7 Warriors, Robbers and Priests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Wedding Ceremonies in Punjab

JPS: 11:2 Myrvold: Wedding Ceremonies in Punjab Wedding Ceremonies in Punjab Kristina Myrvold Lund University ______________________________________________________ While the religious specificities of different religious communities are underscored, the paper focuses on the shared cultural values and symbols that frame marriage ceremonies in the Punjab. The study concludes with how ritual theories help us analyse these ceremonies and assess the impact of modernity on their nature and function. ______________________________________________________ Traditional cultural practices in a society do not fade away or disappear in the face of modernization, but rather these practices transform and even become revitalized. This is illustrated in the case of religious and cultural rituals that Punjabis perform in relation to different stages of life. Rites of passage refer to a genre of rituals that people perform at major events in life--like birth, puberty, marriage and death. These types of rites characteristically mark a person’s transition from one stage of social life to another. The authoritative traditions of the world religions have sanctioned and institutionalized their own life-cycle rituals, which the followers share across different cultural and geographical contexts. Historically, religious authorities have often displayed a keen interest in defining these rituals to mark religious boundaries. Several studies that detail how Hindus, Jains, Muslim, Sikh, and Christians celebrate the birth of a child, perform weddings, and handle death in different parts of the world. Similarly, in the Punjab the core ceremonies related to these life events are distinct for every religious community, but yet they are performed within a shared Punjabi culture. This paper focuses on marriage (viah), the most celebrated life event in Punjabi society. -

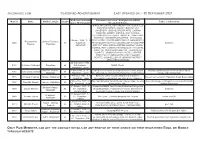

Jogsanjog.Com Classified Adveritsement Last Updated on :- 30 September 2021

JOGSANJOG.COM CLASSIFIED ADVERITSEMENT LAST UPDATED ON :- 30 SEPTEMBER 2021 DOB, time and birth Education Profession / Salary/Income PM/PA Matri id Name Nanihal , Origin Height Father 's information place 'M' if manglik /Occupation Details M.PHIL IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY (RCI LICENCED) MASTERS IN PSYCHOLOGY (BANASTHALI UNIVERSITY ) BACHELORS OF ARTS ( SOPHIA COLLEGE, AJMER) , CONSULTANT CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AT GOYAL HOSPITAL, MANIDHARI HOSPITAL, VASUNDHRA HOSPITAL, VRINDAVAN 5 October 1994 , 3 : 32 PSYCHIATRIC CENTRE DIRECTOR AT AMELIORATE ( Priyadarshini Udawat (Rathore) , 8240 63 , Rajasthan , PSYCHOLOGY CENTRE) COUNSELLOR AT JODHPUR Business Rajawat Rajasthan JODHPUR DISTRICT ARMY ORGANISATION MONTHLY 90,000, CONSULTANT CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AT GOYAL HOSPITAL, MANIDHARI HOSPITAL, VASUNDHRA HOSPITAL, VRINDAVAN PSYCHIATRIC CENTRE DIRECTOR AT AMELIORATE ( PSYCHOLOGY CENTRE) COUNSELLOR AT JODHPUR DISTRICT ARMY ORGANISATION 20 September 1990 , 8123 Dr Kusum Nathawat Rajasthan 66 Not Available , MBBS, Doctor Rajasthan , Jaipur Rathore- mertiya , 7 May 1996 , 2 : 45 , DVM (doctor of veterinary medicine) from CVAS, bikane, Assistant administrative officer at govt.medical 8173 Yashmita Shekhawat 64 Rajasthan Rajasthan , Jaipur Inte, ship student, Pursuing internship from CVAS, bikaner college and hospital,sikar 1 February 1991 , 5 : 0 Bachelor of Homeopathy Medicine and Surgery, 7515 Dr Neha Chauhan Tanwar , Rajasthan 64 Government servant in Rajasthan Khadi Board Jaipur , Rajasthan , Jaipur Successfully running Her own clinic at our residence -

Posting List of Dy.Sp., As on 01.04.2017 S

POSTING LIST OF DY.SP., AS ON 01.04.2017 S. No SH./ Name of officers Father Name Present Posting Place Date of Birth Home Distt. Date of SMT. Posting 1. SH. AAN RAJ RAJPUROHIT S/O SH.BAGH SINGH DY.SP. ACB 01/06/1971 BARMER 13/05/2015 2. SH. AAS MOHD. S/O SH.CHANDER KHAN ACP JHOTWARA JAIPUR POLICE (WEST) 25/01/1961 ALWAR 19/06/2016 3. SH. ABDUL AHAD KHAN S/O SH.A.R.KHAN CIRCLE JHUNJHUNU -RURAL JHUNJHUNU 10/07/1966 DAUSA 02/02/2017 4. SH. ABDUL AZIZ S/O SH.BASHIRUDDIN ASSTT.COMDT. R.A.C.-II KOTA 13/07/1957 KOTA 07/11/2015 5. SH. ABHAY KUMAR SHARMA S/O SH.SHYAM SUNDER SHARMA DY.SP. ACB 03/10/1973 JAIPUR 21/11/2016 6. SH. ABHAY SINGH BHATI S/O SH.NARPAT SINGH CIRCLE NIMBAHERA CHITTORGARH 17/03/1957 JAISALMER 07/11/2015 7. SMT. ADIT KANWAT D/O DR.MADAN LAL KANWAT DY.SP. GRP AJMER G.R.P. AJMER 26/03/1985 JAIPUR 02/02/2017 8. SH. AHAMAD SHRIF S/O SH.MUNAF ALI DY.SP ATRO(W/SC/ST) NAGAUR 21/04/1965 CHURU 18/02/2017 9. SH. AJAY SINGH S/O SH.MAHAVEER SINGH DY.SP.PTS BIKANER BIKANER 25/07/1966 SIKAR 02/02/2017 10 . SH. AJIT S/O SH.BABU LAL DY.SP. U/TRG. DISTT. NAGAUR 08/06/1986 JHUNJHUNU 29/12/2016 11. SH. AJIT SINGH S/O SH.SAJJAN SINGH CIRCLE BALESAR JODHPUR-RURAL 02/09/1960 PALI 02/02/2017 12 . -

Theorizing Radicalization in Pashtun Tribal Belt Along the Border of Afghanistan

• p- ISSN: 2521-2982 • e-ISSN: 2707-4587 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-II).07 • ISSN-L: 2521-2982 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-II).07 Ayaz Ali Shah* Nelofar Ehsan† Hina Malik‡ Jihad or Revenge: Theorizing Radicalization in Pashtun Tribal Belt along the Border of Afghanistan • Vol. IV, No. II (Spring 2019) Abstract What this research work does is to explore the relationship • Pages: 67 – 77 between radicalization and social traditions of Badal (revenge) in the tribal area of Pakistan. What is argued is that when someone is not guilty of any crime or not involved in any unlawful acts but killed even Headings by the most powerful like Americans, his revenge is considered to be a social • Introduction obligation by his closer kin of the family. In this process, they may sometimes • Individual-Level Inter-Disciplinary join organizations like Al-Qaeda or the Taliban in vengeance and often Model of Radicalization become an active member of a terrorist organization. What may be • An Integrative Model of Conversion established is that it is not a religion but the social customs of that particular • The Edge of Violence by Bartlett, area that help the locals undergo an unavoidable process of radicalization. Birdwell, and King For any tribesman, fixing revenge is so important as only this way the victim can live with honor among his community. • The Two-Pyramid Model • References Key Words: Jihad, Radicalization, Pashtun, Tribal, Afghanistan Introduction Since the Madrid and London bombings in 2004/05, as the threat and likelihood of homegrown radicalization has increased manifold, there has been a renewed discussion on why people embrace radicalization in the policy circles in every part of the world. -

1 CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of HARYANA Entry No Caste

CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF HARYANA Entry No Caste/ Community Resolution No. & Date Aheria 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Aheri 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Hari 1. Heri Naik Theri or Turi or Thori 2. Barra 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Beta 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 3. Hensi or Hesi 4. Bagria or Bagaria 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 5. Barwar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Barai 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 6. Tamboli Baragi 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 7. Bairagi 8. Battera 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Bharbhunja 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 9. Bharbhuja Bhat 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Bhatra 10. Darpi Ramiya 11. Bhuhalia Lohar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 12. Changar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 13. Chirimar 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 14. Chang 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Chimba or Chhimba, 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Chhipi, 12011/44/99-BCCdt. 21/09/2000 15. Chimpa, Darzi, Rohilla 16. Daiya 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 17. Dhobi 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 18. Dakaut 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. 10/09/1993 Dhimar, 12011/68/93-BCC(C) dt. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Riding Through Change History, Horses, and the Restructuring of Tradition in Rajasthan

Riding Through Change History, Horses, and the Restructuring of Tradition in Rajasthan By Elizabeth Thelen Senior Thesis Comparative History of Ideas University of Washington Seattle, Washington June 2006 Advisor: Dr. Kathleen Noble CONTENTS Page Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 1 Notes on Interpretation and Method History…………………………………………………………………………… 7 Horses in South Asia Rise of the Rajputs Delhi Sultanate (1192-1398 CE) Development of Rajput States The Mughal Empire (1526-1707 CE) Decline of the Mughal Empire British Paramountcy Independence (1947-1948 CE) Post-Independence to Modern Times Sources of Tradition……………………………………………………………… 33 Horses in Art Technical Documents Folk Sayings and Stories Col. James Tod Rana Pratap and Cetak Building a Tradition……………………………………………………………… 49 Economics Tourism and Tradition Publicizing Tradition Breeding a Tradition…………………………………………………………….. 58 The Marwari Horse “It's in my blood.” Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….. 67 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………… 70 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. District Map of Rajasthan…………………………………………………… 2 2. Province Map of India………………………………………………………. 2 3. Bone Structure in Marwari, Akhal-Teke and Arab Horses…………………. 9 4. Rajput horse paintings……………………………………………................. 36 5. Shalihotra manuscript pages……………………………………………….... 37 6. Representations of Cetak……………………………………………………. 48 7. Maharaj Narendra Singh of Mewar performing ashvapuja…………………. 54 8. Marwari Horses……………………………………………………………… 59 1 Introduction The academic discipline of history follows strict codes of acceptable evidence and interpretation in its search to understand and explain the past. Yet, what this discipline frequently neglects is an examination of how history informs tradition. Local knowledge of history, while it may contradict available historical evidence, is an important indicator of the social, economic, and political pressures a group is experiencing. History investigates processes over time, while tradition is decidedly anachronistic in its function and conceptualization. -

Identity and Difference in a Muslim Community in Central Gujarat, India Following the 2002 Communal Violence

Identity and difference in a Muslim community in central Gujarat, India following the 2002 communal violence Carolyn M. Heitmeyer London School of Economics and Political Science PhD 1 UMI Number: U615304 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615304 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

Remaking of Meos Identity: an Analysis

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(3): 3711 -3724 ISSN: 00333077 Remaking of MEOs Identity: An Analysis Dr. Jai Kishan Bhardwaj Assistant Professor, Institute of Law, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra ABSTRACT The paper revolves around the issue of bargaining power. It is highlighted with the example of Meos of Mewat that the process of making of more Muslim identity of the poor, backward strata of Muslims i.e. of Meos is nothing but gaining of bargaining power by elitist Muslims. The going on process is continue even more dangerous today which was initiated mostly in 1920’s. How Hindu cadres were engaged in reconversion of Meos with the help of princely Hindu states of Alwar and Bharatpur in the leadership of Swami Shardhanand and Meos were taught about their glorious Hindu past. With the passage of time, Hindu efforts in the region proved to be short-lived but Islamic one i.e. Tablighi Jamaat still continues in its practice and they have been successful in their mission to a great extent. The process of Islamisation has affected the Meos identity at different levels. The paper successfully highlights how the Meo identity has shaped as Muslim identity with the passage of time. It is also pointed out that Indian Muslim identity has reshaped with the passage of time due to some factors. The author asserts that the assertion of religious identity in the process of democratisation and modernisation should be seen as a method by which deprived communities in a backward society seek to obtain a greater share of power, government jobs and economic resources. -

Locals Rule: Historical Lessons for Creating Local Defense Forces For

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. LOCALS RULE Historical Lessons for Creating Local Defense Forces for Afghanistan and Beyond Austin Long, Stephanie Pezard, Bryce Loidolt, Todd C. -

List of Registered Lecturer for the Affiliated Colleges of MLSU, Udaipur

List of Registered Lecturer for the Affiliated Colleges of MLSU, Udaipur Sr. No. Candidate_i AppliedForPost Subject Name Father For B.Ed College For Degree College d 1 677 Lecturer ABST MUKESH GARG BANDHI LAL GARG NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 2 186 Lecturer ABST SURAJ KUMAR DAK PRAKASH CHANDRA DAK NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 3 742 Lecturer ABST Udit Varshney DrMadan Gopal Varshney NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 4 348 Lecturer ABST VIKAS GAHLOT GOVIND RAM GAHLOT NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 5 533 Lecturer ABST KIRAN KUMAR KHATIK BANSHI LAL KHATIK NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 6 829 Lecturer ABST Dr Nuzhat Sadriwala Hamid Ali Kutub NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 7 30 Lecturer ABST DEEPAK SONI YUDHISHTHAR SONI NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 8 31 Lecturer ABST Arti Gupta Sh Ravi Pal Gupta NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 9 254 Lecturer ABST BHAWANA KUMAWAT KISHAN LAL KUMAWAT NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 10 846 Lecturer ABST DR PRIYANKA JAIN PRABHU LAL JAIN NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 11 527 Lecturer ABST MUKESH OONTWAL SHANTI LAL OONTWAL NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 12 519 Lecturer ABST NAVEEN KUMAR YADAV PURUSHOTTAM YADAV NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 13 521 Lecturer ABST MANISH SAHU SATISH KUMAR SAHU NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 14 196 Lecturer ABST BHUVNESHWAR SHRIMALI VIJAY PRAKASH SHRIMALI NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 15 656 Lecturer ABST ASHOK KUMAR SHARMA GOPAL SHARMA NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 16 659 Lecturer ABST DR PRIYA JAIN BHAGWATI LAL JAIN NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 17 650 Lecturer ABST PAYAL KOTHARI KOMAL SINGH KOTHARI NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 18 201 Lecturer ABST MUKESH OONTWAL SHANTI LAL OONTWAL NOT ELIGIBLE ELIGIBLE 19 411 Lecturer ABST ANANDI LAL DHING SUNDER LAL DHING NOT ELIGIBLE NOT ELIGIBLE 1/40 List of Registered Lecturer for the Affiliated Colleges of MLSU, Udaipur Sr.