Incarcerated People and the Census

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Population Summary December 2020

Virginia Department of Corrections Monthly Population Summary December 2020 Research Unit Statistical Analysis & Forecast Unit www.vadoc.virginia.gov Virginia Department of Corrections Monthly Population Summary December 2020 Average Daily Population in DOC Institutions The average number of Virginia state responsible offenders incarcerated in DOC institutions in December 2020 was 24,185. This is a 2.01% decrease from the 24,681 average Virginia inmate population in custody last month and a 17.43% decrease from the average population (29,292) reported one year ago. In December 2020, the average number of out of state offenders housed in contract beds was 50. The total average institutional daily population (ADP) in DOC institutions was 24,235 offenders. Facility Type Total Facilities ADP Major Institution 26 21,324 Field Unit 8 833 Work Center 5 565 Private Prison 1 1,492 Secure Hospital Unit 2 21 Total 42 24,235 Community Corrections Caseload The end of month Probation & Parole caseload for December 2020 was 68,279 This is a 0.51% increase from the 67,935 reported for last month and a 1.97% decrease from the 69,651 offenders reported one year ago. Data Sources The Statistical Analysis and Forecast (SAF) Unit compiles the information contained in this Monthly Population Summary from various Corrections Technology Services Unit (CTSU) Institutional and Community Corrections reports and supplemental reports provided by Community Corrections. For additional information, contact the SAF Unit at 804-887-8236 or [email protected]. Virginia Department of Corrections Monthly Population Summary December 2020 Executive Summary Institutions ADP VADOC Major Institutions 21,324 VADOC Inmates 21,274 Out of State (OOS) Contract Inmates 50 Hawaii 2 U.S. -

VADOC Annual Report

Management Information Summary Annual Report For the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2018 Compiled by the Budget Office On the Cover Re-Entry Opportunities through Food Service Under the Food Services umbrella, offenders have many options for trainings to develop skills that will increase their employability, including participation in the Foundation for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management Program (Levels I and II), ServSafe Certification, and Cooks and Bakers Apprenticeship Program. Almost Home Café and New Beginnings Restaurant Almost Home Café and New Beginnings Restaurant are located at VADOC’s Headquarters in Richmond. The fully operational cafeteria and restaurant are staffed by female offenders who serve the building’s staff and visitors. The offender workers are securely transported from Central Virginia Correctional Unit and Chesterfield’s Women’s Detention and Diversion Center to Headquarters where they pro- vide breakfast and lunch services for purchase. The offenders in this Culinary Arts program participate in the ServSafe Safe Food Protection Manager Certification Program, as well as Foundations for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management (Levels I and II) through the National Restaurant Association. The program has is also expanded to include a full scale bakery (Fresh Start Bakery) and offers a Baker’s Apprenticeship through the Agency’s Department of Education. ServSafe Food Protection Manager Certification The ServSafe Program Certification is awarded by the National Restaurant Association. Since May 2011, the VADOC has certified more than 12,500 offenders throughout Virginia’s facilities. Foundations for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management Foundations for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management is taught at fourteen facilities. The Staff Dining Halls have been converted into Restaurants where offenders are taught Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management (Levels I and II). -

Appellant, V. H

PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT No. 18-7300 ALFONZA HARDY GREENHILL, Plaintiff - Appellant, v. HAROLD W. CLARKE, Director of the State of Virginia Department of Corrections; A. DAVID ROBINSON, Chief of Corrections Operations of the State of Virginia Department of Corrections; EARL BARKSDALE, Warden of Red Onion State Prison, Defendants - Appellees. ---------------------------------------------- DAN PACHOLKE, former corrections official; JEANNE WOODFORD, former corrections official; PHIL STANLEY, former corrections official; DICK MORGAN, former corrections official; ELDON VAIL, former corrections official; PROFESSORS AND PRACTITIONERS OF PSYCHIATRY, PSYCHOLOGY, AND MEDICINE; MUSLIM ADVOCATES; RECONSTRUCTIONIST RABBINCAL ASSOCIATION; INTERFAITH ALLIANCE FOUNDATION, Amici Supporting Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia, at Roanoke. James P. Jones, District Judge. (7:16-cv-00068-JPJ-RSB) Argued: October 31, 2019 Decided: December 6, 2019 Before NIEMEYER and AGEE, Circuit Judges, and Thomas S. KLEEH, United States District Judge for the Northern District of West Virginia, sitting by designation. Vacated and remanded with instructions by published opinion. Judge Niemeyer wrote the opinion, in which Judge Agee and Judge Kleeh joined. ARGUED: Daniel Mark Greenfield, NORTHWESTERN PRITZKER SCHOOL OF LAW, Chicago, Illinois, for Appellant. Toby Jay Heytens, OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, Richmond, Virginia, for Appellee. ON BRIEF: David M. Shapiro, Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center, NORTHWESTERN PRITZKER SCHOOL OF LAW, Chicago, Illinois, for Appellant. Mark R. Herring, Attorney General, Victoria N. Pearson, Deputy Attorney General, Laura H. Cahill, Assistant Attorney Counsel, Matthew R. McGuire, Principal Deputy Solicitor General, Michelle S. Kallen, Deputy Solicitor General, Brittany M. Jones, John Marshall Fellow, OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, Richmond, Virginia, for Appellee. -

Prison Calendars 042506 Sorted

PRISON NAME LOCATION CALENDAR Distance Augusta Correctional Center Staunton Staunton 17 Baskerville Correctional Unit Baskerville Lawrenceville 25 Beaumont Correctional Center Beaumont Richmond 26 Bland Correctional Center Bland Blacksburg 33 Botetourt Correctional Unit 2 Troutville Lynchburg 43 Brunswick Correctional Center Lawrenceville Lawrenceville 0 Buckingham Correctional Center Dilwyn Charlottesville 37 Caroline Correctional Center Hanover Richmond 20 Central Virginia Regional Jail Orange Charlottesville 25 Coffeewood Correctional Center Mitchells Charlottesville 33 Cold Springs Correctional Unit Greenville Staunton 9 Commonwealth of Virginia Richmond Richmond 2 Deep Meadow Correctional Center Capron Richmond 55 Deerfield Correctional Center Capron Richmond 55 Dilwyn Correctional Center Dilwyn Charlottesville 37 Dinwiddie Correctional Unit Church Road Richmond 23 Dinwiddie County Jail Dinwiddie Richmond 30 Fairfax Correctional Unit #3 Fairfax Fairfax 0 Fluvanna Correctional Center Troy Charlottesville 14 Greensville Correctional Center Jarratt Richmond 47 Halifax Correctional Unit Halifax Lynchburg 44 Hampton Roads Regional Jail Portsmouth Norfolk 7 Haynesville Correctional Center Haynesville Richmond 53 Henrico County Jail-East Barhamsville Richmond 36 Henrico County Regional Jail Richmond Richmond 5 Indian Creek Correctional Center Chesapeake Norfolk 10 James River Correctional Center State Farm Richmond 21 Keen Mountain Correctional Center Oakwood Wise 40 Lawrenceville Correctional Lawrenceville Lawrenceville 0 Loudon County -

RED ONION STATE PRISON Super-Maximum Security Confinement in Virginia

April 1999 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES RED ONION STATE PRISON Super-Maximum Security Confinement in Virginia The day I arrived I was...told that I was at Red Onion now and if I act up they would kill me and there was nothing anyone could or would do about it. Inmate Statement to Human Rights Watch I. SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................4 III. RED ONION STATE PRISON: BACKGROUND...................................................................5 IV. A DAY IN THE LIFE: BASIC CONDITIONS AT RED ONION ...........................................7 General Population ..............................................................................................................7 Segregation ..........................................................................................................................9 Mentally Ill Inmates...........................................................................................................10 V. ADMISSION AND RELEASE ................................................................................................11 VI. THE USE OF SEGREGATION .......................................................................................15 VII. STAFF-PRISONER RELATIONS ........................................................................................16 VIII. USE -

Pdfthorpe, Et Al V. Virginia Department of Corrections

Case 3:19-cv-00332 Document 1 Filed 05/06/19 Page 1 of 98 PageID# 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION WILLIAM THORPE, FREDERICK HAMMER, DMITRY KHAVKIN, GERALD MCNABB, GARY WALL, VERNON BROOKS, BRIAN CAVITT, DEREK CORNELISON, CHRISTOPHER COTTRELL, PETER MUKURIA, STEVEN RIDDICK, and KEVIN SNODGRASS, each individually and as representatives of a class of similarly situated persons, Plaintiffs, v. CASE NO. VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, HAROLD CLARKE, RANDALL C. MATHENA, H. SCOTT RICHESON, A. DAVID ROBINSON, HENRY J. PONTON, MARCUS ELAM, DENISE MALONE, STEVE HERRICK, TORI RAIFORD, JEFFREY KISER, and CARL MANIS, each individually and in their official capacities, Defendants. CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 1. Named Plaintiffs William Thorpe, Frederick Hammer, Dmitry Khavkin, Gerald McNabb, Gary Wall, Vernon Brooks, Brian Cavitt, Derek Cornelison, Christopher Cottrell, Peter Mukuria, Steven Riddick, and Kevin Snodgrass bring this action against the Virginia Department of Corrections (“VDOC”) and the individual defendants, on behalf of themselves and others similarly situated. These men have been isolated in solitary confinement at Virginia’s twin maximum-security prisons, Red Onion and Wallens Ridge State Prisons—and have remained in long-term solitary confinement for between two -1- Case 3:19-cv-00332 Document 1 Filed 05/06/19 Page 2 of 98 PageID# 2 and 23 years. No Virginia sentencing statute or regulation requires VDOC to place these men in long-term solitary confinement based on their crimes or sentences. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 2. As a result of their long-term solitary confinement, the Named Plaintiffs have suffered severe physical and mental health damage, including weight loss, auditory and visual hallucinations, emotional distress, Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder, severe sensory deprivation, and suicidal thoughts. -

Commonwealth of Virginia Department of Corrections Western Region Office 5427 Peters Creek Road Roanoke, Virginia 24019

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS WESTERN REGION OFFICE 5427 PETERS CREEK ROAD ROANOKE, VIRGINIA 24019 June 17, 2020 ADDENDUM NUMBER 1 TO ALL BIDDERS: Reference: DOCW-756-21-01 Commodity: 03145 Filters Air Conditioner/Furnace-Disposable Type Dated: June 17, 2020 For Delivery To: Western Region Institutions, Field Units, Detention/Diversion Centers Bid Due: July 1, 2020 The solicitation is hereby changed as follows: 1. Page 4 of 23, Section I, Purpose, changed to read: (denoted in yellow) The Commonwealth of Virginia, Department of Corrections Western Region invites qualified vendors to submit bids to provide Disposable HVAC Air Filters to the Western Region Facilities for the Department of Corrections on an as needed basis. Facilities include: Augusta Correctional Center, Bland Correctional Center, Green Rock Correctional Center, Keen Mountain Correctional Center, Marion Correctional Treatment Center, Patrick Henry Correctional Unit #28, Pocahontas State Correctional Center, River North Correctional Center, Red Onion State Prison, Wallens Ridge State Prison, Appalachian Community Corrections Alternative Program Facility, (ACCAP), Harrisonburg Community Corrections Alternative Program Facility, (HCCAP), Cold Springs Correctional Unit, and Wise Correctional Unit. The estimated annual filter usage across these facilities is approximately 5,300 individual filters. DOC Institution—Physical Ship to Addresses Augusta Correctional Center, 1821 Estaline Valley Road, Craigsville, VA 24430 Bland Correctional Center, 256 Bland Farm Road, Bland, VA 24315-4960 Green Rock Correctional Center, 475 Green Rock Lane, Chatham, VA 24531 Keen Mountain Correctional Center, 3402 Kennel Gap Road, Oakwood, VA 24631 Marion Correctional Treatment Center, 110 Wright Street, Marion, VA 24354-3145 Pocahontas Correctional Center, 317 Old Mountain Road, Pocahontas, VA 24635-0518 Red Onion State Prison, 10800 H. -

WESTERN Western Regional Office Tecora Johnson Some ? ? ? ? Bland Correctional Center Shakita Bland Approx 130 ? ? ?

DST TRAINING FIGURES FACILITY FACILITATOR NUMBER NUMBER EXEC TEAM Turnover LEAD TRAINED NOT TRAINED TRAINED WESTERN Western Regional Office Tecora Johnson Some ? ? ? ? Bland Correctional Center Shakita Bland Approx 130 ? ? ? Pocahontas State Correctional Gary Bowker 118 218 yes medium Center Augusta Correctional Center Kaye Bryant 15-20 ? Not unit head high Tecora Johnson Wise Correctional Unit Lafayette Fleming 32 2 yes low Marion Treatment Correctional Shakita Bland Approx 150 ? ? ? Center Keen Mountain Correctional Center Shakita Bland Approx 80 ? ? ? Wallens Ridge State Prison Shakita Bland 16 ? yes ? Patrick Henry Correctional Unit Donna Carter ? ? ? ? Green Rock Correctional Center Gary Bowker 144 147 yes medium Red Onion State Prison Lafayette Fleming 34 ? yes low Cold Springs Correctional Unit Gary Bowker 85 18 (Will be ? low Kaye Bryant trained by end July) District 12 - Staunton Kaye Bryant All 0 yes low Not unit head District 13 – Lynchburg Tecora Johnson All 0 ? medium District 14 – Danville Gary Bowker 25 25 (Will be ? low Donna Carter trained by end July) District 15 Roanoke Kaye Bryant 12-15 All will be no low/high trained by end July District 16 Wytheville Kaye Bryant 15-20 0 yes low Not unit head District 17 Abingdon Shakita Bland 24 0 yes ? District 18 Norton Lafayette Fleming ? 2 yes low District 20 - Bedford Tecora Johnson 0 10 ? ? District 22 – Martinsville Donna Carter All 0 yes ? District 28 – Radford Kaye Bryant ? All will be ? low trained by end July District 37 Rocky Mount Donna Carter All Poss 1 or 2 yes ? District -

19 Schedule A.Xlsx

Commonwealth of Virginia 2019 Federal Statewide Indirect Cost Allocation Plan Schedule A - 2019 Fixed Costs (Source: Carryforward Sch B) BUILDING BUILDING DGS DGS DGS USE USE M&O M&O RISK AGENCY MULTI SINGLE SINGLE MULTI MNGMNT 100 Senate (391,178) - - (17,186) 3 101 House of Delegates (756,213) - - (32,683) 3 103 Magistrate System - - - - 7 107 Division of Legislative Services (18,774) - - (4,514) 2 109 Division of Legislative Automated Systems (4,116) - - (1,353) - 110 Joint Legislative Audit/Review Commission (6,610) - - (1,589) - 111 Supreme Court 195,241 - - 15,430 (9) 112 Judicial Inquiry & Review Commission 4,319 - - 342 - 113 Circuit Courts - - - - 12 114 General District Courts - - - - 18 115 Juvenile & Domestic Relations District Courts - - - - 16 116 Combined District Courts - - - - 4 117 Virginia State Bar - - - - 3 119 Lt. Governor 20,774 - - 415 - 121 Office of the Governor 433,550 - - 32,862 2 123 Department of Military Affairs - - - - 114 125 Court of Appeals of Virginia 14,132 1,895 (60) 1,117 2 127 Department of Emergency Management - - - - 5 128 Virginia Veterans' Care Center - - - - - 132 Department of Elections 66,045 - - 989 - 140 Department of Criminal Justice Services 172,108 - - 2,576 1 141 Attorney General & Department of Law (417,000) - - (28,213) 9 142 Virginia State Crime Commission 13,742 - - 391 - 146 The Science Museum of Virginia - - - - 2 147 Office of the State Inspector General 32,411 - - 2,086 2 148 Virginia Commission for the Arts 42,484 - - 760 - 149 Administration of Health Insurance - - - - - 154 -

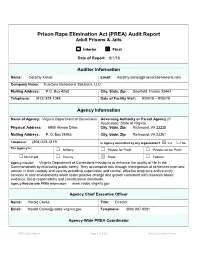

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Audit Report Adult Prisons & Jails

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Audit Report Adult Prisons & Jails ☐ Interim ☒ Final Date of Report 9/1/18 Auditor Information Name: Dorothy Xanos Email: [email protected] Company Name: TrueCore Behavioral Solutions, LLC Mailing Address: P.O. Box 4068 City, State, Zip: Deerfield, Florida 33442 Telephone: (813) 918-1088 Date of Facility Visit: 9/04/18 – 9/06/18 Agency Information Name of Agency: Virginia Department of Corrections Governing Authority or Parent Agency (If Applicable): State of Virginia Physical Address: 6900 Atmore Drive City, State, Zip: Richmond, VA 23225 Mailing Address: P. O. Box 26963 City, State, Zip: Richmond, VA 23261 Telephone: (804) 674-3119 Is Agency accredited by any organization? ☒ Yes ☐ No The Agency Is: ☐ Military ☐ Private for Profit ☐ Private not for Profit ☐ Municipal ☐ County ☒ State ☐ Federal Agency mission: Virginia Department of Corrections mission is to enhance the quality of life in the Commonwealth by improving public safety. They accomplish this through reintegration of sentenced men and women in their custody and care by providing supervision and control, effective programs and re-entry services in safe environments which foster positive change and growth consistent with research based evidence, fiscal responsibility and constitutional standards. Agency Website with PREA Information: www.vadoc.virginia.gov Agency Chief Executive Officer Name: Harold Clarke Title: Director Email: [email protected] Telephone: (804) 887-8081 Agency-Wide PREA Coordinator PREA Audit Report Page 1 of 108 Red Onion State Prison Name: Rose Durbin Title: PREA/ADA Supervisor Email: [email protected] Telephone: (804) 887-7921 PREA Coordinator Reports to: Maria Vargo Number of Compliance Managers who report to the PREA Coordinator 3 Regional PREA/ADA Analyst – 40 Compliance Managers report to PREA Analyst Facility Information Name of Facility: Red Onion State Prison Physical Address: 10800 H. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the WESTERN DISTRICT of VIRGINIA Big Stone Gap Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA Big Stone Gap Division TYQUINE R. LEE, by and through his ) guardian, TAKEISHA L. BROWN, ) ) Plaintiff, ) REPORT AND ) RECOMMENDATION v. ) Case No.: 2:20cv00006 ) VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ) CORRECTIONS, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) Plaintiff, Tyquine R. Lee, (“Lee”), is a Virginia Department of Corrections, (“VDOC”), inmate previously housed at Red Onion State Prison, (“Red Onion”), in Pound, Virginia, who sues through his mother and legal guardian, Takeisha L. Brown, (“Brown”).1 On behalf of Lee, Brown filed this civil rights action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 against the various VDOC officials and Red Onion employees and VDOC contract psychiatrist Dr. Everett McDuffie, (“Dr. McDuffie”), alleging that the defendants were deliberately indifferent to his medical and mental health needs, in violation of his Eighth Amendment rights and violated his equal protection and due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. (Docket Item No. 1) (“Complaint”). The Complaint also raises claims on Lee’s behalf under the Americans With Disabilities Act, (“ADA”), 42 U.S.C. §12102 et seq., Rehabilitation Act of 1973, (“Rehabilitation Act”), 29 U.S.C. § 794 et seq., and state law for medical malpractice and intentional infliction of emotional distress. 1 Brown was appointed as Lee’s legal guardian by a Virginia state court on February 1, 2019. -1- This case is before the court on the Rule 12 Motion To Dismiss filed on behalf of the VDOC and defendants Gary Adams, Henry Ponton, Denise Malone, Jeffrey Kiser, Earl Barksdale, Amee Duncan, Arvil Gallihar, Larry Collins, Walter Swiney, Michael Younce, Justin Kiser, Roy Sykes, James D. -

Quality of Health Care Services in Virginia Jails and Prisons, And

Quality of Health Care Services in Virginia Jails and Prisons, and Impact of Requiring Community Services Boards to Provide Mental Health Services in Jails – Final Report of 2-year Study September 18, 2018 Meeting Stephen Weiss Senior Health Policy Analyst Study Background • This is the final report of a two year study concerning health care services provided in jails and prisons based on resolutions that did not pass out of House Rules committee but were approved by the JCHC members at the May 23, 2017 Work Plan Meeting 1. HJR 616 by Delegate O’Bannon: A study of the quality of health care services in jails and prisons including: A review of: • Quality and oversight of the delivery of health care services • The process for the development and implementation of performance measures • Enforcement of contracts Development of recommendations for improving the quality of health care services 2. HJR 779 by Delegate Holcomb: A study of jails to determine: • Whether to require Community Services Boards to provide mental health services in jails • The impact of requiring Community Services Boards to provide mental health services in jails, including the costs and benefits 2 Legal Obligation to Provide Health Care to the Incarcerated By law VADOC and the local and regional jails are required to provide adequate health care to incarcerated offenders (U.S. Const. Amend. VIII; §53.1-32, and § 53.1-126 Code of Virginia). Virginia Code concerning the purchase of medicine by jails and regional jails (§ 53.1-126) states: “The sheriff or jail superintendent shall purchase at prices as low as reasonably possible all foodstuffs and other provisions used in the feeding of jail prisoners and such clothing and medicine as may be necessary.” Access to adequate health care, not quality health care, was defined by the United States Supreme Court beginning in 1976 (Estelle v.