OEC Fanfare Clarke Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Oceans Eat Cities

NEIL ROLNICK Credits Oceans Eat Cities Erik Peterson, recording engineer Sheldon Steiger, post-production and mastering engineer Deal With The Devil was recorded Nov 20, 2018 at Metropolitan State University, Denver, CO. Oceans Eat Cities and Mirages were recorded July 14 & 17, 2019 at Western Colorado University, Gunnison, CO. Cover image: Luke DuBois and Emilio Hernandez Cortes Photo credit: Chloe Bland All works are published by Neilnick Music (BMI) WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1857 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 Jennifer Choi, violin | Kathleen Supové, piano | VOXARE String Quartet TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2021 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Composer Rolnick was sidelined for most of 2018, caring for his wife of 45 years who Composer Neil Rolnick pioneered the use of computers in passed away that summer. In early 2019 he commemorated her memory with musical performance, beginning in the late 1970s. Based in a solo laptop piece, Messages, which repurposes her phone messages from New York City since 2002, his music has been performed before and during her illness. worldwide, including recent performances in Cuba, China, Between 2014 and 2018 Rolnick completed Declaration, Deal With The Korea, Mexico and across the US and Europe. His music Devil, Mirages, Oceans Eat Cities, Cello Ex Machina, Silicon Breath, Dynamic has appeared on 21 LPs, CDs and digital releases. His RAM & Concert Grand, and two solo laptop performance pieces, O Brother! string quartet Oceans Eat Cities was performed at the UN and WakeUp. -

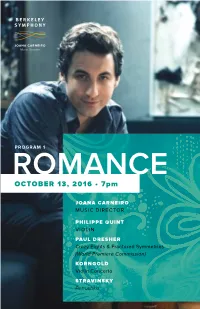

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

Graduate Catalog 2010–11 Mills College Graduate Catalog 2010Ð11

Graduate Catalog 2010–11 Mills College Graduate Catalog 2010–11 This catalog provides information on graduate admission and financial aid, student life, and academic opportunities for graduates at Mills College. Information for undergraduate students is provided in a separate Undergraduate Catalog. This catalog is published by: Mills College 5000 MacArthur Blvd. Oakland, CA 94613 www.mills.edu Cover photo: Nic Lehoux Table of Contents Mills College . 3 Education. 26 Accreditation . 3 Early Childhood Education . 28 Administration of Programs. 3 Master of Arts in Education Nondiscrimination Statement. 3 with an Emphasis in Early Childhood Education . 28 Student Privacy Rights. 3 Master of Arts in Education with Campus Photography . 3 an Emphasis in Leadership in Student Graduation and Persistence Rates. 3 Early Childhood . 28 Doctor of Education in Leadership with Academic Calendar . 4 an Emphasis in Early Childhood . 29 Master of Arts in Education About Mills College . 6 with an Emphasis in Child Life Overview . 6 in Hospitals . 29 Faculty . 6 Early Childhood Special Education Credential Program. 29 Academic Environment . 7 Educational Leadership . 30 Campus Resources . 7 Administrative Services Credential . 30 Graduate Housing. 7 Master of Arts in Education . 30 History . 8 Doctor of Education . 31 Studio Art . 9 Teacher Preparation . 31 Multiple Subjects Credential with Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art . 10 an Early Childhood Emphasis . 31 Courses. 10 Multiple Subjects Credential . 32 Single Subject Credential: Art, English, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 12 Foreign Language, or Social Studies . 32 Certificate Program . 13 Single Subject Credential: Math or Science . 32 Computer Science. 14 Master of Arts in Education with Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary an Emphasis in Teaching (MEET) . -

MUSICAL ELEMENTS: SHINING a LIGHT on MIDTOWN by Blake

Musical Elements: Shining a Light on Midtown Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Cesarz, Blake Edward Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 18:50:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/622899 MUSICAL ELEMENTS: SHINING A LIGHT ON MIDTOWN by Blake Edward Cesarz ____________________________ Copyright © Blake Edward Cesarz 2016 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled Musical Elements: Shining a Light on Midtown prepared by Blake Edward Cesarz has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Rolnick 500 Word Bio 2020

Neil Rolnick 870 West 181st St., Apt 63 email: [email protected] New York, NY 10033 USA cell: (917)848-3008 Composer Neil Rolnick pioneered the use of computers in musical performance, beginning in the late 1970s. Based in New York City since 2002, his music has been performed world wide, including recent performances in Cuba, China, Korea, Mexico and across the US and Europe. His string quartet Oceans Eat Cities was performed at the UN Global Climate Summit in Paris in Dec. 2015. In 2016 and 2017 he was awarded an ArtsLink residency in Belgrade, Serbia, a New Music USA Project Grant and an artist residency at the Bogliasco Foundation near Genoa, Italy. In 2019 he received an Individual Artist Grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, for a new work for pianist Geoff Burleson. In early 2020 he was featured at the Primavera en la Habana festival in Cuba. Rolnick’s music often explores combinations of digital sampling, interactive multimedia, and acoustic vocal, chamber and orchestral works. In the 1980s and ‘90s he developed the first integrated electronic arts graduate and undergraduate programs in the US, at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s iEAR Studios, in Troy, NY. Rolnick’s innovation as an educator was to bring together the commonality of artistic creation across many disciplines, and this led to his varied work with filmmakers, writers, and video and media artists. Though much of Rolnick’s work has been in areas which connect music and technology, and is therefore considered in the realm of “experimental” music, his music has always been highly melodic and accessible. -

Rolnick Bio 2021

Neil Rolnick 870 West 181st St., Apt 63 email: [email protected] New York, NY 10033 USA cell: (917)848-3008 Composer Neil Rolnick pioneered in the use of computers in musical performance, beginning in the late 1970s. Based in New York City since 2002, his music has been performed world wide, including recent performances in Cuba, China, Mexico and across the US and Europe. His string quartet Oceans Eat Cities was performed at COP21, the UN Global Climate Summit in Paris in Dec. 2015. In 2016 and 2017 he was awarded an ArtsLink Grant for a residency in Belgrade, Serbia, a New Music USA Project Grant and an artist residency at the Bogliasco Foundation’s Liguria Study Center near Genoa, Italy. In 2019 he received an Individual Artist Grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, through the Tribeca New Music Festival, for a new work for pianist Geoff Burleson. In 2020 he was featured at the Primavera en la Habana festival in Cuba, just before the city was closed by COVID-19. In 2021 a new work for streaming media will be premiered by Ensemble Échappé. Rolnick’s music often explores combinations of digital sampling, interactive multimedia, and acoustic vocal, chamber and orchestral forces. In the 1980s and ‘90s he developed the first integrated electronic arts graduate and undergraduate programs in the US, at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s iEAR Studios, in Troy, NY. Rolnick’s innovation as an educator has been to bring together the commonality of artistic creation across many disciplines, and this has led to his varied work with filmmakers, writers, and video and media artists. -

THE DEPARTMENT of MUSIC STATE UNIVERSITY of NEW YORK at BUFFALO a

THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO a ,-.-.. r -Â¥-^-- presented by L- ._;TMENT OF MUSIC/STATE UNIVERSITV OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO April 7 - April 14, 1984 JAN WILLIAMS. YVAR MIKHASHOFF. LEJAREN HILLER. CO-DIRECTORS BERNADETTE SPEACH. MANAGING DIRECTOR PROGRAM INDEX PAGE concert THE EUROPEAN NEWMUSICSCENE encounter I/- MUSIC OF FRANK ZAPPA concert MUSIC OF FELDMAN AND MARCUS encounter, concert AFTER HOURS CABARET: EVOCATIONS concert -1 \ NEW FROM NEW YORK..A.: - encounter, concert AFTER HOURS CABARET: INTEGRATIONS concert -' * %5 MUSIC AND THE COMPUTER I a. encounter, concert - -* MUSIC AND THE COMPUTER II encounter, concert AFTER HOURS CABARET: CONTEMPLATIONS concert HILLER-BABBITT COLLAGE - encounter, concert . -^% ." - .' PIANOPERCUSSION EXTRAVAGANZA ,. *< concert Practically from the moment of the founding of the U.B. Music Department by Cameron Baird in 1 953, the creation, performance and study of contemporary music have been integral components of its diverse programs for both students and the public at large. This second North American New Music Festival confirms and reaffirms our commitment to new music here at UB: building on tradi- tion while chronicling today's avant-garde. The task of planning this Festival was made immeasurably easier by the ex~erienceaained from its highly successful antecedents - the Center of the creative and performing ~rtsancfthe ~unein Buffalo Festival. From the residency of Aaron Cooland as the first Slee Professor of Comoosition in 1957, through the 17-year history of the Center - which ended in 1980-the interactionof COG- poser and performer has been our focus; so it is with this new venture as well. -

Electronic Music Midwest 16Th Annual Festival Providing Access to New

16th Annual Festival Electronic Music Midwest October 13-15, 2016 Lewis University Providing access to new electroacoustic music by living composers October 13-15, 2016 Lewis University Romeoville, IL October 13, 2016 Dear Friends, Welcome to the 16th Annual Electronic Music Midwest! We are truly excited about our opportunity to present this three-day festival of electroacoustic music. Over 200 works were submitted for consideration for this year’s festival. Congratulations on your selection! Since 2000, our mission has been to host a festival that brings new music and innovative technologies to the Midwest for our students and our communities. We present this festival to offer our students and residents a chance to interact and create a dialog with professional composers. We are grateful that you have chosen to help us bring these goals to fruition. We are grateful to Sarah Plum for serving as our artist in residence this year. Sarah is an outstanding performer who is a champion of new music. We are confident you will be impressed by her performances throughout the festival. The 2016 EMM will be an extraordinary festival. If only for a few days, your music in this venue will create a sodality we hope continues for a long time to follow. Your contribution to this festival gives everyone in attendance insight into the future of this ever developing field of expression. We are delighted that you have chosen to join us this year at EMM, and we hope that you have a great time during your stay. If we can do anything to make your experience here better, please do not hesitate to ask any of the festival team. -

Other Minds Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8wq0984 Online items available Guide to the Other Minds Records Alix Norton, Jay Arms, Madison Heying, Jon Myers, and Kate Dundon University of California, Santa Cruz 2018 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Guide to the Other Minds Records MS.414 1 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Other Minds records Creator: Other Minds (Organization) Identifier/Call Number: MS.414 Physical Description: 399.75 Linear Feet (404 boxes, 15 framed and oversized items) Physical Description: 0.17 GB (3,565 digital files, approximately 550 unprocessed CDs, and approximately 10 unprocessed DVDs) Date (inclusive): 1918-2018 Date (bulk): 1981-2015 Language of Material: English https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f1zk5ftt Access Collection is open for research. Audiovisual media is unavailable until reformatted. Digital files are available in the UCSC Special Collections and Archives reading room. Some files may require reformatting before they can be accessed. Technical limitations may hinder the Library's ability to provide access to some digital files. Access to digital files on original carriers is prohibited; users must request to view access copies. Contact Special Collections and Archives in advance to request access to audiovisual media and digital files. Publication Rights Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. -

Other Minds 13 Program

Other Minds Festival of New Music March 6–8, 2008 Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Guest Composers Michael Bach Dan Becker Elena Kats-Chernin Keeril Makan Åke Parmerud Dieter Schnebel Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith Morton Subotnick Frances-Marie Uitti Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director 34 12 16 B 7 19 15 A 2 36 1 Other Minds, in association with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and the Eugene and Elinor Friend Center for the Arts at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, presents Other Minds 13 Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director Jewish Community Center of San Francisco March 6-7-8, 2008 Table of Contents 3 Message from the Artistic Director 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction 6 Concert 1 7 Concert 1 Program Notes 10 Concert 2 11 Concert 2 Program Notes 14 Concert 3 15 Concert 3 Program Notes 20 Other Minds 13 Composers 24 About Other Minds Other Minds 13 Festival Staff 25 Other Minds 13 Performers 28 Festival Supporters A Gathering of Other Minds Program Design by Leigh Okies. Layout and editing by Adam Fong. © 2008 Other Minds. All Rights Reserved. The Djerassi Resident Artists Program is a proud co-sponsor of Other Minds Festival XIII The mission of the Djerassi Resident Artists Program is to support and enhance the creativity of artists by providing uninterrupted time for work, reflection, and collegial interaction in a setting of great natural beauty, and to preserve the land upon which the Program is situated. The Djerassi Program annually welcomes the Other Minds Festival composers for a five-day residency for collegial interaction and preparation prior to their concert performances in San Francisco. -

Touching Down in China

“I can't imagine that many of them really knew what Neil Rolnick’s music is similar to his personality, showing a kind of music they were coming in to hear, but they comfortable and unflashy expertise with lyricism and virtuo- certainly convinced me by their responses that they sic writing but touching on unorthodox electroacoustic ele- were eager to hear new things,” ments such as melody, rhythm and even humor. Through his unconventional use of sonic materials and convergent me- says Rolnick when describing his audience at a recent per- dia, he also integrates live performance, collaborative forces formance in Beijing. and improvisation to create a unique sound inspired by his I first met Neil Rolnick at Visiones Sonoras 2006, where I interactions with various musical cultures of the world. discovered his tremendous musical voice and a warm, en- gaging personality. He is also great listener off-stage, taking just as much care to learn from a discussion as he does to contribute to it. After attending his talk at Visiones Sonoras 2008, One Month and One Ear in China, I was intrigued by his interactions in the Conservatories and musical under- ground of such a diametrically opposed culture, and decided to continue the discussion with him the weeks following. The Economic Engine @ DEJ08, 798 Art Area Touching down in China: These days, Neil is a savvy world citizen using his music as a passport. A quick glance at his resume showing tra- vels around the globe with performances in such places as Japan, Mexico Reykjavik, Yugoslavia, and Zurich.