukraine during World War II elections (Foundation for Baltic and East European studies 2012- conferences 2014). Coordinating the contributors project "Soviet Nordic Minorities and Ethnic back issues Cleaning's on the Kola subscribe Peninsula" (Foundation for links Baltic and East European studies 2013-2015) and coordinator of an international network on Stalin's terrors against minorities in the Soviet Union (Swedish Institute). all Would you Roma in Babi Yar, International Roma Genocide Remembrance Day Aug. 2, 2012. Photo: Kotljarchuk. contributors like to contribute to Baltic Worlds? REPRESENTNIG Click here! GENOCDIE: ”THEN AZM I ASSACREO F ROMANI B ABY IARNI S OVEIT Follow us on ANDU KRANIAINH SITORCIAL Facebook! Like 761 CULTURE” Published on balticworlds.com on Maj 28, 2015 On March 17 , 2015, the Center for 0 comments Historical Culture at Erasmus University share Rotterdam organized the symposium ”Representing Genocide”. -

Soviet Jews in World War II Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering Borderlines: Russian and East-European Studies

SOVIET JEWS IN WORLD WAR II Fighting, Witnessing, RemembeRing Borderlines: Russian and East-European Studies Series Editor – Maxim Shrayer (Boston College) SOVIET JEWS IN WORLD WAR II Fighting, Witnessing, RemembeRing Edited by haRRiet muRav and gennady estRaikh Boston 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2014 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-313-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-61811-314-6 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-61811-391-7 (paperback) Cover design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2014 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www. academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................