The University of Hull Economic Growth in a Slave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 1 : Subject Catalogue

Volume 1 : Subject Catalogue 1 JAMAICAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 1962 - 2012 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF JAMAICA KINGSTON, JAMAICA 2013 i Published by: National Library of Jamaica P.O. Box 823 12 – 14 East Street Kingston Jamaica National Library of Jamaica Cataloguing in Publication Data Jamaican national bibliography 1962 -2012 p. ; cm. 1. Bibliography, National – Jamaica ISBN 978-976-8020-08-6 015.7292 – dc22 Copyright 2013by National Library of Jamaica ii T A B L E OF C O N T E N T S Preface………………………………………………………………………… iv Abbreviations and Terms……………………………………………………… v Sample Entries…………………………………………………………………. vi Outline of Dewey decimal classification……………………………….............. vii Classified Subject Listing………………………………………………………. 1 - 1014 iii PREFACE The mandate of the National Library of Jamaica is to collect, catalogue and preserve the nation’s publications and to make these items available for study and research. A related mandate is to compile and publish the national bibliography which is the list of material published in the country, authored by its citizens and about the country, regardless of place of publication. The occasion of Jamaica’s 50th anniversary was seen as an opportunity to fill in the gaps in the national bibliography which had been prepared sporadically: 1964 – 1969; 1975 – 1986; 1998- 2003; and so the Jamaican National Bibliography 1962-2012 (JNB 50) Volume 1 was created. Arrangement This volume of the bibliography is arranged according to the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) and catalogued using the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules. The information about an item includes the name the author uses in his/her works, the full title, edition, publisher, date of publication, number of pages, types of illustrations, series, size, notes, ISBN, price and binding. -

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

Update on Systems Subsequent to Tropical Storm Grace

Update on Systems subsequent to Tropical Storm Grace KSA NAME AREA SERVED STATUS East Gordon Town Relift Gordon Town and Kintyre JPS Single Phase Up Park Camp Well Up Park Camp, Sections of Vineyard Town Currently down - Investigation pending August Town, Hope Flats, Papine, Gordon Town, Mona Heights, Hope Road, Beverly Hills, Hope Pastures, Ravina, Hope Filter Plant Liguanea, Up Park Camp, Sections of Barbican Road Low Voltage Harbour View, Palisadoes, Port Royal, Seven Miles, Long Mountain Bayshore Power Outage Sections of Jack's Hill Road, Skyline Drive, Mountain Jubba Spring Booster Spring, Scott Level Road, Peter's Log No power due to fallen pipe West Constant Spring, Norbrook, Cherry Gardens, Havendale, Half-Way-Tree, Lady Musgrave, Liguanea, Manor Park, Shortwood, Graham Heights, Aylsham, Allerdyce, Arcadia, White Hall Gardens, Belgrade, Kingswood, Riva Ridge, Eastwood Park Gardens, Hughenden, Stillwell Road, Barbican Road, Russell Heights Constant Spring Road & Low Inflows. Intakes currently being Gardens, Camperdown, Mannings Hill Road, Red Hills cleaned Road, Arlene Gardens, Roehampton, Smokey Vale, Constant Spring Golf Club, Lower Jacks Hill Road, Jacks Hill, Tavistock, Trench Town, Calabar Mews, Zaidie Gardens, State Gardens, Haven Meade Relift, Hydra Drive Constant Spring Filter Plant Relift, Chancery Hall, Norbrook Tank To Forrest Hills Relift, Kirkland Relift, Brentwood Relift.Rock Pond, Red Hills, Brentwood, Leas Flat, Belvedere, Mosquito Valley, Sterling Castle, Forrest Hills, Forrest Hills Brentwood Relift, Kirkland -

San José Studies, November 1975

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1970s San José Studies 11-1-1975 San José Studies, November 1975 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_70s Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, November 1975" (1975). San José Studies, 1970s. 3. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_70s/3 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1970s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Portrait by Uarnaby Conrad (Courtesy of Steinbeck Research Center) John Steinbeck SAN JOSE STUDIES Volume I, Number 3 November 1975 ARTICLES Warren French 9 The "California Quality" of Steinbeck's Best Fiction Peter Lisca 21 Connery Row and the Too Teh Ching Roy S. Simmonds 29 John Steinbeck, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Edith McGillcuddy Martha Heasley Cox 41 In Search of John Steinbeck: His People and His Land Richard Astro 61 John Steinbeck and the Tragic Miracle of Consciousness Martha Heasley Cox 73 The Conclusion of The Gropes of Wroth: Steinbeck's Conception and Execution Jaclyn Caselli 83 John Steinbeck and the American Patchwork Quilt John Ditsky . 89 The Wayward Bus: Love and Time in America Robert E. Work 103 Steinbeck and the Spartan Doily INTERVIEWS Webster F. Street 109 Remembering John Steinbeck Adrian H. Goldstone 129 Book Collecting and Steinbeck BOOK REVIEWS Robert DeMott 136 Nelson Valjean. -

WHAT IS a FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, and PRODUCING LANDSCAPES in ST ELIZABETH, JAMAICA by Gary R. Schnakenberg a DISSERTATION

WHAT IS A FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, AND PRODUCING LANDSCAPES IN ST ELIZABETH, JAMAICA By Gary R. Schnakenberg A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Geography – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT WHAT IS A FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, AND PRODUCING LANDSCAPES IN ST. ELIZABETH, JAMAICA By Gary R. Schnakenberg This dissertation research examined the operation of discourses associated with contemporary globalization in producing the agricultural landscape of an area of rural Jamaica. Subject to European colonial domination from the time of Columbus until the 1960s and then as a small island state in an unevenly globalizing world, Jamaica has long been subject to operations of unequal power relationships. Its history as a sugar colony based upon chattel slavery shaped aspects of the society that emerged, and left imprints on the ethnic makeup of the population, orientation of its economy, and beliefs, values, and attitudes of Jamaican people. Many of these are smallholder agriculturalists, a livelihood strategy common in former colonial places. Often ideas, notions, and practices about how farms and farming ‘ought-to-be’ in such places results from the operations and workings of discourse. As advanced by Foucault, ‘discourse’ refers to meanings and knowledge circulated among people and results in practices that in turn produce and re-produce those meanings and knowledge. Discourses define what is right, correct, can be known, and produce ‘the world as it is.’ They also have material effects, in that what it means ‘to farm’ results in a landscape that emerges from those meanings. In Jamaica, meanings of ‘farms’ and ‘farming’ have been shaped by discursive elements of contemporary globalization such as modernity, competition, and individualism. -

Draft Environmental Profile on Barbados

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE ON BARBADOS lunded by A. I.D., uruvau oF ;:it,!Iu(, anlibT'IechW)1 c(q,/, Office of Forestry, Environment and Natural Resources under PSSA SA/TOA 1-77 w it h U. rl1. an,] ri tln. Bi().;l)}lw o ProIr am iAY I 1 2 Pre[ared by: Fred Baumani May 1982 THE UNITED STATES NAI _C MMITEF RtMANANDTHEBIOSPHERE NATIO\~ ~Departmelnt of Stte I/C 02 IV Lem) WASHIN TO/l0.Cs02 An Introductory Note on Draft Environmental Profiles: The attached draft environmental report has been prepared under a contract between the U.S. Agency for Internationa] Development (AID), Bureau of Science and Technology (ST/FNR) and the U.S. Man and tile Bio sphere (MAB) Program. It is a proirninary review of information avail abl.e in the United St.:ites on the status of the environment and the natural resources of tile identi fled country and is one of a series of similar studies now underway on countries whtch receive U.S. bil.ateral assistance. This report Is the first step in a vprocess to develon better In formition for the A.i.). Miss ion: for hot counrry officials: and others on the enyI ronImenta1 s I I uat o n speri fi c count ri Ps and beginus to identify the most crit i-al areas of conccrn. A more comprehensive study may be undertaken in each country b Bei onal Bure;ls and/or A.I.D. Missions. These would involve Incal scicntists in a more detailed examin.ation of the actual sit uat ions as wel1 as a bet ter definition of issues, problems and priorities. -

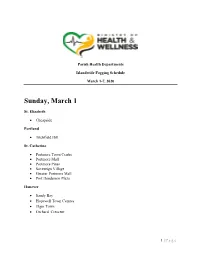

Islandwide Fogging Schedule

Parish Health Departments Islandwide Fogging Schedule March 1-7, 2020 Sunday, March 1 St. Elizabeth Cheapside Portland Titchfield Hill St. Catherine Portmore Town Centre Portmore Mall Portmore Pines Sovereign Village Greater Portmore Mall Port Henderson Plaza Hanover Sandy Bay Hopewell Town Centres Elgin Town Orchard Crescent 1 | P a g e Clarendon Pleasant Valley Woodside St. James Freeport Bickersteth Kingston & St. Andrew Norbrook Cherry Gardens Allerdyce Riva Ridge Jack’s Hill Road St. Thomas Johnstown Monday, March 2 St. Mary Castleton Baileys Vale Cromwelland Mile Gully Portland Hector River St. Ann St. Ann’s Bay Town area (Main Street, Wharf Street, Harbour Street, Jail Lane, Park Avenue) St. Ann’s Bay Regional Hospital Williams Field 2 | P a g e Manchester Banana Ground Top Bellefield & Schools Craighead Green Pond Bushy Park Highgate Knockpatrick Hanover Elgin Town Orchard Crescent Westmoreland New Works Trelawny Duanvale Freemans Hall St. James Freeport Bickersteth Clarendon May Pen Area (Town Centre) Hopefield/ Ommi Mews St. Elizabeth Castleton Pheonix Park Mount Pleasant St. Catherine Waterford Newland Washington Mews 3 | P a g e St. Thomas Johnstown Kingston & St. Andrew Standpipe Barbican Jack’s Hill Hope Pastures Mona Heights Tuesday, March 3 Hanover Mt. Peto Westmoreland New Roads Trelawny Duanvale Rock Spring St. James Freeport Cambridge St. Catherine Deeside Mickleton Meadows Venecia St. Ann Forrest Claremont Town Centre & Market 4 | P a g e Manchester Top Bellefield & Schools Freedom Downcaster Pike & Schools Plowden Naprieston Providence Content & Schools Wint Road & Environs St. Elizabeth Marborough Oxford Lalor Kingston & St. Andrew Roving NMIA Port Royal Mona Common Tavern Elletson Flats Clarendon Lionel Town Alley Gayle Alley Downer Portland Long Road St. -

Jamaica – European Union ACP Partnership

Jamaica – European Union ACP Partnership Annual Report 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................................................. 3 2. NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY .............................................................................. 6 2.1 ECONOMIC POLICY ............................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 SOCIAL POLICY AND POVERTY ALLEVIATION................................................................................... 7 2.3 RURAL DEVELOPMENT POLICY/FOOD SECURITY .............................................................................. 7 2.4 TRANSPORT/CONSTRUCTION POLICY ................................................................................................. 8 2.5 GOVERNANCE ..................................................................................................................................... 8 2.6 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT/CROSSCUTTING POLICIES .................................................................. 8 3. UPDATE ON THE SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SITUATION........................ 9 3.1 SOCIAL SITUATION ............................................................................................................................. 9 3.2 POLITICAL SITUATION ...................................................................................................................... 10 3.3 ECONOMIC SITUATION..................................................................................................................... -

INFANT MORTALITY RATE in THREE PARISHES of UESTERN Jatiaica, 1980 by * P Desai, BA * B F Hlanna, Bsc * B F Melville, Bsc

INFANT MORTALITY RATE IN THREE PARISHES OF UESTERN JAtiAICA, 1980 by * P Desai, BA * B F Hlanna, BSc * B F Melville, BSc **B A Wint, MB,BS, Dip PH *Department of Soc':ll & Preventive Medicine, University of the V'est Indies. I-Iona **Cornwall Ccunty 1le!a.th Adninistration, Ministry of Health, Jamaicn Report subroitted by the Department of Social & Preventive Medicine (1982) to: Unitud States Agency for International Development, and Ninirtry ofl*elth, Jamaica. USAID Project 11o. 42-0040, Contraict Nu. 532-7,-12 "Health Inprovcrmcnt for Youn , Cliildrcn in Cornwnll County, Jamaica". ABSTR \C The infant mortality rate is a sensitive index of health. However, in recent years, perhas due to und.er-reqistration of deaths, the infant -,nrtality rates of Jamaica, and particularly of certain parishes, have been so low as to mike thir reliability questionable. ThiV3 study souTht to establish the infant mortality rates for the narishes of St. Jamos, ilanowr and Trelawny dufing 19&0. Information on infant deaths in 1.9-0 was sought from a variety of sources, as was information on live births in the same year. Fewer than half of all infant deaths appeared to have been registered in 19C{O in the parishes studiud. The infant mortality rate for .90 was 27 per thousand liv births for these three narishes combined. The apparent under-reristration of infant deaths is discussed. ABBRFVIATIONS The followinq abbreviations have been used: IMR Infant Mortality 1'atc CHA - Community fei.ith ;ide PHN - Uublic Health Nurse (includinc, Senior Public Health Nurse) PHI - !,uhlic Health [ns ctor (including Chief Public Health Inspector) - Reistrar-Genri or RPa:'itrar-General s Department IZBE -- Peqi.strar I,;Pirt-L" anW Deaths 1 CI -. -

History of Portland

History of Portland The Parish of Portland is located at the north eastern tip of Jamaica and is to the north of St. Thomas and to the east of St. Mary. Portland is approximately 814 square kilometres and apart from the beautiful scenery which Portland boasts, the parish also comprises mountains that are a huge fortress, rugged, steep, and densely forested. Port Antonio and town of Titchfield. (Portland) The Blue Mountain range, Jamaica highest mountain falls in this parish. What we know today as the parish of Portland is the amalgamation of the parishes of St. George and a portion of St. Thomas. Portland has a very intriguing history. The original parish of Portland was created in 1723 by order of the then Governor, Duke of Portland, and also named in his honour. Port Antonio Port Antonio, the capital of Portland is considered a very old name and has been rendered numerous times. On an early map by the Spaniards, it is referred to as Pto de Anton, while a later one refers to Puerto de San Antonio. As early as 1582, the Abot Francisco, Marquis de Villa Lobos, mentions it in a letter to Phillip II. It was, however, not until 1685 that the name, Port Antonio was mentioned. Earlier on Portland was not always as large as it is today. When the parish was formed in 1723, it did not include the Buff Bay area, which was then part of St. George. Long Bay or Manchioneal were also not included. For many years there were disagreements between St. -

Pastoral Sketches

Class Book l'ki:si.\ri;i) my 39^ PASTORAL SKETCHES REV. B. CARRADINE, D.D. Author of "A Journey to Palestine," "Sanctification," "The Sec- ond Blessing in Symbol," "The Lottery Exposed," "Church Entertainments," "The Bottle," "Secret Societies," "The Better IVay," and "The Old Man." FIFTH EDITION CHRISTIAN WITNESS CO. CHICAGO, ILL. ^ <> Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1896, By Kentucky Methodist Publishing Co., In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. PREFACE. This book was undertaken with a view to mental rest and relaxation. The author had not the time nor means to go to the mountains or seashore for u season of recuperation, and so wrote this volume. Three of the chapters— viii., xviii., and xix. —were penned some years ago. The remainder of the book was written during a part of the spring and summer of the present year. As the author wrote, his eyes were often wet with tears, and frequently the smiles would play about the mouth over the facts and fancies that (lowed from his pen. But it was not limph to elicit -miles and tears from himself or others that lume was written. These are on!\ means to an end or, more truly speaking, the gilt on the sword or the paint and trimmings of the chariot. The reader cannot but see thai, under the pathos and hu- mor of the book, follies are punctured, formality assailed, sin d, truth exalted, and dee]) spiritual Ie860n8 inculcated. The book is a transcript of human character, a description of a part of the life procession that is -cni moving in the ec- ical world or that is beheld from the (."lunch In the ministerial e So the volume wa i for a purpose; not simply that (3) ' 4 PASTORAL SKETCHES. -

Combatting Corruption and Strengthening Integrity in Jamaica

!Loy to provide media stats.txt Cooperative Agreement: Combatting Corruption and Strengthening Integrity In Jamaica Award Number: AID-532-A-16-00001 Final Performance Report This report was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development, Jamaica. NIA – Combatting Corruption and Strengthening Integrity in Jamaica 2016-2020 National Integrity Action Cooperative Agreement – Combatting Corruption & Strengthening Integrity in Jamaica (CCSIJ) Final Performance Report – For Submission to the Development Experience Clearinghouse Submitted to: Kenneth Williams, Program Management Specialist Democracy and Governance USAID/Jamaica 142 Old Hope Road Kingston 6 Prepared by: Professor Trevor Munroe C.D and Marlon G. Moore, with the support of the entire staff National Integrity Action PO Box 112 Kingston 7 August 2020 COVER PHOTO: Prof. Munroe greets Deputy Director General of MOCA, Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) Millicent Sproul while newly appointed Director of the Financial Investigations Division (FID) Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) Selwyn Hay looks on. In the background are other NIA partners and stakeholders such as Minister of Justice Delroy Chuck; Mr. Luca Lo Conte of the European Union; Mr. Lloyd Distant of the Private Sector Organisation of Jamaica (PSOJ) and Mr. Oral Shaw of CVSS. DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CCSIJ Final Performance Report P a g e 2 of2 0 6 NIA – Combatting Corruption and Strengthening Integrity in Jamaica 2016-2020 Table of Contents Acronyms -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1. Introduction – Basic Cooperative Agreement Information ----------------------------------------- 5 2. Expenditure & Cost Share ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 3.