Washington State Airports Disparity Study 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington State and Nearby Airport Restaurant List 2018

Last revised: 1/29/2018 Washington State Airport Restaurants On Airport Specific Location Claim to Fame/ Airport Name Airport ID City Restaurant Name Website URL Phone Address (Yes/No) On/Off Airport Comments Midfield 2nd Location of 18218 59th Ave NE Arlington Airport AWO Arlington Ellie's at the Airport Yes Runway 16/34 360-435-4777 well-liked Local Diner Arlington, WA 98223 East Side 7 AM - 3 PM Applebee's All Are Within Blocks Hibachi Buffet Auburn Municipal Multiple Casual S50 Auburn No Via South Las Margaritas Hours Vary Airport and Fast Food Options Parking Apron Gate Iron Horse Casino Several Coffee & Fast Food Options Fish & Chips Inside Holiday Inn @ BLI Bellingham International http://www.northh2o. 4260 Mitchell Way 15% off to FBO BLI Bellingham Northwater No .25 miles from FBO 360-398-6191 Airport com Bellingham, WA 98226 Customers N on Mitchell Way 6:30 AM - 9 PM Mo-Su Greek .7 miles from FBO http://www.mykonos Bellingham International 1650 W Bakerview Rd 11 AM - 9 PM Mo-Th BLI Bellingham Mykonos Restaurant No S on Mitchell Way then restaurant 360-715-3071 Airport Bellingham, WA 98226 11 AM - 10 PM Fr E on W. Bakerview Rd bellingham.com 12 PM - 10 PM Sa-Su Inside 7277 Perimeter Rd S 7 AM - 6 PM Mo-Fr http://www.cavu Boeing Field (#1) BFI Seattle Cavu Café Yes King County 206-762-1243 Suite #200 11 AM - 3 PM Sa cafe.com Terminal Bldg Seattle, WA 98108 (Sa Apr-Sep Only) Crepes 1 Mile North of http://thehangar 6261 13th Ave S 7 AM - 3 PM Mon-Fri Boeing Field (#2) BFI Seattle Hangar Café No King County 206-762-0204 cafe.com/ Seattle, WA 98108 8 AM - 3 PM Sa Terminal Bldg 8 AM - 2 PM Su 1 Mile North of 1128 S. -

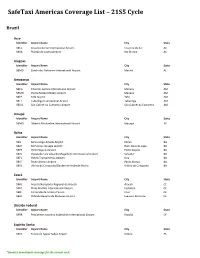

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Settlers 2019 Celebrating Our 98Th Year, July 26,27 and 28

Welcome to Settlers 2019 Celebrating our 98th Year, July 26,27 and 28 Grand Marshals Honored Settler Bill Sebright, was born and raised north of Clay- ton. He attended class for 6 years at Clayton School and 6 years in Deer Park. His family and he moved to the family farm, where he now lives, in 1948. He purchased the homestead from his folks in 1970. He graduated from Wash- ington State University in 1967 and taught in Red- wood City, California, for 5 years. For the next 30 years Bill taught at Clayton and Ar- travelled the Caribbean, pus for Deer Park School cadia Elementary. Three and voyaged through the District’s Home Link pro- other 6th grade teach- Panama Canal. gram. ers and he started the He is a charter mem- He represented The Outdoor Education Pro- ber of the Clayton Deer Golden Grads (Bill was gram at Camp Reed. He Park Historical Society part of The Class of 1963, Don Ball graduated from Deer Park High School in “coached” the Roadrun- (CDPHS) and has been the 50th class to gradu- 1948, the same class as his future wife. They met at ners and “Math is Cool” its President for 16 years. ate from Deer Park High the “Old Settlers” picnic, the oldest one in Washington teams for many years. He Bill is honored to have School) and CDPHS State. After graduating, Don married Lorraine in 1951 also set up a darkroom, written the application to as the commencement and joined the Air National Guard during the Korean taught photography and get the Clayton School speaker for the 100th War. -

2.0 Inventory of Existing Conditions

2014 Airport Master Plan Narrative Report 2.0 INVENTORY OF EXISTING CONDITIONS 2.1 INTRODUCTION AND PLANNING CONTEXT 2.1.1 GENERAL The purpose of the inventory is to summarize existing conditions of all the facilities at the Priest River Municipal Airport (1S6) as well as summarize other pertinent information relating to the community and the airport background, airport role, surrounding environment and various operational and other significant characteristics. The information in this chapter describes the current status of the Priest River Municipal Airport and provides the baseline for determining future facility needs. Information was obtained through various justifiable mediums including: consultant research, review of existing documents, interviews and conversations with airport stakeholders including the airport sponsor (Bonner County), City of Priest River, airport tenants, Idaho Transportation Department - Division of Aeronautics (ITD) and other knowledgeable sources. 2.1.2 FAA NATIONAL PLAN OF INTEGRATED AIRPORT SYSTEMS (NPIAS) AND ASSET STUDY The United States has developed a national airport system. Known as the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS), this system identifies public-use airports considered by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), state aviation agencies, and local planning organizations to be in the national interest and essential for the U.S air transportation system. Per the 2013- 2017 NPIAS Report to Congress, guiding principles of the NPIAS include: The NPIAS will provide a safe, efficient and integrated system of airports; The NPIAS will ensure an airport system that is in a state of good repair, remains safe and is extensive, providing as many people as possible with convenient access to air transportation The NPIAS will support a variety of critical national objectives such as defense, emergency readiness, law enforcement, and postal delivery. -

Northwest Mobilization Guide May 2020 CHAPTER 10 – OBJECTIVES, POLICY, and SCOPE of OPERATION

Northwest Mobilization Guide May 2020 CHAPTER 10 – OBJECTIVES, POLICY, AND SCOPE OF OPERATION MISSION STATEMENT 1 PRIORITIES 1 LOCAL AND GEOGRAPHIC AREA DRAWDOWN LEVELS AND NATIONAL READY RESERVE 1 SCOPE OF OPERATION 1 GENERAL 1 RESPONSIBILITIES OF NORTHWEST COORDINATION CENTER 1 RESPONSIBILITIES OF DISPATCH CENTERS 2 NWCC OFFICE STAFFING 2 NATIONAL RESPONSE FRAMEWORK (NRF) 2 HAZARDOUS MATERIALS 2 AIRCRAFT TRANSPORT OF HAZARDS MATERIAL – GENERAL 2 HAZMAT HANDBOOK/GUIDE 3 MOBILIZATION AND DEMOBILIZATION 3 WORK/REST, LENGTH OF ASSIGNMENT AND DAYS OFF 3 ASSIGNMENT EXTENSION 3 INCIDENT OPERATIONS DRIVING 3 INITIAL ATTACK DEFINITION 3 RESOURCE MOBILIZATION 3 NORTHWEST UNIT IDENTIFIERS 4 NATIONAL SHARED RESOURCES 6 NOTIFICATION OF COMMITMENT OF NATIONAL AND AREA RESOURCES 6 UNABLE TO FILL (UTF) PROCEDURE 6 STANDARD CUBES, WEIGHT, AND GEAR POLICY FOR ALL RESOURCES 6 TYPE I OR TYPE II TEAMS 6 COST CODING 6 USDI/BLM 6 USDI/BIA 6 USDI/NPS 7 USDI/FWS 7 USDA/USFS - DETERMINING INCIDENT JOB CODE 7 FIRE FOREST CONCEPT 7 NATIONAL FIRE PREPAREDNESS PLAN 9 NW PREPAREDNESS PLAN 9 SETTING PREPAREDNESS LEVELS 9 ORGANIZATION 10 NORTHWEST MULTI-AGENCY COORDINATING GROUP (NWMAC) ORGANIZATION 10 NORTHWEST INTERAGENCY COORDINATION CENTER ORGANIZATION 11 Northwest Mobilization Guide May 2020 RESOURCE ORDERING PROCEDURES FOR MILITARY ASSETS 12 ESTABLISHED RESOURCE ORDERING PROCESS 12 INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS 12 ORDERING CHANNELS 12 ORDERING PROCEDURES 12 NON-INCIDENT RELATED ORDERING 12 SUPPORT TO BORDER FIRES 12 PACIFIC CREST NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL (PCT) 12 NORTHWEST -

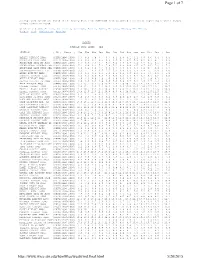

Page 1 of 7 5/20/2015

Page 1 of 7 Average wind speeds are based on the hourly data from 1996-2006 from automated stations at reporting airports (ASOS) unless otherwise noted. Click on a State: Arizona , California , Colorado , Hawaii , Idaho , Montana , Nevada , New Mexico , Oregon , Utah , Washington , Wyoming ALASKA AVERAGE WIND SPEED - MPH STATION | ID | Years | Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec | Ann AMBLER AIRPORT AWOS |PAFM|1996-2006| 6.7 8.5 7.9 7.7 6.7 5.3 4.8 5.1 6.1 6.8 6.6 6.4 | 6.5 ANAKTUVUK PASS AWOS |PAKP|1996-2006| 8.9 9.0 9.1 8.6 8.6 8.5 8.1 8.5 7.6 8.2 9.3 9.1 | 8.6 ANCHORAGE INTL AP ASOS |PANC|1996-2006| 6.7 6.0 7.5 7.7 8.7 8.2 7.8 6.8 7.1 6.6 6.1 6.1 | 7.1 ANCHORAGE-ELMENDORF AFB |PAED|1996-2006| 7.3 6.9 8.1 7.6 7.8 7.2 6.8 6.4 6.5 6.7 6.5 7.2 | 7.1 ANCHORAGE-LAKE HOOD SEA |PALH|1996-2006| 4.9 4.2 5.8 5.7 6.6 6.3 5.8 4.8 5.3 5.2 4.7 4.4 | 5.3 ANCHORAGE-MERRILL FLD |PAMR|1996-2006| 3.2 3.1 4.4 4.7 5.5 5.2 4.8 4.0 3.9 3.8 3.1 2.9 | 4.0 ANIAK AIRPORT AWOS |PANI|1996-2006| 4.9 6.6 6.5 6.4 5.6 4.5 4.2 4.0 4.6 5.5 5.5 4.1 | 5.1 ANNETTE AIRPORT ASOS |PANT|1996-2006| 9.2 8.2 8.9 7.8 7.4 7.0 6.2 6.4 7.2 8.3 8.6 9.8 | 8.0 ANVIK AIRPORT AWOS |PANV|1996-2006| 7.6 7.3 6.9 5.9 5.0 3.9 4.0 4.4 4.7 5.2 5.9 6.3 | 5.5 ARCTIC VILLAGE AP AWOS |PARC|1996-2006| 2.8 2.8 4.2 4.9 5.8 7.0 6.9 6.7 5.2 4.0 2.7 3.3 | 4.6 ATKA AIRPORT AWOS |PAAK|2000-2006| 15.1 15.1 13.1 15.0 13.4 12.4 11.9 10.7 13.5 14.5 14.7 14.4 | 13.7 BARROW AIRPORT ASOS |PABR|1996-2006| 12.2 13.1 12.4 12.1 12.4 11.5 12.6 12.5 12.6 14.0 13.7 13.1 | 12.7 BARTER ISLAND AIRPORT |PABA|1996-2006| -

President's Message…

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Stuart Island. Best Trip Ever! ................1 2014-11 Wings Legislative Report ..........1 Fall Foliage Flight ..................................3 IFR Training and Winter ........................5 Federal Grant Money Could Mean More Commercial Flights To and From Yakima Airport ....................................6 Pilots, Planes & Paella ............................7 Flying L Ranch .......................................8 December 2014-January 2015 President’s Stuart Island Could Be Your Best Trip Ever! Message… Photos and story by Travis Walters I have the distinct pleasure of flying a the pressure to get to Stuart Island before We didn’t expect much having never been WPA is an Symphony SA-160 out of Harvey airfield sunset, we rapidly loaded the plane with there and figured it would be pretty lean on all-volunteer (S43). I also belong to the Washington Pilots our cargo. Water, firewood, personal gear, amenities given it is sequestered on an island. organization Association and with that membership I can food and some fly-fishing equipment were It’s got be rough, right? Turns out its really working for use the cabin the association hosts on Stuart all unceremoniously tossed in the plane and quite nice! The ample number of vinyl framed General Aviation Island. I had never landed on the island and secured. After pre-flight and a quick run-up, windows are quite nice and look like they in the state of I certainly hadn’t been to the cabin so I’ve we put the throttle to the panel and set a direct had been recently installed. There are plenty W a s h i n g t o n . -

Fixed Wing Aircraft at Website

Aircraft Chapter 50 CHAPTER 50 AIRCRAFT Aircraft may be used for a wide range of activities, including point to point transport of personnel, equipment, and supplies. Tactical use may include applications such as retardant delivery, helicopter logistical and tactical support, air tactical and lead plane operations, suppression or pre-suppression reconnaissance, and aerial ignition. For more information review the National Aviation Safety and Management Plan at: https://www.fs.fed.us/fire/aviation/av_library/2017- 2018%20NASMP%20Approved%2024%20Jan%202017%20Directives%20Hyperlinks%20Updated%202 6%20Ja....508_Coverfixed.pdf AIRCRAFT MOBILIZATION Refer to NMG 50 Units requiring aviation services other than those assigned to them, through preapproved agreements, or within their dispatch boundaries, can order additional aircraft from adjacent units or through NWCC. At preparedness Levels 3-5, NWCC will coordinate aircraft assignment and utilization in the Northwest Area. The control of the aircraft assigned to a unit will remain with the local unit. In situations where the Northwest Multi-Agency Coordinating Group (NWMAC) has been activated, the NWMAC will coordinate with NWCC and local units on allocation and prioritization of aviation resources. AIRCRAFT SOURCES Sources for aircraft include agency-owned aircraft, Exclusive-Use and Call-When Needed (CWN) or On- Call Light Fixed Wing Aircraft and Helicopters. These aircraft may be ordered through established dispatch channels. Forest Service CWN helicopter contractors are assigned to a Host Forest Unit for administrative purposes and processing of Flight Invoices. Refer to CWN listings for helicopters and light fixed wing aircraft at website: http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r6/fire-aviation/?cid=fsbdev2_027111 DOI Bureaus may use the Office of Aviation Services (OAS) aircraft source list at website: https://www.doi.gov/aviation/aqd/aviation_resources Rental aircraft are signed up by the OAS under an Aircraft Rental Agreement (ARA). -

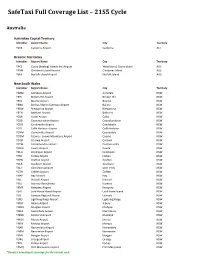

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Avigation Agreement

Avigation Easement What is an Avigation Easement? The intent of the Spokane County Airport Overlay Zone (Chapter 14.702) is to reduce the potential for airport hazards and incompatible development in proximity to the airports in Spokane County (Spokane International, Felts Field, Fairchild Air Force Base, and Deer Park Airport). Prior to issuance of a building permit within any of the airspace and/or Accident Potential Areas defined by the ordinance, property owners shall be required to award an avigation easement to the appropriate airport(s) and shall be required to record such easement with the Spokane County Auditor's Office. The airspace included in the overlay zone extends 30,000 lineal feet outward from the runway(s). Thus property located within 5.7 miles from the airport (measured in a straight line) is affected by the overlay zone. Development close to an airport may be required to restrict height and lighting in order to reduce the hazards to civil aviation. Avigation Easement Filing Instructions Complete Avigation Easement Worksheet Mail completed documents to: Deer Park Airport PO Box F Deer Park, WA 99006 OR Contact Airport Manager to arrange for meeting to sign documents Manager: (509) 276-3379 (509) 993-1620 AVIGATION EASEMENT WORKSHEET To properly evaluate any proposed structures and their relationship to Deer Park Municipal Airport, it is necessary to know the position of the proposed structure relative to the airport. Please complete the following steps. 1. Place an X where your proposed structure will be located on the map and note its height above ground. 2. Should the proposed structure be located off the map, please place an X with an arrow showing the approximate number of feet or miles the actual location is off the map (i.e.: X 1.2 miles ) on the closest point on the map. -

22478 Wings Oct-Nov 2013.Indd

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Rekindle That Avaiation Passion ........2 Port Townsend Museum ..................... 3 Plane Makes Emergency Landing ..... 3 2013 Scholarships ............................... 4 Vintage Aircraft Fly-In ....................... 5 RAF Awarded AOPA Foundation Grant ............................... 5 Safety & Education ............................. 6 Bremerton Blackberry Fly-In .............7 Unsung Generosity of the GA Community ....................................7 October-November 2013 President’s Message… Here on the west side, there has been a noticeable shift in the weather patterns, consistent with the fall season just ushered in. Along with kids back to school, there is an uptick in other indoor activities. We recently joined the Skagit Airport Support Association’s David Mischke to provide consultation at a meeting of Skagit County Planning and Development Services. Development threatens to encroach on Skagit Regional (Bayview). Your State Board voted to support Kristy Buck in her run for Port Commissioner in Port of Shelton with a contribution from our Political Action Committee (PAC) fund. We appreciate “It’s About Time” crew and pilot readying their aicraft to race at Reno. how Ms. Buck envisions a future of the fairgrounds off of the Port property and seeks a more desirable resolution to this issue by setting goals on a new “event center” for Mason Matt Burrows – Spokane Area’s County, one that will serve a multitude of purposes. We are supporting a legal action to avoid a sewage lagoon and it’s attraction of waterfowl and threat to safety Newest Reno Air Race Pilot in the proximity of Omak airport. Yours truly attended a PNBAA/NBAA Town Hall this week. Such collaboration The Spokane Area’s newest Reno Air Race pilot started College’s A&P classes and received my diploma and A&P will likely be helpful in this coming Legislative session. -

Wings 10-99 Final

WWASHINGTON PPILOTS AASSOCIATION 42nd Year No. 4 October-November 2003 $2.50 Inside WPAWings Another Super From h ! Page 2 Mountain Flying Clinic One Man Makes a Difference President’s Nesko on WASAR Tom Jensen, Airports Director WPA pilots also flew “High Bird” ! Page 3 during the weekend, to provide a high Message Wenatchee, September 12-14: altitude “Air Traffic Control”. WPA How To for Dummies H. Allen Smith ! Page 4 The WPA, WASAR, Wings of Although our flying does not Chapters - Deer Park, Harvey Wenatchee, WSDOT-AD and the include landings, John Black of the “$31.00 a month... do you know FAA again collaborated to conduct Spokane FSDO shared his wonderful how much gas that would buy?” was Field, Spokane th his response. I was at the WPA booth Int’l Lighting System to be the 9 Annual Mountain Flying Clin- backcountry flying presentation ic at Wenatchee. which really gets into the perfor- at the Arlington Air Show and was tested at Sanderson The Mountain Flying Clinic was mance side of that flying. John talking to a gentleman who was look- Ted Turner, Look Out! established as a free public service to Townsley, who recently served as the ing at our booth display. I had just ! Page 5 introduce interested pilots to safe and USFS airspace coordinator for the asked him if he would be interested Oregon-Wright Brthers enjoyable mountain flying. many fires in Montana, presented a in joining our 43 year old organiza- Connection Over a dozen volunteer mentor great tutorial on the five (!) different tion.