The Compositions of György Ligeti in the 1950S and 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

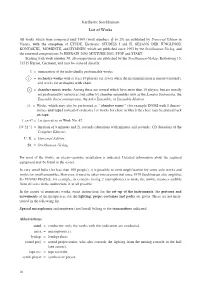

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

Department of Musicology, Faculty of Music, University of Arts in Belgrade Editors Prof. Dr. Tijana Popović Mladjenović Prof

Department of Musicology, Faculty of Music, University of Arts in Belgrade MUSICOLOGICAL STUDIES: MONOGRPAHS CONTEXTUALITY OF MUSICOLOGY – What, How, WHY AND Because Editors Prof. Dr. Tijana Popović Mladjenović Prof. Dr. Ana Stefanović Dr. Radoš Mitrović Prof. Dr. Vesna Mikić Reviewers Prof. Dr. Leon Stefanija Prof. Dr. Ivana Perković Prof. Dr. Branka Radović Proofreader Matthew James Whiffen Publisher Faculty of Music in Belgrade For Publisher Prof. Ljiljana Nestorovska, M.Mus. Dean of the Faculty of Music in Belgrade Editor-in-Chief Prof. Dr. Gordana Karan Executive Editor Marija Tomić Cover Design Dr. Ivana Petković Lozo ISBN 978-86-81340-25-7 This publication was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia. CONTEXTUALITY OF MUSICOLOGY What, How, Why and Because Editors Tijana Popović Mladjenović Ana Stefanović Radoš Mitrović Vesna Mikić UNIVERSITY OF ARTS IN BELGRADE FACULTY OF MUSIC Belgrade 2020 УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ УМЕТНОСТИ У БЕОГРАДУ ФАКУЛТЕТ МУЗИЧКЕ УМЕТНОСТИ UNIVERSITY OF ARTS IN BELGRADE FACULTY OF MUSIC Contents 7 Marija Maglov Musicology in the Context of Media – Media in the Context of Musicology ................................................... 279 Ivana Perković, Radmila Milinković, Ivana Petković Lozo Digital Music Collections in Serbian Libraries for New Music Research Initiatives .............................................. 293 IV What, How, Why and Because Nikola Komatović The Context(s) of Tonality/Tonalities ............................... 311 John Lam Chun-fai Stravinsky à Delage: (An)Hemitonic Pentatonicism as Japonisme ....... 319 Fabio Guilherme Poletto When Different Cultural Contexts Resize a Popular Song: A Study about The Girl from Ipanema .............................. 334 Ana Djordjević Music Between Layers – Music of Lepa sela lepo gore in The Context of Film Narrative ................................... -

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

About Half Way Through Proust

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2007). “The Best Form of Government…”: Cage’s Laissez-Faire Anarchism and Capitalism. The Open Space Magazine(8/9), pp. 91-115. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/5420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] “THE BEST FORM OF GOVERNMENT….”: CAGE’S LAISSEZ-FAIRE ANARCHISM AND CAPITALISM For Paul Obermayer, comrade and friend This article is an expanded version of a paper I gave at the conference ‘Hung up on the Number 64’ at the University of Huddersfield on 4th February 2006. My thanks to Gordon Downie, Richard Emsley, Harry Gilonis, Wieland Hoban, Martin Iddon, Paul Obermayer, Mic Spencer, Arnold Whittall and the editors of this journal for reading through the paper and subsequent article and giving many helpful comments. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

The Sublime As Model: Formal Complexity in Joyce, Eisenstein

The Sublime as Model: Formal Complexity in Joyce, Eisenstein and Stockhausen MARTIN S. WATSON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACUTLY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO ©Martin S. Watson 2016 Abstract: “The Sublime as Model: Formal Complexity in Joyce, Eisenstein and Stockhausen,” undertakes an investigation of three paradigmatic late-modernist works in three mediums — James Joyce’s novel, Finnegans Wake, Sergei Eisenstein’s film, Ivan the Terrible I & II, and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s orchestral work, Gruppen for Three Orchestras — with an aim to demonstrating cross-media similarities, and establishing a model for examining their most salient trait: formal complexity. This model is based on a reading of the Kantian “mathematical sublime” as found in his Critique of the Power of Judgment, as well as borrowing vocabulary from phenomenology, particularly that of Edmund Husserl. After establishing a critical vocabulary based around an analysis of the mathematical sublime and a survey of the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger, the dissertation investigates each of the three works and many of their attendant critical works with an aim to illuminate the ways in which their formal complexity can be described, how this type of complexity is particular to late-modernism in general, and these works in particular, and what conclusions can be drawn about the structure and meaning of the works and the critical analyses they accrue. Much of this analysis fits into the rubric of the meta- critical, and there is a strong focus on critical surveys, as the dissertation attempts to provide cross-media models for critical vocabulary, and drawing many examples from extant criticism. -

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Eamonn Bell All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Music studies’s turn to computation during the twentieth century has engendered particular habits of thought about music, habits that remain in operation long after the music scholar has stepped away from the computer. The computational attitude is a way of thinking about music that is learned at the computer but can be applied away from it. It may be manifest in actual computer use, or in invocations of computationalism, a theory of mind whose influence on twentieth-century music theory is palpable. It may also be manifest in more informal discussions about music, which make liberal use of computational metaphors. In Chapter 1, I describe this attitude, the stakes for considering the computer as one of its instruments, and the kinds of historical sources and methodologies we might draw on to chart its ascendance. The remainder of this dissertation considers distinct and varied cases from the mid-twentieth century in which computers or computationalist musical ideas were used to pursue new musical objects, to quantify and classify musical scores as data, and to instantiate a generally music-structuralist mode of analysis. I present an account of the decades-long effort to prepare an exhaustive and accurate catalog of the all-interval twelve-tone series (Chapter 2). This problem was first posed in the 1920s but was not solved until 1959, when the composer Hanns Jelinek collaborated with the computer engineer Heinz Zemanek to jointly develop and run a computer program. -

TEXTE Zur MUSIK Band 4 Werk-Einführungen Elektronische Musik Weltmusik Vorschläge Und Standpunkte Zum Werk Anderer

Inhalt TEXTE zur MUSIK Band 4 Werk-Einführungen Elektronische Musik Weltmusik Vorschläge und Standpunkte Zum Werk Anderer „Glauben Sie, daβ eine Gesellschaft ohne Wertvorstellungen leben kann?” „Was steht in TEXTE Band 4?” I Werk-Einführungen CHÖRE FÜR DORIS und CHORAl DREI LIEDER SONATINE KREUZSPIEL FORMEL SPIEL SCHLAGTRIO MOMENTE MIXTUR STOP HYMNEN mit Orchester Zur Uraufführung der Orchesterfassung Eine ‚amerikanische’ Aufführung im Freien PROZESSION AUS DEN SIEBEN TAGEN RICHTIGE DAUERN UNBEGRENZT VERBINDUNG TREFFPUNKT NACHTMUSIK ABWÄRTS OBEN UND UNTEN INTENSITÄT SETZ DIE SEGEL ZUR SONNE KOMMUNION ES Fragen und Antworten zur Intuitiven Musik GOLDSTAUB POLE und EXPO MANTRA FÜR KOMMENDE ZEITEN STERNKLANG 1 TRANS ALPHABET Am Himmel wandre ich... YLEM INORI Neues in INORI Vortrag über Hu Atmen gibt das Leben HERBSTMUSIK MUSIK IM BAUCH TIERKREIS Version für Kammerorchester HARLEKIN DER KLEINE HARLEKIN SIRIUS AMOUR JUBILÄUM IN FREUNDSCHAFT DER JAHRESLAUF II Elektronische Musik Vier Kriterien der Elektronischen Musik Fragen und Antworten zu den Vier Kriterien… Die Zukunft der elektroakustischen Apparaturen in der Musik III Weltmusik Erinnerungen an Japan Moderne Japanische Musik und Tradition Weltmusik IV Vorschläge und Standpunkte Interview I: Gespräch mit holländischem Kunstkreis Interview II: Zur Situation (Darmstädter Ferienkurse ΄74) Interview III: Denn alles ist Musik... Interview IV Die Musik und das Kind Du bist, was Du singst – Du wirst, was Du hörst – Vorschläge für die Zukunft des Orchesters Ein Briefwechsel ‚im Geiste der Zeit’ 2 Brief an den Deutschen Musikrat Briefwechsel über das Urheberrecht Silvester-Umfrage Fragen, die keine sind Finden Sie die Programmierung gut ? (Beethoven – Webern – Stockhausen) V Zum Werk Anderer Mahlers Biographie Niemand kann über seinen Schatten springen? Eine Buchbesprechung Über John Cage Zu Schönbergs 100. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen List of Works

Karlheinz Stockhausen List of Works All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are published by Universal Edition in Vienna, with the exception of ETUDE, Electronic STUDIES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE, KONTAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYMNEN, which are published since 1993 by the Stockhausen-Verlag, and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Starting with work number 30, all compositions are published by the Stockhausen-Verlag, Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany, and may be ordered directly. 1 = numeration of the individually performable works. r1 = orchestra works with at least 19 players (or fewer when the instrumentation is unconventional), and works for orchestra with choir. o1 = chamber music works. Among these are several which have more than 18 players, but are usually not performed by orchestras, but rather by chamber ensembles such as the London Sinfonietta, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, the Asko Ensemble, or Ensemble Modern. J35 = Works, which may also be performed as “chamber music” (for example INORI with 2 dancer- mimes and tape [instead of orchestra] or works for choir in which the choir may be played back on tape. 1. ex 47 = 1st derivative of Work No. 47. [9’21”] = duration of 9 minutes and 21 seconds (durations with minutes and seconds: CD durations of the Complete Edition). U. E. = Universal Edition. St. = Stockhausen-Verlag. For most of the works, an electro-acoustic installation is indicated. Detailed information about the required equipment may be found in the scores. In very small halls (for less than 100 people), it is possible to omit amplification for some solo works and works for small ensembles. -

Kreuzspiel, Louange À L'éternité De Jésus, and Mashups Three

Kreuzspiel, Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus, and Mashups Three Analytical Essays on Music from the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Thomas Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ©Copyright 2013 Thomas Johnson Johnson, Kreuzspiel, Louange, and Mashups TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1: Stockhausen’s Kreuzspiel and its Connection to his Oeuvre ….….….….….…........1 Chapter 2: Harmonic Development and The Theme of Eternity In Messiaen’s Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus …………………………………….....37 Chapter 3: Meaning and Structure in Mashups ………………………………………………….60 Appendix I: Mashups and Constituent Songs from the Text with Links ……………………....103 Appendix II: List of Ways Charles Ives Used Existing Musical Material ….….….….……...104 Appendix III: DJ Overdub’s “Five Step” with Constituent Samples ……………………….....105 Bibliography …………………………………........……...…………….…………………….106 i Johnson, Kreuzspiel, Louange, and Mashups LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE 1.1. Phase 1 pitched instruments ……………………………………………....………5 EXAMPLE 1.2. Phase 1 tom-toms …………………………………………………………………5 EXAMPLE 1.3. Registral rotation with linked pitches in measures 14-91 ………………………...6 EXAMPLE 1.4. Tumbas part from measures 7-9, with duration values above …………………....7 EXAMPLE 1.5. Phase 1 tumba series, measures 7-85 ……………………………………………..7 EXAMPLE 1.6. The serial treatment of the tom-toms in Phase 1 …………………………........…9 EXAMPLE 1.7. Phase two pitched mode ………………………………………………....……...11 EXAMPLE 1.8. Phase two percussion mode ………………………………………………....…..11 EXAMPLE 1.9. Pitched instruments section II …………………………………………………...13 EXAMPLE 1.10. Segmental grouping in pitched instruments in section II ………………….......14 EXAMPLE 1.11. -

Furchtlos Weiter: the Written Legacy of Stockhausen

Music & Letters,Vol.97No.2, ß The Author (2016). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/ml/gcw045, available online at www.ml.oxfordjournals.org Review-Article ‘FURCHTLOS WEITER’ : STOCKHAUSEN’S WRITTEN LEGACY Ã BY PAUL V. M ILLER Stockhausen thought big. In outdoor parks, underneath the earth in caverns, in heli- Downloaded from copters buzzing overhead, at La Scala, within a football stadium, a spherical auditor- ium, or a former factory, he sought out places in which his music would make a lasting impression on listeners. This was true until the end of his life: for his colossal Licht project (1977^2003), he fantasized about building seven opera houses, one for each opera. These dreams were part of a career that spanned nearly sixty years. His http://ml.oxfordjournals.org/ official catalogue contains 376 works in all. The Stockhausen Foundation’s CD edition now numbers over 100 items, a number that increases if one counts the so-called ‘Text-CDs’, which include audio recordings of many key lectures. Surely, few com- posers of the modern era have documented their careers as thoroughly. Central elements of Stockhausen’s thinking appear in Texte zur Musik, a series of seventeen volumes containing essays, sketches, interviews, correspondence, and miscel- lanea, published in instalments since 1963. The seven new volumes cover the years 1991^2007.1 Continuing the seven-year cycle of grouping material, the latest set spans by guest on August 26, 2016 two periods. Volumes 11^14 centre on the compositions written during 1991^8, and volumes 15^17 deal primarily with the composer’s activity from 1999 until his death in 2007.