Torts. Manufacturer's Liability. Intervening Negligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

Chapter 668 Liability in Tort — Comparative Fault

1 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT, §668.3 CHAPTER 668 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT Referred to in §321J.4B, 625.21 668.1 Fault defined. 668.11 Disclosure of expert witnesses 668.2 Party defined. in liability cases involving 668.3 Comparative fault — effect — licensed professionals. payment method. 668.12 Liability for products — defenses. 668.4 Joint and several liability. 668.13 Interest on judgments. Evidence of previous payment or 668.5 Right of contribution. 668.14 future right of payment. 668.6 Enforcement of contribution. 668.14A Recoverable damages for medical 668.7 Effect of release. expenses. 668.8 Tolling of statute. 668.15 Damages resulting from sexual 668.9 Insurance practice. abuse — evidence. 668.10 Governmental exemptions. 668.16 Applicability of this chapter. 668.1 Fault defined. 1. As used in this chapter, “fault” means one or more acts or omissions that are in any measure negligent or reckless toward the person or property of the actor or others, or that subject a person to strict tort liability. The term also includes breach of warranty, unreasonable assumption of risk not constituting an enforceable express consent, misuse of a product for which the defendant otherwise would be liable, and unreasonable failure to avoid an injury or to mitigate damages. 2. The legal requirements of cause in fact and proximate cause apply both to fault as the basis for liability and to contributory fault. 84 Acts, ch 1293, §1 See also §619.17 668.2 Party defined. As used in this chapter, unless otherwise required, “party” means any of the following: 1. -

Assumption of Risk, Waiver, and Release of Liability

Rev. 4/30/2020 ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER, AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY READ THIS ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY BEFORE YOU SIGN IT. IT AFFECTS YOUR LEGAL RIGHTS. I, ____________________________ [print student’s name], agree to act in a responsible and safe manner during my participation in the ____________________________ “the Program.” I acknowledge and agree that I must comply with the rules and requirements of the Program, any other applicable University policy, and all applicable local, state, and federal law. I agree to follow the instructions issued by Program directors and staff. I will also abide by signage posted on the University’s campus. I understand that I may be dismissed from the Program for misconduct. I understand that my participation in the Program is voluntary, and I may be exposed to risks and hazards that could result in serious illness, bodily injury, disability, or death. These risks and hazards may include, but are not limited to: (i) vehicular, pedestrian, or other accidents, such as drowning, (ii) storms, floods, fires, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, (iii) infectious diseases or viruses, including but not limited to COVID-19, (iv) limited or inadequate medical care, (v) inadequate design, safety, and maintenance of buildings and public places, (vi) terrorist activities, and (vii) allergic reactions to food, insects, or other allergens. I also understand that during the Program I may use or access educational computer applications, web-based services, or online content that could expose me to certain cyber risks, including but not limited to, cyber predators, data mining, phishing, viruses, malware, data breaches, cyberbullying, exploitation, victimization, cyber stalking, online grooming, reputational loss, brand hijacking, and image replication. -

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Basis of Tort Law 3. Intentional Torts 4. Negligence 5. Cyber Torts: Defamation Online 6. Strict Liability 7. Product Liability 8. Defenses to Product Liability 9. Tort Law and the Paralegal Chapter Objectives After completing this chapter, you will know: • What a tort is, the purpose of tort law, and the three basic categories of torts. • The four elements of negligence. • What is meant by strict liability and under what circumstances strict liability is applied. • The meaning of strict product liability and the underlying policy for imposing strict product liability. • What defenses can be raised in product liability actions. Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline I. INTRODUCTION A. Torts are wrongful actions. B. The word tort is French for “wrong.” II. THE BASIS OF TORT LAW A. Two notions serve as the basis of all torts. i. Wrongs ii. Compensation B. In a tort action, one person or group brings a personal-injury suit against another person or group to obtain compensation or other relief for the harm suffered. C. Tort suits involve “private” wrongs, distinguishable from criminal actions that involve “public” wrongs. D. The purpose of tort law is to provide remedies for the invasion of various interests. E. There are three broad classifications of torts. i. Intentional Torts ii. Negligence iii. Strict Liability F. The classification of a particular tort depends largely on how the tort occurs (intentionally or unintentionally) and the surrounding circumstances. Intentional Intentions An intentional tort requires only that the tortfeasor, the actor/wrongdoer, intended, or knew with substantial certainty, that certain consequences would result from the action. -

Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory Into Tort Doctrine John L

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1991 Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine John L. Diamond UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John L. Diamond, Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine, 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Diamond John Author: John L. Diamond Source: Ohio State Law Journal Citation: 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Title: Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine Originally published in OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL. This article is reprinted with permission from OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL and Ohio State University Michael E. Moritz College of Law. Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine JOHN L. DIAMOND* I. INTRODUCTION The confusion generated by the doctrine of assumption of risk' is illustrated by the contradicting responses to the following hypothetical: - 0 1991 John L. Diamond. Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. B.A., Yale College; J.D., Columbia Law School; Dip. -

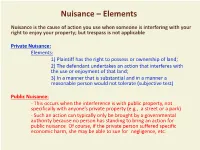

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk-- the Ac Se for Their Em Rger Minn

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1971 Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk-- The aC se for Their eM rger Minn. L. Rev. Editorial Board Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Editorial Board, Minn. L. Rev., "Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk--The asC e for Their eM rger" (1971). Minnesota Law Review. 2996. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2996 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Note: Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk- The Case for Their Merger I. INTRODUCTION At common law the plaintiff in a negligence action was barred from recovery when his conduct constituted either con- tributory negligence or assumption of risk. As a result of the adoption of a comparative negligence statute in Minnesota,' con- tributory negligence no longer completely bars recovery but only reduces recoverable damages. The statute, however, is silent as to assumption of risk. Since the purpose of the statute is to al- low a plaintiff to recover part of his damages despite the fact that his conduct fails to meet the reasonable man standard of care, as long as his negligence is less than that of the defendant, and since both contributory negligence and assumption of risk describe unreasonable conduct by the plaintiff, the purpose of the comparative negligence statute would be frustrated if assumption of risk continued to operate as a complete bar to recovery. -

Distinction Between Assumption of Risk and Contributory Negligence: Host and Guest Relationship (Page 182 Includes Editorial Board)

Marquette Law Review Volume 18 Article 3 Issue 3 April 1934 Torts: Distinction Between Assumption of Risk and Contributory Negligence: Host and Guest Relationship (Page 182 Includes Editorial Board). Aaron Horowitz Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Aaron Horowitz, Torts: Distinction Between Assumption of Risk and Contributory Negligence: Host and Guest Relationship (Page 182 Includes Editorial Board)., 18 Marq. L. Rev. 182 (1934). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol18/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW April, 1934 VOLUME XVIII MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN NUMBER THREE STUDENT EDITORIAL BOARD ROBERT P. HARLAND, Editor-in-Chief Carolyn E. Agger, Associate Parke G. Young, Associate Charles J. Curran Frank J. Antoine Russel J. Devitt Ernest 0. Eisenberg Gerrit D. Foster Carl W. Hofmeister Hugh F. Gwin Richard A. McDermott Aaron Horowitz Richard F. Mooney John C. Quinn Clemens H. Zeidler Clifford A. Randall BUSINESS STAFF ROBERT F. LARKIN, Business Manager OLIVER G. HAMILTON, Advertising ROBERT J. STOLTZ, Circulation FACULTY ADVISERS WILLIS E. LANG J. WALTER McKENNA VERNON X. MILLER Unless the LAW REVIEW receives notice to the effect that a subscriber wishes his subscription discontinued, it is assumed that a continuation is desired. An earnest attempt is made to print only authoritative matters. -

Tort Law - the Doctrine of Independent Intervening Cause Does Not Apply in Cases of Multiple Acts of Negligence - Torres V

Volume 30 Issue 2 Summer 2000 Summer 2002 Tort Law - The Doctrine of Independent Intervening Cause Does Not Apply in Cases of Multiple Acts of Negligence - Torres v. El Paso Electric Company Cynthia Loehr Recommended Citation Cynthia Loehr, Tort Law - The Doctrine of Independent Intervening Cause Does Not Apply in Cases of Multiple Acts of Negligence - Torres v. El Paso Electric Company, 30 N.M. L. Rev. 325 (2002). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol30/iss2/8 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr TORT LAW-The Doctrine of Independent Intervening Cause Does Not Apply in Cases of Multiple Acts of Negligence-Torres v. El Paso Electric Company I. INTRODUCTION In Torres v. El Paso Electric Company,' the New Mexico Supreme Court abolished the doctrine of independent intervening cause for multiple acts of negligence, including where a defendant and a plaintiff are both negligent.2 An independent intervening cause is "a cause which interrupts the natural sequence of events, turns aside their cause, prevents the natural and probable results of the original act or omission, and produces a different result, that could not have been reasonably foreseen."3 The Torrescourt concluded that the independent intervening cause instruction would "unduly emphasize" a defendant's attempts to shift fault and was "sufficiently repetitive" of that for proximate cause that -

Judging Plaintiffs Jason M

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2007 Judging Plaintiffs Jason M. Solomon Repository Citation Solomon, Jason M., "Judging Plaintiffs" (2007). Faculty Publications. 84. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/84 Copyright c 2007 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs Judging Plaintiffs Jason M. Solomon 60 Vand. L. Rev. 1749 (2007) With its powerful account of the normative principles embodied in the structure and practice of the law of torts, corrective justice is considered the leading moral theory of tort law. It has a significant advantage over instrumental and other moral theories in that it is more consistent with what judges say when they analyze tort law concepts. And with criticism of instrumental accounts, like law and economics, on a number of fronts, it is the leading descriptive theory of tort law. In this Article, I take up a question that has never been answered adequately by corrective-justice or other moral theorists: Why do we judge plaintiffs- their conduct, state of mind and other factors - to determine liability in tort law? This Article attempts to answer that question, and in doing so, shed light on contemporary theoretical, doctrinal, and practical debates about tort law. To do so, I first recast a variety of disparate doctrines in tort law as instances of a singular phenomenon-''judging-plaintiffs law''-and argue that existing explanations of this phenomenon fall short. Next, I suggest that judging-plaintiffs law can be explained and unified through a principle of self-help. -

Assumption of Risk in Sports

Assumption of Risk in Sports Assumption of Risk In New York State, when a person chooses to engage in or attend a sport or recreational activity, that individual “consents to those commonly appreciated risks which are inherent in and arise out of the nature of the sport generally and flow from such participation.” Fenty v. Seven Meadows Farms, Inc., No. 2012-05234, Slip op. at 1 (2d Dept 2013). The Assumption of Risk doctrine has traditionally been invoked by baseball teams when defending themselves from liability for fan injuries during games. It has been referred to as the “Baseball Rule.” It is common practice for teams to include boilerplate exculpatory language on their tickets that fans assume the inherent dangers of the sport when attending a game. Many lawsuits by fans throughout the years have been unsuccessful because of this affirmative defense. Lately, however, this doctrine is starting to be challenged, especially in the modern context of baseball and foul balls. New stadium designs have brought fans closer to the action, thus increasing the danger of being struck by errant foul balls. The game itself has also changed with the greater physicality and strength of the athletes resulting in harder hit balls. A. Assuming Risk when Applied to Recreational Activities Court of Appeals Bukowski v Clarkson Univ., 19 N.Y.3d 353, 948 N.Y.S.2d 568 (2012). A baseball player brought an action against Clarkson University after being hit by a line drive during an indoor practice . The plaintiff was an experienced baseball player and understood the risks that the game posed, especially on a pitcher, with it being common occurrences that line drives can cause injuries to pitchers. -

Torts--Intervening Cause--Liability of Original Tortfeasor for Subsequent Damages to Property by a Repairman

Volume 61 Issue 2 Article 16 February 1959 Torts--Intervening Cause--Liability of Original Tortfeasor for Subsequent Damages to Property by a Repairman A. G. H. West Virginia University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation A. G. H., Torts--Intervening Cause--Liability of Original Tortfeasor for Subsequent Damages to Property by a Repairman, 61 W. Va. L. Rev. (1959). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol61/iss2/16 This Case Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H.: Torts--Intervening Cause--Liability of Original Tortfeasor for Su CASE COMMENTS that the nature and extent of the risk are fully appreciated; and second, that it is voluntarily incurred. It was formerly confined by many courts to cases where a contractual relation existed. That limitation is generally no longer regarded." Thus, assumption of risk consists of a mental state of willingness and knowledge, whereas contributory negligence is a matter of conduct. Landrum v. Roddy, 148 Neb. 984, 12 N.W.2d 82 (1948); Peoples Drug Stores v. Windham, 178 Md. 172, 12 A.2d 532 (1940). Assumption of risk can arise out of contract by express agree- ment or may be implied from the action and conduct of the parties. As there was no contractual relation in the principal case, then if the defense existed it arose by implication.