Writing the Irish Past: an Investigation Into Post-Primary Irish History Textbook Emphases and Historiography, 1921–69’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

249 Nathalie Rougier and Iseult Honohan CHAPTER 10. Ireland

CHAPTER 10. IRELAND Nathalie Rougier and Iseult Honohan School of Politics and International Relations, University College Dublin Introduction Ireland’s peripheral position has historically often delayed the arrival of waves of social and cultural change in other parts of Europe. Part of its self-identity has derived from the narrative of its having been as a refuge for civilisation and Christianity during the invasions of what were once known as the ‘dark ages’, when it was described as ‘the island of saints and scholars’. Another part derives from its history of invasion, settlement and colonisation and, more specifically from its intimate relationship with Great Britain. The Republic of Ireland now occupies approximately five-sixths of the island of Ireland but from the Act of Union in 1800 until 1922, all of the island of Ireland was effectively part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ire- land. The war of Independence ended with the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, and on 6 December 1922 the entire island of Ireland became a self-governing British dominion called the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann). Northern Ire- land chose to opt out of the new dominion and rejoined the United King- dom on 8 December 1922. In 1937, a new constitution, the Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireann), replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State in the twenty-six county state, and called the state Ireland, or Éire in Irish. However, it was not until 1949, after the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, that the state was declared, officially, to be the Republic of Ireland (Garvin, 2005). -

A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969

ireiana Edward Norman I Edward Norman A History of Modem Ireland 1800-1969 Advisory Editor J. H. Plumb PENGUIN BOOKS 1971 Contents Preface to the Pelican Edition 7 1. Irish Questions and English Answers 9 2. The Union 29 3. O'Connell and Radicalism 53 4. Radicalism and Reform 76 5. The Genesis of Modern Irish Nationalism 108 6. Experiment and Rebellion 138 7. The Failure of the Tiberal Alliance 170 8. Parnellism 196 9. Consolidation and Dissent 221 10. The Revolution 254 11. The Divided Nation 289 Note on Further Reading 315 Index 323 Pelican Books A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969 Edward Norman is lecturer in modern British constitutional and ecclesiastical history at the University of Cambridge, Dean of Peterhouse, Cambridge, a Church of England clergyman and an assistant chaplain to a hospital. His publications include a book on religion in America and Canada, The Conscience of the State in North America, The Early Development of Irish Society, Anti-Catholicism in 'Victorian England and The Catholic Church and Ireland. Edward Norman also contributes articles on religious topics to the Spectator. Preface to the Pelican Edition This book is intended as an introduction to the political history of Ireland in modern times. It was commissioned - and most of it was actually written - before the present disturbances fell upon the country. It was unfortunate that its publication in 1971 coincided with a moment of extreme controversy, be¬ cause it was intended to provide a cool look at the unhappy divisions of Ireland. Instead of assuming the structure of interpretation imposed by writers soaked in Irish national feeling, or dependent upon them, the book tried to consider Ireland’s political development as a part of the general evolu¬ tion of British politics in the last two hundred years. -

Scotch-Irish"

HON. JOHN C. LINEHAN. THE IRISH SCOTS 'SCOTCH-IRISH" AN HISTORICAL AND ETHNOLOGICAL MONOGRAPH, WITH SOME REFERENCE TO SCOTIA MAJOR AND SCOTIA MINOR TO WHICH IS ADDED A CHAPTER ON "HOW THE IRISH CAME AS BUILDERS OF THE NATION' By Hon. JOHN C LINEHAN State Insurance Commissioner of New Hampshire. Member, the New Hampshire Historical Society. Treasurer-General, American-Irish Historical Society. Late Department Commander, New Hampshire, Grand Army of the Republic. Many Years a Director of the Gettysburg Battlefield Association. CONCORD, N. H. THE AMERICAN-IRISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY 190?,, , , ,,, A WORD AT THE START. This monograph on TJic Irish Scots and The " Scotch- Irish" was originally prepared by me for The Granite Monthly, of Concord, N. H. It was published in that magazine in three successiv'e instalments which appeared, respectively, in the issues of January, February and March, 1888. With the exception of a few minor changes, the monograph is now reproduced as originally written. The paper here presented on How the Irish Came as Builders of The Natioji is based on articles contributed by me to the Boston Pilot in 1 890, and at other periods, and on an article contributed by me to the Boston Sunday Globe oi March 17, 1895. The Supplementary Facts and Comment, forming the conclusion of this publication, will be found of special interest and value in connection with the preceding sections of the work. John C. Linehan. Concord, N. H., July i, 1902. THE IRISH SCOTS AND THE "SCOTCH- IRISH." A STUDY of peculiar interest to all of New Hampshire birth and origin is the early history of those people, who, differing from the settlers around them, were first called Irish by their English neighbors, "Scotch-Irish" by some of their descendants, and later on "Scotch" by writers like Mr. -

Republic of Ireland. Wikipedia. Last Modified

Republic of Ireland - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Republic of Ireland Permanent link From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page information Data item This article is about the modern state. For the revolutionary republic of 1919–1922, see Irish Cite this page Republic. For other uses, see Ireland (disambiguation). Print/export Ireland (/ˈaɪərlənd/ or /ˈɑrlənd/; Irish: Éire, Ireland[a] pronounced [ˈeː.ɾʲə] ( listen)), also known as the Republic Create a book Éire of Ireland (Irish: Poblacht na hÉireann), is a sovereign Download as PDF state in Europe occupying about five-sixths of the island Printable version of Ireland. The capital is Dublin, located in the eastern part of the island. The state shares its only land border Languages with Northern Ireland, one of the constituent countries of Acèh the United Kingdom. It is otherwise surrounded by the Адыгэбзэ Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south, Saint Flag Coat of arms George's Channel to the south east, and the Irish Sea to Afrikaans [10] Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann" Alemannisch the east. It is a unitary, parliamentary republic with an elected president serving as head of state. The head "The Soldiers' Song" Sorry, your browser either has JavaScript of government, the Taoiseach, is nominated by the lower Ænglisc disabled or does not have any supported house of parliament, Dáil Éireann. player. You can download the clip or download a Aragonés The modern Irish state gained effective independence player to play the clip in your browser. from the United Kingdom—as the Irish Free State—in Armãneashce 1922 following the Irish War of Independence, which Arpetan resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. -

Senates in Ireland from the Late Middle Ages to the Present

Precarious Bicameralism? Senates in Ireland from the late Middle Ages to the Present MacCarthaigh, M., & Martin, S. (2019). Precarious Bicameralism? Senates in Ireland from the late Middle Ages to the Present. In N. Bijleveld, C. Grittner, D. E. Smith, & W. Verstegen (Eds.), Reforming Senates: Upper Legislative Houses in North Atlantic Small Powers 1800-present (pp. 239-54). (Routledge Studies in Modern History). Routledge. Published in: Reforming Senates: Upper Legislative Houses in North Atlantic Small Powers 1800-present Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2019 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact -

A Brief History of Ireland

Reading Comprehension Name: ______________________________ Date: _____________________ A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRELAND Today, Ireland is a country with a bright future. In 2005, “Economist” magazine selected it as the best place in the world to live. Hundreds of thousands of people from all over the world share that opinion and have moved there in the last decade. But this optimistic outlook was not always the case. Ireland has a long, often bloody and tragic history. Ireland was first settled around the year 8000 BC, when hunter-gatherers came from Great Britain and Europe, possibly by land bridge. They lived by hunting and fishing for about four thousand years. Around 4000 BC they began to farm, and the old hunter-gatherer lifestyle gradually died out. The descendants of these original settlers built burial mounds and impressive monuments such as Ireland’s most famous prehistoric site, Newgrange. Newgrange is a stone tomb dated to sometime before 3000 BC: older than the pyramids in Egypt. Early Irish society was organized into a number of kingdoms, with a rich culture, a learned upper class, and artisans who created elaborate and beautiful metalwork with bronze, iron, and gold. Irish society was pagan for thousands of years. This changed in the early fifth century AD, when Christian missionaries, including the legendary St. Patrick, arrived. Christianity replaced the old pagan religions by the year 600. The early monks introduced the Roman alphabet to what had been largely an oral culture. They wrote down part of the rich collection of traditional stories, legends and mythology that might have otherwise been lost. -

MIXED CONTENT TALES in LEBOR NA HUIDRE Eric Patterson

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Theses Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Summer 2016 OLD AND NEW GODS IN AN AGE OF UNCERTAINTY: MIXED CONTENT TALES IN LEBOR NA HUIDRE Eric Patterson Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/masterstheses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Eric, "OLD AND NEW GODS IN AN AGE OF UNCERTAINTY: MIXED CONTENT TALES IN LEBOR NA HUIDRE" (2016). Masters Theses. 16. http://collected.jcu.edu/masterstheses/16 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OLD AND NEW GODS IN AN AGE OF UNCERTAINTY: MIXED CONTENT TALES IN LEBOR NA HUIDRE A Thesis Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts and Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Eric A. Patterson 2016 The thesis of Eric A. Patterson is hereby accepted: _________________________________________ ________________________ Reader – Paul V. Murphy Date _________________________________________ ________________________ Reader – Brenda Wirkus Date _________________________________________ ________________________ Advisor – Valerie McGowan-Doyle Date I certify that this is the original document _________________________________________ ________________________ Author – Eric A. Patterson Date No, not angelical, but of the old gods, Who wander about the world to waken the heart, The passionate, proud heart – that all the angels, Leaving nine heavens empty, would rock to sleep. - William Butler Yeats, The Countess Cathleen Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. -

THE IRISH EXPERIENCE of PARTITION John Coakley

Centre for International Borders Research Papers produced as part of the project Mapping frontiers, plotting pathways: routes to North-South cooperation in a divided island ETHNIC CONFLICT AND THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION: THE IRISH EXPERIENCE OF PARTITION John Coakley Project supported by the EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation and administered by the Higher Education Authority, 2004-06 ANCILLARY PAPER 3 ETHNIC CONFLICT AND THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION: THE IRISH EXPERIENCE OF PARTITION John Coakley MFPP Ancillary Papers No. 3, 2004 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 42) © the author, 2004 Mapping Frontiers, Plotting Pathways Ancillary Paper No. 3, 2004 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 42) Institute for British-Irish Studies Institute of Governance ISSN 1649-0304 Geary Institute for the Social Sciences Centre for International Borders Research University College Dublin Queen’s University Belfast ABSTRACT BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION ETHNIC CONFLICT AND THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION: John Coakley is an associate professor of politics at University College Dublin and THE IRISH EXPERIENCE OF PARTITION director of the Institute for British-Irish Studies. He has edited or co-edited Changing shades of orange and green: redefining the union and the nation in contemporary Ire- Although the partition of Ireland in 1921 was only one of several in which this strat- land (UCD Press, 2002); The territorial management of ethnic conflict (2nd ed., egy was adopted as Britain withdrew politically from territories formerly under its Frank Cass, 2003); From political violence to negotiated settlement: the winding path rule, it was marked by a number of distinctive features. This paper examines and to peace in twentieth century Ireland (UCD Press, 2004); and Politics in the Republic seeks to interpret some of these features. -

Phases-Of-Irish-History-By-Eoin-Macneill

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland m M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. 50 UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Boxmd in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &- Son, :: :: Ltd. :: :: 50 Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dublin 'First' 'E'diti.m 1919 Second Impression 1920 DA 5 30 3 ? CONTENTS PAGE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. - II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and fo *, Britain \ s -\ III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland . 61 IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian T t *> Ireland .... l 03 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 * VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 *n IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. 274 XI. The Norman Conquest . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 Index • 357 , FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. Their purpose is to correct and supple- ment. For the standpoint taken, no apology is necessary. Neither apathy nor antipathy can ever bring out the truth of history. I have been guilty of some inconsistency in my spelling of early Irish names, writing sometimes earlier, sometimes later forms. In the Index, I have endeavoured to remedy this defect. Since these chapters presume the reader's ac- quaintance with some general presentation of Irish history, they may be read, for the pre-Christian period, with Keating's account, for the Christian period, with any handbook of Irish history in print. -

Nationalism in Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, and Identity

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Nationalism In Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, And Identity Elaine Kirby Tolbert University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Tolbert, Elaine Kirby, "Nationalism In Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, And Identity" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 362. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/362 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism in Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, and Identity A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology The University of Mississippi by: Elaine Tolbert May 2013 Copyright Elaine Tolbert 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT A nation is defined by a collective identity that is constructed in part through interpretation of past places and events. In this paper, I examine the links between nationalism and archaeology and how the past is used in the construction of contemporary Irish national identity. In Ireland, national identity has been influenced by interpretation of ancient monuments, often combining the mythology and the archaeology of these sites. I focus on three celebrated monumental sites at Navan Fort, Newgrange, and the Hill of Tara, all of which play prominent roles in Irish mythology and have been extensively examined through archaeology. I examine both the mythology and the archaeology of these sites to determine the relationship between the two and to understand how this relationship between mythology and archaeology influences Irish identity. -

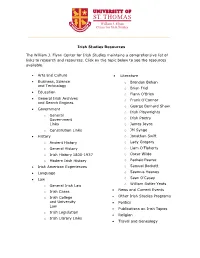

Irish Studies Resources

Irish Studies Resources The William J. Flynn Center for Irish Studies maintains a comprehensive list of links to research and resources. Click on the topic below to see the resources available. • Arts and Culture • Literature • Business, Science o Brendan Behan and Technology o Brian Friel • Education o Flann O’Brien • General Irish Archives o Frank O’Connor and Search Engines o George Bernard Shaw • Government o Irish Playwrights o General Government o Irish Poetry Links o James Joyce o Constitution Links o JM Synge • History o Jonathan Swift o Ancient History o Lady Gregory o General History o Liam O’Flaherty o Irish History 1800-1937 o Oscar Wilde o Modern Irish History o Padraic Pearse • Irish American Experiences o Samuel Beckett • Language o Seamus Heaney • Law o Sean O’Casey o William Butler Yeats o General Irish Law News and Current Events o Irish Cases • o Irish College • Other Irish Studies Programs and University • Politics Law • Publications on Irish Topics o Irish Legislation • Religion o Irish Library Links • Travel and Genealogy Irish Arts and Culture Art and Museums Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art Official Web site of the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art. Irish Heritage and Cultural Site Site with links to a variety of areas of Irish heritage, including parks, monuments, gardens, waterways and cultural institutions. National Gallery of Ireland Houses the national collection of Irish art as well as the collection of European master paintings. Music and Dance Celtic Music Archive Links to Ceolas, an online collection of information on Celtic music. Cork Opera House Web site for the Cork Opera House.