Success Stories in Plant Based Classroom Curriculum Development Colon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 BOC Yearbook.Pub

The British Orchid Council Year Book 2018 A Guide for Orchid Enthusiasts 50p or more 50p or more Donation- 1 - Please The British Orchid Council Registered Charity 1002945 President Mr Max Hopkinson 5 Golf Road, Radcliffe on Trent, Nottingham NG12 2GA Tel: 0115 9123095 Email: [email protected] Chairman Mr Arthur Deakin Pomarium Cottage Back Lane, Hallam, Notts. NG22 8AG Tel: 01636 819974 Email: [email protected] Vice Chairman Vacant Hon. Secretary Mrs Pat McLean 3 Springfield Avenue, Eighton Banks, Gateshead NE9 7HL Tel: 0191 4879515 Email: [email protected] Hon. Treasurer Mr Bob Orrick 1 Hazelmere Close, Billingham, Teesside TS22 5RQ Tel: 01642 554149 Email: [email protected] Minutes Secretary Mrs Thelma Orrick 1 Hazelmere Close, Billingham, Teesside TS22 5RQ Tel: 01642 554149 Email: [email protected] Handbook Contents 1.- 3 About BOC 6 - 12 Culture Sheets 13 - 16 Pests and diseases 20 - 22 British Orchid Nurseries 23 - 26 Diary of Events 31.– 27 BOC Judging Symposiums, RHS Orchid Committee meetings 30 - 37 Members of the BOC 31.– 38 National Collections of Orchid 39 - 40 BOC Photographic Competition 2016 /17. The winner is shown on the front cover, details below, and the runner up is on page 26. Editors: Chris Barker. Email: [email protected] & Iain Wright. Email: [email protected] Front cover Dactylorhiza incarnata , Ivar Edvinsen , Hardy Orchid Society. st 1 place in the BOC Photographic Competition - 2 - Welcome Hi everyone, welcome to this edition of the British Orchid Council Yearbook. I hope that you find it enjoyable and informative. If you have any suggestions for changes or improvements to future editions please let me know. -

RHS Recommended Gardens

Recommended Gardens Selected by the RHS for 2010 www.rhs.org.uk A GUIDE TO FREE ACCESS FOR RHS MEMBERS The RHS, the UK’s leading gardening charity Contents Frequently RHS Gardens Asked Questions www.rhs.org.uk/gardens 3 Frequently Asked Questions As well as the four RHS – ❋ ❋ owned gardens (Wisley, RHS Garden Harlow Carr RHS Garden Hyde Hall Crag Lane, Harrogate, North Yorkshire Buckhatch Lane, Rettendon, Chelmsford, Hyde Hall, Harlow Carr and 3 RHS Gardens HG3 1QB Tel: 01423 565418 Essex CM3 8AT Tel: 01245 400256 Rosemoor), the RHS has 4 Recommended Gardens for 2010 teamed up with 147 Joint Member 1 gardens around the UK and 6 Scotland Membership No 12345678 23 overseas independently © RHS 12 North West owned gardens which are Mr A Joint generously offering free 15 North East access to RHS Members Expires End Jul-10 © RHS / Jerry Harpur (one member per policy), 20 East Anglia either throughout their * opening season or at Completely in tune with its Yorkshire RHS Garden Hyde Hall provides an oasis 23 South East selected periods. setting, Harlow Carr embodies the of peace and tranquillity with sweeping 31 South West For a full list tick ‘free access for RHS Members’ rugged honesty of its host region panoramas, big open skies and far on www.rhs.org.uk/rhsgardenfinder/gardenfinder.asp whilst championing environmental reaching views. The 360-acre estate 39 Central awareness and sustainability. integrates fluidly into the surrounding Dominated by water, stone and farmland, meadows and woodland, 46 Wales How are the gardens chosen? woodland, its innovative design and providing a gateway to the countryside Who can gain free entry? Whether formal landscape, late creative planting provide a beautiful where you can watch the changing ✔ RHS members with an asterisk 50 Northern Ireland season borders or woodland, all and tranquil place for meeting friends, seasons and get closer to nature. -

2021 Rhs Forward Planner

2021 RHS FORWARD PLANNER Please note, these activities are subject to change at any time. For full, up-to-date events listings at the RHS gardens, please visit www.rhs.org.uk/gardens or contact the RHS Press Office on [email protected] Date Event Location Description Key Contact January Jan 16 – Feb Japanese RHS Garden A fascinating exhibition that charts the history Caroline Jones 14 Exhibition and Pop- Harlow Carr of the Kimono and explores the symbolism of [email protected] Up Shop – The this traditional garment within Japanese culture History of the Kimono TBC RHS Community Nationwide Details announced about the RHS Community Claire Weaver Awards announced Awards (running in place of the RHS Britain in [email protected] Bloom finals competition in 2021) February Feb 8 -14 National All gardens Shining a light on the RHS apprenticeship Claire Weaver Apprenticeship scheme and wide range of horticultural career [email protected] Week opportunities Feb 12 – 14 Early Spring Show RHS Garden Now in its third year at the RHS Garden Hyde Caroline Jones Hyde Hall Hall, expect to find inspiring displays of [email protected] beautiful and unusual early spring-flowering bulbs and plants to buy from some of the country’s top growers and nurseries Feb 13- 21 February half term All gardens All-weather family-friendly half term activities Caroline Jones (dates vary by activities across the RHS Gardens [email protected] garden) 1 TBC RHS Pest and Nationwide RHS announces the top pests and diseases Laura Scruby Disease -

Changing Society

Growing the RHS Changing society The RHS is evolving at a faster pace than ever before. How is Sue Biggs, Director General, inspiring the Society – and the nation – to grow? Author: James Alexander-Sinclair, garden designer and member of RHS Council. Photography: Paul Debois n the Return of Sherlock Holmes our hero wakes Watson in the middle of the night. ‘Come, Watson, I come!’ he cries. ‘The game is afoot.’ The same could be said of the Royal Horticultural Society. There are all sorts of things going on – those who have been to any of the four RHS Gardens recently (or read this magazine over the last year or so) do not need to be as perspicacious as Sherlock Holmes to have noticed that there are diggers and people in hi-viz vests cluttering up some of the usually peaceful RHS Director pathways. There are gaps where buildings once stood Sharing our knowledge General Sue Biggs and new shiny edifces are popping up in their place. The question is, of course, ‘why’? It seemed sensible talks to James So what exactly is going on? It is not just at RHS to seek this answer straight from Sue Biggs, RHS Alexander-Sinclair. Garden Wisley – there has been change happening Director General, who has been the driving force at Harlow Carr, Hyde Hall, Rosemoor and, of course, behind this initiative. We began by talking about at Bridgewater in Salford where the Society’s new Wisley where there is to be a new Welcome Building ffth garden is under development. It seems that opening next March. -

Delgdecisions160719.Pdf

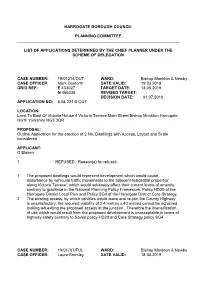

HARROGATE BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE LIST OF APPLICATIONS DETERMINED BY THE CHIEF PLANNER UNDER THE SCHEME OF DELEGATION CASE NUMBER: 19/01214/OUT WARD: Bishop Monkton & Newby CASE OFFICER: Mark Danforth DATE VALID: 19.03.2019 GRID REF: E 433027 TARGET DATE: 14.05.2019 N 466336 REVISED TARGET: DECISION DATE: 01.07.2019 APPLICATION NO: 6.54.221.B.OUT LOCATION: Land To East Of Victoria House 4 Victoria Terrace Main Street Bishop Monkton Harrogate North Yorkshire HG3 3QR PROPOSAL: Outline Application for the erection of 2 No. Dwellings with Access, Layout and Scale considered. APPLICANT: G Blaken 1 REFUSED. Reason(s) for refusal:- 1 The proposed dwellings would represent development which would cause disturbance by vehicular traffic movements to the adjacent residential propertys' along Victoria Terrace', which would adversely affect their current levels of amenity, contrary to guidance in the National Planning Policy Framework, Policy HD20 of the Harrogate District Local Plan and Policy SG4 of the Harrogate District Core Strategy. 2 The existing access, by which vehicles would leave and re-join the County Highway is unsatisfactory, the required visibility of 2.4 metres x 40 metres cannot be achieved looking left exiting the proposed access at the junction. Therefore the intensification of use which would result from the proposed development is unacceptable in terms of highway safety contrary to Saved policy HD20 and Core Strategy policy SG4. CASE NUMBER: 19/01707/FUL WARD: Bishop Monkton & Newby CASE OFFICER: Laura Bromley DATE VALID: 18.04.2019 GRID REF: E 432518 TARGET DATE: 13.06.2019 N 466469 REVISED TARGET: DECISION DATE: 13.06.2019 APPLICATION NO: 6.54.279.FUL LOCATION: Markenfield House 6 Harvest View Bishop Monkton Harrogate North Yorkshire HG3 3TN PROPOSAL: Erection of a sunlounge. -

Downloading Onto the Group’S Database at the R.B.G., Healthy, Fat, Expectant C

Bulletin 109 / July 2012 / www.rhodogroup-rhs.org Chairman’s NOTES Chairman’s Report to the AGM Andy Simons - Chairman 30th May 2012 here are surely fewer more dispiriting things than to have concluded a difficult and complex task only to discover T that your work was actually nugatory and that it will need to be conducted again with a revised set of guidelines and constraints; unfortunately this is exactly the situation that the Rhododendron, Camellia & Magnolia Group and I find ourselves in. As you will be aware from my briefing at last year’s AGM we concluded the process of refreshing the group’s constitution and getting the Council of the RHS to agree its contents; however you will also recall that the group’s relationship to the original Rhododendron and Camellia Plant Sub-Committee was still being worked on and that the RHS was continuing a review of its governance and that of all its committees. I am unclear if the analysis of its governance or some other financial or legal Rhododendron ‘Mrs Furnivall’ Photographed at the AGM 30th May 2012. review caused the RHS to reconsider its position with respect (Caucasicum hybrid x R. griffithianum – Waterer, pre-1930) to the RCM Group; however it has been regrettably necessary From the Group’s Collection of ‘Hardy Hybrids’ growing at ‘Ramster,’ for the RHS to do so. What is clear so far is that the existing Chiddingfold, Surrey’ - where the Annual General Meeting was held. RCM Group constitution cannot be supported by the RHS in This paper is likely to put forward 2 broad alternatives: the longer term; it is non-compliant with the society’s legal and either greater integration within the RHS with a resulting financial obligations as a national charity. -

Uk Holiday Collection

UK HOLIDAY COLLECTION FLEXIBLE HOLIDAY BOOKINGS TRANSFER FOR FREE IF YOU CHANGE YOUR MIND (2021 HOLIDAYS) How to book Once you’ve finished browsing these pages at your leisure and when you’re ready to treat yourself to a place on one of our holidays, just get in touch and we’ll do the rest! Give our friendly sales team a call, Monday to Friday between 9am and 6pm, on 01334 611 828. Alternatively, send us an email at [email protected] For further details on any of the trips mentioned, including information on our day-by-day itineraries or full booking conditions, please visit our website: www.brightwaterholidays.com Finally, if you have any questions, do feel free to get in touch with our customer care team on 01334 845530. Happy browsing, and we look forward to hearing from you! LOOKING FORWARD he recent news that travel is back on for 2021 was very welcome and we can’t wait to T do what we love most – take people on holiday! One of the best parts of any travel experience is the anticipation. We love sitting down with a cup of tea to look at brochures, browsing itineraries and seeing what takes our fancy – and how we’ve missed it! So now the time has come to finally start turning our holiday dreams into reality, we thought you would appreciate a brochure to help get you on your way. We understand that while there might still be some reluctance to travel overseas, there is a huge demand for holidays within the British Isles, which is why on the following pages you will find a great selection of our UK and Irish holidays, which have always formed a large Full financial part of our programme and have been extended even further. -

Citizen Science, Plant Species, and Communities' Diversity and Conservation on a Mediterranean Biosphere Reserve

sustainability Article Citizen Science, Plant Species, and Communities’ Diversity and Conservation on a Mediterranean Biosphere Reserve Maria Panitsa 1,* , Nikolia Iliopoulou 2 and Emmanouil Petrakis 2 1 Department of Biology, Division of Plant Biology, University of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece 2 Arsakeio Lyceum of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece; [email protected] (N.I.); [email protected] (E.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Citizen science can serve as a tool to address environmental and conservation issues. In the framework of Erasmus+ project CS4ESD, this study focuses on promoting the importance of plants and plant species and communities’ diversity by using available web-based information because of Covid-19 limitations and concerning the case study of Olympus mountain Biosphere Reserve (Greece). A questionnaire was designed to collect the necessary information, aiming to investigate pupils’ and students’ willing to distinguish and learn more about plant species and communities and evaluate information found on the web. Pupils, students, and experts participated in this study. The results are indicative of young citizens’ ability to evaluate environmental issues. They often underestimate plant species richness, endemism, plant communities, the importance of plants, and ecosystem services. They also use environmental or plant-based websites and online available data in a significantly different way than experts. The age of the young citizens is a factor that may affect the quality of data. The essential issue of recognizing the importance of plants and Citation: Panitsa, M.; Iliopoulou, N.; plant communities and of assisting for their conservation is highlighted. Education for sustainable Petrakis, E. Citizen Science, Plant development is one of the most important tools that facilitates environmental knowledge and Species, and Communities’ Diversity enhances awareness. -

Information Leaflet for RHS Garden Rosemoor

GARDEN OPENING TIMES WEDDINGS AT ROSEMOOR WELCOME TO Rosemoor Garden is open every day except for Christmas Day. If you are thinking of getting married in Devon, it would be difficult to find RHS GARDEN ROSEMOOR April to September 10am – 6pm a more romantic wedding venue than Rosemoor. October to March 10am – 5pm You can exchange your vows in one of eight romantic locations throughout In 1988 Lady Anne Berry donated her RHS Garden Rosemoor the garden which have been licensed to hold wedding ceremonies. All have Great Torrington, Devon EX38 8PH their own unique charm, and some are the closest you can get to being Sharing the best in Gardening eight acre garden to the Royal Horticultural married outside in this country. Toast your marriage with Champagne Society together with a further 32 acres Tel: 0845 265 8072 on the sunny terrace, and then celebrate with a delightful reception for up to 250 guests in our stunning marquee. The Garden Restaurant, outside of pastureland. seating area and Winter Garden Lawn can also be incorporated to accommodate guests for an evening party. Tel: 01805 626800 Now Rosemoor boasts an impressive 65 acres of enchanting and inspirational RHS GARDEN garden and woodlands, which provide year-round interest for everyone to enjoy. Welcome to Rosemoor, a garden for all the senses. ROSEMOOR PLANT LABELS JOIN TODAY STAY AT ROSEMOOR FREE The plants at Rosemoor are labelled with their botanical (Latin) names. We do Do you love Rosemoor? Then why not stay a while? Our comfortable ENTRY not use common names for a number of reasons. -

A Case for Renaming Plant Blindness

Received: 14 July 2020 | Revised: 21 August 2020 | Accepted: 24 August 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ppp3.10153 BRIEF REPORT Plant awareness disparity: A case for renaming plant blindness Kathryn M. Parsley Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Memphis, Societal Impact Statement Memphis, TN, USA “Plant blindness” is the cause of several problems that have plagued botany outreach Correspondence and education for over a hundred years. The general public largely does not notice Kathryn M. Parsley, Department of plants in their environment and therefore do not appreciate how important they Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, are to the biosphere and society. Recently, concerns have been raised that the term TN 38152, USA. “plant blindness” is problematic due to the fact that it is a disability metaphor and Email: [email protected] equates a disability with a negative trait. In this Brief Report, I place the term “plant blindness” into historical context through a short literature review on the subject and follow this with why the term has been criticized for its ableism. I then propose a more appropriate term to replace plant blindness: plant awareness disparity (PAD) and explain why it both addresses the problems with “plant blindness” while keeping the original reasoning behind the term intact. KEYWORDS botany education, botany outreach, plant blindness, plant conservation, plants and society, plants and well-being, plants versus animals 1 | INTRODUCTION the erroneous conclusion that they are unworthy of human consid- eration” (Wandersee & Schussler, 1999, 2001). For over a hundred years, botanists and educators alike have The term was rooted in both botany education research and lit- lamented the disparities in attention toward plants and animals. -

Gardens of England

11 Days/10 Nights Departs Daily Gardens of England: London, Cotswolds, Lake District & York England is truly a nation of garden lovers with more English gardens open to the public than anywhere else in the world. For many keen gardeners, a visit to an English garden is one of the highlights of any trip to the UK. This garden-filled tour is perfect for gardeners and as well as those who just enjoy viewing them. You will visit two of the RHS (Royal Horticultural Society) Gardens, Garden Wisley and Garden Harlow Carr, plus elegant Kew Gardens, the Blenheim and Kensington Palace gardens. Your package includes non-stop flights on Delta, and your Oyster Card makes it easy to visit some of London's famous landmarks. In addition to the stunning gardens, you will enjoy full days exploring beautiful countryside, historic towns and some of the picturesque villages of England; all at your own pace. ACCOMMODATIONS • 2 Nights London • 2 Nights Lake District • 2 Nights London • 2 Nights Cotswolds • 2 Nights York INCLUSIONS • Private Arrival Transfer • Entrance to Blenheim Palace, • Entrance to Kensington Palace • London TripBuilder Guidebook Park and Gardens and Gardens • London Oyster Card • Ullswater Lake Cruise • Private Departure Transfer • Entrance to Kew Gardens • Entrance to Lowther Castle and • 7-Day Compact Manual Car • Entrance and Private Guided Gardens Rental with CDW Garden Tour at RHS Garden • Wisley Entrance and Private Guided • Daily Breakfast • Garden Tour at RHS Garden Harlow Carr • ARRIVE LONDON: Meet your driver in the arrival hall for your private transfer to a centrally located hotel. The remainder of the day is at your leisure. -

Grass Blindness Thomas, Howard

Aberystwyth University Grass blindness Thomas, Howard Published in: Plants, People, Planet DOI: 10.1002/ppp3.28 Publication date: 2019 Citation for published version (APA): Thomas, H. (2019). Grass blindness. Plants, People, Planet, 1(3), 197-203. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.28 Document License CC BY General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 DOI: 10.1002/ppp3.28 RESEARCH ARTICLE Grass blindness Howard Thomas IBERS, Aberystwyth University, Ceredigion, UK Societal Impact Statement Lolium temulentum (darnel) is an almost‐forgotten species that combines the charac‐ Correspondence Howard Thomas, IBERS, Aberystwyth teristics of a weed, a pasture grass, a cereal, a medicinal herb, a hallucinogen, a reli‐ University, Ceredigion, UK. gious symbol, and a literary trope. The way in which darnel has disappeared from Email: [email protected] common experience and memory, particularly in the developed world, has lessons to teach about how passive and active influences can conspire to render people blind to the cultural significance of historically important plants.