Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

Mélodie French Art Song Recital; Wednesday, April 28, 2021

UCM Music Presents UCM Music Presents MÉLODIE FRENCH ART SONG RECITAL Dr. Stella D. Roden and Students MÉLODIE FRENCH ART SONG RECITAL Dr. Stella D. Roden and Students Hart Recital Hall Cynthia Groff, piano Hart Recital Hall Cynthia Groff, piano Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Denise Robinson, piano Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Denise Robinson, piano 7:00 p.m. 7:00 p.m. In consideration of the performers, other audience members, and the live recording of this concert, please In consideration of the performers, other audience members, and the live recording of this concert, please silence all devices before the performance. Parents are expected to be responsible for their children's behavior. silence all devices before the performance. Parents are expected to be responsible for their children's behavior. Le Charme Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Le Charme Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Lucas Henley, baritone Lucas Henley, baritone Les cygnes Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) Les cygnes Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) Anna Sanderson, soprano Anna Sanderson, soprano Lydia Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Lydia Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Alex Scharfenberg, tenor Alex Scharfenberg, tenor Ici-bas! Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Ici-bas! Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Gabrielle Moore, soprano Gabrielle Moore, soprano Fleur desséchée Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) Fleur desséchée Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) Janie Turner, soprano Janie Turner, soprano Le lever de la lune Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Le lever de la lune Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Nikolas Baumert, baritone Nikolas Baumert, baritone continued on reverse continued on reverse Become a Concert Insider! Text the word “concerts” to 660-248-0496 Become a Concert Insider! Text the word “concerts” to 660-248-0496 or visit ucmmusic.com to sign up for news about upcoming events. -

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Mountain Shepherd

Newsletter of the The Salem United Methodist Church — Wolfsville MMoouunnttaaiinn SShheepphheerrdd Volume 30 March 2012 Number 3 Worship, Fellowship, & Prayer Opportunities at Salem during Lent THEME FOR LENT: “A Journey to Hope” Salem United Methodist Church—Wolfsville IN DIFFICULT INSIDE TIMES WHAT DO YOU GRAB ONTO? Journey to hope Skating Party photos on pages 10 & 11. DISCOVER the HOPE to HANDLE EVERYTHING Missions . 2 Bee-lievers Food Sales . 3 Although the series began Feb 22, you may join us at any time. Bee-lievers Prayer Shawls . 3 Each message can make a difference in our lives right now. Attendance & Offerings . 4 Sticky Buns Sales . 4 JOIN US on THE JOURNEY. Invitations to Church . 4 Follow Christ to the cross this Lenten OPEN Calendar of Events . 5 season. Learn from Pastor Bob’s A NEW Old Sanctuary Photo . 5 teachings on... Who’s Doing What, When? . 6 DOOR It’s Your Day! . 6 Wed Feb 22 Risk (Ash Wednesday) See REAL LIFE SITUATIONS Inspirational Reading . 7 with fresh eyes... Recipe . 7 Sun Feb 26 Choosing our Traveling From Our Pastor . 8 Companions no matter your Women’s Valentine Breakfast 9 Sun Mar 4 Self-Esteem mile marker in life. Snow Tubing/Skating Party 10 Sun Mar 11 Work Easter Flowers Order Form 11 Sun Mar 18 Temptation Commit to attend each week. Heavenly Humor . 12 Sun Mar 25 Money Invite a friend. Encounter Christ. Amazing Bible Facts . 12 Sun Apr 1 Suffering (Palm Sunday) 2 March 2012 The Mountain Shepherd The 22001122 MISSION PROJECTS Mountain Shepherd Monthly Paid 2012 % of Published monthly by Salem United Minimum Jan Goal Goal Methodist Church – Wolfsville. -

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni Citation Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni. (2021). Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 04:39:03 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660266 ADAPTING PIANO MUSIC FOR BALLET: TCHAIKOVSKY’S CHILDREN’S ALBUM, OP. 39 by Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou ____________________________________ Copyright © Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou 2021 A DMA Critical Essay Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Creative Project and Lecture-Recital Committee, we certify that we have read the Critical Essay prepared by: titled: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ submission of the final copies of the essay to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this Critical Essay prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement. -

Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky

APRIL 2020 RACHMANINOFF AND TCHAIKOVSKY APRIL 17 – 19, 2020 MASTERWORKS #7: Two Russian composers, teacher and pupil, both legends in the world of classical music and revered by their countrymen, shared something else in common: periods of severe and crippling depression. Dr. Richard Kogan, a Juilliard-trained pianist, lonely 14-year old into despair.x He mourned the loss graduate of Harvard College and Medical School, of his mother for the rest of his life and called it the and a Clinical Professor of Psychology on the faculty most “crucial event” he’d ever experienced.xi With of the Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City, his mother’s death, a young Tchaikovsky became has concluded that a disproportionate number of the parent figure for his younger twin brothers, the great composers of classical music suffered from Anatoly and Modest.xii Despite the family’s wish that mental illness.i In his years as a student, Dr. Kogan Tchaikovsky have a career in the Ministry of Justice, pursued both music and pre-medical studies. His the young man was drawn to music. When the St. roommate at Harvard was famed cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Petersburg Conservatory opened its doors in 1862, and, with violinist Lynn Chang, they performed as a Tchaikovsky was among its first students.xiii From that trio.ii With a choice between music and medicine, point forward, his musical path was clear, and his Dr. Kogan chose medicine, but, in so doing, noted work as a composer earned him a teaching position the close relationship between the two fields.iii In at the Moscow Conservatory. -

Concert Program

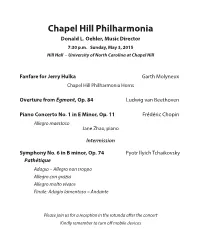

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

String Orchestra of Brooklyn Repertoire Updated February 28, 2011

String Orchestra of Brooklyn Repertoire Updated February 28, 2011 Anton Arensky Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky Johann Sebastian Bach Art of the Fugue, selections Piano Concerto No. 1 in d minor, BWV 1052 Piano Concerto No. 5 in f minor, BWV 1056 Erbarme Dich from St. Matthew's Passion Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 Samuel Barber Dover Beach for Baritone and Strings Adagio for Strings Bela Bartok Divertimento for Strings Roumanian Folk Dances Ludwig van Beethoven Egmont Overture* Grosse Fuge (arr. Furtwängler) Violin Concerto, Op. 61* Johannes Brahms Variations on a Theme by Haydn* Kenji Bunch Nocturne Tony Conrad Eleven Across John Corigliano Voyage for String Orchestra Claude Debussy Sacred and Profane Dances Antonin Dvorak Symphony No. 8* Josh Feltman Triptych Osvaldo Golijov Muertes des Angel Antonio Carlos Gomes Sonata for Strings Judd Greenstein Four on the Floor Edvard Grieg Holberg Suite Nathan Hall Last Rose Georg Frederic Handel Concerto Grosso Op. 6, No. 3 in D Major Ian Hartsough Stick Figures Bernard Herrmann Suite from Psycho Paul Hindemith Acht Stücke, Op. 43/3 Trauermusik for viola and strings Leos Janacek Suite for Strings Gabriel Lubell Quomodo sedet sola Gustav Mahler Adagietto from Symphony No. 5 Matt McBane 2 x 4 for String Octet Felix Mendelssohn Octet for Strings String Symphony No. 10 Symphony No. 1* Alex Mincek Ebb and Flow Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Adagio and Fugue, k546 Requiem Mass, k626* Serenata Notturna, k239 Sinfonia Concertante, k364* sull'aria from Le Nozze di Figaro* Symphony No. 40, k550* Arvo Pärt Fratres, version for String Orchestra and Percussion Krzysztof Penderecki Ciaconna (“Polish Requiem”) Josh Penman Lovesongs to God, second movement Tristan Perich I am not without my eyes open Duane Pitre Suspended in Dreams Claudio Santoro Mini Concerto for String Orchestra Franz Schubert Death and the Maiden, second movement (arr. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.