NDSU Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Mr. Willis Conover

Library of Congress Interview with Mr. Willis Conover The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series WILLIS CONOVER Interviewed by: Cliff Groce Initial interview date: August 8, 1989 Copyright 2009 ADST Q: How did Music USA get started? CONOVER: In 1954, when I was working in a Washington, DC area radio station, I just happened to overhear one announcer saying to another, “I hear the Voice of America is looking for someone to do a jazz program.” Q: And you were doing a jazz program. CONOVER: In commercial radio I was doing all the stuff that had to be done - newscasts, commercials, and commercial music, plus - against the will of the sales department and the management - a jazz program, too. I thought, you mean they're looking for someone to do the kind of thing that I want to be doing - not because it's jazz but because there's more interesting music to be found in that category than in many other categories, certainly more interesting than in any so-called “top forty” group of popular music. And so I got in touch with the deputy program manager of the Voice of America. That is, I called the Voice of America, and he was the one who got the call. His name was John Interview with Mr. Willis Conover http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib001532 Library of Congress Wiggin, and he said, “Please come by.” Well, inside of the first 30 seconds of talk in his office, each of us was aware that the other person knew something about jazz. -

TAILGATE RAMBLINGS TAILGATE RAMBLINGS April, 1979 Volume No

TAILGATE RAMBLINGS TAILGATE RAMBLINGS April, 1979 Volume No. 4 The President’s Corner (Continued) EDITOR: Ken Kramer NATIONAL CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Another piece of encouraging news is George Kay Floyd Levin that we have some hope of a site for CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: our regular Sunday night sessions. Mary Doyle Fred Starr These would be for local bands Joe Godfrey Dick Baker exclusively and w'e have been searching Ted Chandler Harold Gray for a good spot for months. It is too early to predict what our present, very POTOMAC RIVER JAZZ CLUB preliminary negotiations will bring President Ray West 370-5605 about, but about all that can be said Vice Pres. Mary Doyle 280-2373 now is that the spot will not be the PRJC Hot Line 703-573-TRAD same as before. So you see, traditional jazz is very TAILGATE RAMBLINGS IS PUBLISHED much alive and well in PRJC land! MONTHLY BY THE POTOMAC RIVER JAZZ CLUB. I would like to mention the quickly- THE CLUB IS FOR THE PURPOSE OF assembled function on February 25 in PRESERVING, ENCOURAGING AND ADVANCING honor of Royal Stokes for his great TRADITIONAL JAZZ. support of PRJC and jazz in general. A plaque was presented by yours truly in The President's Corner the name of the PRJC. A good crowd was there, in spite of the shortness of Here we are once more and with all advance notice and I apologize to all sorts of good tidings. The year who did not get the word in time. And started off in a most encouraging to Royal, our very sincere gratitude way for the club. -

Duke Ellington, Performing at Fargo's Crystal Ballroom. Right, Richard

Duke Ellington, performing at Fargo’s Crystal Ballroom. Right, Richard Burris and Jack Towers Photos taken by Jack Towers during Fargo recording, except where indicated. THE TWO MEN WHO LUGGED SOUND EQUIPMENT OUT THE STAGEDOOR OF THE CRYSTAL BALLROOM IN DOWNTOWN FARGO IN THE EARLY HOURS OF A NOVEMBER 1940 MORNING HAD NO IDEA THEY CARRIED WITH THEM A PIECE OF JAZZ HISTORY. SOME 40 YEARS LATER, AS A RESULT OF ONE OF THOSE PRECIOUS ACCIDENTS OF HISTORY, THE SIX ACETATE DISCS THEY RECORDED WOULD WIN A GRAMMY AWARD. THURSDAY NOVEMBER 7,1940. that carved v-tracks in 16-inch acetate discs. They Franklin Delano Roosevelt has just been elected to placed the recorder next to Ellington’s piano with a third term as president of the United States. The two additional microphones, one up high and one attack on Pearl Harbor is 13 months away, but North down low at the front of the stage. After the orchestra Dakotans are anxious about the war in Europe. played two or three warm-up pieces, Ellington came Students at North Dakota Agricultural College, out to his piano. The band played “Sepia Panorama,” still licking their wounds from a Homecoming gridiron its broadcast theme — local radio station KVOX loss to North Dakota University the previous weekend, broadcast part of the show live — and, “Away the warm up for a fun-filled evening of dancing at the program went.” Crystal Ballroom. An NDAC Extension Service By all accounts the night was magical. Between 600 employee prepares for the arrival of his friend from and 800 people paid the $1.30 advance ticket price South Dakota State College in Brookings, S.D. -

Ellington '99 Program

Elliryton'99 The 17th Annual International Duke Ellitgton Conference 'Eduard, You Are Blessed!' April 28 r Muy 2, 7999 Celebrating the 100th Anniversary Of His Birth 7he Washington Marriott f{otel Washington, ,DC trllington'99 lTth Annuel lntcmational Duke Ellington Gonfcruncc April 28 - May 2, 1999 'Edward, You Are 8/essed.' April 28, 1999 Dear Ellington Lovers: It is indeed a great pleasure, as president of the oldest chapterof the Duke Ellington Society] tq welcomg yori to-our capital city. This is the third time we have enterraitirJ ttrr-Cilfei."ce. We staited it alt in 1983 and tioGO the seventh in 1989; and here we are again,witb the seventeenth,.it S. C.nirn"ial veii-oiEttitt*6n's birth. It is fitting that this commemoration be il;d;iii;,if ttir birttt__W. have attempted to mdke this an event you will long remember. We have had a pfeater percentage of our members attend these Conferences th; ftu"" tftose 6f any other chalter. 9ne of our members has ;td;a;a afoftfte*, *a tno otheis have misded gqly one. We do hope that some our famous v"" *i]l- iake--"4":""tug.--- of t;* ttuy and visit of 'uttiuriio"t b,tr museums, moiruments, memorials, archives and theaters. V;; rnisht .".r. o"i new MCI Center and watch our professional Uu"rl.iUu-ffi"urn,Tt "iiirwirurOs- At any rate, wo wish ygu a memorable stay, and ur o,rt celebrated composer" would iay at the drop of a baton, We love you madly . Shell, D.D.S. bl I I N I PO Box 42504. -

THE NEWSLETTER of the DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY (UK) VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1 L SPRING 2011

BLUE LIGHT THE NEWSLETTER OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY (UK) VOLUME 18 NUMBER 1 l SPRING 2011 THE NEW MOSAIC 11 CD SET HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK In alphabetical order Alice Babs Art Baron Buster Cooper Herb Jeffries John Lamb Vincent Prudente Monsignor John Sanders Joe Temperley Editorial Clark Terry Welcome to the first Blue Light of 2011 (really itÊs the second, since HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO 17/4 reached you so late). Complications with the preparation for LONGER WITH US Bill Berry (13 October 2002) printing delayed 17/4 into the New Year, and by then further Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) commitments and frustrations led to further delays. I apologize to you Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) all, but above all to the musicians and promoters whose announcements Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) appear in the Events Calendar. For more of the grisly details, turn to the Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) inside back cover. Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) * Letters or editorial material should IÊm also sorry if what I wrote about the three vacancies made some of be addressed to: you fearful for DESUKÊs future. All three vacancies will be filled at the Roger Boyes, 9 Chester Place, Great 7 May AGM, and the SocietyÊs future seems secure. See p6 for details Barton, Bury St Edmunds, IP31 2TL about the AGM and p1 for our progress on filling the vacancies. I hope Phone: 01284-788200 to see many of you in London on the day. At the meeting Derek Else will Email: [email protected] retire as Treasurer and Membership Secretary (and much more – at times DESUK Website: http://www.dukes-place.co.uk he came near to shouldering the burden single-handedly). -

Guide to the Duncan P. Schiedt Photograph Collection

Guide to the Duncan P. Schiedt Photograph Collection NMAH.AC.1323 Vanessa Broussard Simmons, Franklin A. Robinson Jr., and Craig A. Orr. Processing and encoding funded by a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources. 2016 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Background Information and Research Materials, 1915-2012, undated..................................................................................................................... 4 Series 2: Photographic Materials, 1900-2012, -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. NAT HENTOFF NEA Jazz Master (2004) Interviewee: Nat Hentoff (June 10, 1925 – January 7, 2017) Interviewer: Loren Schoenberg with audio engineer Ken Kimery Date: February 17-18, 2007 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 80 pp. Schoenberg: It’s February 17th, 2007. We’re at 35 West 12th Street in New York City. My name is Loren Schoenberg. Our guest is Nat Hentoff. We’re interviewing him for the Smithsonian Oral History project. I start off by saying, Nat, this is something I’ve been looking forward to do for a long time. It’s an honor to be talking to you this afternoon. Hentoff: Thank you sir. It’s an honor to talk to somebody who’s an actual musician, not a jazz master without a horn. Schoenberg: We’re talking with Nat Hentoff. There are so many places to go in this interview. Before I ask a question – I’m going to hopefully disappear pretty soon as a voice on this tape, because you don’t need to hear me asking questions – I want to set a groundwork and context for the interview, the things that I would like to focus on, at least for a starter. We’re talking with someone here who was on a personal level friendship with, just to name a few people, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Frankie Newton, Jo Jones, and Sidney Bechet. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series WILLIS CONOVER Interviewed by: Cliff Groce Initial interview date: August 8, 1989 Copyright 2 9 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Origins of — usic U.S.A.# And How Conover Got Started IN )OA Evolution Of The Program Over The Years Early Signs Indicating The Program ,as Successful Over The Years Conover )isits Several Countries To eet His Fans. First And ost Tumultous Stop- ,arsaw. 1909 Some of Conover1s E2periences On His )arious Overseas )isits Conover Discusses His Philosophy of usic. Its Programming ethodology. And His Distaste For ,hat He Considers Distasteful Productions That Pass For usic Today Generally. Conover Has Had Strong Support For His Program From 3oth Directors of )OA And USIA. Cites Particularly 4ohn Chancellor Some of Conover1s Special Programs. Particularly ,ith Du5e Ellington6 Ellington At The ,hite House And Numerous Other Times During Ni2on. 4ohnson. Carter Administrations The Story of How The Irving 3erlin Show Celebrating Composer1s 80th 3irthday. ,as Put Together And. The Update of The Program Celebrating His 1 100th 3irthday Conover1s Determination To Remain Non-Political On The Air Conover1s Assistance To Foreign usicians of erit Conover Compliments His Engineers ,ith An Occasional E2ception A Tale Of 4ealousy-Induced Low 3lows 3ac5 To Discussion Of Foreign usicians- Conover1s Help To Polish 4azz Pianist Adam a5owicz. The Outcome Of That Assistance A Chinese ,oman ,ho ,as Still in China During The Cultural Revolution. 3ecomes A Conover Fan As A Listener To )OA. Later 3ecomes rs. Conover INTERVIEW $: How did Music USA get started( CONO)ER- In 1904. -

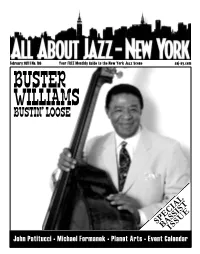

Bustin' Loose

February 2011 | No. 106 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene aaj-ny.com BUSTER WILLIAMS BUSTIN’ LOOSE SPECIAL BASSISTISSUE John Patitucci • Michael Formanek • Planet Arts • Event Calendar Perhaps more than any other instrument, the look and sound of the acoustic bass defines what most people think of when they think jazz. It conjures up images of dimly-lit clubs and some bassist slumped over their instrument, eyes closed, coordinating the maelstrom around them. But for their almost supreme importance, people still talk during the bass solo and think it odd when a bassist New York@Night leads a group. We hope our special Bass Issue will change that. 4 While we’ve had previous issues devoted to a single instrument, not once have we gone this overboard. On The Cover we have the seminal Buster Williams, Interview: John Patitucci whose resumé reads like jazz history and brings a quartet to Iridium. Interview 6 by Terrell Holmes John Patitucci, besides his work as a leader, has been an integral part of many important groups, perhaps none more so than the quartet of Wayne Shorter, with Artist Feature: Michael Formanek whom Patitucci appears at Town Hall this month. Michael Formanek (Artist 7 by Kurt Gottschalk Feature) is known more for being an in-demand sideman since the early ‘80s but has had his forays into leadership, including last year’s acclaimed The Rub and On The Cover: Buster Williams Spare Change (ECM), the group from which will appear at Connection Works’ 9 by Ken Dryden monthly showcase at Littlefield. -

Kuebler the Duke at Fargo

Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 137-162 (Winter 2012) The Duke At Fargo Annie Kuebler Liner notes from The Duke at Fargo 1940: Special 60th Anniversary Edition (Storyville STCD 8317/17)* Time present and time past Are both perhaps in time future, And time future contained in time past.1 -T.S. Eliot Ten years past, the curtains parted at the opulent Cotton Club, in New York City's Harlem district, to reveal Duke Ellington & His Jungle Band, resplendent in their showman's suits. The band, positioned behind the sepia- colored dancers and an emcee in blackface and minstrel attire, performed a stageshow for celebrities, gangsters and other mature, white wealthy new Yorkers. The gentlemen in tuxedos and the ladies, dressed to the nines, paid their $1.50 admission and crowded around clothed tables, stashing their prohibited liquor underneath. The same piano player, the same drummer, four, the only four out of five, saxophonists, two, the only two out of three, trombonists, and not one of the same trumpet players at Fargo, North Dakota opened the Cotton Club show with their theme song East St. Louis Toodle- Oo. Forget time future from 1940 on, pay your $1.50 admission and walk into time present, sixty years ago, the Crystal Ballroom in Fargo, North Dakota on November 7, 1940. You are early. Barney Bigard, Ivie Anderson and several other band members sit on the stage around a card table, pursuing their favorite pastime--playing cards. Only a new face, Ray Nance, is eagerly dressed in the band uniform of matching striped ties, light sports coats and dark trousers. -

Tailgate Rambliags

Tailgate Rambliags “You knew when you married me that I couldn’t shimmy like my sister Kate.” DRAWING BY GEO. PRICE; (g) THE NEW YORKER MAGAZINE, INC. APRIL 1980 TAILGATE RAMBLINGS VOLUME 10, NUMBER 4 A p ril 1980 JAZZ BAND BALL SYNOPSES APRIL 1980 Editor: Ken Kramer WPFW, 89.3 FM Contributing Editors: Sundays, 6:00-7:30 PM Mary Doyle Harold Gray Joe Godfrey Dick Baker April 6. Host Jim Lyons. "Between George Kay Floyd Levin Reisenwebers and the Lincoln Gardens" — how Vivienne Brownfield we jazzed our way through World War I, women's vote, and into Prohibition. PRJC President: Mary Doyle Documented — recorded live! (703) 280-2373 April 13. Host Sonny McGown. "Bobby Vice President: Ken Kramer Hackett" — tracing the career of this famous (703) 354-7844 cometist/trumpeter from 1938. TAILGATE RAMBLINGS is the monthly publication April 20. Host Nat Kinnear. "Pioneers in o f the Potomac River Jazz Club. The Club T ra d itio n a l J a z z ," the h is to ry o f the stands for the preservation, encouragement, Original Dixieland Jass Band. and advancement o f trad ition al jazz. This means jazz from 1900 to 1930 in the New A p ril 27. Host Lou Byers. "W ild B i ll Orleans, Chicago, and Dixieland styles, Davison," a potpourri of his most famous including their various revivals, as well as recording dates and best known sessions. blues and ragtime. TAILGATE RAMBLINGS welcomes contributions from its readers. GREETINGS FROM THE PRESIDENT At the regular PRJC board meeting on the It was announced that Burt Bales, a third Wednesday of the month, the board heard well-known West Coast jazz pianist who made an oral report on the Jazzathon. -

From the Boardwalk to the Birchwood 42Ndpee WEE Russell Memorial Stomp March 6 New Jerseyjazzsociety in This Issue: NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Prez Sez

Volume 39 • Issue 2 February 2011 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Fresh off their star turn in HBO’s Boardwalk Empire, Vince Giordano & the Nighthawks return to headline the 42nd Annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp on March 6 Story on page 24 From the Boardwalk to the Birchwood 42ndPEE WEE Russell Memorial Stomp March 6 New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Crow’s Nest. 4 Jazz Trivia . 4 Prez Sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 By Laura Hull President, NJJS New/Renewed Members . 43 Change of Address/Support e hit the ground running with jazz in Summit, NJ 07901. Tickets: $25 for NJJS NJJS/Volunteer/JOIN NJJS . 43 WJanuary and there is certainly no shortage members, $30 for non-members, $10 for students. STORIES of live jazz scheduled in February! We may be ■ Also on sale are tickets for An Afternoon of Jazz Journeys . 4 out of the holiday spirit here at NJJS but the Jazz, March 27 at the Morristown Community Big Band in the Sky. 8 spirit of jazz is always singing in our ears. Theatre. The charming and entertaining vocalist Talking Jazz: Amos Kaune. 14 ■ 42nd Annual Pee Wee Russell We heard from talented author Will Friedwald Antoinette Montague will delight us with music Memorial Stomp March 6 . 24 at the January Jazz Social and we look forward from her new CD release, Behind the Smile. Noteworthy . 28 to our Intimate Portrait Series returning on Antoinette, a native of Newark, is a dynamo with Martin Luther King, Jr.