Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi: Towards a Liturgical Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Perspective on Change & Growth in the Church

Historical Perspective on Change & Growth in the Church Don’t know much about history…. We are a historical people. God chose a people to make His own and from which would come a Savior. The Church was born not only out of the Jewish world of Pentecost but also out of the Greco-Roman world which believed that the Pax Romana was the final chapter. We, the Church, have been given the call to reveal the true Kingdom of Peace to a world still confident in its own power. The History of the Liturgy is the only way to glimpse the power of that Kingdom alive in each epoch, including our own. Jewish Roots—Meal and Word Passover and Seder Elements o Berakoth—classic blessings for food, land and Jerusalem o Todah—an account of God’s works and a petition that the prayers of Israel be heard o Tefillah—great intercessions o Kiddush—Holy is God o Haggadah—great narrative of salvation o Hallel—Psalms 113-118 recited at Passover Synagogue Elements o Readings from Torah, Prophets and Wisdom o Teachings o Singing of Cantor, mainly psalms Early Greco-Roman Elements—from home meal to House Church Paul and problem of agape in I Cor 11, from the 50’s o Divisions among you o Every one in haste to eat their supper, one goes hungry while another gets drunk o Institution Narrative o Whoever eats or drinks unworthily sins against the body and blood of the Lord o One should examine himself first, then eat and drink o Whoever eats or drinks without recognizing the body eats and drinks a judgment on himself o That is why so many are sick and dying o Therefore when -

The Mediation of the Church in Some Pontifical Documents Francis X

THE MEDIATION OF THE CHURCH IN SOME PONTIFICAL DOCUMENTS FRANCIS X. LAWLOR, SJ. Weston College N His recent encyclical letter, Hurnani generis, of Aug. 12, 1950, the I Holy Father reproves those who "reduce to a meaningless formula the necessity of belonging to the true Church in order to achieve eternal salvation."1 In the light of the Pope's insistence in the same encyclical letter on the ordinary, day-by-day teaching office of the Roman Pontiffs, it will be useful to select from the infra-infallible but authentic teaching of the Popes some of the abundant material touching the question of the mediatorial function of the Church in the order of salvation. The Popes, to be sure, do not speak and write after the manner of theo logians but as pastors of souls, and it is doubtless not always easy to transpose to a theological level what is contained in a pastoral docu ment and expressed in a pastoral method of approach. Yet the authentic teaching of the Popes is both a guide to, and a source of, theological thinking. The documents cited are of varying solemnity and doctrinal importance; an encyclical letter is clearly of greater magisterial value than, let us say, an occasional epistle to some prelate. It is not possible here to situate each citation in its documentary context; but the force and point of a quotation, removed from its documentary perspective, is perhaps as often lessened as augmented. Those who wish may read them in their context, if they desire a more careful appraisal of evidence. -

Mediator Dei

MEDIATOR DEI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE SACRED LITURGY TO THE VENERABLE BRETHREN, THE PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER ORDINARIES IN PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. Mediator between God and men[1] and High Priest who has gone before us into heaven, Jesus the Son of God[2] quite clearly had one aim in view when He undertook the mission of mercy which was to endow mankind with the rich blessings of supernatural grace. Sin had disturbed the right relationship between man and his Creator; the Son of God would restore it. The children of Adam were wretched heirs to the infection of original sin; He would bring them back to their heavenly Father, the primal source and final destiny of all things. For this reason He was not content, while He dwelt with us on earth, merely to give notice that redemption had begun, and to proclaim the long-awaited Kingdom of God, but gave Himself besides in prayer and sacrifice to the task of saving souls, even to the point of offering Himself, as He hung from the cross, a Victim unspotted unto God, to purify our conscience of dead works, to serve the living God.[3] Thus happily were all men summoned back from the byways leading them down to ruin and disaster, to be set squarely once again upon the path that leads to God. Thanks to the shedding of the blood of the Immaculate Lamb, now each might set about the personal task of achieving his own sanctification, so rendering to God the glory due to Him. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

A Commentary on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal

A Commentary on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal A Commentary on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal Developed under the Auspices of the Catholic Academy of Liturgy and Cosponsored by the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions Edited by Edward Foley Nathan D. Mitchell Joanne M. Pierce Foreword by the Most Reverend Donald W. Trautman, S.T.D., S.S.L. Chairman of the Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy 1993–1996, 2004–2007 A PUEBLO BOOK Liturgical Press Collegeville, Minnesota A Pueblo Book published by Liturgical Press Excerpts from the English translation of Dedication of a Church and an Altar © 1978, 1989, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. (ICEL); excerpts from the English translation of Documents on the Liturgy, 1963–1979: Conciliar, Papal, and Curial Texts © 1982, ICEL; excerpts from the English translation of Order of Christian Funerals © 1985, ICEL; excerpts from the English translation of The General Instruction of the Roman Missal © 2002, ICEL. All rights reserved. Libreria Editrice Vaticana omnia sibi vindicat iura. Sine ejusdem licentia scripto data nemini licet hunc Lectionarum from the Roman Missal in an editio iuxta typicam alteram, denuo imprimere aut aliam linguam vertere. Lectionarum from the Roman Missal in an editio iuxta typicam alteram—edition iuxta typica, Copyright 1981, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Città del Vaticano. Excerpts from documents of the Second Vatican Council are from Vatican Council II: The Basic Sixteen Documents, edited by Austin Flannery, © 1996 Costello Publishing Company, Inc. Used with permission. Cover design by David Manahan, OSB. Illustration by Frank Kacmarcik, OblSB. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. -

VENERABLE POPE PIUS XII and the 1954 MARIAN YEAR: a STUDY of HIS WRITINGS WITHIN the CONTEXT of the MARIAN DEVOTION and MARIOLOGY in the 1950S

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO In affiliation with the PONTIFICAL FACULTY OF THEOLOGY "MARIANUM" The Very Rev. Canon Matthew Rocco Mauriello VENERABLE POPE PIUS XII AND THE 1954 MARIAN YEAR: A STUDY OF HIS WRITINGS WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THE MARIAN DEVOTION AND MARIOLOGY IN THE 1950s A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology with Specialization in Mariology Director: The Rev. Thomas A. Thompson, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University ofDayton 300 College Park Dayton OH 45469-1390 2010 To The Blessed Virgin Mary, with filial love and deep gratitude for her maternal protection in my priesthood and studies. MATER MEA, FIDUCIA MEA! My Mother, my Confidence ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest gratitude to all who have helped me by their prayers and support during this project: To my parents, Anthony and Susan Mauriello and my family for their encouragement and support throughout my studies. To the Rev. Thomas Thompson, S.M. and the Rev. Johann Roten, S.M. of the International Marian Research Institute for their guidance. To the Rev. James Manning and the staff and people of St. Albert the Great Parish in Kettering, Ohio for their hospitality. To all the friends and parishioners who have prayed for me and in particular for perseverance in this project. iii Goal of the Research The year 1954 was very significant in the history of devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. A Marian Year was proclaimed by Pope Pius XII by means of the 1 encyclical Fulgens Corona , dated September 8, 1953. -

How to Read, Study and Benefit from Papal Encyclicals

How to Read, Study and Benefit from Papal Encyclicals Contents What is an Encyclical ..................................................................................................................................... 1 How to Read and Study an Encyclical ........................................................................................................... 2 Are Encyclicals Infallible Teachings of a Pope ............................................................................................... 2 History of Encyclicals ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Why Read Encyclicals if You are Not Catholic? ............................................................................................. 4 Links to Other Encyclicals and Lists of All Encyclicals ................................................................................... 4 List of Encyclicals ........................................................................................................................................... 4 What is an Encyclical The word encyclical literally means "in a circle." It is a letter intended to travel— to circulate. However in modern times it has become almost exclusively used to denote teachings from the Pope. Comparing an encyclical to other kinds of official Roman Catholic documents is a good way to understand the significance of an encyclical. Firstly, when the pope makes a declaration of some article of faith or moral law it is -

Queenship of Mary -- Queen-Mother George F

Marian Library Studies Volume 28 Article 6 1-1-2007 Queenship of Mary -- Queen-Mother George F. Kirwin Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kirwin, George F. (2007) "Queenship of Mary -- Queen-Mother," Marian Library Studies: Vol. 28, Article 6, Pages 37-320. Available at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_studies/vol28/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Studies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. George F. Kirwin, O.M.I. QUEENS HIP OF MARY - QUEEN -MOTHER TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 5 L.J .C. ET M.l. 7 CHAPTER I HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT 11 Scripture 14 Tradition And Theology 33 L~~y ~ Art M Church Teaching 61 "Ad Caeli Reginam" 78 CHAPTER II THE NATURE OF MARY's QuEENSHIP 105 Two ScHOOLS OF THOUGHT 105 De Gruyter: Mary, A Queen with Royal Power 106 M.J. Nicolas: Mary, Queen Precisely as Woman 117 Variations on a Theme 133 CHAPTER III vATICAN II: A CHANGE OF PERSPECTIVE 141 Vatican II and Mariology 141 Mary, Daughter of Sion 149 Mary and the Church 162 CHAPTER IV MARY: QuEEN-MOTHER IN SALVATION HISTORY 181 Salvation History and the Kingdo 182 The Gebirah 205 The Nature of Mary's Queenship in Light of the Queen-Mother Tradition 218 Conclusion 248 Mary as the Archetype of the Church in the History of Salvation 248 BIBLIOGRAPHY 249 Books 249 Select Marian Resources 259 International Mariological-Marian Congresses 259 Proceedings of Mariological Societies 259 National Marian Congresses 260 Specialized Marian Research/Reference Publications 260 Articles 260 Papal Documents Referenced in this Study 283 QUEENSHIP OF MARY- QUEEN-MOTHER 39 28 (2007-2008) MARIAN LIBRARY STUDIES 37-284 FOREWORD This book is the result of the collaboration of many individuals and groups who provided me with the support and encouragement I needed to bring the project to a successful conclusion. -

"In Persona Christi" Its Significance for the Theology of Ministerial

"IN PERSONA CHRISTI" ITS SIGNIFICANCE FOR THE THEOLOGY OF MINISTERIAL PRIESTHOOD IN THE DOCUMENTS OF VATICAN II by Jerome F. Thompson, B.A. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin Apr iI, 1987 Preface It was in my service as Coordinator of Hispanic Affairs for the Archdiocese of Milwaukee that I felt the need to formally work toward a degree in theology at Marquette University. The Hispanic community and the staff of the Apostolate inspired and encouraged me to undertake the task. A lot of years and a lot of work have intervened since this work was first begun. I wish to express my thanks to the Hispanic community and staff in Milwaukee for their continued personal and academic support. It am grateful to the members of the theology department of Marquette, especially Rev. William Kelly SJ and Rev. Philip J. Rossi SJ in their assistance as chairs of the department, to Rev. Richard Roach SJ, my first advisor, and Rev. Donald Keefe SJ, my final advisor, for their patience and guidance, and to Rev. Joseph Lienhard SJ and Rev. Joseph Murphy SJ who served on the reading and approval committee. I wish also to express my thanks to the officers and staff of the National Organization for the Continuing Education of Roman Catholic Clergy (NOCERCC) for whom I have worked these past five years for nudging me on and enduring my research ,and writing. Catholic Theological Union in Chicago provided a great support to me especially through its fine library resources. -

Marian Coredemption As an Impetus to Marian Devotion

Marian Coredemption as an Impetus to Marian Devotion Msgr. Arthur Burton Calkins, S.T.D. I. Introduction Marialis Cultus, the Apostolic Exhortation of the Venerable Pope Paul VI, was addressed to the Catholic Church at a crucial moment in the midst of postconciliar confusion. The optimism of Gaudium et Spes and the other conciliar documents was met head on by the turbulence of the sixties and seventies. Within ten years of the closing of the Second Vatican Council on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception in 1965 enormous societal changes were taking place, which are perhaps not even now fully assessed by the social sciences. In the course of that period, despite the fresh synthesis of Marian doctrine provided by chapter eight of Lumen Gentium, Marian devotion, which had perhaps reached its zenith in the era of the Venerable Pope Pius XII (1939-1958), seemed to have reached its nadir. The problem facing Paul VI in that debilitating milieu was how to revive Marian devotion and how to do so from the perspective of the conciliar teaching on the Blessed Virgin Mary. While the conciliar teaching had benefited from developments that had taken place in biblical, patristic, liturgical and ecclesiological studies since the First Vatican Council, it had still to convey the Church’s magisterial teaching on Our Lady, which had been handed on and enriched under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. On the one hand, the papal magisterium from the time of Blessed Pius IX onwards had continued developing the teaching about Mary’s active collaboration in the work of the redemption and Pius XI had publicly used the term “Coredemptrix” to describe this role.1 On the other hand there was a distinctive concern on the part of many to promote in the council documents language that could be more easily understood by our separated brethren. -

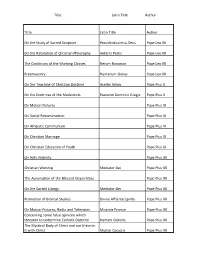

Encyclical Letters

Title Latin Title Author Title Latin Title Author On the Study of Sacred Scripture Providentissimus Deus Pope Leo XII On the Retoration of Christian Philosophy Aeterni Patris Pope Leo XII The Conditions of the Working Classes Rerum Novarum Pope Leo XII Freemasonry Humanum Genus Pope Leo XII On the Teaching of Christian Doctrine Acerbo Nimis Pope Pius X On the Doctrines of the Modernists Pascendi Dominici Gregis Pope Pius X On Motion Pictures Pope Pius XI On Social Reconstruction Pope Pius XI On Atheistic Communism Pope Pius XI On Christian Marriage Pope Pius XI On Christian Education of Youth Pope Pius XI On Holy Virginity Pope Pius XII Christian Worship Mediator Dei Pope Pius XII The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Pope Pius XII On the Sacred Liturgy Mediator Dei Pope Pius XII Promotion of Biblical Studies Divino Afflante Spiritu Pope Pius XII On Motion Pictures, Radio and Television Miranda Prorsus Pope Pius XII Concerning some false opinions which threaten to undermine Catholic Doctrine Humani Generis Pope Pius XII The Mystical Body of Christ and our Union in it with Christ Mystici Corporis Pope Pius XII Title Latin Title Author On the Appearance of the Immaculate Virgin Mary at Lourdes Pope Pius XII False Trends in Modern Teaching Pope Pius XII On the Function of the state in the Modern World Pope Pius XII Re-Evaluation of the Social Question in the light of Christian Teaching Mater et Magistra Pope John XXIII From the Beginning of Our Priesthood Sacerdotii Nostri Primordia Pope John XXIII Christianity and Social Progress Mater -

Provida Mater Ecclesia

SEOUELA ~STI IN QUESTO NUMERO Dinamismo de un carisma fundaciónal de un Instituto Secular «Vivendo in cittá greche e barbare» Maria Cristina Ventura González Nicla Spezzati L'évolution d'un charisme: A Sua Eccellenza Mons. [oáo Braz De Aviz Notre Dame du travail1905 - 2011 Prefetto C1VCSVA Nedege Védie LA PAROLA DEL SANTO PADRE The road to becoming Discorso di Sua Santitá Benedetto XVI ou r Secu lar Institute ai partecipanti alla Conferenza Naoko Ozawa Mondiale degli Istituti Secolari Apport d'un Institut Seculier Clerical Sala C1ementina, 3 febbraio 2007 aux cultures et aux Eglises d'Afrique Robert Daviaud STUDI E COMMENTI Presenza e servizio per una vita IIlaicato. Note per una riflessione evangelica in Vietnam biblico-teologica Luisa Muston Luca Mazzinghi I consigli evangelici nella secolarita ldentitá dei consacrati secolari Giorgio Mazzola Elda Geremicca - Maria RosaZamboni El camino de formación. Los Institutos Seculares a la luz La Palabra y la vida en el recorrido del itinerario histórico eclesiológico y formativo de un Instituto desde la Provida Mater Ecclesia Fernando Martín Herráez María jesús Fernández Cordero Fraternitá nel mondo: Caratteri della missione secolare uno stile evangelico nell'annuncio del Vangelo Agnese Chiara alle culture contemporanee Gianfranco Ravasi Gli Istituti Secolari nella Chiesa alga Kriiová Gli Istituti Secolari: Reste avec nous, Seigneur una forma di Vita consacrata Gérald Cyprien Lacroix nell'oggi della Chiesa Tiziano Vanzetto Una Chiesa sempre nuova Nicola Giordano Secolaritá dei Presbiteri Francesco Zenna Le Oblate Apostoliche e il Movimento Pro Sanctitate. Istituti Secolari e Movimenti ecclesiali, Storia e relazione di vita manifestazioni dello Spirito Mirella Scalia per la Chiesa di oggi.