Stormwater and Flooding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Stormwater Runoff from Development by Robert Pitt, P.E

A River Network Publication Volume 14 | Number 3 - 2004 Effects of Stormwater Runoff from Development By Robert Pitt, P.E. Ph.D., University of Alabama ost people know that urban runoff is a problem, but very few realize just how harmful it can be for rivers, lakes and streams. In order to secure better control of urban runoff, we must make the public and its officials aware of the full extent of the problems that need to be prevented when new M development takes place. Urban runoff has been found to cause significant impacts on aquatic life. The effects are obviously most severe for waters draining heavily urbanized watersheds. However, some studies have shown important aquatic life impacts even for streams in watersheds that are less than ten percent urbanized. Most aquatic life impacts associated with urbanization are probably related to long- term problems caused by polluted sediments and food web disruption. Because ecological responses to watershed changes may take between 5 and 10 years to equilibrate, water monitoring conducted soon after disturbances or mitigation may not accurately reflect the long-term conditions that will eventually occur. The first changes due to urbanization will be to stream and groundwater hydrology, followed by fluvial morphology, then water quality, and finally the aquatic ecosystem. Effects of Stormwater Discharges on Aquatic Life Many studies have shown the severe detrimental effects of urban runoff on water Photo courtesy of Dr. Pitt organisms. These studies have generally examined receiving water conditions above and below a city, or by comparing two parallel streams, one urbanized and another nonurbanized. -

Stormwater Management Regulations

City of Waco Stormwater Management Regulations 1.0 Applicability: These regulations apply to all development within the limits of the City of Waco as well as to any subdivisions within the extra territorial jurisdiction of the City of Waco. Any request for a variance from these regulations must be justified by sound Engineering practice. Other than those variances identified in these regulations as being at the discretion of the City Engineer, variances may only be granted as provided in the Subdivision Ordinance of the City of Waco or Chapter 28 – Zoning, of the Code of Ordinances of the City of Waco, as applicable. 1.1 Definitions: 100 year Floodplain Area inundated by the flood having a one percent chance of being exceeded in any one year (Base Flood). (Also known as Regulatory Flood Plain) Adverse Impact: Any impact which causes any of the following: Any increased inundation, of any building structure, roadway, or improvement. Any increase in erosion and/or sedimentation. Any increase in the upstream or downstream floodplane level. Any increase in the upstream or downstream floodplain boundaries. Floodplane The calculated elevation of floodwaters caused by the flood Elevation of a particular frequency. Drainage System System made up of pipes, ditches, streets and other structures designed to contain and transport surface water generated by a storm event. Treatment Removal/partial removal of pollutants from stormwater. Watercourse a natural or manmade channel, ditch, or swale where water flows either continuously or during rainfall events 1.2 Adverse Impact No preliminary or final plat or development plan or permit shall be approved that will cause an adverse drainage impact on any other property, based on the 2 yr, 10 1 yr, 25 yr and 100 yr floods. -

2013 Stormwater Status Report

2013 Fairfax County � STORMWATER STATUS REPORT � A Fairfax County, Va., publication � June 2014 � Photos on cover (from top left): Fish sampling; Wolftrap Creek stream restoration in Vienna, VA; Fish – small mouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu) at Water Quality Field Day; Sampling station being serviced — Occoquan; Water Quality Field Day – Woodley Hills School; Tree planting; Stormwater Management Pond – Noman M. Cole, Jr., Pollution Control Plant. (photo credit Fairfax County) i Report prepared and compiled by: Stormwater Planning Division Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Fairfax County, Virginia 22035 703-324-5500, TTY 711 www.fairfaxcounty.gov/dpwes/stormwater June 2014 To request this information in an alternate format call 703-324-5500, TTY 711. Fairfax County is committed to nondiscrimination on the basis of disability in all county programs, services and activities. Reasonable accommodations will be provided upon request. For information, call 703-324-5500, TTY 711. ii This page was intentionally left blank. iii iv Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... vi List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgments -

Problems and Solutions for Managing Urban Stormwater Runoff

Rained Out: Problems and Solutions for Managing Urban Stormwater Runoff Roopika Subramanian* The Clean Water Rule was the latest attempt by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers to define “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act. While both politics and scholarship around this issue have typically centered on the jurisdictional status of rural waters, like ephemeral streams and vernal pools, the final Rule raised a less discussed issue of the jurisdictional status of urban waters. What was striking about the Rule’s exemption of “stormwater control features” was not that it introduced this urban issue, but that it highlighted the more general challenges of regulating stormwater runoff under the Clean Water Act, particularly the difficulty of incentivizing multibenefit land use management given the Act’s focus on pollution control. In this Note, I argue that urban stormwater runoff is more than a pollution-control problem. Its management also dramatically affects the intensity of urban water flow and floods, local groundwater recharge, and ecosystem health. In light of these impacts on communities and watersheds, I argue that the Clean Water Act, with its present limited pollution- control goal, is an inadequate regulatory driver to address multiple stormwater-management goals. I recommend advancing green infrastructure as a multibenefit solution and suggest that the best approach to accelerate its adoption is to develop decision-support tools for local government agencies to collaborate on green infrastructure projects. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 422 I. Urban Stormwater Runoff .................................................................... 424 A. Urban Stormwater Runoff: Multiple Challenges ........................... 425 B. Urban Stormwater Infrastructure Built to Drain: Local Responses to Urban Flooding ....................................................... -

Stormwater from Kc to the Sea

stormwater from kc to the sea A 5-day Workshop for Students in the 4th - 6th Grades TEACHER’S GUIDE contents introduction 1 day one : It’s an Event 3 learning objectives 4 background 5 procedure 6 discussion questions 7 day two : Dangerous Travel 13 learning objectives 14 background 15 procedure 16 discussion questions 19 day three : Cleaning up (our Water) Act 21 learning objectives 22 background 23 procedure 26 discussion questions 27 day four : Those Traveling Stormwater Teams 29 learning objectives 30 background 31 procedure 32 discussion questions 33 day five : Walking the Talk 35 learning objectives 36 background 37 procedure 38 discussion questions 39 vocabulary 40 stormwater ~ from kc to the sea introduction The Water Services Department of Kansas City, Missouri believes good water quality is everybody’s business. The agency is providing this curriculum for students, and ultimately their parents and the community, to become aware of one aspect of our City’s water – the treatment of stormwater. This guide addresses that topic and is aligned with Common Core State Standards and New Generation Science Standards for students in the 4th and 5th grades. We see that 6th grade standards would be more advanced yet similar should 6th grade instructors wish to use this curriculum.Through five interactive and fun days, students will learn how precipitation moves through the watershed and how to measure rainfall amounts; they will learn to demonstrate how water becomes polluted and determine how best management practices (BMPs) improve the quality and quantity of our water; they will also locate current BMPs in their community, design the ideal street, and create a public service announcement, brochure or poster that persuades people to follow BMPs in their treatment of this valuable resource. -

A Practical Guide to Implementing Integrated Water Resources Management and the Role for Green Infrastructure”, J

A Practical Guide to Implementing Integrated Water Resources Management & the Role of Green Infrastructure Prepared for: Prepared for: Funded by: Prepared by: May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Environmental Consulting & Technology, Inc. (ECT), wishes to extend our sincere appreciation to the individuals whose work and contributions made this project possible. First of all, thanks are due to the Great Lakes Protection Fund for funding this project. At Great Lakes Commission, thanks are due to John Jackson for project oversight and valuable guidance, and to Victoria Pebbles for administrative guidance. At ECT, thanks are due to Sanjiv Sinha, Ph.D., for numerous suggestions that helped improve this report. Many other experts also contributed their time, efforts, and talent toward the preparation of this report. The project team acknowledges the contributions of each of the following, and thanks them for their efforts: Bill Christiansen, Alliance for Water Efficiency James Etienne, Grand River Conservation Christine Zimmer, Credit Valley Conservation Authority Authority Cassie Corrigan, Credit Valley Conservation Melissa Soline, Great Lakes & St. Lawrence Authority Cities Initiative Wayne Galliher, City of Guelph Clifford Maynes, Green Communities Canada Steve Gombos, Region of Waterloo Connie Sims – Office of Oakland County Water Julia Parzens, Urban Sustainability Directors Resources Commissioner Network Dendra Best, Wastewater Education For purposes of citation of this report, please use the following: “A Practical Guide to Implementing -

The Causes of Urban Stormwater Pollution

THE CAUSES OF URBAN STORMWATER POLLUTION Some Things To Think About Runoff pollution occurs every time rain or snowmelt flows across the ground and picks up contaminants. It occurs on farms or other agricultural sites, where the water carries away fertilizers, pesticides, and sediment from cropland or pastureland. It occurs during forestry operations (particularly along timber roads), where the water carries away sediment, and the nutrients and other materials associated with that sediment, from land which no longer has enough living vegetation to hold soil in place. This information, however, focuses on runoff pollution from developed areas, which occurs when stormwater carries away a wide variety of contaminants as it runs across rooftops, roads, parking lots, baseball diamonds, construction sites, golf courses, lawns, and other surfaces in our City. The oily sheen on rainwater in roadside gutters is but one common example of urban runoff pollution. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) now considers pollution from all diffuse sources, including urban stormwater pollution, to be the most important source of contamination in our nation's waters. 1 While polluted runoff from agricultural sources may be an even more important source of water pollution than urban runoff, urban runoff is still a critical source of contamination, particularly for waters near cities -- and thus near most people. EPA ranks urban runoff and storm-sewer discharges as the second most prevalent source of water quality impairment in our nation's estuaries, and the fourth most prevalent source of impairment of our lakes. Most of the U.S. population lives in urban and coastal areas where the water resources are highly vulnerable to and are often severely degraded by urban runoff. -

Victory Farm Stormwater Management and Stream Stabilization January 21St, 2021 Public Meeting

Victory Farm Stormwater Management and Stream Stabilization January 21st, 2021 Public Meeting City of Gaithersburg Department of Public Works, Environmental Services Division Agenda o Introductions o Background o Watershed Basics 1 2 3 4 o MS4 Basics (Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System) o City Funding o Drainage Area Characteristics o Project Goals o Water Quality vs. Water Quantity o Stable watercourse o Environmental Stewardship o Safety o Community Involvement o Project Design o Three part design o Type of facility o Features and purpose o Priority Considerations o Associated Improvements o Next Steps o Exit Survey Introductions City of Gaithersburg Pearce Wroe, P.E. Stormwater Project Manager Mike Weyand Watershed Specialist Engineering Consultant, CPJ & Associates, Inc. Robyn Barnhart, P.E. Section Head, Public Sector Division Introductions: Who are you? Chesapeake Bay Watershed Maryland’s Watershed Basins Maryland’s 8 Digit Watershed Maryland’s 8 Digit Watershed & City of Gaithersburg Maryland’s 12 Digit Watersheds Next Slide Watershed Basics Victory Farm Pond Drainage Area ~450 Acres Watershed Basics o Water flows downhill o A Watershed is; o “a region or area bounded peripherally by a divide and draining ultimately to a particular watercourse or water body” – Merriam-Webster o An area where all of water drains to the same place o Scales of Watersheds o Chesapeake Bay o Local watersheds – Seneca Creek, Muddy Branch, Rock Creek o Sub Local watersheds – Middle Seneca Creek - Whetstone Run o Project Level Watersheds – We’ll call -

Charles River Stormwater Permitting: Agency Residual Designation Review

Charles River Stormwater Permitting Agency Residual Designation Review - Process Overview Presentation EPA Region 1 – New England September 2020 Webinar Outline • Charles River watershed overview • Water Quality Standards & Pollution Sources • Clean Water Act discussion • 2019 Residual Designation petition summary • Plan for EPA Engagement in 2020 & 2021 CHARLES RIVER: INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW Ken Moraff Water Division Director EPA Region 1 Charles River Watershed o 80-mile river - Hopkinton to Boston Harbor o Drainage area - 310 square miles o 35 municipalities Human Uses • Upper Charles • Recreational Boating • Fishing • Lower Charles • Recreational Boating • Sailing and Rowing Clubs • Swimming* • Public Events Photos: epa.gov/charlesriver Clean Water Act History of Success o Significant Reduction in Sewer Overflows o 2003 Municipal Stormwater General Permit (2016 and 2020 updates) o Removal of illegal sewage discharges into storm drains o 2020’s 25th Anniversary Charles River “Report Card” Photo: wikimedia Progress has been made; however, work remains • Progress on Bacteria • Reduced sewer overflows • Stormwater improvements • Need to Reduce Phosphorus • Phosphorus triggers algal blooms - some are toxic • MA and EPA set reduction targets • Municipal wastewater plants have achieved a 90%+ reduction • Biggest remaining source is stormwater – municipalities reducing, but private property is a large source Where Do We Go From Here? • Solve algae/phosphorus problem • Respond to petition • Stakeholder input Photos: epa.gov,, epa.gov, neiwpcc.orghttps://neiwpcc.org/our-programs/wetlands-aquatic-species/habs/ -

Stormwater Management and Sediment and Erosion Control Plan Review Checklist for Design Professionals

Stormwater Management and Sediment and Erosion Control Plan Review Checklist For Design Professionals This Plan Review Checklist for Design Professionals has been developed to aid those who prepare Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plans (SWPPPs). Adjacent to the heading for most sections are references from the corresponding portion of the NPDES General Permit for Stormwater Discharges from Construction Activities (SCR100000), which was issued on October 15, 2012. SWPPP Preparers should not utilize this checklist as a substitute for the language in the permit and should review the permit itself for more information on each specific requirement. The permit may be found at: http://www.scdhec.gov/environment/water/swater/docs/CGP-permit.pdf In the space provided please indicate the location and page number(s) where each item below can be found in your SWPPP or supporting calculations. If an item is not applicable, put N/A. The Department reserves the right to modify this checklist at any time. The Coastal Zone consists of the following counties: Beaufort, Berkeley, Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Georgetown, Horry, and Jasper. *Revised Items in Red Project Information: Project Name: County: Checklist Completed by: Printed name: ___________________________ Signature: ___________________________ Date:___________ PLANS AND MAPS 1. CURRENT COMPLETED APPLICATION FORM ● Original Signature of individual with signatory authority for the applicant according to requirements set forth in R.61-9.122.22 (see Appendix C) ● All items completed and answered -

Overview of Stormwater Effects on Water Quality 2 What Is Urban Stormwater?

OiOverview o f Stormwa ter Effects on Water Quality wq-strm7-81 Stormwater Module 1 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Training goals Recognize the wide Identify how land variety of use, management pollutants in urban practices, and stormwater runoff natural factors that can impair affect pollutant receiigiving waters ldigloading Stormwater module 1: Overview of stormwater effects on water quality 2 What is urban stormwater? Water running off an urban land surface after a rainfall or snowmelt event Stormwater module 1: Overview of stormwater effects on water quality 3 Urban areas have less infiltration and evaporation and more runoff than forested or grassland areas Two most important factors: 1. amount of impervious surface 2. connectedness of impervious surface Source for figure: http://duluthstreams.org/understanding/stormwater_hydrology.html Stormwater module 1: Overview of stormwater effects on water quality 4 How do we affect the quality of stormwater? Chemicals that we apply to the ldlandscape are carr idied with runoff water to receiving waters Stormwater module 1: Overview of stormwater effects on water quality 5 What environmental effects are associated with stormwater runoff? Stormwater usually discharges to a lake, river/stream or wetland Increased runoff may cause flooding Chem ica ls may be tox ic to organisms Characteristics (habitat) of the receiving water body mayyg change Stormwater module 1: Overview of stormwater effects on water quality 6 What water body impairments are associated with stormwater? nutrients (primarily -

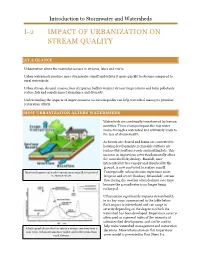

Introduction to Stormwater and Watersheds I-2 IMPACT of URBANIZATION on STREAM QUALITY

Introduction to Stormwater and Watersheds I-2 IMPACT OF URBANIZATION ON STREAM QUALITY AT A GLANCE Urbanization alters the natural processes in streams, lakes and rivers. Urban watersheds produce more stormwater runoff and deliver it more quickly to streams compared to rural watersheds. Urban stream channel erosion, loss of riparian buffers warmer stream temperatures and toxic pollutants reduce fish and aquatic insect abundance and diversity. Understanding the impacts of imperviousness on stream quality can help watershed managers prioritize restoration efforts. HOW URBANIZATION ALTERS WATERSHEDS Watersheds are continually transformed by human activities. These changes impact the way water moves through a watershed and ultimately leads to the loss of stream health. As forests are cleared and farms are converted to housing developments, permeable surfaces are replaced by rooftops, roads and parking lots. This increase in impervious cover fundamentally alters the watershed’s hydrology. Rainfall, once intercepted by tree canopy and absorbed by the ground, is now converted to surface runoff. Increased impervious surface means more rainfall is converted Consequently, urban streams experience more to surface runoff. frequent and severe flooding. Meanwhile, stream flow during dry weather often declines over time because the groundwater is no longer being recharged. Urbanization significantly impacts stream health in six key ways, summarized in the table below. Each impact is interrelated and can range in severity depending on the degree to which the watershed has been developed. Impervious cover is often used as a general index of the intensity of subwatershed development, and can be used to help make watershed management and restoration A hydrograph shows the flow rate in a stream over time after a rain event.