Infant Mortality Rates for Farming and Unemployed Households

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Cultural Study About Cyborg Market Acceptance: Japan Versus Spain

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Murata, Kiyoshi; Arias-Oliva, Mario; Pelegrín-Borondo, Jorge Article Cross-cultural study about cyborg market acceptance: Japan versus Spain European Research on Management and Business Economics (ERMBE) Provided in Cooperation with: European Academy of Management and Business Economics (AEDEM), Vigo (Pontevedra) Suggested Citation: Murata, Kiyoshi; Arias-Oliva, Mario; Pelegrín-Borondo, Jorge (2019) : Cross-cultural study about cyborg market acceptance: Japan versus Spain, European Research on Management and Business Economics (ERMBE), ISSN 2444-8834, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 25, Iss. 3, pp. 129-137, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2019.07.003 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/205798 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Pdf: 660 Kb / 236

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 23, 2017 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2017 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Nobukazu Takano Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Japan and the UK

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford Freedom of Information Legislation and Application: Japan and the UK By Satoshi Kusakabe Michaelmas Term 2016/Hilary and Trinity Terms 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 1 1. Introduction 2 2. Literature review 2.1 Existing research on FOI and journalism in Japan and the UK 5 3. Media analysis 3.1 How often have journalists used FOI in Japan and the UK? 8 4. Case studies in Japan 4.1 Overview of the FOI legislation 12 4.2 Misuse of public expenses by Tokyo Governors 13 4.3 Misuse of disaster reconstruction money 15 4.4 Government letters to the US military 17 5. Case studies in the UK 5.1 Overview of the FOI legislation 19 5.2 MPs’ expenses scandal 23 5.3 Prince Charles’s letters 25 5.4 The Government’s Failed attempt to water down FOI 27 5.5 National security vs. FOI 28 5.6 A powerful tool for local journalists 30 6. Challenges of FOI for journalism 6.1 Lazy journalism? 32 6.2 Less recording and the “chilling effect” 34 6.3 Delay and redaction 36 7. Conclusions and recommendations 38 Bibliography 40 Appendix 42 Acknowledgements The nine months I spent in Oxford must be one of the most exciting and fulfilling periods in my career. This precious experience has definitely paved a new way for me to develop my career as a journalist. I would like to express my deepest and most sincere gratitude to the following: The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism for giving me the opportunity to conduct this research, and my supervisor Chris Westcott for giving me a lot of kind advice and intellectual insights; also James Painter, David Levy and all the staff for providing great academic and administrative support. -

Japan Labor Review Volume 14, Number 1, Winter 2017

ISSN 1348-9364 J a p an L a b o r R Japan e v i e w Volume 14, Volume LaborVolume 14, Number R 1,e Winterv 20i17ew Number 1, Winter 2017 Number 1, Winter Special Edition Combining Work and Family Care Articles Current Situation and Problems of Legislation on Long-Term Care in Japan’s Super-Aging Society Kimiyoshi Inamori Family Care Leave and Job Quitting Due to Caregiving: Focus on the Need for Long-Term Leave Shingou Ikeda The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training Choices of Leave When Caring for Family Members: What Is the Best System for Balancing Family Care with Employment? Mayumi Nishimoto Frameworks for Balancing Work and Long-Term Care Duties, and Support Needed from Enterprises Yoko Yajima Current Issues regarding Family Caregiving and Gender Equality in Japan: Male Caregivers and the Interplay between Caregiving and Masculinities Mao Saito Article Based on Research Report Job Creation after Catastrophic Events: Lessons from the Emergency Job Creation Program after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Shingo Nagamatsu, Akiko Ono JILPT Research Activities The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kazuo Sugeno, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training EDITORIAL BOARD Tamayu Fukamachi, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training Hiromi Hara, Japan Women’s University Yukie Hori, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training Shingou Ikeda, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training Minako Konno, Tokyo Woman’s Christian University Yuichiro Mizumachi, Tokyo University Hiroshi Ono, Hitotsubashi University Tadashi Sakai, Hosei University Hiromi Sakazume, Hosei University Masaru Sasaki, Osaka University Tomoyuki Shimanuki, Hitotsubashi University Hisashi Takeuchi, Waseda University Mitsuru Yamashita, Meiji University The Japan Labor Review is published quarterly in Spring (April), Summer (July), Autumn (October), and Winter (January) by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. -

The Cold War and Japan's Postcolonial Power in Asia

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at https://www.neh.gov/grants/research/fellowships-advanced-social-science- research-japan for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Engineering Asian Development: The Cold War and Japan's Post- Colonial Power in Asia Institution: Arizona State University Project Director: Aaron S. Moore Grant Program: Fellowships for Advanced Social Science Research on Japan 400 Seventh Street, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov 1 Research Statement (Aaron S. Moore) Engineering Asian Development: The Cold War and Japanese Post-Colonial Power in Asia Japan was the first non-Western nation to transform its status from a semi-developed country to a major donor to the development of other countries. -

30 Years of Industrial Cooperation Responding To

EU-JAPAN NEWS DECEMBER 2016 I 4 VOL 14 30 YEARS OF INDUSTRIAL COOPERATION RESPONDING TO THE CHANGING NEEDS As the end of the year 2016 approaches, we ready ourselves for the year 2017 which represents a major milestone for the EU-Japan Centre: our 30th Anniversary. For the past three decades, the EU-Japan Centre has played a significant role as a bridge between Europe and Japan. In relative numbers, since its creation in 1987, the Centre has produced over 2,500 graduates of its managerial courses (including the Lean/Kaizen missions) in Japan and Europe, 900 alumni of the Vulcanus programme, 25,000 participants in 300 policy seminars and over 200 analytical reports and webinars. We believe the Centre remains as relevant as it was back in 1987, since Japan continues to be a key market and partner for Europe and vice versa. In the same context, the “joint venture” (European Commission/Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan) characteristic of the Centre still bears a substantial “win-win” symbolic significance. This particularity makes the Centre a unique benchmark amongst other business support initiatives established more recently in Asia and Europe. Nevertheless, we are well aware that we cannot live exclusively on the back of our heritage and the Centre has to continuously evolve, expand and calibrate its mission to the present and future needs of the EU and Japanese industrial and business communities, particularly in the new era to be opened with the likely conclusion of an FTA/EPA. SMEs AT THE CORE OF OUR ACTIVITIES With this in mind, in the last five years we have placed the support for SMEs at the core of all our activities since both in the EU and Japan, SMEs are considered as the principal driver for economic growth. -

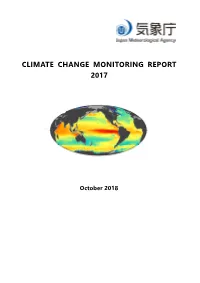

Climate Change Monitoring Report 2017

CLIMATE CHANGE MONITORING REPORT 2017 October 2018 Published by the Japan Meteorological Agency 1-3-4 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8122, Japan Telephone +81 3 3211 4966 Facsimile +81 3 3211 2032 E-mail [email protected] CLIMATE CHANGE MONITORING REPORT 2017 October 2018 JAPAN METEOROLOGICAL AGENCY Cover: pH distribution in 2016 in oceans globally (p11: Figure IV.2) Preface The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) has published annual assessments under the title of Climate Change Monitoring Report since 1996 to highlight the outcomes of its activities (including monitoring and analysis of atmospheric, oceanic and global environmental conditions) and provide up-to-date information on climate change in Japan and around the world. Extreme meteorological phenomena on a scale large enough to affect socio-economic activity have recently occurred worldwide. In 2017, the annual global average surface temperature was the third-highest since 1891 and extremely high temperatures were observed on a global scale. Heavy rains and tropical cyclones also caused widespread damage in southern China, the southeastern USA, Latin America and elsewhere. Japan’s northern Kyushu region sustained major damage as a result of heavy rainfall in July, and monthly mean temperatures in August and September at Okinawa/Amani were the highest on record. Significant meandering of the Kuroshio current was also observed for the first time in 12 years, and Japan’s Tokai region was severely damaged by high waves and storm surges associated with the intense Typhoon Lan, which made landfall on Shizuoka Prefecture in October. This report provides details of such events in Japan. -

Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Product Use in Japan

TC Online First, published on December 16, 2017 as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053947 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053947 on 16 December 2017. Downloaded from Research paper Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol Takahiro Tabuchi,1 Silvano Gallus,2 Tomohiro Shinozaki,3 Tomoki Nakaya,4 Naoki Kunugita,5 Brian Colwell6 ► Additional material is ABSTRACT Greece, Guatemala, Italy, Israel, Japan, Kazakh- published online only. To view Objectives A heat-not-burn (HNB) tobacco product, stan, Korea, Lithuania, Monaco, the Nether- please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ IQOS, was first launched in Japan and Italy as test lands, New Zealand, Palestine, Poland, Portugal, tobaccocontrol- 2017- 053947). markets and is currently in commerce in 30 countries. Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Using two data sources, we examined interest in HNB South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine and the 1 Cancer Control Center, Osaka tobacco (IQOS, Ploom and glo), its prevalence, predictors UK.2 IQOS is intended to compete with available International Cancer Institute, of its use and symptoms from exposure to secondhand Osaka, Japan electronic nicotine delivery systems, or e-ciga- 3 4 2Department of Epidemiology, HNB tobacco aerosol in Japan, where HNB tobacco has rettes, and other HNB tobacco products. Japan Laboratory of Lifestyle been sold since 2014. is the only country where a national roll-out of Epidemiology, Istituto di Methods Population interest in HNB tobacco was IQOS has occurred, and Japan's worldwide share of Ricerche Farmacologiche ’Mario explored using Google search query data. -

Assistive Device Revolution for the Independence of Older Adults in Japan

Assistive Device Revolution for the Independence of Older Adults in Japan Care Robots and Other Technology Innovations Yoko Crume, Ph.D. August 2018 ILC-Japan ILC (International Longevity Center) is a non-profit organization to study the trend of population aging with low-fertility from the international and interdisciplinary perspectives, to share the center's findings, to educate the public, and to make policy recommendations to the government. 17 centers have been established to date in the world: in the United States, Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Dominican Republic, India, South Africa, Argentina, Netherlands, Israel, Singapore, Czech Republic, Brazil, China, Germany, Canada and Australia. These centers constitute an alliance (called ILC Global Alliance) that promotes joint studies and symposia as well as country-specific activities within the context of this loose network. ILC-Japan has been engaged in numerous studies concerning the ethos of productive aging, and we have actively sought to share our findings and educate the public since 1990. We aspire to serve as an international resource center and will continue to proactively initiate projects that contribute to an ideal aging society, where all generations will support one another and live happily. ILC-Japan KDX Nishishinbashi Buldg., 6th Floor, 3-3-1, Nishishinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8446, JAPAN URL: http://www.ilcjapan.org E-mail: [email protected] This report was first published in June 2018. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Yoko Crume received her B.S. degree from International Christian University in Tokyo, Japan, and her M.S.W. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the United States. -

Foreigners in Japan: the 2020 Olympics As a Conduit for Better Policies

International ResearchScape Journal Volume 4 2016-2017 Article 7 5-2017 Foreigners in Japan: The 2020 Olympics as a Conduit for Better Policies Alexandra Cordes Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/irj Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Cordes, Alexandra (2017) "Foreigners in Japan: The 2020 Olympics as a Conduit for Better Policies," International ResearchScape Journal: Vol. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/irj/vol4/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International ResearchScape Journal by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Cordes: Foreigners in Japan: The 2020 Olympics as a Conduit for Better Po Cordes 1 Alexandra Cordes Professor Christopher J. Frey ASIA 4800 April 2017 Foreigners in Japan: The 2020 Olympics as a Conduit for Better Policies Contents 1. Introduction 2. Terminology 3. Background 4. Societal Attitudes 5. Historical Overview of Policy 6. Modern Policy and Future Outlook 7. Conclusion Works Cited 1. Introduction Japan has long been averse to foreigners entering the country and integrating into Japanese society. This is evident throughout its history, when the only times they interacted with foreigners was when they traded with them. Given that isolationist policy was forcibly terminated by Commodore Matthew Perry in the year 1852, it wasn’t of their own volition. (J.W. Hall, Japan, p.207) Despite the attitudes and adversity encountered in Japan, more and more foreigners have been residing within its borders, and their numbers continue to rise. -

Integrated Report 2018 Tokyo 102-8282, Japan Published in September 2018 Year Ended March 31, 2018 Profile & Growth Story

Yahoo Japan Corporation Kioi Tower 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku Integrated Report 2018 Tokyo 102-8282, Japan Published in September 2018 Year ended March 31, 2018 Profile & Growth Story Mission, Vision, and Values Firmly established as a “problem-solving engine,” Yahoo! JAPAN’s mission is to provide useful, solutions- oriented services by leveraging Internet technologies. In order to realize Yahoo! JAPAN’s vision of UPDATE JAPAN, we have formulated a set of five action guidelines entitled Yahoo! Values, which are thoroughly infused in our work culture and guide our day-to-day business activities. Mission Kentaro Kawabe Problem-solving Engine President and Representative Director, President Corporate Officer, Yahoo! JAPAN continues to pursue initiatives to solve problems in people’s daily lives and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) problems facing society by leveraging information technologies. As a “problem-solving engine,” Yahoo! JAPAN will contribute to people and society through its various businesses. In the 22 years since its founding, Yahoo Japan Corporation (“Yahoo! in which we promptly ascertain these changes and boldly take on JAPAN” or “the Company”) has expanded its business in accor- challenges in response, I believe we can achieve sustainable growth. dance with innovation in information technology. After riding the Going forward, we will continue to contribute to society by solv- waves of the desktop Internet generation, which focused on PCs, ing problems facing both people and society through information Vision and the mobile Internet generation, which focused on smartphones, technologies while we pursue efforts to further improve our corpo- Yahoo! JAPAN is now taking on challenges in the data generation, rate value. -

U.S. Extended Deterrence and Japan's Security “

Ambassador Satoh’s paper is a comprehensive and innovative analysis of the full range of issues and challenges for the US-Japan security “relationship in a dramatically changed regional security context. It describes the complex interplay of conventional and nuclear military capabilities, diplomatic efforts, and Japanese domestic opinion that determine and constrain the efforts of both nations to meet these challenges. In particular it affords a unique insight into Japanese political and societal perspectives on the problem and outlines practical steps – military, doctrinal, and diplomatic -- the US and Japan should each take to build cooperation on security and ensure a politically viable and militarily credible and effective extended deterrent in the coming years. Walter B. Slocombe“ U.S. Extended Deterrence Atlantic Council, former U.S. Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and Japan’s Security YUKIO SATOH China is rising, extending its reach, globally, with a new assertiveness. The U.S. is confused and is only partially defending the liberal and “intricate international system of the post WWII era. Thusly, Amb. Satoh’s clear and unambiguous declarations on Asian security are most needed and welcome, particularly, the centrality of Japan to peace and security in Asia. It is Japan and her security alliance with the U.S. which allows us to defeat the tyranny of time and distance which would define Asia. One of Japan’s wisest and most respected diplomats has served us well with this lucid and direct monograph. Richard L. Armitage “ Former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State The mission of the Center for Global Security Research is to catalyze broader national and international thinking about the requirements of effective deterrence, assurance, and strategic stability in a changed and changing security environment.