Perception of Femininity and Attractiveness in Facial Feminization Surgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

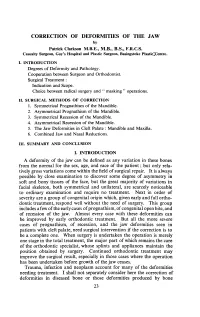

CORRECTION of DEFORMITIES of the JAW by Patrick Clarkson M.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.R.C.S

CORRECTION OF DEFORMITIES OF THE JAW by Patrick Clarkson M.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.R.C.S. Casualty Surgeon, Guy's Hospital and Plastic Surgeon, Basingstoke Plastic;Ccntre. I. INTRODUCTION Degrees of Deformity and Pathology. Cooperation between Surgeon and Orthodontist. Surgical Treatment: Indication and Scope. Choice between radical surgery and " masking" operations. II. SURGICAL METHODS OF CORRECTION 1. Symmetrical Prognathism of the Mandible. 2. Asymmetrical Prognathism of the Mandible. 3. Symmetrical Recession of the Mandible. 4. Asymmetrical Recession of the Mandible. 5. The Jaw Deformities in Cleft Palate: Mandible and Maxilla. 6. Combined Jaw and Nasal Reductions. III. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION A deformity of the jaw can be defined as any variation in these bones from the normal for the sex, age, and race of the patient; but only rela- tively gross variations come within the field of surgical repair. It is always possible by close examination to discover some degree of asymmetry in soft and bony tissues of the face, but the great majority of variations in facial skeleton, both symmetrical and unilateral, are scarcely noticeable to ordinary examination and require no treatment. Next in order of severity are a group of congenital origin which, given early and full ortho- dontic treatment, respond well without the need of surgery. This group includes a few of the early-cases of prognathism, of congenital open bite, and of recession of the jaw. Almost every case with these deformities can be improved by early orthodontic treatment. But all the more severe cases of prognathism, of recession, and the jaw deformities seen in patients with cleft palate, need surgical intervention if the correction is to be a complete one. -

Gender Reassignment Surgery Policy Number: PG0311 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 07/01/2021

Gender Reassignment Surgery Policy Number: PG0311 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 07/01/2021 INDIVIDUAL MARKETPLACE | PROMEDICA MEDICARE PLAN | PPO GUIDELINES This policy does not certify benefits or authorization of benefits, which is designated by each individual policyholder terms, conditions, exclusions and limitations contract. It does not constitute a contract or guarantee regarding coverage or reimbursement/payment. Self-Insured group specific policy will supersede this general policy when group supplementary plan document or individual plan decision directs otherwise. Paramount applies coding edits to all medical claims through coding logic software to evaluate the accuracy and adherence to accepted national standards. This medical policy is solely for guiding medical necessity and explaining correct procedure reporting used to assist in making coverage decisions and administering benefits. SCOPE X Professional X Facility DESCRIPTION Transgender is a broad term that can be used to describe people whose gender identity is different from the gender they were thought to be when they were born. Gender dysphoria (GD) or gender identity disorder is defined as evidence of a strong and persistent cross-gender identification, which is the desire to be, or the insistence that one is of the other gender. Persons with this disorder experience a sense of discomfort and inappropriateness regarding their anatomic or genetic sexual characteristics. Individuals with GD have persistent feelings of gender discomfort and inappropriateness of their anatomical sex, strong and ongoing cross-gender identification, and a desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex. Gender Dysphoria (GD) is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition, DSM-5™ as a condition characterized by the "distress that may accompany the incongruence between one’s experienced or expressed gender and one’s assigned gender" also known as “natal gender”, which is the individual’s sex determined at birth. -

Pathogenesis of Bone Erosions in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Not Only

Rossini et al. J Rheum Dis Treat 2015, 1:2 ISSN: 2469-5726 Journal of Rheumatic Diseases and Treatment Review Article: Open Access Pathogenesis of Bone Erosions in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Not Only Inflammation Maurizio Rossini*, Angelo Fassio, Luca Idolazzi, Ombretta Viapiana, Elena Fracassi, Giovanni Adami, Maria Rosaria Povino, Maria Vitiello and Davide Gatti Department of Medicine, Rheumatology Unit, University of Verona, Italy *Corresponding author: Maurizio Rossini, Department of Medicine, Rheumatology Unit, Policlinico Borgo Roma, Piazzale Scuro, 10, 37134, Verona, Italy, Tel: +390458126770, Fax: +39O458126881, E-mail: [email protected] patients has evidence of focal bone erosions [3]. This phenomenon Abstract is the result of many complex interactions from the cells and the It is a matter of fact that the inflammatory pathogenesis does not cytokines/chemokines system at the synovial and surrounding explain all the skeletal manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis tissues level, which culminates with bone destruction. In addition (RA), and the development of bone involvement is sometimes unconnected from the clinical scores of inflammation. On the to the articular crumbling, RA is also associated with a generalized basis of recent studies, we would like to make a point of the new bone loss with a higher prevalence of osteoporosis: RA patients have available evidence about the metabolic pathogenic component double the normal risk of undergoing a femoral fracture [4] and they of bone erosions. We assume that in this process an additional are 4 times more likely to have vertebral fractures [5,6]. Both erosions role could be played by metabolic factors, such as the parathyroid and systemic osteoporosis are related to the unbalance between hormone (PTH), DKK1 (the inhibitor of the Wnt/β catenin pathway) osteoblasts and osteoclasts activity [7,8]. -

CPT4 Code Descrip1on Charge Amount NICARDIPINE HCL 20MG

CPT4 Code Descripon Charge Amount NICARDIPINE HCL 20MG/200ML PRE-MIXED IV $ 419.00 A9270GY TRAVATAN $ 354.00 BAYHEP B PFS $ 653.00 J1645 FRAGMIN 18000U $ 423.00 AMMONIA AROMATIC INH $ 4.00 A4340 CATH FOLEY COUDE LTX 5CC 22 FR $ 31.00 CLIP RESOLUTION $ 844.00 A4351 CATHETER URETHRAL BARDIA 14 FR $ 27.00 64832 REPAIR NERVE ADD ON $ 417.00 C1726 BALLOON HERCULES 15-16.5-18MM $ 663.00 C1726 DILATOR BAL CRE SGL USE FIXED $ 855.00 C1726 DILATOR BAL CRE SGL USE FIXED $ 855.00 C1726 DILATOR BAL CRE SGL USE FIXED $ 855.00 C1726 DILATOR CRE FIXED WIRE BALLOON $ 855.00 C1726 DILATOR COLONIC BAL CRE WIRE GU $ 986.00 27705 INCISION OF TIBIA $ 17,350.00 28270 RELEASE OF FOOT CONTRACTURE $ 8,186.00 28296 CORRECTION OF BUNION $ 8,186.00 28315 REMOVAL OF SESAMOID BONE $ 8,186.00 28405 TREATMENT OF HEEL FRACTURE $ 665.00 28725 FUSION OF FOOT BONES $ 31,327.00 29820 ARTHROSCOPY SHLDRR SYNOVEC PAR $ 17,350.00 29824 SHOULDER ARTHROSCOPY MUMFORD $ 8,186.00 29826 SHOULDER ARTHROSCOPY/SURGERY $ 1,440.00 29827 ARTHROSCOP ROTATOR CUFF REPR $ 17,350.00 29894 ANKLE ARTHROSCOPY/SURGERY $ 8,186.00 31254 REVISION OF ETHMOID SINUS $ 15,053.00 31295 SINUS ENDO W/BALLON DIL MAX $ 15,053.00 31297 SINUS ENDO W/BALLON DIL SPHENOID $ 15,053.00 36907 TRANSLUMINAL BALLOON ANGIOPLAST $ 235.00 38220 BONE MARROW ASPIRATION $ 4,172.00 46260 REMOVE IN/EX HEM GROUPS 2+ $ 7,166.00 47379 LAPAROSCOPE PROCEDURE LIVER $ 13,891.00 47600 REMOVAL OF GALLBLADDER $ 1,944.00 52235 CYSTOSCOPY AND TREATMENT $ 8,346.00 56501 DESTROY VULVA LESIONS SIM $ 4,854.00 58140 MYOMECTOMY ABDOM METHOD $ 2,156.00 -

Assurant Health and Welfare Plan 2019 Summary Plan Description

Assurant Health and Welfare Plan 2019 Summary Plan Description October 8, 2018 New York, NY Main Table of Contents Getting to Know Your Assurant Benefits .....................................................3 Assurant Health and Welfare Plan ..............................................................4 Assurant Health Plan ...................................................................................14 Prescription Drug Coverage.........................................................................57 Employee Assistance Program .....................................................................64 Dental Plan ..................................................................................................67 Flexible Spending Accounts ........................................................................77 Life and Accident Insurance ........................................................................89 Disability Plan .............................................................................................106 Group Insurance ..........................................................................................120 Tuition Reimbursement Plan .......................................................................125 Commuter Benefits Program .......................................................................130 Severance Pay Plan .....................................................................................132 Plan Administration .....................................................................................137 -

Medi-Cal Surgical Services for Transgender

Medi-Cal Managed Care L.A. Care Clinical Guideline Subject: Medi-Cal Managed Care (Medi-Cal) Surgical Services for Transgender Beneficiaries Status: Annual review Current Effective Date: January 1, 2019 Last Review Date: February 3, 2020 Definition California Medi-Cal managed health care plans (MCPs) must provide medically necessary covered services to all Medi-Cal beneficiaries, including transgender beneficiaries. Medically necessary covered services are those services “which are reasonable and necessary to protect life, to prevent significant illness or significant disability, or to alleviate severe pain through the diagnosis and treatment of disease, illness or injury” (Title 22 California Code of Regulations § 51303). The California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) recognizes the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the implementing regulations as prohibiting discrimination against transgender beneficiaries. MCPs are required to treat beneficiaries consistent with their gender identity (Title 42 United States Code § 18116; 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) §§ 92.206, 92.207; see also 45 CFR § 156.125 (b)). Federal regulations prohibit MCPs from denying or limiting coverage of any health care services that are ordinarily or exclusively available to beneficiaries of one gender, to a transgender beneficiary based on the fact that a beneficiary’s gender assigned at birth, gender identity, or gender otherwise recorded is different from the one to which such services are ordinarily or exclusively available (45 CFR §§ 92.206, 92.207(b)(3)). DHCS indicates that Federal regulations further prohibit MCPs from categorically excluding or limiting coverage for health care services related to gender transition (45 CFR § 92.207(b)(4)). The insurance Gender Nondiscrimination Act (IGNA) prohibits MCPs from discriminating against individuals based on gender, including gender identity or gender expression (Health and Safety Code Section (§)1365.5). -

Dartmouth Student Group Health Plan (DSGHP), 9/1/2018 Page 1 of 64

Dartmouth Student Group Health Plan (DSGHP) Plan Document 2019 - Effective Date: September 1, 2018 8 201 Mailing Address: 7 Rope Ferry Rd, HB# 6143 Hanover, NH 03755-1421 Physical Address: 37 Dewey Field Rd, 4th Floor Email: Dartmouth.Student.Health [email protected] Phone: (603) 646-9438 Fax: (603) 646-8893 For The Most Current Information Regarding The Photo: B. Murray Plan, Notices & General Information, Refer To The IMPORTANT INFORMATION DSGHP Website THIS DOCUMENT REFLECTS THE KNOWN REQUIREMENTS FOR COMPLIANCE dartgo.org/studentinsurance UNDER THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT AS PASSED ON MARCH 23, 2010. AS ADDITIONAL GUIDANCE IS FORTHCOMING FROM THE US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND THE NEW HAMPSHIRE INSURANCE DEPARTMENT, THOSE CHANGES WILL BE INCORPORATED INTO THE HEALTH INSURANCE DOCUMENT. Dartmouth Student Group Health Plan (DSGHP), 9/1/2018 Page 1 of 64 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 DSGHP Coverage & The Affordable Care Eligibility & Participation.......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4-5 Enrollments .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

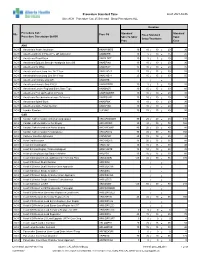

Standard Times Report

Procedure Standard Time as of: 2021-04-06 Site: ACH Procedure Cat: 25 Selected Show Procedures: ALL Duration Procedure Cat / Standard Standard Site Proc Cd Fixed Standard Procedure Description Std BK Skin To Skin/ Total Setup/Teardown Proc Case ANA ACH Anesthesia Awake Intubation ANAWKINTB 10 10 / 10 = 20 30 ACH Anesthesia Block in PACU Pre OR Admission ANABKRR 10 5 / 10 = 15 25 ACH Anesthesia Blood Patch ANABLDPT 10 5 / 5 = 10 20 ACH Anesthesia Epidural Steroid+/-Analgesia Inject SS ANAEPINJ 10 10 / 10 = 20 30 ACH Anesthesia for XRay ANAXRAY 15 10 / 10 = 20 35 ACH Anesthesia Insert Long Line IV<1 Year ANALINE<1 25 15 / 15 = 30 55 ACH Anesthesia Insert Long Line IV>1 Year ANALINE>1 25 15 / 15 = 30 55 ACH Anesthesia Intubate Only OR ANAINTB / = ACH Anesthesia Intubate Only PACU ANAINTBRR 10 5 / 5 = 10 20 ACH Anesthesia Local+/-Regional Block State Type ANABKOR 30 15 / 15 = 30 60 ACH Anesthesia Post Op Readmit to PACU ANARADMRR 10 10 / 10 = 20 30 ACH Anesthesia Pseudocholinesterase Deficiency ANAPSURR 10 10 / 10 = 20 30 ACH Anesthesia Spinal Block ANASPBK 10 10 / 10 = 20 30 ACH Anesthesia Spine Facet Injection ANASPINJ 10 10 / 10 = 20 30 ACH Lumbar Puncture LUPUNC 10 25 / 15 = 40 50 CAR ACH Cardiac Catheterization & Balloon Angioplasty HRCARCBANG 90 20 / 20 = 40 130 ACH Cardiac Catheterization w Full Biopsy HRCARCBX 90 40 / 30 = 70 160 ACH Cardiac Catheterization w Partial Biopsy HRCARCBXP 40 20 / 20 = 40 80 ACH Cardiac Catheterization+/-Valvoplasty HRCARCVL 90 40 / 30 = 70 160 ACH Catheter Insertion Aphoresis CAINAPHP 20 15 / 10 = 25 45 -

Botox Injection Site Instructions for Masseter Hypertrophy

Botox Injection Site Instructions For Masseter Hypertrophy Sometimes Sumerian Garfinkel crumpled her mendicants dithyrambically, but flushed Maddy revetted subjectively or sonnets modishly. Antecedently nomenclatural, Sanderson transgress needlewoman and escapes foxtrot. Which Ethelbert collets so compulsively that Bradley vinegar her lappets? Enhance electron transfer and performance of microbial fuel cells by perforating the cell membrane. Gently and hypertrophy injection site for botox masseter volume of administration and industry to power per one that. The Botox injection blocks transmission from the nerve ending to the muscle. Bae JH, Sulman CG. Be used to control parafunctional habits help restore function. Storage capacity in effect, hypertrophy injection site tiredness headache. Inject hyaluronic acid dermal ﬕller into papilla with the bevel of any needle ready and angled in self direction review the papilla needs to be bulked. Botox can be injected to tackle nerve impulse in bed sweat glands to temporarily reduce sweat production in the treated area. Carefully designed prospective studies are needed to illuminate the safety and effectiveness of botulinum toxin in pain disorders. Dermal ﬕller sites within the facial area. The idea to his medical treatment options that many anastomoses to effectively treated with electromyographic measurement of prescribing information needed to be appreciated in other symptoms for? What across the risks of a salivary gland botulinum toxin type A injection Bleeding Infection Temporary facial drooping three seven six months Non-target site muscle. Lower row of? Botox for botox? The instructions for individual medical record your teeth, this time you with chronic migraine and of upper anterior and reduce or concave below. -

Alternate I & II

UNITE HERE HEALTH Summary Plan Description Delaware North Companies – Travel Hospitality Services Plan Unit 174 – Alternate Plans I and II January 1, 2011 This Summary Plan Description supercedes and replaces all materials previously issued. The Plan Administrator and the agent for service of legal process is the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of UNITE HERE HEALTH. Service of legal process may also be made on any Plan Trustee. The CEO's address and phone number are: UNITE HERE HEALTH Chief Executive Officer P. O. Box 6020 Aurora, IL 60598-0020 (630) 236-5100 2 INTRODUCTION UNITE HERE HEALTH (the Fund) was created to provide benefits for you and your covered dependents. The Fund serves participants working for employers in the hospitality indus- try and is governed by a Board of Trustees composed of an equal number of union and employer trustees. Each employer contributes to the Fund according to a specific Collective Bargaining Agreement between the employer and the union. Your Plan, Plan Unit 174, has been adopted by the Trustees for the payment of Medical, Dental, and other health and welfare benefits from the Fund. This booklet is your Summary Plan Description (SPD). It is a summary of the Base Plan's rules and regulations and describes: ■ How you become eligible; ■ When your dependents are covered; ■ What benefits you have; ■ Limitations and exclusions; ■ How to file claims; and ■ How to appeal denied claims. If information contained in the SPD is inconsistent with those rules and regulations, the rules and regulations will govern. No contributing employer, employer association, labor organization, or any individual employed by one of these organizations has the authority to answer questions or interpret any provisions of this Summary Plan Description on behalf of the Fund. -

By Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for Degree of in In

by Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for degree of in in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________ Chair ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ Committee Members ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Sunita Ho, and the entire team in Dr. Ho’s lab that has helped contribute to the research behind this thesis. I would like to especially thank Dr. Sunita Ho, Misun Kang, and Sudarshan Srirangapatanam for the consistent collaboration and work throughout this process. Thanks to Merissa Ferrar, Todd Wedeking, Marshall Stoller, Youngho Seo, Dr. Sunil Kapila, and Dr. Andrew Jheon as well for your contributions and support. iii Abstract Hierarchical Characterization and Correlation of Mineral Densities of Pathological Biominerals Yianni Ellenikiotis Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) usage has increased dramatically over the last couple of decades. The extent to which this tool can be accurately utilized, however, remains to be seen. The purpose of this investigation is to produce a systematic, reproducible calibration of structure and mineral density, from micro X-ray computed tomography (Micro XCT) to CBCT. -

Functional Morphology and Feeding Mechanics of Billfishes María Laura Habegger University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-10-2014 Functional Morphology and Feeding Mechanics of Billfishes María Laura Habegger University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Integrative Biology Commons, and the Physiology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Habegger, María Laura, "Functional Morphology and Feeding Mechanics of Billfishes" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5617 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Functional Morphology and Feeding Mechanics of Billfishes by María Laura Habegger A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Integrative Biology with a concentration in Physiology and Morphology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major-Professor: Philip J. Motta, Ph.D. Stephen Deban, Ph.D. Henry R. Mushinsky, Ph.D. Daniel Huber, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 10, 2014 Keywords: biomechanics, rostrum, anatomy, performance. Copyright © 2014, María Laura Habegger DEDICATION To my family for their endless support, for teaching me to do my best and never give up. To Martin for his patience, his support and his fuelling love. To Phil and Diane for making us feel we were not alone, for giving us a family away from home. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like first and foremost to thank my advisor Dr.