Report on Stockhausen's 'Carre' - Part 1 Edition (With Some Delay)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

About Half Way Through Proust

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2007). “The Best Form of Government…”: Cage’s Laissez-Faire Anarchism and Capitalism. The Open Space Magazine(8/9), pp. 91-115. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/5420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] “THE BEST FORM OF GOVERNMENT….”: CAGE’S LAISSEZ-FAIRE ANARCHISM AND CAPITALISM For Paul Obermayer, comrade and friend This article is an expanded version of a paper I gave at the conference ‘Hung up on the Number 64’ at the University of Huddersfield on 4th February 2006. My thanks to Gordon Downie, Richard Emsley, Harry Gilonis, Wieland Hoban, Martin Iddon, Paul Obermayer, Mic Spencer, Arnold Whittall and the editors of this journal for reading through the paper and subsequent article and giving many helpful comments. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

The Sublime As Model: Formal Complexity in Joyce, Eisenstein

The Sublime as Model: Formal Complexity in Joyce, Eisenstein and Stockhausen MARTIN S. WATSON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACUTLY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO ©Martin S. Watson 2016 Abstract: “The Sublime as Model: Formal Complexity in Joyce, Eisenstein and Stockhausen,” undertakes an investigation of three paradigmatic late-modernist works in three mediums — James Joyce’s novel, Finnegans Wake, Sergei Eisenstein’s film, Ivan the Terrible I & II, and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s orchestral work, Gruppen for Three Orchestras — with an aim to demonstrating cross-media similarities, and establishing a model for examining their most salient trait: formal complexity. This model is based on a reading of the Kantian “mathematical sublime” as found in his Critique of the Power of Judgment, as well as borrowing vocabulary from phenomenology, particularly that of Edmund Husserl. After establishing a critical vocabulary based around an analysis of the mathematical sublime and a survey of the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger, the dissertation investigates each of the three works and many of their attendant critical works with an aim to illuminate the ways in which their formal complexity can be described, how this type of complexity is particular to late-modernism in general, and these works in particular, and what conclusions can be drawn about the structure and meaning of the works and the critical analyses they accrue. Much of this analysis fits into the rubric of the meta- critical, and there is a strong focus on critical surveys, as the dissertation attempts to provide cross-media models for critical vocabulary, and drawing many examples from extant criticism. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media. -

The Compositions of György Ligeti in the 1950S and 1960S

118 Notes, September 2019 (along with their adaption in the twen- He fathers-forth whose beauty is pást tieth century), and ethnomusicologists change: exploring how the gamelan was em- Praíse hím. braced in North America, along with (Hopkins, “Pied Beauty,” stanza 2) other related cultural hybrids, can prof- John MacInnis itably reference this book. Dordt College This is a comprehensive life-and- works biography that belongs in acade- Metamorphosis in Music: The mic libraries. It is not hagiography. The Compositions of György Ligeti in the reader learns of Harrison’s destructive 1950s and 1960s. By Benjamin R. Levy. temper, his unhappy and unstable years Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. in New York, and how he sometimes [x, 292 p. ISBN 9780199381999 (hard- emotionally manipulated those who cover), $74; ISBN 9780199392019 loved him. Alves and Campbell recount (Oxford Scholarly Online), ISBN that Harrison’s outstanding regret was 9780199392002 (updf), ISBN how he treated people, and they share 9780190857394 (e-book), prices vary.] both the ups and downs of his life. Illustrations, music examples, bibliog- A reader of this book will note raphy, index. Harrison’s boldness in investing him- self completely in the art that inter- Long a devotee of György Ligeti’s ested him, without preoccupation with compositional theories, aesthetics, and a career trajectory or getting ahead. His practices, Benjamin Levy has published willingness to engage fully with ideas a book that tells the story of the com- off the beaten path made him a catalyst poser’s development up to about 1970. in the development of twentieth- What makes Levy’s efforts stand out is century American music. -

The Musical Legacy of Karlhein Stockhausen

06_907-140_BkRevs_pp246-287 11/8/17 11:10 AM Page 281 Book Reviews 281 to the composer’s conception of the piece, intended final chapter (“Conclusion: since it is a “diachronic narrative” of Nativity Between Surrealism and Scripture”), which events (ibid.). Conversely, Messiaen’s Vingt is unfortunate because it would have been regards centers on the birth of the eternal highly welcome, given this book’s fascinat- God in time. His “regards” are synchronic in ing viewpoints. nature—a jubilant, “‘timeless’ succession of In spite of the high quality of its insights, stills” (ibid.)—rather than a linear unfold- this book contains unfortunate content and ing of Nativity events. To grasp the compo- copy-editing errors. For example, in his dis- sitional aesthetics of Vingt regards more cussion of Harawi (p. 182), Burton reverses thoroughly, Burton turns to the Catholic the medieval color symbolism that writer Columba Marmion, whose view of Messiaen associated with violet in a 1967 the Nativity is truly more Catholic than that conversation with Claude Samuel (Conver - of Toesca. But Burton notes how much sa tions with Olivier Messiaen, trans. Felix Messiaen added to Marmion’s reading of Aprahamian [London: Stainer and Bell, the Nativity in the latter’s Le Christ dans ses 1976], 20) by stating that reddish violet mystères, while retaining his essential visual (purple) suggests the “Truth of Love” and “gazes” (p. 95). Respecting Trois petites litur- bluish violet (hyacinth) the “Love of gies, Burton probes the depths of the inven- Truth.” Although Burton repeats an error tive collage citation technique characteriz- in the source he cites (Audrey Ekdahl ing its texts, as Messiaen juxtaposes Davidson, Olivier Messiaen and the Tristan different images and phrases from the Myth [Westport, CR: Greenwood, 2001], Bible—interspersed with his own images— 25), this state of affairs reflects the Burton’s to generate a metaphorical rainbow of tendency to depend too much on secondary Scriptural associations (p. -

International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 18 | 2014 IAA Y Earbook

International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 18 | 2014 IAA Yearbook edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska The 18th volume of the International Yearbook of Aesthet- ics comprises a selection of papers presented at the 19th International Congress of Aesthetics, which took place edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska in Cracow in 2013. The Congress entitled “Aesthetics in Action” was in- tended to cover an extended research area of aesthet- ics going beyond the fine arts towards various forms of human practice. In this way it bore witness to the transformation that aesthetics has been undergoing for a few decades at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska International Yearbook of Aesthetics 2014 Volume 18 | 2014 ISBN 978-83-65148-21-6 International Association for Aesthetics International Association for Aesthetics Association Internationale d'Esthetique Wydawnictwo LIBRON | www.libron.pl 9 788365148216 edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Aesthetics, Cracow 2013 International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 18 | 2014 International Association for Aesthetics Association Internationale d'Esthetique Cover design: Joanna Krzempek Layout: LIBRON Proofreading: Tim Hardy ISBN 978-83-65148-21-6 © Krystyna Wilkoszewska and Authors Publication financed by Institute of Philosophy of the Jagiellonian University Every efort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Table of contents Krystyna Wilkoszewska -

David Tudor in Darmstadt Amy C

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Santa Cruz] On: 22 November 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 923037288] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Music Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713455393 David Tudor in Darmstadt Amy C. Beal To cite this Article Beal, Amy C.(2007) 'David Tudor in Darmstadt', Contemporary Music Review, 26: 1, 77 — 88 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/07494460601069242 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494460601069242 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Contemporary Music Review Vol. 26, No. 1, February 2007, pp. 77 – 88 David Tudor in Darmstadt1 Amy C. -

The Use of Visual Scores in Live Audiovisual Performance Ana Carvalho CIAC / CELCC – ISMAI, Portugal

The use of visual scores in Live Audiovisual Performance Ana Carvalho CIAC / CELCC – ISMAI, Portugal Abstract results to include improvisational and collaborative practices. The text will focus on the connection between moving image and music to what concerns the The graphic score at the intersection possibilities of presenting composition scores between sound and image as part of the creative process of live audiovisual performance in a way that The score is autonomous from the emphasizes its improvisation and collaborative performances, interpretations and variations it aspects. Scores are documents which preserve relates to. As an autonomous document, a the ephemeral quality of the event and score is not necessarily translated into a simultaneously makes possible its study and performance. To composer Cornelius Cardew, construction of its memory. How can score “written compositions are fired off into the composition convey the improvisation and future; even if never performed, the writing include the performer? Graphic scores in remains as a point of reference.” (Cardew composition for music has been doing that 1971). Also, scores cannot exist in place, or as since the 1950s through the work of several replacement, of a performance nor is a composers. We take as example the graphic translation of a performance into a document. score titled Treatise composed by Cornelius Graphic scores, as development from the Cardew. intermedia relationships established during the As we understand today, scores are resultant 1950s, from classical music scores, use visual from the interexchange between the arts. elements instead of musical symbols, to Scores, as representation of a composition to constitute a language that conveys instructions be performed, allow simultaneously organized to performers. -

Programme Notes

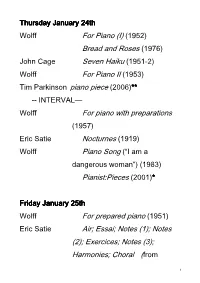

Thursday January 24th Wolff For Piano (I) (1952) Bread and Roses (1976) John Cage Seven Haiku (1951-2) Wolff For Piano II (1953) Tim Parkinson piano piece (2006)****** -- INTERVAL— Wolff For piano with preparations (1957) Eric Satie Nocturnes (1919) Wolff Piano Song (“I am a dangerous woman”) (1983) Pianist:Pieces (2001) *** Friday January 25th Wolff For prepared piano (1951) Eric Satie Air; Essai; Notes (1); Notes (2); Exercices; Notes (3); Harmonies; Choral (from 1 'Carnet d'esquisses et do croquis', 1900-13 ) Wolff A Piano Piece (2006) *** Charles Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) Steve Chase Piano Dances (2007-8) ****** Wolff Accompaniments (1972) --INTERVAL— Wolff Eight Days a Week Variation (1990) Cornelius Cardew Father Murphy (1973) Howard Skempton Whispers (2000) Wolff Preludes 1-11 (1980-1) Saturday January 26th Christopher Fox at the edge of time (2007) *** Wolff Studies (1974-6) Michael Parsons Oblique Pieces 8 and 9 (2007) ****** 2 Wolff Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida (1979) --INTERVAL-- Wolff Suite (I) (1954) For pianist (1959) Webern Variations (1936) Wolff Touch (2002) *** (** denotes world premiere; *** denotes UK premiere) for pianist: the piano music of Christian Wolff Given the importance within Christian Wolff’s compositional aesthetic of music which involves interaction between players, it is perhaps surprising that there is a significant body of works for solo instrument. In particular the piano proves to be central 3 to Wolff’s output, from the early 1950s to the present day. These concerts include no fewer than sixteen piano solos; I have chosen not to include a number of other works for indeterminate instrumentation which are well suited to the piano (the Tilbury pieces for example) as well as two recent anthologies of short pieces, A Keyboard Miscellany and Incidental Music , and also Long Piano (Peace March 11) of which I gave the European premiere in 2007. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Souster, Tim. 1977. ‘Intermodulation: A Short History’. Contact, 17. pp. 3-6. ISSN 0308-5066. ! [!] TIM SOUSTER 17 Intermodulation: A Short History ON THE EVENING of Saturday July 26, 1969, in a plastic geodesic dome on Tower Hill, a concert was given by four players who were subsequently to become the initial members of the live-electronics group Intermodulation: Andrew Powell (guitars, keyboards), Roger Smalley (keyboards, electronics), Tim Souster (viola, keyboards, electronics) and Robin Thompson (soprano sax, bassoon, keyboards and guitar). ( Andrew Powell was succeeded in 1970 by Peter Britton (percussion, electronics, key boards).) The concert was characterised by the rough and ready technology typical of electronic ventures at that time. Borrowed amplifiers failed to assert themselves. The dial of an ex-army sine-tone oscillator was nimbly controlled by Robin Thompson with his foot. A Hugh Davies-built ring-modulator nestled in its cardboard box on the floor. The 'visuals' (in the original version of my Triple Music I, written specially for this concert) consisted of coloured slides of food, footballers and political events, most of which failed to appear or did so upside-down. The whole occasion was dominated by a PA system lent and personally installed by Pete Townshend of The Who, who could be glimpsed lowering behind the loudspeaker columns throughout the show. Those lucky enough to be connected to this (for those days) mighty array of WEM equipment were able to play very loud indeed: I can remember little else. TECHNICAL PRE-CONDITIONS In 1968 Roger Smalley became composer-in-residence at King's College, Cambridge; I followed suit in 1969.