Knjizevnost I Jezik U DSS.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroic Medievalism in from the Ancient Books by Stevan Sremac

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2020/02/02 Stefan Trajković Filipović 15 Heroic Medievalism in From the Ancient Books by Stevan Sremac In 1909, Jovan Skerlić (1877–1914), an influen- reacting against the idea of abandoning and tial Serbian literary critic, imagined a hypothetic- condemning the pre-modern times (Emery and al scenario in which people were given an op- Utz 2). In more general terms, medievalism can portunity to express their literary preferences in be observed as the (ab)use of the medieval past a public vote. “If our readership could vote to de- for modern and contemporary purposes. cide who is the greatest Serbian storyteller,” Starting from the point of view of studies in wrote Skerlić, “and whose books they like read- medievalism – a scholarly investigation into the ing the most, the most votes would without doubt presence of medieval topics in post-medieval go to Stevan Sremac” (Skerlić 23).1 A teach er by times (Müller 850; Matthews 1-10) – this paper profession, Stevan Sremac (1855–1906) wrote aims to research Sremac’s practice of medi- humorous stories and novels, for which he quick- evalism. Sremac’s medieval heroes are national ly gained popularity and fame. He could make the heroes, complementing the popular visions of whole nation laugh, argued Skerlić (ibid.). After the Middle Ages as the golden age of national his death, his fame endured and his humorous histories (Geary 15-40). Especially in the context works have been recognized as an import- of the multi-national European empires of the ant chapter in the history of Serbian literature nineteenth century, such a glorifying perspective (Deretić 1983: 397-403). -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy o f the original document. While the most advai peed technological meant to photograph and reproduce this document have been useJ the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The followini explanation o f techniques is provided to help you understand markings or pattei“ims which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target" for pages apparently lacking from die document phoiographed is “Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This| may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Wheji an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is ar indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have mo1vad during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. Wheh a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in 'sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to righj in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until com alete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, ho we ver, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "ph btographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

SERBIAN LITERATURE of the MIDDLE PERIOD (18TH – 1ST HALF of 19TH Subject CENTURY)

The title of the SERBIAN LITERATURE OF THE MIDDLE PERIOD (18TH – 1ST HALF OF 19TH subject CENTURY) Number of Subject code Subject status Semester Number of classes ECTS credits 13РСКЊСД compulsory II 4 2+1 Russian Language and L iterature and Serbian Language Study programme for which it is organised and L iterature Connection to other subjects : Medieval Serbian L iterature The subject objectives : To introdu ce students to the poetic featu res, main writers and major work s of Serbian literature of the R ennaisance, Baroque , Classicism and Pre - Romanticism; to see the status of the literature of these stylistic formations within the context of Serbian literature as a whole. Name and surname o f a professor and teaching assistant : Prof . Dusko Pevulja, PhD Danijela Jelic, MA Methods of teaching and acquiring lessons : Lectures, auditory exercises, written and oral presentations, discussions on presentations Content of the subject : Week T he middle period of Serbian literature : literary - historical context; interpretation within the most 1 relevant literary - historical synthesis Week The importance of the middle period of Serbian literature : Forms of S erbian literature revival; 2 comparison t o medieval and new lietarture Week Geopoetical, geopolitical and literary - historical contextualisation of Serbian literature during the 3 middle period of its development Week Dominant sylistic form s in Serbian literature in the m iddle period : Rennai sance, Baroque, Calssicism 4 and Pre - Romanticism Week Genesis, formation and stabilisation of genres in Serbian literature during the middle period of its 5 development Week Literary languages of Serbian literature during the middle period of its develo pment 6 Week Genres, styles and poetic features of Rennaisance and Baroque poetry 7 Week Genres, styles a nd poetic features of Classicist and Pre - Romantic poetry 8 Week Serbian historiography of Baroque/historiographic prose 9 Week Dositej Obradovi c; literary - historical status and importance; poetic, stylistic and genre features of the 1 0 work Week G. -

The Mountain Wreath by Petar Petrovic Njegos Slav

628 / RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies 2019.16 (September) A Serbian epic as a call to exterminate the “Race Betrayers”: The Mountain Wreath by Petar Petrovic Njegos / Ü. Hasanusta (p. 628-638) A Serbian epic as a call to exterminate the “Race Betrayers”: The Mountain Wreath by Petar Petrovic Njegos Ümit HASANUSTA1 APA: Hasanusta, Ü. (2019). A Serbian epic as a call to exterminate the “Race Betrayers”: The Mountain Wreath by Petar Petrovic Njegos. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (16), 628-638. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.619628 Abstract The world history witnessed a really dramatic civil war in 1990s in the Balkans. Peoples that lived together for hundreds of years experienced the most violent results of nationalist ideology with the demise of Yugoslavia. Serbs are one of the nations that involved in this civil war an in this period, their conflicts with especially Bosnian Muslims and Croats provided that the term “Serbian nationalism” is heard a lot in the world. Similarly with many other nations in history, the emergence and development of the idea of nationalism for Serbs started in 19th century. Serbs, who lived under the rule of empires, especially the Ottoman Empire, carried out the first rebellion against the Ottomans in 1804 and in this period, Serbian intellectuals were also attempting to create a national consciousness at the same time. These attempts to create a national language and literature would help this consciousness to improve and they would show their effect in that time and in the following century, as well. Even in the fall of Yugoslavia, the effect of this national mythology developed as a result of these efforts is seen clearly. -

BCS - Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian 1

BCS - Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian 1 BCS - BOSNIAN-CROATIAN- SERBIAN BCS Class Schedule (https://courses.illinois.edu/schedule/DEFAULT/ DEFAULT/BCS/) Courses BCS 101 First Year Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian I credit: 4 Hours. (https://courses.illinois.edu/schedule/terms/BCS/101/) Oral and written work on pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary. For students with no previous study of Bosnian, Croatian or Serbian. BCS 102 First Year Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian II credit: 4 Hours. (https://courses.illinois.edu/schedule/terms/BCS/102/) Continuation of BCS 101. Prerequisite: BCS 101 or equivalent proficiency. BCS 115 South Slavic Cultures credit: 3 Hours. (https:// courses.illinois.edu/schedule/terms/BCS/115/) Exploration of South Slavic cultures in the historically rich and complex region sometimes referred to as "the Balkans," focusing particularly on those groups found within the successor states of the former Yugoslavia. Critical look at the traditional view of the region as the crossroads or the bridge between East and West, and at the term Balkanization which has become a pejorative term used to characterize fragmented, and self- defeating social systems. This course satisfies the General Education Criteria for: Cultural Studies - Non-West Social Beh Sci - Soc Sci BCS 199 Undergraduate Open Seminar credit: 1 to 5 Hours. (https:// courses.illinois.edu/schedule/terms/BCS/199/) May be repeated. BCS 201 Second Year Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian I credit: 4 Hours. (https://courses.illinois.edu/schedule/terms/BCS/201/) Completion of grammar; written and oral exercises aimed at active command of the language. Prerequisite: BCS 102 or equivalent proficiency. BCS 202 Second Year Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian II credit: 4 Hours. -

The Magic of Belgrade – a City Where Heritage Meets the Modern1

The Magic of Belgrade – A City Where Heritage Meets the Modern1 Ljiljana Markovic, University of Belgrade, Serbia Biljana Djoric Francuski, University of Belgrade, Serbia Bosko Francuski, University of Belgrade, Serbia The IAFOR Conference on Heritage & the City – New York 2018 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The capital of Serbia, Belgrade, is a city with a lengthy history dating back to the seventh millennium BC. In the third century BC the Celts named it Singidunum, whereas since the ninth century AD it has been known as Beligrad, meaning The White City. Strategically located on the crossroad between the Occident and the Orient, between the Pannonian Valley and the Balkans, at the confluence of the Danube and the Sava River, this city, in which heritage meets the modern, is also the meeting point of influences from West and East. The city has been depicted by many authors, both Serbian and foreign, but among these literary works stands out the oeuvre of Momo Kapor, who devoted his whole life to writing about and painting scenes of life in Belgrade. Kapor was well known and successful both as a painter, having exhibited his work in renowned galleries in Serbia and abroad, and as a writer, since his forty-odd novels and short story collections are bestsellers in Serbia and have been translated into dozens of foreign languages. In The Magic of Belgrade, Momo Kapor does not only describe the monuments and people of this beautiful city, he even searches for what he calls ‘the spirit of Belgrade’. The purpose of this paper is to pinpoint such elements of Kapor’s work that capture the spirit of the place by reflecting, on the one hand, its heritage and, on the other, its urban growth which has resulted in its modernity. -

On the Oriental Lexicon in the Serbian Language1

Chapter 3: Lexicon as Evidence of the East-West Interaction On the Oriental Lexicon in the Serbian Language1 Prvoslav Radić Abstract Although the links between the Serbian and Oriental languages date back far in history, they distinctly marked the period of Ottoman domination in the Balkans, i.e. the period since the 14th century. The most abundant Turkish linguistic traces have remained along the main strategic lines of Ottoman expansion (Thrace—Macedonia—south Serbia—the Raška region—Bosnia and Herzegovina); migrations of the Serb population contributed to their wide reach by disseminating Turkish loanwords far from central Balkan areas. The contacts between the Serbian and Turkish languages occurred in a broad sociolinguistic range dictated by Ottoman conquerors (terminology related to state administration, army, judicial system, commerce, cookery, etc.). Key words: Serbian language, orientalisms, balkanization, standardi- zation, purism. 1 This study was presented at the SRC-FFUB Joint Workshop on Serbian Linguistics (“The Serbian Language as Viewed by the East and the West: Syn- chrony, Diachrony and Typology”) organized by the Slavic Research Centre, Hokkaido University and the Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade, on February 5, 2014, in Sapporo. In this paper, the term ‘Serbian’ refers to the lan- guage spoken by the Serbs in all South Slavic and Balkan territories no matter where they live (cf. the semantic distinction in Serbian between the terms ‘srp- ski’ and ‘srbijanski’). - 133 - Prvoslav radić I. On Ancient Linguistic Links with Turanian Peoples It is a well-known fact that the Slavs have gravitated towards the East and the peoples of the East from the earliest times. -

Complete Issue

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 6 May-October 1991 Number 2-3 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley David Henderson J. Chris Womack Whitney A. Womack Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1991 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

Hailing the Serbian “People”

HAILING THE SERBIAN “PEOPLE”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE CENTRAL ROLE OF THE KOSOVO MYTH IN THE CONSTITUTION OF SERBIAN ETHNO-NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE NORMALIZATION OF VIOLENCE IN THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA by CHRISTINA M. MORUS (Under the Direction of Kevin DeLuca) ABSTRACT Throughout the fifty years in which Josip Broz Tito was the leader of Yugoslavia, ethnic tensions had been nearly non-existent. Throughout the region, Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks had shared the same schools, places of employment and residences, and had a common language. For the most part, people’s ethnic and religious identities were subordinate to their identity as Yugoslavs. Yet, by the end of the 1980s, ethno-national consciousness became a part of the daily lives of many Yugoslav people. For this to be possible, peoples’ Yugoslav identity had to become tertiary. This project examines the role of rhetoric in discounting the pan-Slavic identity among Serbs and in constituting an exclusive, racialized, and highly politicized Serbian people in its place. I critique the rhetorical strategies of Serbian cultural elites and analyze the public discourse of Slobodan Milosevic with an eye to the ways in which politics and culture worked in conjunction toward a common end. In doing so I posit the effects of constitutive discourses on the polarizing national identities that rapidly replaced the largely unified Yugoslav identity, thereby legitimizing the mass violence that characterized the break-up of the Yugoslav Federation. Through essential discourses of historic victimization, the way in which Serb identity was situated in relation to Yugoslavia and the rest of the world at large was increasingly polarizing. -

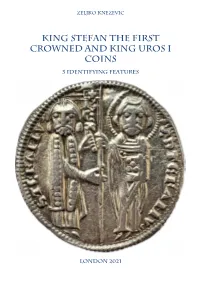

King Stefan the First Crowned and King Uros I Coins

Zeljko Knezevic King Stefan The First Crowned and King Uros I coins 5 identifying features London 2021 These 5 identifying features are: 1. Weight. 2.178g +/- 1% 2. Size 20-21mm 3. Moneyer mark 4. Line across the top of the throne 5. Decorative letters We have 2 types of Serbian medieval coins with matching features above. First type has description STEFANV REX SSTEFANV (STEFAN KING SAINT STEFAN) and second type has description VROSIV REX SSTEFANV (UROS KING SAINT STEFAN). Miroslav Jovanovic in his book “Srpski Srednjovekovni Novac” catalogue 2012 page 11 claims that there were two Serbian medieval coin hordes found. Earlier one is so called Tetovo Hoard which only included first type coins with description STEFANV REX SSTEFANV (STEFAN KING SAINT STEFAN). Second later one so called Veron Hoard included both types. This makes us conclude that STEFANV REX SSTEFANV type precedes and its older then VROSIV REX SSTEFANV type. Following document has been published in Monumenta Serbica spectantia historiam Serbiae Bosnae Ragusii book by F Miklosich in Vienna 1858 page 71. First line reads: “Стефанb Оурошb, по милости вожиIεи кралb, оуноукb господина ми кралIa Стефана, синb господина ми кралIa Оуроша, ...” “Stefan Uros, in god’s grace king, grandson of my lord the king Stefan, son of my lord the king Uros, ...” Following document is from Serbian Royal Documents at the State Archives in Dubrovnik. Written in 1306 by king Stefan Uros II Milutin Nemanjić who grants to the monastery on the island of Mljet possessions in the vicinity of Dubrovnik and various privileges. At the bottom of the document between two lines of the signature of the king, king states: “Стефанb Оурошb, по мнлостн вжнIεн кра, оуноукb гнамн кра Стефана, синb гнамн кра Оуроша, ...” “Stefan Uros, in god’s grace king, grandson of our king Stefan, son of our king Uros, ...” In both documents king Stefan Uros II Milutin Nemanjić (1282–1321) identifies his grandfather as Stefan and his father as Uros. -

An Introduction to Serbian Literature

An Introduction to Serbian Literature Serbian literature is a branch of the large tree that grew on the rocky and often bloody Balkan Peninsula during the last millennium. Its initial impulse came from the introduction of Christianity in the ninth century among the pagan Slavic tribes, which had descended from the common-Slavic lands in Eastern Europe. The first written document, the beautifully ornamented Miroslav Gospel, is from the twelfth century. Not surprisingly, the first written litera- ture was not only closely connected with the church but was practically in- spired, created, and developed by ecclesiastics—the only intellectuals at the time. As the fledgling Serbian state grew and eventually became the Balkans’ mightiest empire during Tsar Du‰an’s reign in the first half of the fourteenth century, so did Serbian literature grow, although at a slower pace. From the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries it blossomed, suddenly but genuinely, in the form of the now famous old Serbian biographies of rulers of state and church. Until modern times, this brilliance was equaled only by the literature of the medieval republic of Dubrovnik. Then came the Turkish invasion, and a night, four centuries long, descended upon Serbia and every aspect of its life. The literary activity in the entire area during those dark ages was either driven underground or interrupted altogether. The only possible form of litera- ture was oral. Consisting of epic poems, lyric songs, folk tales, proverbs, co- nundrums, etc., it murmured like an underground current for centuries until it was brought to light at the beginning of the nineteenth century. -

The Legend of Kosovo

Oral Tradition, 6/2 3 (1991):253-265 The Legend of Kosovo Jelka Ređep The two greatest legends of the Serbs are those about Kosovo and Marko Kraljević. Many different views have been advanced about the creation of the legend of Prince Lazar and Kosovo (Ređep 1976:161). The most noteworthy, however, are those of Dragutin Kostić (1936) and Nikola Banašević (1935). According to Banašević, the legends of Marko Kraljević and Kosovo sprang up under the infl uence of French chansons de geste. Kostić, however, takes a different stance. Rejecting Banašević’s interpretation along with the opinion that the legend of Kosovo arose and took poetic form in the western regions of Yugoslavia, which in the second half of the fi fteenth century had strong ties with western Europe and in which the struggle against the Turks was most intense, Kostić points out that Banašević does not distinguish between the legend and its poetic expression in the Kosovo poems. He states that “French chivalric epics did not affect the formation and even less the creation of the fi rst poem about Kosovo, not to mention the legend of Kosovo, but only modifi ed the already created and formed legend and its fi rst poetic manifestations” (1936:200; emphasis in original). It seems reasonable to accept Kostić’s opinion that the legend originated in the region in which the battle of Kosovo took place. The dramatic nature of the event itself, along with those that followed, could certainly have given rise to the beginnings of the legend soon after the Serbian defeat at Kosovo on June 15, 1389 (June 28 of the old calendar), and the canonization of Prince Lazar.